This American Doctor Pioneered Abdominal Surgery by Operating on Enslaved Women

Glorified with a statue in the U.S. Capitol, Ephraim McDowell is a hero in Kentucky, but the full story needs to be told

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c1/73/c1736851-7861-4c00-8f99-0fc1d1690744/6264515826_bd57497557_b_resize.jpg)

Earlier this year, amid a larger national debate about Confederate monuments, a push to remove a statue memorializing 19th-century gynecologist J. Marion Sims from its location in Central Park made headlines. Sims conducted experimental fistula repair surgeries on enslaved black women, and in the process broke new medical ground, but at a high human and moral cost.

Sims, however, wasn’t the only doctor who used enslaved women as operative test cases for developing procedures, and he’s not the only one commemorated by a statue in an important place. A bronze model of Kentucky doctor Ephraim McDowell, known as the “father of abdominal surgery,” stands in the United States Capitol Visitor’s Center, a part of the esteemed National Statuary Hall Collection. It goes without saying that no memorial exists to the four enslaved women he operated on as he developed a surgical treatment for ovarian cancer.

Unlike many other cancers, ovarian tumors can grow to be quite large before causing symptoms including pain, abdominal swelling and digestive issues, and they are often accompanied by large fluid-filled sacs. Before the development of surgery, women simply lived–and died–with these painful and embarrassing symptoms. Some women, like fellow Kentuckian Jane Todd Crawford, assumed they were pregnant; in 1809, she thought her 22-pound ovarian tumor was twins.

The story of Crawford’s subsequent patient-doctor relationship with McDowell has been told and retold in the 200 years since the doctor published his account of the operation in 1817. The procedure that he performed on her remains the first-known successful ovariotomy on record and is also remembered as an early successful abdominal surgery. Not long after McDowell’s lifetime, doctors–starting with biographer Samuel Gross in the 1850s–began citing this noteworthy first in medical texts. The acclaim made McDowell a beloved Kentuckian–but public memory retains, at best, an incomplete record of his medical career.

Crawford, a 45-year-old white woman from Green County, sought medical attention when her “pregnancy” never came to term, and McDowell, who lived about 60 miles away, took on the case. He explained that her problem was actually an “enlarged ovarium.” For the time, the doctor was unusually well-suited to dealing with women’s bodies: McDowell’s teachers at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland helped shape early gynecology.

One of them, John Hunter, believed uterine growths, such as tumors, were in theory entirely operable. “There is no reason why women should not bear spaying as well as other animals,” he stated in a lecture in the late 1700s. Likely influenced by this perspective, McDowell told Crawford that the only thing he could do to help her was to perform surgery; if she could reach his practice in Danville, he would perform the experiment.

Crawford only had two options, says Lauren Clontz, assistant director of the McDowell House Museum in Danville, Kentucky: she could either die at home in the coming weeks or months or “get on a horse and ride three days, on horseback, in December, through the wilderness, and then get cut open and probably die away from her family and loved ones in Danville.”

At the time, abdominal surgery was viewed, justifiably, as tantamount to murder. Surgeons in the era saw no need to wash their hands and post-operative infection killed many who didn’t die on the table. McDowell’s surgery proved it was possible to perform at least some procedures.

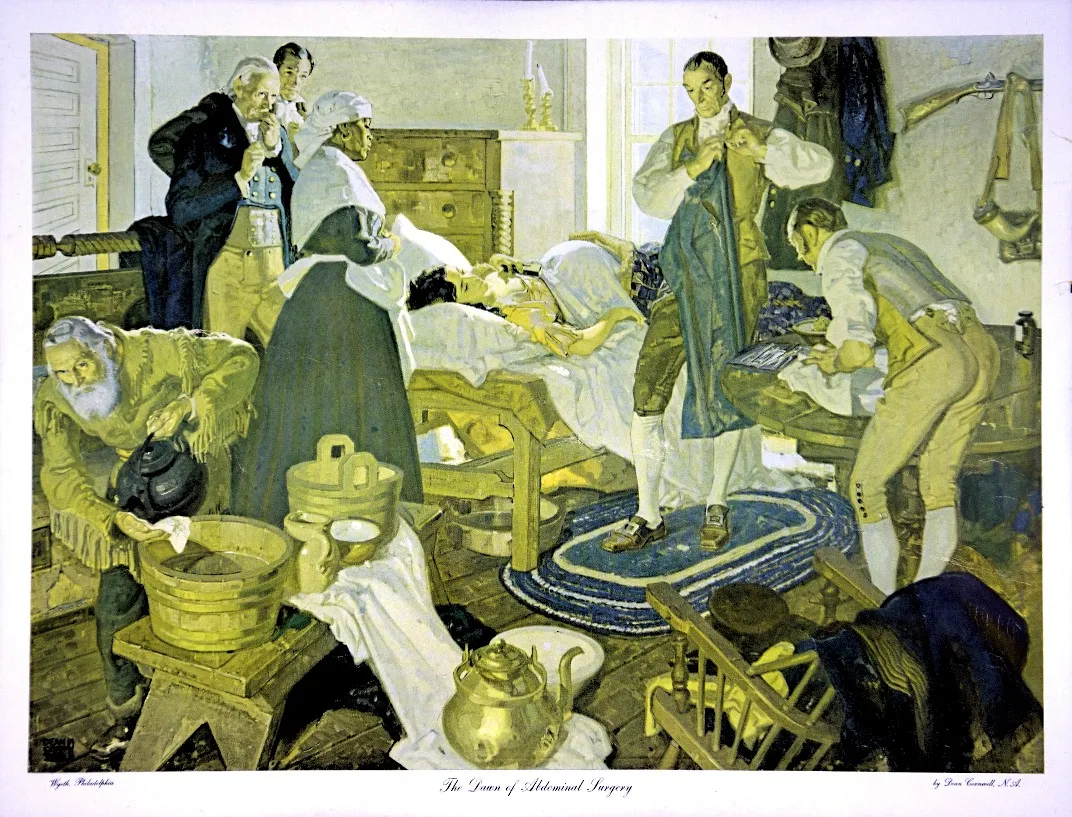

In the end, Crawford took that risk, Clontz says, and rested the tumor on the horn of her horse’s saddle during the multi-day ordeal. In an 1817 journal article, McDowell described making a nine-inch cut in Crawford’s left side and draining “fifteen pounds of a dirty, gelatinous substance” before he could take out the seven-pound tumor. During a portion of the approximately 25-minute operation, Crawford’s intestines were spilled out on the table, which was likely just a kitchen table brought into the regular bedroom where the operation took place.

According to several accounts, she recited psalms and sang hymns during the grueling procedure, which was performed without anesthetic–another innovation that lay in the future. However, her endurance paid off: she healed, staying somewhere nearby for the next 25 days, and then rode home, to live another 32 years, dying at the age of 78.

Only McDowell’s firsthand account of the procedure survives, though he was assisted by several other doctors. In his account, published eight years after the surgery, he includes many of the aforementioned details. This first-ever ovariotomy is considered a proud moment in Kentucky’s history.

In the early 1920s, a doctor named August Schachner produced a biography of McDowell that relied on Gross’s own work as well as other histories of the doctor’s life, such as that composed by McDowell’s granddaughter, Mary Young Ridenbaugh. (Clontz says the museum considers that Ridenbaugh biography is likely about 70 per cent fabricated–the product of familial imagination.) Included in Schachner’s biography is information about the centennial celebrations of McDowell’s first surgery, held by the New York Medical Association and the McDowell Medical Society of Cincinnati, Ohio.

Schachner was also active in a group of interested parties, including the Kentucky Federation of Women’s Clubs, who sought to purchase McDowell’s house and turn it into a museum, which opened in 1939. It was operated by the Kentucky Medical Association and then the state before finally becoming an independent non-profit.

Today, the McDowell House Museum sees about 1,000 visitors a year, who are generally guided through the house on tours. The museum’s central purpose is commemorating the story of that first ovariotomy, she says, as well as showing how a “frontier doctor” would have lived. "We love telling the story of Doctor McDowell and the surgery," she says. "That's really the highlight of the tour." But what the museum doesn’t discuss much, according to Clontz, are his “other surgeries,” the ones that would come after Crawford’s.

Between 1809 and 1818, McDowell wrote about having conducted five separate ovariotomies, including Crawford. The remaining four were all performed on enslaved women, making him–like Sims–a link in a chain of gynecological experiments performed without consent.

In the 1800s, the line between surgery intended to heal and experimental surgery wasn’t rigid the way it is today. In slave states like Kentucky, home to approximately 40,000 enslaved laborers around McDowell’s time, many of these experimental surgeries were performed on slaves. An extremely wealthy man and a prominent community member, he would have had many connections to prominent slaveholders. He himself was one. McDowell was also the son of Samuel McDowell, one of the founders of Kentucky, and was married to Sarah Shelby, the daughter of Kentucky’s first governor.

In the same 1817 article where he wrote about Crawford’s surgery, McDowell described two of those surgeries: in the first, an unnamed enslaved woman with “a hard and very painful tumor in the abdomen,” he actually didn’t think performing surgery was a great idea. “The earnest solicitation of her master and her own distressful condition” made him agree to try it.

Although the patient survived, the operation involved him plunging a scalpel directly into the tumor and draining it, causing a hemorrhage in the process that coated her intestines in blood. McDowell writes that he suggested several weeks of rest, as he had for Crawford, but his account implies that the woman didn’t spend those weeks near him getting regular checkups. She recovered, although in a later account he wrote that the tumor had recurred.

The second woman, also unnamed, worked as a cook. Her operation was more complicated and afterwards, he writes, she said she was cold and shaky. After a brief rest, he dosed her with “a wine glass full of cherry bounce, and 30 drops of laudanum.” She also recovered and in 1817 was employed “in the laborious occupation of cook to a large family.”

In a second article, published in 1819, McDowell recounted two more operations on enslaved women in 1817 and 1818, respectively. The third patient recovered, the fourth did not. McDowell drained this last patient’s growth multiple times over a series of months before attempting to remove it. “The second day after the operation she was affected with violent pain in the abdomen, together with obstinate vomiting,” he wrote. He bled her, then a common medical practice, but to no avail. She died the next day, likely of peritonitis.

Harriet Washington, a medical historian and the author of Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present, says there’s no way to know if Crawford’s surgery was even the first-ever ovariotomy, as so many sources maintain. "It's the first recorded procedure he did,” she says. “That doesn’t mean it was the first procedure.” Whether he had attempted the procedure before, either on enslaved, black patients or free, white patients, is entirely lost to the historical record.

Black women–like enslaved laborers more generally–were frequently the subjects of medical experiments, because they were “convenient,” she says. Unlike white women such as Crawford, who clearly gave consent to the procedure, to operate on an enslaved woman, all that was needed was the permission of her owner. Whether they also consented to the procedure is “almost beside the point,” Washington says. “That’s because of the nature of enslavement.” The enslaved women weren’t capable of saying a free “yes” or “no,” because, quite simply, they weren’t free.

A testament to this “convenience” is the fact that while McDowell’s first recorded operation was on a white woman, the operations that followed it, and that he chose to publicize, were all conducted on enslaved women. When developing a surgical technique that was widely perceived as equivalent to murder and was well outside medical convention, he chose to “experiment” primarily on enslaved women. “It was on the bodies of black women that these surgeries were perfected and predicated,” Washington says. That's not to say that he was or wasn’t genuinely trying to heal these women, whether because of the Hippocratic Oath to "do no harm" or because of their monetary value to slaveholders–it’s to say that their health, intrinsically, didn’t need to matter to him. They certainly didn’t get the same focus or treatment as Crawford.

And that convenience is reflected in how he has been memorialized. McDowell owned at least 10 to 15 slaves in his main residence, where the Crawford surgery was performed, and more on his two farms, says Clontz. But there’s no record of his attitude towards slavery, or whether he ever treated any of those slaves as a physician, she says. What’s remembered is what was considered important by the physicians who promulgated the story: his daring and innovative surgery on a brave white woman.

“We can’t think we have the entire historical record here,” says Washington. Certainly, that one story about McDowell discounts a large portion of the existing historical record about his development of the ovariotomy. What we know about that surgery and his subsequent surgeries is based on a very small number of documents: the two reports that McDowell published and a subsequent letter in which he boasted about having performed a total of 12 ovariotomies, with only one fatality.

We don’t remember the woman who got cold shakes after being forcibly cut open, or the woman who died of an excruciating infection in his house, or the woman lying on his table covered in her own blood. What’s remembered is him and Jane Todd Crawford, who bravely survived her operation spent singing hymns.

At the McDowell museum, what’s mentioned about these additional surgeries “is up to the individual docent, what they want to say,” says Clontz. When she’s working with guests, she doesn’t generally bring up the fact he conducted other surgeries at all. If she’s asked, she says, “I tell them he did about 10 or 11 other similar surgeries,” but nothing beyond that. These surgeries are also not memorialized in the exhibits of the house.

All of this is an illustration of the need for a careful reexamination of what public memorialization really tells us. “We tend to talk about achievements or supposed achievements, and we tend to ignore the morally bankrupt or morally troubled steps that these people have taken to achieve what they have achieved,” Washington says. “We act as though moral and ethical problems are not at all important.”

It’s a failing of our society, she says, one that the statues of men like J. Marion Sims or Ephraim McDowell reflect. While there is no concerted movement calling to remove McDowell from the Statuary Hall collection, as there is for Sims from Central Park, the debate would likely mirror those already underway about Confederate generals and prominent slaveholders. But until all of the story is told, one that includes the lives of four enslaved women, any memorial to part of it is insufficent.