Escape From Boko Haram

In northern Nigeria, a fearless American educator has created a refuge for young women desperate to evade the terrorist group

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2b/14/2b14eae6-58cd-4d84-9934-6ab97350fef1/sep2015_c04_bokoharam_web-resize.jpg)

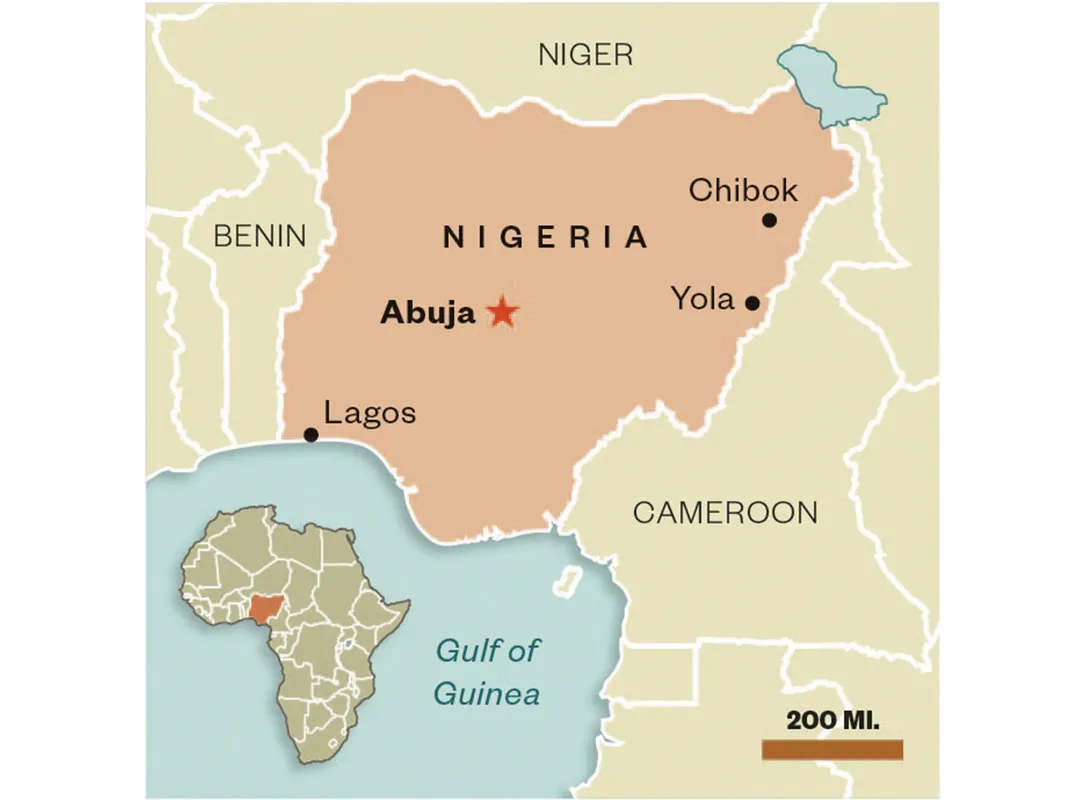

Shortly before six o’clock in the morning on August 30, 2014, Margee Ensign, president of the American University of Nigeria, met with her security chief in the large house that she occupies on campus, in Yola, near the nation’s eastern border, in Adamawa State. The news was bad. The chief, Lionel Rawlins, had gone to get the half-dozen security guards that Ensign was counting on to help her with a daring rescue mission, but the guards were asleep, or perhaps pretending to be, and couldn’t, or wouldn’t, be roused.

“They were afraid,” Rawlins later recalled.

Running a college doesn’t often entail making split-second decisions about daredevil forays into hostile territory, but as this Saturday dawned for the energetic five-foot California native with a doctorate in international political economy, it was gut-check time.

“The president looked at me and I looked at her, and I knew what she was thinking,” Rawlins said.

“We’re going,” Ensign said.

So they headed north in two Toyota vans, a suddenly meager contingent—Ensign, Rawlins, a driver and one other security guard—dashing down the crumbling two-lane highway through arid scrubland, deeper into remote country terrorized by the ruthless, heavily armed militant group called Boko Haram.

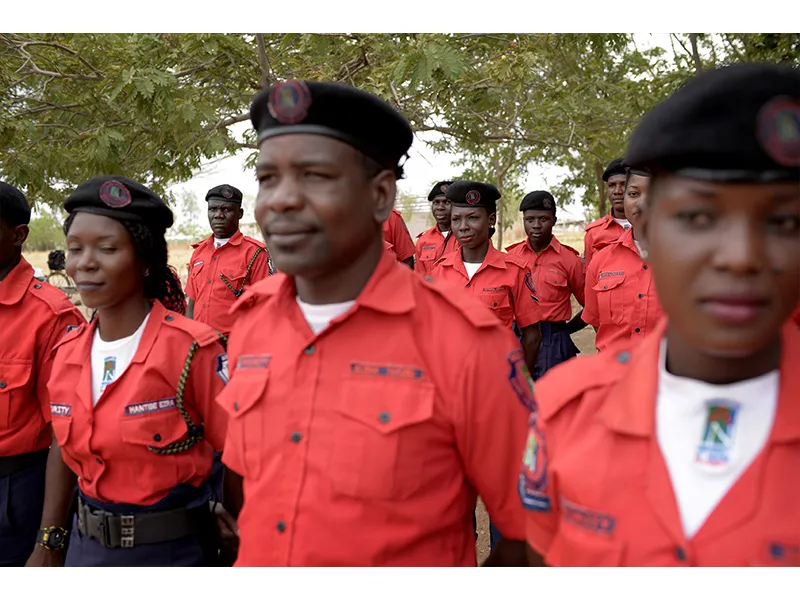

Rawlins, a former U.S. Marine, had contacts with vigilante groups in northern Nigeria, and thought he might be able to summon them if the going got tough. “All the way up there I’m playing war games in my mind,” he remembered.

After three tense hours on the road, expecting to be ambushed by terrorists wielding automatic rifles at any moment, the little convoy rounded a corner and Ensign saw 11 girls and their families and friends waving and yelling at the vehicles approaching in clouds of dust.

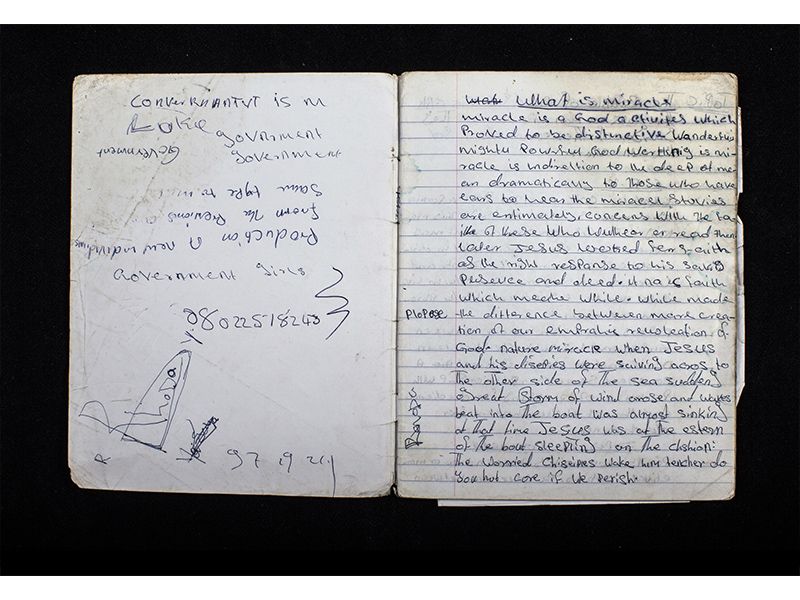

The girls had attended a boarding school near Chibok, an obscure provincial town that is now famous because of the attack on the school the previous April. The astonishing crime attracted attention worldwide, including the Twitter campaign #BringBackOurGirls.

On that nightmarish night of the April abduction, 57 of the 276 kidnapped girls were able to jump off the trucks that were spiriting them away, and flee into the bush. They eventually returned to their villages to spend the broiling summer with their families, fearing another kidnapping mission every night. One of those Chibok escapees had a sister at the American University of Nigeria, and it was she who approached Ensign in her campus office, pleading, “What can you do to help?”

Ensign resolved to bring some of the girls who’d escaped to the university, where they could live and complete their secondary schooling before beginning college coursework, all on full scholarship. The girls and their parents warmed to the idea, then risked everything to make the extraordinary roadside rendezvous from their scattered small villages in the bush with the university president herself—an unforgettable encounter. “They were so scared, so skinny,” Ensign said of the girls. “They had no money, no food, and they had all their possessions in little plastic bags.”

As the van engines kept running, Ensign leapt out, greeted the girls and their families and told them “with cool assurance” (Rawlins’ words) that all would be well. (“I didn’t get the fear gene,” Ensign later told me.) Quickly, about 200 locals gathered. Rawlins cast a wary glance at a group of men on the edge of the crowd whom nobody seemed to recognize. “We knew Boko Haram was in the area,” Rawlins said. He turned to Ensign and the others. “We’ve got ten minutes,” he told them. “Kiss everybody goodbye you want to kiss.” Then he began a countdown for the 22 people, girls and parents alike, who would go to Yola. “Five minutes. Three minutes. Two minutes. Get in the vans!”

**********

Long before she assumed her post in Nigeria five years ago, Ensign was a citizen of the world. She was born and raised in affluent Woodland Hills, California, the youngest of five siblings, and began traveling at an early age, from Singapore to Turkey to France. “Both my parents were airline pioneers,” said Ensign. “My dad started loading bags at Western Airlines in 1940 and went on to become an executive at Pan Am. My mom was a flight attendant at Western when you had to be a registered nurse.” Ensign earned her PhD at the University of Maryland, and soon made a name for herself as an expert in economic development, especially in Africa, teaching at Columbia and Georgetown, running a management program for HIV/AIDS clinicians in East Africa, researching the causes of the 1994 Rwandan genocide. In 2009, she was teaching and serving as associate provost at the University of the Pacific when she was recruited to run the American University of Nigeria.

Ensign’s job interview in Nigeria did not have an auspicious start. “I landed in Abuja, and nobody was there to pick me up,” she recalls. “So I hopped in a taxi, went to a crummy hotel and somebody called me at 2 a.m. and said, ‘Have you been kidnapped?’ I said, ‘No, I’m in a hotel.’ He said, ‘We’ve been looking for you all night!’”

Eager for a new challenge, she signed on, despite her California physician’s dire warning that her severe peanut allergy would kill her—peanuts are a dietary staple in Nigeria. (She has landed in the hospital once, following a restaurant dinner involving an undeclared peanut sauce.) She was joined in Yola at first by her daughter, Katherine, then in her early 20s, who had grown up adventurous, accompanying her divorced mother to rural Guatemala and far-flung corners of Africa. After their two-week visit, Ensign escorted Katherine to Yola’s tiny airport. As the jet taxied down the runway and took off, Ensign began sobbing. “I turned around and there were hundreds of people standing around the terminal, watching. I remember thinking, ‘They probably think that a crazy person has moved to Yola.’ But as I walked toward the terminal, people reached out their hands and grasped mine. I knew that I would be OK there.”

On the campus, Ensign settled into a four-bedroom villa (originally built for a traditional leader and his four wives), then set about remaking the university. She fired teachers, revamped security, forced out crooked contractors who were skimming millions of dollars. She commissioned buildings, including a hotel and library, started extracurricular programs, planted trees. And she required that all students spend time working directly with the underprivileged in Yola—tutoring street kids and coaching them in sports, distributing food and clothing in camps for people displaced by the fighting. The programs, she believes, serve as a strong counterweight to violent Islamist ideology. “Nobody knows any boys from Yola who joined Boko Haram,” she told me, sitting at a conference table in her office, a cheerful, sunlit space decorated with a large wall map of Adamawa State and a panel of colorful Nigerian folk art.

**********

Half a century ago, Nigeria seemed poised for greatness. Oil had been discovered in the Niger Delta in 1956—four years before independence—promising to shower the country in riches and ease tensions between the country’s predominantly Muslim north and its Christian south, a legacy of arbitrary colonial border-making. Instead, a series of rapacious regimes, both military and civilian, looted the oil riches—stealing some $400 billion in the half century since independence, according to some sources—deepened the country’s destitution and fanned sectarian hatreds.

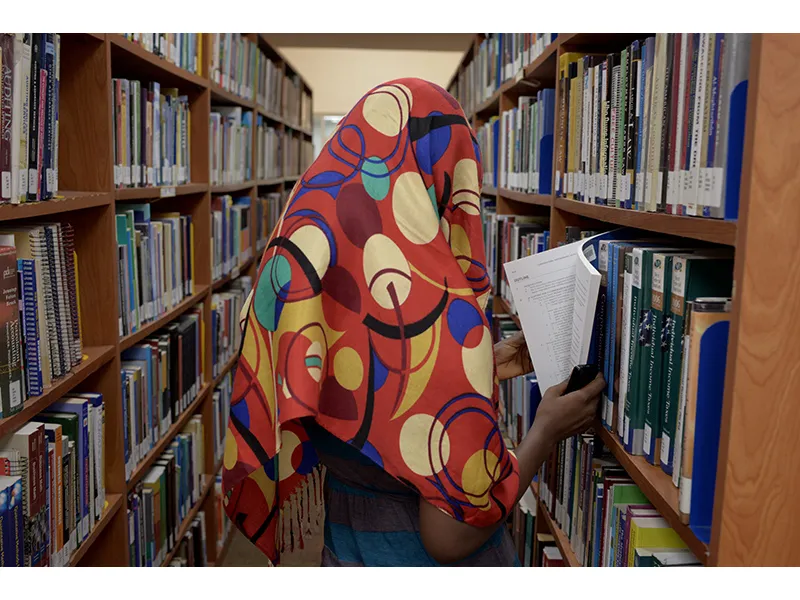

Education in Nigeria has suffered, too. The secular education model introduced by Christian missionaries never took hold in the north, where an estimated 9.5 million children attend almajiri, or Islamic schools. Overall, of the nation’s 30 million school-age children, about 10 million receive no instruction. Eighty percent of secondary school students fail the final exam that permits advancement to college and the literacy rate is just 61 percent. There is a federal and state college system, but it is chronically underfunded; the quality of teachers is generally poor; and only about one-third of students are female.

Ensign saw a chance to counter the corruption and dysfunction in Nigeria, which has the continent’s largest economy, by educating a new generation of leaders schooled in Western values of democracy, transparency and tolerance.

Ensign “has an incredible commitment to building a nurturing environment in which students can learn,” says William Bertrand, a professor of international public health at Tulane and vice chairman of the AUN board. “Her whole vision of a ‘development university,’ which has evolved throughout her career, is extraordinary.”

In fact, the values that Ensign holds dearest—secular education and intellectual inquiry—are anathema to Boko Haram.

Boko Haram began in 2002 in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno State, the poorest and least developed corner of Africa’s most populous country. Its founder, a self-taught, fundamentalist preacher, Mohammed Yusuf, who believed that the world was flat and the theory of evolution was a lie, inveighed against Western education. In 2009, following escalating skirmishes in Maiduguri between his followers and Nigeria’s security forces, Yusuf was arrested and summarily executed by Nigerian police. A year later his radicalized disciples, who numbered about 5,000, declared war on the government. In a wave of atrocities across the north, 15,000 people have died at the rebels’ hands.

The term “Boko Haram”—boko translates as “Western education” in the local Hausa language and haram as “forbidden” in Arabic—was conferred on the group by residents of Maiduguri and the local media. (Group members prefer to call themselves Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad, or People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teachings and Jihad.) “Boko Haram” reflects Yusuf’s deep hatred of secular learning, which, he asserted, had become an instrument for Nigeria’s corrupt elite to plunder resources. That the terrorists target schools is no accident.

At the all-female Chibok Government Secondary School, a sprawling compound of squat brown buildings surrounded by a low wall deep in the bush of Borno State, nearly all the students were Christians from poor farming villages nearby. For years, Boko Haram had been kidnapping girls and young women across the state, forcing them to marry and work as slaves in its camps and safe houses. The captors subjected the girls to repeated rapes, and, in a grisly reprise of the atrocities visited upon “child soldiers” elsewhere on the continent, forcing them to take part in military operations. Less than two months earlier, Boko Haram insurgents had killed 59 when they attacked a boys’ dormitory in neighboring Yobe State, locked the doors, set the building on fire and immolated the students. Those who tried to escape were shot or hacked to death. The government had subsequently shut down all public secondary schools in Borno State. But in mid-April, the Chibok school reopened for a brief period to allow seniors to complete college-entrance exams. The state government and the military had assured the girls and their parents that they would provide full protection. In fact, a single watchman stood guard at the gate on the April night that uniformed Boko Haram fighters struck.

Many girls assumed the men were Nigerian soldiers who had come to protect the school. “But I saw people without shoes, with these caftans on their necks, and I started going, ‘I’m not sure,’” one 19-year-old woman recounted to Ensign in a videotaped interview. “Deep inside me I felt that these people are not soldiers, not rescuers....They were telling the girls to go and enter the car, and I jumped through the window, I started running. I heard voices calling from behind me, ‘Come, come.’ I just kept on running. I was just in the bush [but] I knew I would find my way back home.”

As the 19-year-old made her getaway, a dozen armed men charged into the dorm. One group guarded the girls. Another ransacked the school’s kitchen and loaded vehicles with bags of rice, corn and other food. A third group set fire to the buildings. The attackers led the students out of the compound at gunpoint and into vehicles.

A handful of young women had the presence of mind to grab tree branches and swing out of the truck beds to freedom. Others fled during a stop to relieve themselves in the bush. The girls ran through the pathless scrubland, past stands of acacias and baobab trees, desperately hungry and thirsty, driven by the fear of being caught at any moment. One by one, they stumbled back through the fields to their families’ mud-brick houses.

Since then, Boko Haram forces have been repelled here and there, but they have not relented and none of the 219 female students held captive have been released.

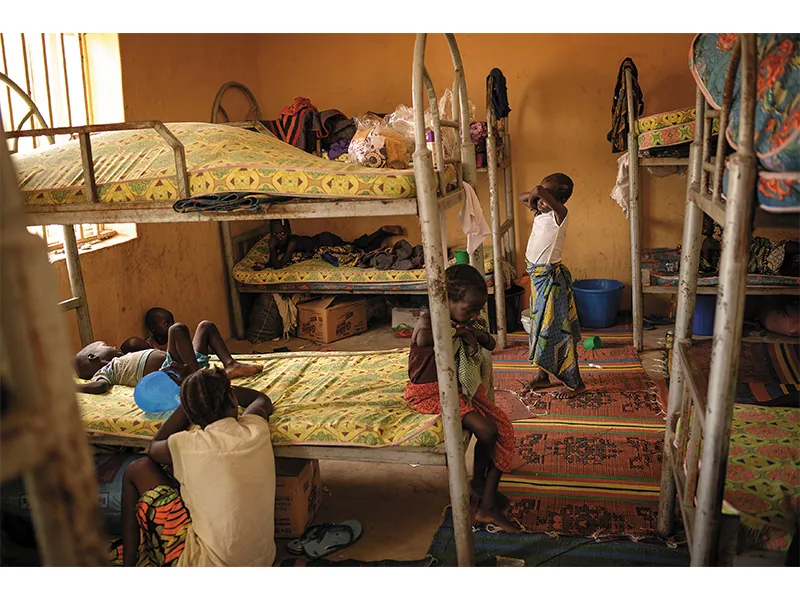

Last fall, fighters advanced to within 50 miles of Yola, imposing sharia law in the towns they occupied, burning books, kidnapping women, conscripting young men and executing those who resisted. Four hundred thousand people fled to Yola, doubling the city’s population. “Our employees were coming to us, saying ‘I have 20 people living at my house,’” Ensign recalls. “We started giving them rice, maize and beans...and every week the numbers were getting bigger.”

The Nigerian military advised Rawlins to close the campus. “The parents, students and faculty were pressuring her, saying, ‘You gotta leave,’” recalled Rawlins, who had heard that the rebels would not dare attack Yola because they were spread too thin and the city was well defended. “She remained calm and said, ‘We will do what we have to do, in the best interests of the students.’ She was vigilant and steadfast. She never wavered.” Weeks after I visited Yola, two Boko Haram suicide bombers attacked the city’s market and killed 29 people; an off-duty university security guard was badly injured. Still, Ensign remains undeterred. “I’m extremely hopeful,” she told me. “The [new] government is making all the right moves.”

**********

The American University of Nigeria was established in 2003 with a $40 million investment from Atiku Abubakar, a Nigerian multimillionaire businessman and the nation’s vice president from 1999 to 2007. Orphaned as a boy and educated by U.S. Peace Corps volunteers, Abubakar, who made his money in oil and real estate, remains something of a contradictory figure: Allegations of corruption have followed him throughout his career. At the same time, U.S. diplomats, educators and others say that Abubakar—known around the university as the Founder—has made a genuine commitment to improving Nigeria’s education system. “The man I’ve known for five years is devoted to education and to democracy,” Ensign told me. “I have never seen an inkling of anything that isn’t completely transparent and focused on trying to improve people’s lives.”

Yola is a hard place—a sprawl of corrugated tin-roofed houses and diesel-choked streets, fiercely hot in the summer, a sea of mud during the rainy season—and Ensign works to conjure a modicum of comfort. She has sought to surround herself with bits of home, even installing in the arts and humanities building a coffee bar called Cravings, complete with real Starbucks paper cups. “It’s our little American island,” she said. She plays squash at the University Club and jogs along the campus roads. She consumes the Italian detective novels of Donna Leon and the Canadian detective series by Louise Penny, and sometimes relaxes with DVDs of “Madam Secretary” and “West Wing.”

But the work is what keeps her going. She begins her day writing emails and discussing security with Rawlins, meets with faculty members and administrators, and teaches an undergraduate course in international development. There are weekly meetings with the Adamawa Peace Initiative, a group of civic and religious leaders she first convened in 2012. She’s also devoted to a “read and feed” program she started for homeless children who gather outside the university gates. Twice a week, under a big tree on campus, university staff members serve meals and volunteers read books aloud. “We’re up to 75 children,” she told me. “It helps to look in their faces and see that the little we’re doing is making a difference.”

In April came a happy surprise. Over a crackling phone line in her office, Robert Frederick Smith, the founder and CEO of Vista Equity Partners, a U.S.-based private equity firm with $14 billion under its management, said he would cover the tuition, room and board for all the Chibok girls who’d escaped or evaded the terrorists—an offer worth more than a million dollars . (Ensign had brought ten additional escapees to the university, for a total of 21.) “It was like winning a sweepstakes,” she told me. “I started crying.” Alan Fleischmann, who handles Smith’s philanthropic efforts, said the investor “was frustrated that there was an enormous outcry after the kidnappings and then it vanished. The impression was that they were dead or going to die. Then he learned that some had escaped, and said, ‘Oh my God, they are alive.’”

**********

Thirteen months after their desperate escape from the Boko Haram marauders, three Chibok girls—I’ll call them Deborah, Blessing and Mary—sat alongside Ensign in a glass-paneled conference room at the university’s new $11 million library. Ensign had allowed me to interview the young women if I would agree not to divulge their names and not to ask about the night of the attack. The young women seemed poised and confident, looked me forthrightly in the eye, displayed a reasonable facility with English and showed flashes of humor. They burst into laughter recalling how they gorged on a lunch of chicken and jollof (“one-pot”) rice, a Nigerian specialty, on their first day at the university—and then all became sick afterward. None had seen a computer before; they talked excitedly about the laptops that Ensign had given each of them, and about listening to gospel music and watching “Nollywood” movies (produced by the Nigerian film industry), Indian films and “Teletubbies” in their dormitory in the evenings. Blessing and Mary said they aspired to become physicians, while Deborah envisioned a career in public health.

Deborah, an animated 18-year-old with delicate features, recalled the day last August when she walked for miles from her village to the rendezvous point, accompanied by her older brother. Exhausted after hiking through the night, she was also deeply unsettled by the prospect of being separated from her family. “But my brother encouraged me,” she said. After an emotional farewell, Deborah boarded the minivan with the other girls for the drive back to Yola.

That first afternoon, Ensign hosted a lunch for the girls, and their parents, at the cafeteria. The adults fired worried questions at Ensign. “How long will you keep them?” “Do we need to pay anything?” Ensign assured them that the girls would stay only “as long as they wanted” and that they were on full scholarships. Later, she took the girls shopping, leading them through Yola’s market as they excitedly chose clothes, toiletries, Scrabble games, balls and tennis shoes. The girls admired their new sneakers, then looked, embarrassed, at Ensign. “Can you show us how to lace them up?” asked one. Ensign did.

The campus dazzled the Chibok girls, but they struggled at first in class—particularly with English. (Their native language is Hausa, spoken by most in Borno State.) In addition to providing the laptops, Ensign arranged for tutoring in English, math and science, and assigned student mentors who live with them in the dormitory and monitor their progress.

They remain tormented by thoughts of the Chibok students who remain in captivity. Three weeks after the abductions at their school, Boko Haram’s leader, Abubakar Shekau, released a video in which he threatened to sell the girls as slaves. The escapees watched with rising hope as the world focused on the Chibok tragedy. The United States, Britain and other countries put military personnel on the ground and provided satellite surveillance of the rebels. But as time went on, the mission to rescue the girls bogged down, the world turned away from the story, and the escapees felt a crushing sense of disappointment. In April, Nigerian President-elect Muhammadu Buhari—who campaigned on a pledge to crush Boko Haram—acknowledged that efforts to locate the girls so far had failed. “We do not know the state of their health or welfare, or whether they are even still together or alive,” he said. “As much as I wish to, I cannot promise that we can find them.”

At the beginning of their time at the university, says Ensign, the Chibok women “only wanted to pray with one another.” But as the months passed, Ensign made it clear that alternatives were available to help them. “They didn’t understand the concept of counseling, but we said, ‘This is here if you want it.’” A turning point came last Christmas, when Boko Haram fighters attacked a village and murdered the father of one of the Chibok escapees at AUN. “[The student] was totally devastated,” Ensign says. “Her mom wanted to take her home, and we said, ‘Can we work with her a little bit?’ and her mom agreed.” Ensign brought in Regina Mousa, a psychologist and trauma counselor from Sierra Leone, who met with the girl, calmed her down and made the other girls see the benefits of counseling.

Mousa set up thrice-weekly therapy sessions in the dormitory common room for groups of three to five girls, and conducted emergency individual interventions, sometimes in the middle of the night. Many of the girls, Mousa told me, were terrified of being alone, prone to collapse into sobbing, and, above all, stricken with guilt about having escaped while their friends were held captive. In therapy sessions, the girls go around the room, talking about their connections to the captives, voicing anguish as they imagine the others’ horrific lives. “I tell the girls that what happened has no reflection on them—it just happened at random, they were just in the wrong place at the wrong time,” Mousa says. “I tell them that they should now work hard, and aspire to do well so that these others will be proud, and that we’re sure that they will find them.” Recently she shared with them military and eyewitness reports “that the girls had been spotted alive in the Sambisa Forest,” a 200-square-mile former nature reserve 200 miles north of Yola. “That raised their hopes.”

Still, reassurance does not come easy. Boko Haram has struck the Chibok region with impunity, returning to attack some villages three or four times. Many Chibok women at the university have lost touch with family members who “fled into the bush,” says Mousa, increasing the girls’ sense of isolation. “Whenever there is an attack, we have to go through the intensive therapy again,” says Mousa. “Everything comes crashing down.”

On April 14, the one-year anniversary of the Chibok abductions, the women “were completely devastated,” Ensign recalled. “I went to meet with them. They were in each other’s arms, crying, they couldn’t talk. I asked ‘What can we do to help?’ They said, ‘Will you pray with us?’ I said, ‘Of course.’ We held hands and prayed.” Mousa met with them, too: “We talked again about the captured girls, and the need for the escapees to be strong for them and to move forward so that when the girls come back they can help them.”

Ensign stays in close contact with the Chibok women, throwing open her office, visiting them frequently in the dormitory common room. “The girls are coming by to say hello, many times during the week,” she told me. “I have them over to my house several times a semester for dinner.” Ensign, who calls herself “the world’s worst chef,” has her cook prepare traditional Nigerian food.

Ensign’s ambition is large—“I want to find and educate all Chibok girls who have been taken,” she told me—but she’s also a staunch advocate of the healing power of the small gesture.

One hot Sunday morning some months ago, she first took the girls down to the University Club’s Olympic-size outdoor swimming pool, and distributed the one-piece Speedo bathing suits that she had purchased for them during a break in the U.S. The girls took one look at the swimsuits and burst into embarrassed laughter; some refused to put them on. Using gentle persuasion, Ensign—who grew up on the Pacific Coast and is a confident swimmer and surfer—nudged them into the shallow end of the pool. The girls have shown up most Sunday mornings—when the club is deserted and there are no men around. “None had ever been in the water, some were scared, most were laughing hysterically,” Ensign recalls. “They were like little kids, and I realized this is what they need. They need to capture that fun childhood.” Half a dozen of them, Ensign adds almost as an aside, have already achieved what she was hoping for: They can swim.

Related Reads

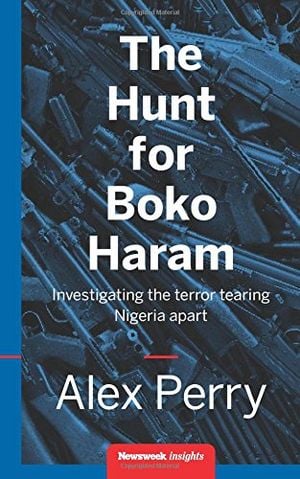

The Hunt for Boko Haram: Investigating the Terror Tearing Nigeria Apart

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)