The Fascinating Story of the Texas Archives War of 1842

Far from consequential, the battle over where the papers of the Republic of Texas should reside reminds us of the politics of historical memory

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e6/7b/e67b7e57-825c-4dc8-9607-11d35bcaf69d/angelina_expanded.jpg)

The French philosopher Jacques Derrida once declared, “There is no political power without control of the archive, if not of memory.”

Though he wasn’t writing about the Texas Archives War of the mid-1800s—and why would he considering its obscurity—he very well could have been. In the summer of 1839, when the nascent Republic of Texas faced a threat from the Mexican army to the south, a bitter dispute over the young nation’s archives brought to light how closely power and history are connected.

The conflict, in which state politicians used the archives as a means of bestowing legitimacy upon their preferred capital cities, is a fascinating moment in history. According to many Texas historians, it played a major part in why Austin is today the capital of Texas.

*******

The Republic of Texas grew out of the Texas Revolution, an 1835 uprising of U.S. colonists and Tejanos (Mexican-Americans that lived in southern Texas) that put up armed resistance against the Mexican government. The issue at hand was autonomy; the rebels refused to accept governmental changes that left total power with the national government and the Mexican president, instead of with the state and local government. Formed on March 2, 1836, the Republic of Texas governed as an independent nation until becoming part of the United States in 1845.

That brief nine-year period of self-governance was anything but peaceful. The Mexican government refused to recognize Texas as an independent state, and its army frequently raided the southern and western boundaries well into 1840s.

Modeled on the U.S. Congress, with a bicameral legislature elected by the population at-large (excepting free blacks and Native Americans, who were not considered citizens), the Congress of Texas represented about 70,000 people, according to the first and only census taken in 1840.

Five Texas cities served as temporary capitals in the republic’s first year of existence – jumping around to evade Mexican capture - before Sam Houston, elected the Republic’s second president (after interim president David G. Burnet), chose the city of Houston, already named after him, as the capital in 1837. The Republic’s archives, including military records, official papers, land titles, war banners and trophies, the seal of the government and international treaties, came from the city of Columbia to Houston with the new designation, according to historian Dorman Winfrey, who wrote about the Texas Archives War more than 50 years ago.

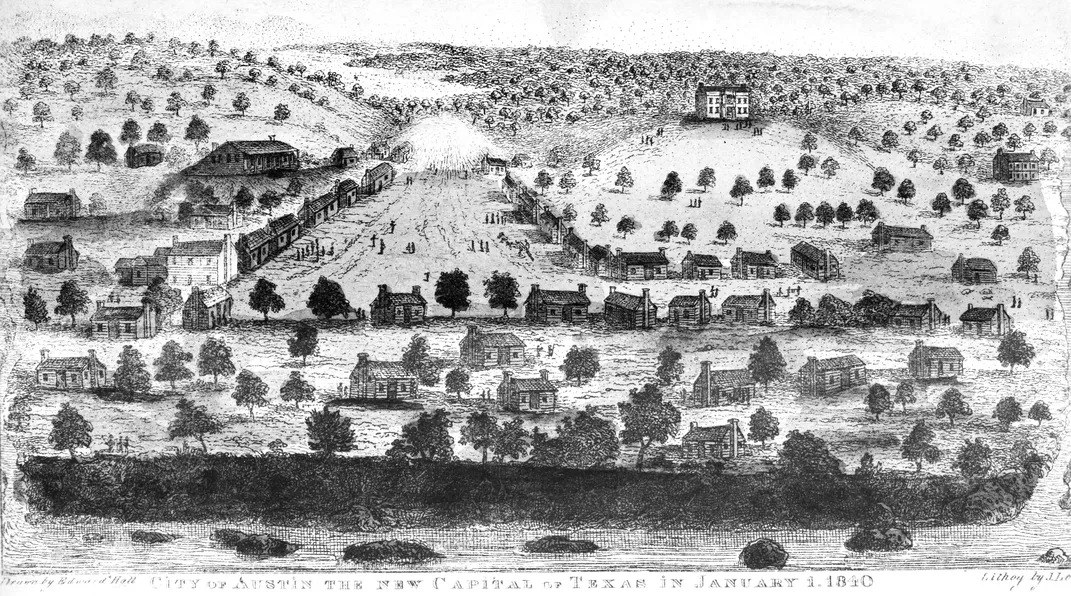

The next president, Mirabeau Lamar — an attorney from Georgia who believed that the literal extinction of Native Americans was necessary for progress — moved the capital to Austin the capital in 1839 because of the city’s central location. Detractors, the most vocal of whom was Sam Houston, felt that Austin was too remote, too undeveloped, and too close to Mexican and Native American enemies, mostly from the Comanche and Cherokee Nations. Houston (the city), meanwhile, enjoyed greater access to trade with its close proximity to the Gulf of Mexico.

Houston (the man) ascended to the presidency a second time in 1841, inheriting Austin as the capital, and he made no bones about how much he hated the city, often calling it "the most unfortunate site on earth for a seat of government," and refusing to move in to the official residence, preferring instead to take a room at a boarding house.

Having won three-quarters of the vote, Houston felt empowered to move the capital back to his namesake city. He agitated for such a change with the legislature, but representatives defeated his proposals. Austinites had hometown pride, but their obstinacy went beyond that. Losing the capital would stunt the growth of their rapidly developing city, and result in a drop in property values. Sam Houston was, in their minds, abandoning the seat of government and exaggerating the seriousness of the Mexican threat to achieve his political aims.

***

In early March of 1842, 700 Mexican troops under General Rafael Vasquez crossed the Republic of Texas borders, and by March 5 occupied San Antonio, about 80 miles from Austin. Officials declared martial law; many families left for somewhere safer.

In the aftermath of the attack, Houston feared the worst in what was to come. Letters to his fiancée express true concern of not only Mexican attack, but that Comanches would burn and destroy the city – and crucially its archives - as well. Houston felt strongly that Austin was not a safe place for the republic’s capital.

As he wrote on March 24, 1842:

“The destruction of the national archives would entail irremediable injury upon the whole people of Texas…Should the infinite evil which the loss of the national archives would occasion, fall upon the country through his [the President’s] neglect of imperious constitutional duty, he would be culpable in the extreme, and must justly incur the reproach of a whole nation.”

A couple of weeks earlier, President Houston had ordered his Secretary of War, George W. Hockley, to move the archives out of Austin to Houston, and Thomas “Peg Leg” Ward, the new commissioner of the General Land Office (which dealt with public lands and patents and maintained government records), was told to prepare the archives for transport.

The military commander in Austin, Colonel Henry Jones, had other plans. He opposed the order and convened furious citizens to discuss the proposition. Together, they formed a “Committee of Vigilance” to stop the transport and guard the archives. To them, the attack on San Antonio was overblown and being used a pretext to move the capital from their city.

Houston called a special session of Congress to resolve the matter, which met on June 27. He stressed the importance of moving the capital and the archives, but an indifferent legislature made no move to change the rule on the matter.

That fall, Mexican troops again attacked San Antonio, urging Houston to re-assemble the Congress, which this time met in Washington-on-Brazos, a new capital city that was neither Austin nor Houston, on December 5, 1842. Houston once again asked for support of an executive resolution removing the archives to the new capital — no matter what the so-called “seditious” citizens of Austin had to say about it, according to Patsy McDonald, author of The Texas Senate: Republic to Civil War, 1836–1861. Senate president Edward Burleson, who disliked Sam Houston, declined to support the procedural matter that would result in the transfer of the archives, and the motion stalled in a tie.

With no success through official channels, Houston took matters into his own hands – outside Congress, outside the government.

On December 10, he secretly ordered two Texas army officers – Captain Eli Chandler and Colonel Thomas I. Smith - to gather a force of 20 men, retrieve the archives from Austin with “secrecy, efficiency, and dispatch,” and take them to Washington-on-Brazos.

Wrote Houston on that day, "The importance of removing the public archives and government stores from their present dangerous situation at the City of Austin to a place of security, is becoming daily more and more imperative. While they remain where they are, no one knows the hour when they may be utterly destroyed."

On December 30, the covert force entered Austin in the early morning and were loading the archives, with an assist from Ward (the land office commissioner), into wagons when Angelina Eberly, a local innkeeper came across them. The owner of several city lots in addition to her inn, Eberly understood the symbolic value the archives had to the Republic. Having already lost the capital to Washington-on-Brazos, losing the archives would ensure Austin would be left out of the future of Texas. She quickly spread the word amongst Austinites, and a small, ad hoc army gathered.

According to Winfrey’s history, on Austin’s main thoroughfare, Congress Avenue, sat a loaded six-pound howitzer loaded with grapeshot—a remnant from the Republic’s earlier wars with Native Americans. She turned the muzzle toward the Land Office and “applied the torch, and the cannon was discharged,” according to D.G. Wooten, author of A Complete History of Texas.

There was a cry of “Blow the old house to pieces!” recounted Ward in a letter addressed to Sam Houston.

Some shots hit the Land Office, but “no one was injured and no damage was done,” wrote Winfrey. Ward, who had lost his right arm to a malfunctioning cannon earlier in his military career, was lucky to get out of harm’s way.

Smith, Chandler and their men took off with the archives in their wagons, pursued by about 20 vigilante Austinites, some carrying the cannon. Around noon the next day, at Bushy Creek, just north of Austin, the Austin mob held the troops at gunpoint, giving Smith the “alternative to surrender or fight,” wrote Winfrey, although there are several versions of the story. In the account written by Wooten, the mob forced Smith to move the archives back to Austin, while Ward’s states that the vigilantes hauled the archives back themselves.

Regardless, Smith was compelled to surrender the archives, which were dutifully returned to Austin. The “Committee of Vigilance” members celebrated their victory with a New Year’s party in the form of a hearty meal – some accounts say they even invited Colonel Smith to join in, and he accepted gladly. Others say he declined. Either way, the bloodless conflict was, for the time being, over.

***

With the Land Office damaged, the archives needed a new home, and according to historian Louis Wilz Kemp, “All records were then sealed in tin boxes and stored at Mrs. Eberley’s under day and night guard. An attempt to take them by force would have precipitated a civil war.”

This turn of affairs left Ward unhappy, as he wrote to Houston: “I have employed all the exertion I could to have them restored to this place, but in vain, and what the result may be, Providence alone can determine. Many threats have been made against me…but however dangerous or unpleasant my situation may be I will not complain if I can do a service to the Republic.”

Soon after, the Congress investigated Houston’s actions, and later reprimanded him. A Senate committee concluded that Houston had no legal reasons to attempt move the archives.

While the archives stayed in Austin, the seat of government continued to stay in Washington-on-Brazos, and Austin, without the status associated with capital cities, turned into a ghost town.

Throughout the first half of 1843, after repeated failures by Ward to reclaim the archives for his agency, he created a new Land Office in Washington-on-Brazos, where new archives were already being created as the government went about its business.

On July 4, 1845, at last and without much strife or anguish, the two archives were reunited in Austin; the Republic of Texas joined the United States of America a few months later, on December 29 of that year.

Austin, perhaps more than any other city in the U.S., has stridently asserted itself and its identity as a capital city from its beginning, and the Archives Wars was a fascinating blip on its journey to becoming the modern, self-assured city it is today. The issue of Texas the state’s capital wasn’t firmly resolved until 1850, when Texans voted by a large majority to choose scrappy, mighty Austin as their capital and seat of government. Its position as capital city was cemented with yet another, this time final, statewide vote in 1872, marking the end to a very strange, very long journey.

Sheila McClear is a journalist and author living in New York City.