The Extraordinary Disappearing Act of a Novelist Banned by the Nazis

Driven into exile because of her work’s “anti-German” themes, Irmgard Keun took her own life—or did she?

The greatest trick that Irmgard Keun ever played was convincing the world she didn’t exist. Once an acclaimed German novelist, the then 31-year-old Keun had been living the life of an exile in either France or the Netherlands since 1936. Three years earlier the Nazis had condemned her enormously popular recent novels, which dealt with subjects like independent women in Berlin’s seedy underworld, as “anti-German.” Keun was in Holland in 1940 when the fascists began their occupation of the Netherlands. With apparently nowhere left to turn, she took her own life—or so a British newspaper reported in August of the same year.

But the story was false. Keun had used it as cover to return to Germany to see her parents.

When you’re that good at disappearing, sometimes you can’t help staying hidden. Keun lived in obscurity until the 1970s, when her books were rediscovered by a new generation of German readers. The young Germans of the ’70s were trying to reckon with their nation's horrific past, which many of their parents were directly implicated in, so Keun’s steadfast refusal to conform to Nazis strictures during the Third Reich must have come as an inspiration to them. Recent English translations are now introducing those works to a broader audience and restoring Keun’s status as a unique, fearless novelist of interwar Germany. Her stories of average Germans, mostly young women, attempting to make their way in the world despite fascism are refreshingly ironic — unless, of course, you’re the fascist being belittled.

Keun’s disappearing act, amid the general chaos of Germany in the interwar and post-war periods, makes piecing together the author’s life a bit of a challenge. Award-winning translator Michael Hofmann has produced two recent English-language versions of Keun’s novels, yet is still unsure of her life story. “Definite biographical facts about Keun are very thin,” he admits. We know that Keun was born in Berlin in 1905 and began her professional life as an actress around 1921. She later turned her attention to writing, publishing the novels Gilgi, One of Us in 1931 and The Artificial Silk Girl in 1932. Both sold well, making Keun rich and famous. In a contemporary review, the New York Times praised Gilgi’s “freshness” as standing “in delightful contrast to the books written by men.”

But popularity came with a price. The Artificial Silk Girl tells the story of a young woman in contemporary Berlin who resorts to prostitution and theft on her quest to become a cabaret star. The Nazis had come to power the same year the book was published and disapproved of it vehemently. As one critical reviewer wrote, Keun produced “vulgar aspersions against German womanhood,” which were quite incompatible with Nazi ideas of refinement. “Anything like an autonomous woman was anathema to the Nazis,” Hofmann observes. Accordingly, Keun was blacklisted.

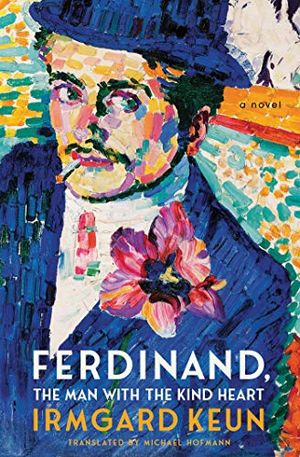

Ferdinand, The Man with the Kind Heart: A Novel

The last novel from the acclaimed author of The Artificial Silk Girl, this 1950 classic paints a delightfully shrewd portrait of postwar German society.

“She despised them,” Hofmann says of Keun’s feelings towards the Nazis. “To her, they were idiots dressing up in uniforms and shouting and goose-stepping about the place.”

Following her blacklisting and unsuccessful attempt to sue the Gestapo for the loss of income resulting from their confiscation of her work in 1933, Keun fled Germany for expatriate life, shuttling between France and the Netherlands. She joined other German writers in exile, like Thomas Mann, Stefan Zweig, and Joseph Roth, all whom had likewise run afoul of Nazi censors.

Unlike the historical fiction produced by those men, Keun’s work in exile remained focused on daily realities, becoming more and more explicitly political, though always with an ironic edge. In After Midnight, published in 1937, a young woman falls in love with her cousin, only to have her aunt sabotage the relationship by informing the police that the protagonist has insulted Nazi leader Hermann Goring.

Keun continued publishing, but the instability of exile, Nazi censorship preventing her from reaching German readers, and the growing certainty of war diminished her audience. Her small circle of fellow exiles and Dutch readers was minuscule compared to Keun’s former readership. The Artificial Silk Girl had sold nearly 50,000 copies before being banned; Hofmann estimates that her subsequent novels reached less than five percent of those readers. When news began circulating that she had killed herself, it certainly wasn’t unbelievable.

“She was still in Holland, in 1940, and her suicide was announced in a British newspaper,” says Hofmann of Keun. “Somehow, she took advantage of that, got some false papers, and went back to her parents just across the border, in Cologne.”

The finer details of this episode remain unclear. Whether Keun intentionally worked with an editor to place a false story, or whether she merely took advantage of a bureaucratic error due to the Nazi invasion, the fiction of her untimely demise persisted. How she thereafter crossed the border between the Netherlands and Germany, whether by obtaining papers through the seduction of a Nazi officer or straightforward forgery, is also a mystery. Regardless, Keun—or “Charlotte Tralow,” as became her nom de plume—was back in Germany.

Keun’s riveting return home has parallels to her novel Ferdinand, the Man with the Kind Heart. Written in 1950, Ferdinand is the story of a conscripted soldier who returns to Cologne from a prisoner-of-war camp to grapple with post-war life. In Keun’s signature ironic yet endearing style, the novel offers readers a glimpse of Germans amid the rubble and rations, women hoarding for sport and men celebrating their proof of de-Nazification. Germany is supposedly returning to normal, but Ferdinand, the narrator, just wants to return to living:

When I got back to Germany from camp, I still wasn’t a private individual. I wasn’t any Herr Timpe, Ferdinand Timpe. I was a returnee. … To be honest, I can’t stand the word “returnee.” It sounds a bit like the name of a vacuum cleaner or something. Something maneuverable. Gets in the corners and edges. It has something that smells of home and being looked after. Home for the homeless, home for fallen women, home for convicts, home for neglected children.

Unlike the defeated former Nazis or belatedly victorious anti-fascists, Ferdinand does not want to be part of the political life of Germany. He admits that, during Hitler’s rise, he was not involved in either their coup nor the opposition and was only dragged into the war. Now that World War II is over, he sees the Cold War simmering (Germany was formally divided between East and West in 1949) and once again wants no part of it. He wants to be a person, rather than a political subject. This insistence on independence, however, does push the reality of collective crimes like the Holocaust out of sight, where it is ignored by both Ferdinand and Keun.

“He’s charming, woozy, passive,” says Hofmann of Ferdinand. “Social and political movements mystify him, leave him indifferent. He’s like a speck of saffron swept up by a magnet, along with all the iron filings.”

Published for the first time in English last month, Ferdinand was Keun’s final novel. She spent the remainder of her life in or around Cologne, where she would die in 1982. Her former literary fame eluded her until the 1970s, when her books began to be reissued in German. English translations, some by Hofmann, some by his late colleague Anthea Bell, began appearing in the 2000s, and the literary world once again praised Keun as a unique voice amid interwar German writers.

The tragedy of this recent praise is that Keun faced such stark consequences in her own time for her novels. While the Nazis undoubtedly spared few of their victims, foremost the Jews that Ferdinand forgets, Keun puts into his mouth a pair of lines that might have been reserved to summarize the absurdity that defined her career: “It’s not so easy to write a love story in today’s Germany. There are strict laws.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.