The Enterprising Woman Who Built—and Lost, and Rebuilt—a Booming Empire During the Klondike Gold Rush

With flinty perseverance and a golden touch, Belinda Mulrooney earned an unlikely fortune in the frozen north and reshaped the Canadian frontier

:focal(855x566:856x567)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/63/87/6387eca4-6cdb-476f-9454-1372614a9e63/nov2024_i02_prologue.jpg)

Exhausted and hungry, the prospectors stumbled into Dawson City in the late summer of 1898 after a grueling journey—and found what must have seemed a mirage. Before them towered a three-story hotel, light streaming through the windows from cut-crystal chandeliers and gleaming off the brass and mahogany bar. Inside the Fair View Hotel, its diminutive proprietor, Belinda Mulrooney, proffered menus boasting oysters and steak.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/08/8c/088cfd8d-454e-43da-919e-9a6de512070f/nov2024_i05_prologue.jpg)

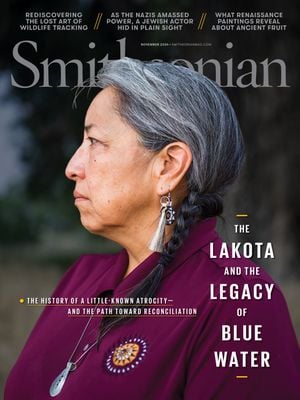

Mulrooney’s success, as a woman and an Irish immigrant with little education, was as improbable as the Fair View’s remote glamour. Only 26 when she opened the hotel in July of 1898, in two short years she’d come to be known as the richest woman in the Klondike, overseeing an empire that extended from hotels, restaurants and real estate development to mining companies, banks, even utilities. It’s a swashbuckling story, one marked by constant self-reinvention that saw Mulrooney help build a city, make and lose several fortunes, and leave a lasting legacy as a Yukon pioneer.

Yet Mulrooney’s legacy remains little known outside the frozen north. “I think she’s certainly up there with significant women who had an impact on Alaska, and she hasn’t been given the prominence that she deserves,” says Jo Antonson, executive director of the Alaska Historical Society. A true reckoning of Mulrooney’s life reveals her as a hero of the frontier—and perhaps its canniest business owner.

Born in 1872 in County Sligo, Ireland, Mulrooney stayed behind when her parents emigrated to America and spent her childhood on her maternal grandparents’ farm, surrounded by boys. That experience shaped her and inspired her legendary drive. “I never expected any favors,” Mulrooney told writer Helen Lyon Hawkins, who conducted a series of interviews in the late 1920s for a biography that was never published. “I knew a woman around men who couldn’t do her share is a nuisance and is left behind, so I tried to be in the front always, to lead.”

Thirteen when she finally joined her parents in the U.S., Mulrooney was unimpressed by life in the coal town of Archbald, Pennsylvania, and soon took a position as a nanny for a wealthy Philadelphia family. After the economic crash of 1891, Mulrooney took her savings to Chicago, sensing opportunity in the city’s preparations for the 1893 World’s Fair.

Mulrooney purchased a lot just outside the fair’s carnival strip and built on it, renting and then selling the property at considerable profit, which she used to buy a popular restaurant nearby. As the fair closed, Mulrooney learned that San Francisco was planning its own exposition and took her profits westward, where she repeated her real estate speculations. But when an 1895 fire in an uninsured building left her penniless, it was time to start over.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/36/de/36de95b2-992e-4782-8614-c7f7423f8b0d/nov2024_i11_prologue.jpg)

This time she found success in merchant ventures, bootlegging whiskey and other coveted supplies aboard the steamship City of Topeka between Seattle and southern Alaska—then reselling goods at frontier prices. She opened a store in Juneau and was scanning the landscape for opportunity when a prospector strolled into town, showing off some of the gold nuggets he’d found in what seemed like a promising strike in the Klondike. Instantly, Mulrooney began outfitting for an expedition that would change her life, and the frozen frontier, forever.

Getting to the Klondike gold fields in 1897 required astonishing mettle. The majority of stampeders, as new arrivals were known, came via a brutal overland trek, each explorer hauling gear by sled over the icy, 3,550-foot Chilkoot Pass. Mulrooney’s supplies required 30 such trips. Then came the two-week journey down the turbulent Yukon River to Dawson, for which travelers had to build their own boats.

Mulrooney landed in Dawson in April 1897, one of the first entrepreneurs on the scene. In an often-told anecdote, Mulrooney describes tossing her one remaining coin in the river for luck, announcing with breezy confidence: “I’ll start clean.”

But it wasn’t luck that made Belinda Mulrooney rich; it was her unerring ability to anticipate what people would most need. Her goods, including hot water bottles for miners enduring the frigid winter in tents, netted a 600 percent profit from that first trip. She also saw the miners were desperate for a good meal and opened an all-hours restaurant serving hearty homestyle fare.

Mulrooney’s eye for creative re-use proved key in an undeveloped environment where materials were scarce. “I started buying up all the boats and rafts that were arriving, hired a crew of young fellows who had nothing to do, and had them build cabins,” she said of her first Yukon real estate venture, which she embarked on shortly after arriving. Those cabins were soon selling for as much as $4,000 apiece, or more than $150,000 today.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4a/31/4a31d944-abc9-4b34-b3bc-ebcf432819f8/nov2024_i06_prologue.jpg)

Mulrooney also had a canny instinct for location. During that first Yukon spring, she scouted ground on which to open her first hotel and chose the junction of the two busiest gold-mining creeks, 16 miles outside of Dawson. The Grand Forks quickly became the miners’ primary gathering place and soon doubled as an official collection office for royalties demanded by the Canadian government. At night Mulrooney put the floor sweepings through a sluice, gleaning an extra $100 or so in gold dust daily. Perfectly positioned for intelligence-gathering, she invested accordingly and by the end of 1897 owned five gold claims—plus almost 20 percent of one of the region’s wealthiest mining companies.

Ever the expansionist, Mulrooney set out to build the finest hotel in Dawson City, one modeled on the elegant hotels she’d seen in Chicago and San Francisco. Calling it the Fair View, Mulrooney was meticulous in choosing the lace curtains, plush carpets, brass bedsteads and other finery that would make her new hotel the envy of the region’s other hoteliers, who housed most guests in rough dormitories. When explorer Mary E. Hitchcock arrived in Dawson in June 1898, she was deeply impressed and detailed her reaction in her 1899 memoir, Two Women in the Klondike: “The menu, beginning with ‘oyster cocktails,’ caused us to open our eyes wide with astonishment, after all that the papers have told us of the starvation about Dawson.”

The Fair View was the first property in town to have electricity. When miners bet Mulrooney $5,000 that she couldn’t keep the three-story building warm, she bought an old steamboat boiler, attaching a sawmill to provide the fuel. Mulrooney modernized the town in other ways, too, helping bring Dawson its first telephone and telegraph, housing the switchboard in the Fair View, and forming the Hygeia Water Supply Company to provide safe drinking water. It was less than two years since she arrived in Dawson, and already she was one of its foremost citizens.

“She really loomed large in the history of Dawson City,” says Angharad Wenz, director of the Dawson City Museum, adding that if we were to credit a single person with bringing the Klondike into the 20th century, Mulrooney would be the prime candidate.

As sharp-eyed as she was in business, Mulrooney proved less so in matters of the heart. Disaster came courting in the form of a sham European nobleman, “Count” Charles Eugene Carbonneau—actually a French Canadian barber from Montreal—whom Mulrooney wed in Dawson City on October 1, 1900.

Newspapers around the country published rhapsodic descriptions of the lavish wedding and followed the Carbonneaus on their honeymoon tour of Europe, running photographs of Mulrooney wearing furs and jewels in a mansion the couple rented in Nice. The next few years found the Carbonneaus wintering in Paris, in an apartment near the Champs-Élysées with a bevy of servants.

But Carbonneau’s profligate spending, dubious investments and mismanagement of Mulrooney’s mining companies emptied the couple’s bank accounts. Leaving the con man in France, where he was soon to be convicted of swindling and embezzlement, Mulrooney returned to Dawson alone in 1904.

Forced to start over yet again, she regathered her energies and in the spring of 1905 followed the next gold strike to Fairbanks, some 400 miles west of Dawson City, buying up claims in partnership with fellow investors. She also purchased several building lots and opened a bank in nearby Dome City. By the time Mulrooney filed for divorce from Carbonneau in July 1906, she was flush once again.

“She just did not give up, that woman,” says Melanie Mayer, author of the 2000 Mulrooney biography Staking Her Claim. “If she was down, well, she knew how she had gotten up before, and she went at it again from a different angle.”

Perhaps foreseeing the inevitable bust of the Alaskan claims, Mulrooney decamped to Washington State’s fertile Yakima Valley, where she ran a 20-acre farm and orchard, built an imposing stone castle, and reigned there into the 1920s. Locals came to refer to her as the Countess Carbonneau. But this attempt at a bucolic life didn’t prove profitable: She sold the acreage at a loss, leased the castle and moved to a modest cottage in Seattle, where she ended her career in humble fashion, de-rusting minesweepers in the shipyards during and after World War II. Though no longer commanding an empire, Mulrooney continued to prize her self-reliance and practical skill; in a photo taken in her 60s, she stands proudly in front of the seafaring equipment she maintained.

Still, it was her memories of the Klondike that Mulrooney most prized. Of her fondness for that wild country, she recalled poignantly: “I was young when I went there full of hope.” Later in life, Mulrooney took special pleasure in her membership in the male-only Yukon Order of Pioneers, which made an exception for her mining achievements and civic service.

In 1957, her money mostly gone, Mulrooney moved to a senior care facility in Seattle, where she died in 1967 at the age of 95. The obituary of the most daring self-made woman of the period read simply: “Born in Ireland, she came to Seattle in 1925. Mrs. Carbonneau was in the Klondike in 1898.” Her small footstone in the city’s Holyrood Cemetery bears only dates, and a name: B.A. Carbonneau.

Editors' note, November 4, 2024: A previous version of this article misstated the location of Fairbanks, Alaska; it is west of Dawson City. The article has been updated to correct this error.

Editors’ note, November 8, 2024: This article was updated with additional information from Melanie Mayer, co-author of the Mulrooney biography Staking Her Claim.