The FBI’s Fake Russian Agent Reveals His Secrets

In an exclusive interview, a retired FBI agent who posed as a KGB officer finally spills the beans about his greatest sting operations

:focal(510x316:511x317)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b0/d5/b0d53cf7-cdf4-4edc-a7df-7b3319002795/nov2016_d01_fakerussian-wr-v2.jpg)

Dimitry Droujinsky is on his third cup of black coffee when he starts talking about his toughest case. “It was what we called in the bureau ‘an old dog case,’” he says. He smiles. “Twenty-eight years old.” But when it comes to tracking spies and discovering which secrets they have betrayed, counterintelligence never forgets.

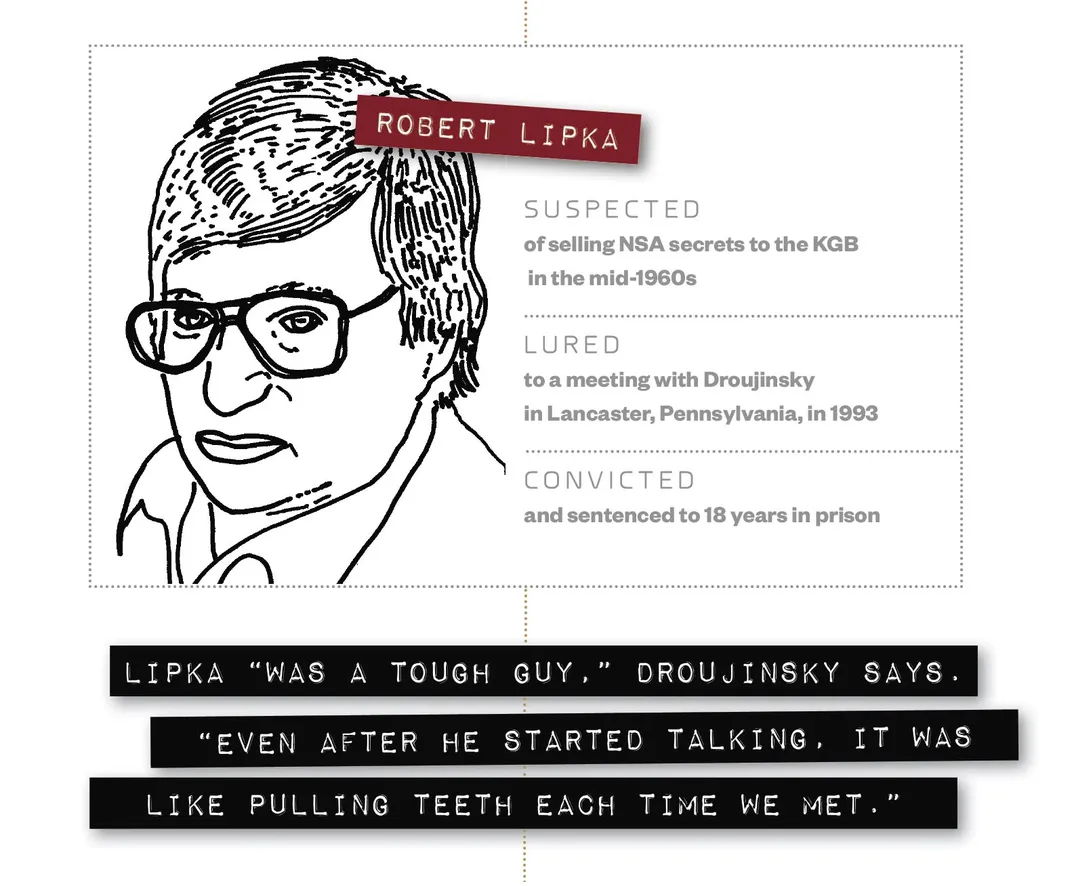

We’re alone, sitting in the dimly lit back room of a restaurant in Northern Virginia. The case he’s talking about unfolded in the spring of 1993 in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. It involved a clerk who worked for the National Security Agency for three years in the mid-1960s, in a branch that gave him access to classified documents transmitted or received from NSA stations all over the world. Federal agents had evidence that he had sold some of that supersecret organization’s most sensitive information to the KGB, but not enough to prosecute him. “I said I knew it would be hard,” Droujinsky says. “I didn’t realize how hard.”

He booked a motel room in Lancaster. Government technicians set up recording equipment in the next room and trained a video camera through a pinhole in the wall. And if the target refused to meet at the motel? “Just in case,” Droujinsky says, sipping more coffee, “I had a briefcase with a recorder.”

His moment had come. He picked up the phone in his motel room and dialed. When a man answered, Dimitry Droujinsky did what the FBI depended on him to do.

“Ah, Mr. Robert Lipka?” he said, with the slightest trace of a Russian accent. “My name is Sergei Nikitin. I am from the Russian Embassy in Washington, D.C.”

“Yes?” Lipka replied cautiously.

“And my superiors in Moscow have instructed me to meet with you and discuss something very important about your safety and security. You understand?”

Lipka did not reply.

“I am here today in the Lancaster area,” Droujinsky said. “Can you meet me at the Comfort Inn?”

**********

When he dialed Lipka’s number, Droujinsky was already a legend inside the FBI. He spent much of his career, from the 1960s to the late ’90s, impersonating a KGB officer or some other enemy of the United States to catch spies and terrorists. His acting was Oscar-worthy, but he toiled in the shadows, his work unknown. He guarded his identity and appearance so closely that on the rare occasion he testified in court, he took the stand disguised in a wig, thick glasses, beard and mustache. The FBI has never commented publicly about his work, but Phillip A. Parker, a veteran counterintelligence agent and former deputy assistant director for operations of the bureau’s intelligence division, knew Droujinsky well. “He was a valuable asset to the FBI,” Parker told me. “He was very talented.”

He handled an array of cases—in 1987, he impersonated an Arabic-speaking playboy aboard a yacht in the Mediterranean to lure the notorious airplane hijacker Fawaz Younis into the FBI’s hands—but Droujinsky was particularly useful in his role in the Cold War. “A lot of people were trying to sell secrets in those days,” he says. “Who pays the most? The Russians. So they went to the Russians. We needed someone to pose as a Russian.”

Russian happens to be one of the nine languages Droujinsky speaks, but the job also required agility and urgency. “If the guy calls the Soviet Embassy and offers to sell secrets, you have to move right away. He might change his mind or meet with an actual Soviet agent,” he says. It was an open secret in Washington that the FBI wiretapped and watched the Soviet Embassy, though a number of would-be spies either were unaware of that or thought they could avoid detection by concealing their identities. “The first thing I did was to try to keep them away from the Soviets. I always said, ‘Don’t contact the Soviets again, the Soviet Embassy. I’m the guy who handles these cases for them.’”

I ask how many KGB impersonators the FBI had. “I was the one,” he says. “I worked for the FBI, but also the military, the CIA. Sometimes the other agencies called on me and I might be out of town or out of the country on a case.” He trained four or five other Russian-speaking FBI agents, he says, “but they would only be called on if I was not available. I was the one.”

I first heard from an intelligence source in the mid-1990s that the FBI had a “fake Russian,” and I had chased him ever since. An FBI contact of mine cautiously confirmed that the bureau had an agent who impersonated a KGB spy handler, but would say no more. After I discovered his name buried in a news article about a court case, I found it in a phone book—a seeming stroke of luck, since most FBI agents are unlisted. But when I called the number I got his son, who has the same name. The son agreed to pass on my request for an interview, and eventually relayed his father’s reply: Sorry, but no.

I wrote to Droujinsky in 1999, a year after he retired, through the FBI. I got no reply. Years went by and other projects intervened. In 2014, I asked the FBI if it would put my request to him once more; I was told that after several emails from the bureau, he agreed to get in touch with me—but he never did.

I’d about given up when I managed to turn up a telephone number for him several months ago. When I called, his wife answered and took a message. To my surprise, Droujinsky called the next day and agreed to meet over lunch. I asked him why, after all these years, he had decided to talk to me. “I’ve been out of the bureau for many years,” he told me, “and I didn’t think it would jeopardize anyone.” He deflected my offer to meet at his home, but unlike other counterspies I have interviewed, he said I was free to quote him by name. One lunch led to eight more; over ten months, the FBI’s bogus Russian discussed his life and career with a reporter for the first time.

At our initial meeting, at an Italian restaurant near his home, he was relaxed and friendly. I told Droujinsky I knew of five or six cases where he had convincingly posed as a KGB officer.

“Oh, no,” he said, “I was involved in 45 or 50.”

Startled, I asked how many of those spies he had sent to prison.

“About half.”

**********

When Robert Lipka answered Droujinsky’s phone call in the spring of 1993, he was living near Lancaster with no visible means of support beyond his wife’s salary as a postal worker. Bespectacled, approaching 50 and weighing almost 300 pounds, he spent his days betting on the horses at racetracks in Harrisburg and Delaware Park, near Wilmington.

The year before, a KGB archivist in Moscow named Vasili Mitrokhin had delivered to British intelligence Soviet files he’d copied over the last 20 years, at first on scraps of paper he hid in his shoes. He identified several possible American spies, including Lipka. The information was passed on to the FBI, and it led to the phone call from the alleged Sergei Nikitin.

Fifteen minutes after he got off the phone, Lipka pulled up at the Lancaster Comfort Inn in a blue-green Chevrolet van. Droujinsky was waiting outside. Lipka recognized him by the description he’d provided on the phone.

Wary, Lipka refused to meet inside the hotel, but invited him into the van. “We don’t forget our friends,” Droujinsky said after climbing into the passenger seat. He placed his briefcase between them.

“I have no contacts with NSA at all anymore,” Lipka said. “I don’t know that I can help you.” He drove about a mile and pulled into a factory parking lot. Lipka talked about his bad back and horse racing, but answered no questions. He did let it drop that he had met his KGB “handler” at a park in New York City, where they played chess.

“Oh, you play chess?” Droujinsky asked.

“You didn’t know?” Lipka asked incredulously. Droujinsky shook his head.

Lipka demanded his code word. “You know what it is.”

His visitor explained that he was stationed in Washington, the files were in Moscow.

“You don’t have a code word for me?” he asked suspiciously.

“No, I don’t.”

With his finger, Lipka traced “R---” in the dust on his dashboard. “Complete that,” he said. Then he erased it.

Unless his visitor could provide the code word the next time they met, Lipka warned, “I won’t say anything.”

That afternoon, the FBI case agent, John W. Whiteside, and agents from the NSA met with Droujinsky at the motel to figure out how to deal with the code-word dilemma. “It was not necessarily four letters,” Droujinsky told me. “It could have been a longer word or the beginning of a phrase or sentence.” A major spy case was hanging by a very thin thread.

Droujinsky had been thinking about Lipka’s reaction to his faux pas concerning chess. “I wondered if the code word could be ‘rook,’” he says, referring to the chess piece that resembles a castle. It was a million-to-one shot, but it was all they had. “I said the next time I meet him I’m going to try it out.”

They met again the next morning in Lipka’s van in the motel parking lot. Surveillance cameras were trained on them when Droujinsky asked, “Does ‘rook’ mean anything to you?”

“That’s it!” Lipka cried.

“He threw his hands up and his head back, obviously greatly relieved, all of which we captured on video,” Droujinsky says. From then on Lipka met with him as many as a dozen times and talked—circuitously, opaquely—about his spying days so long ago. “He was a tough guy,” Droujinsky says. “Even after he started talking, it was like pulling teeth each time we met.”

It was enough: Lipka was arrested in 1996. After pleading guilty to espionage—a crime for which there is no statute of limitations—he was sentenced to 18 years. “I feel like Rip Van Spy,” he told the judge. “I thought I had put this to bed many years ago. I never dreamed it would turn out like this.” He served half his sentence and was released from prison in 2006. He died in 2013, at the age of 68.

**********

At age 77, Droujinsky is a compact, quick-witted man who enjoys fine cigars and classical music and holds a black belt in tae kwon do; until he retired, he worked out with sparring partners at the FBI gym. He was born in Palestine, the son of Russian emigrants who met and married there. “The whole family is Russian Orthodox,” he says. “A lot of Russians came to Palestine as pilgrims to visit the holy sites and stayed.” (His grandfather, an officer in the White Army, was killed fighting the Bolsheviks during the Russian Revolution.) Of the nine languages he speaks, he is fluent in English, Russian, Arabic and French. “I was enrolled in a French school in Palestine, and I studied English, French and Arabic for 12 years, from kindergarten through high school. We spoke Russian at home,” he tells me. “I spoke Hebrew like a Jewish boy because growing up all my buddies were Jews. I also speak a little Greek, Armenian, Spanish and Italian.”

When he was a teenager, “my aunt went to the U.S. and said it’s very nice here, why don’t you all come here?” he says. “It took us five and a half years from the time we applied at the U.S. Embassy in Jordan for us to be allowed to immigrate to the United States.”

Not long afterward, at age 21, he joined the Marines. “I felt very grateful to the U.S. for letting us come here. I felt I should do something for the country,” he says. “I found out they were the most disciplined, the toughest and the best. So I said I’ll go with the best.” He spent four years in the Corps. “I was in Guantánamo Bay during the Cuban missile crisis. That was hairy.” He also did two six-month cruises with the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean.

Droujinsky married while in the Marines, and afterward earned a degree in French with a minor in English at St. Peter’s College, a Jesuit institution in Jersey City. He had to decide what to do next. “I realized I had all these languages,” he says. “I thought of the U.N., the State Department. I had a full scholarship for graduate work at the University of Chicago. Then I saw a magazine article that said the FBI had linguists as special agents.”

He called the bureau’s New York office to confirm it. “I thought this might be an exciting career,” he says. “The more I thought, the more excited I got. I applied, and everything went through.”

After reporting to the bureau in March 1968, he trained at Quantico, Virginia, spent his first office assignment in New Orleans, and then was sent to the field office in Washington, D.C. Almost immediately he began working as a specialist in what he prefers to call “false flag” cases, an intelligence term for when an agent pretends to be working for a country other than his own.

His first target was a Navy sailor in Norfolk, Virginia, who dealt with sensitive information about submarines; the bureau discovered that he had contacted the Soviet Embassy in Washington. Droujinsky’s supervisor suggested that he call the sailor and say he was a Russian spy. “I did, twice, but he refused to meet me,” he says. The sailor was later interrogated and convicted without Droujinsky’s help, but his superiors realized their young agent was a natural actor. And so a star was born.

Although he was not armed, some of his targets were. “One of them said, ‘If I find out you’re FBI, I’ll kill you,’” he says, yet he didn’t carry his gun, his badge or even his driver’s license. “I did not worry much about spies,” he says. “They do it for the money. The ones I was concerned about were terrorists.” In dealing with them, he always wore a disguise.

He never used counterfeit KGB credentials; his targets, he says, “just assumed I was real.” If a suspect demanded proof of his identity, he planned to use his improv skills to deflect the question. No one ever asked.

**********

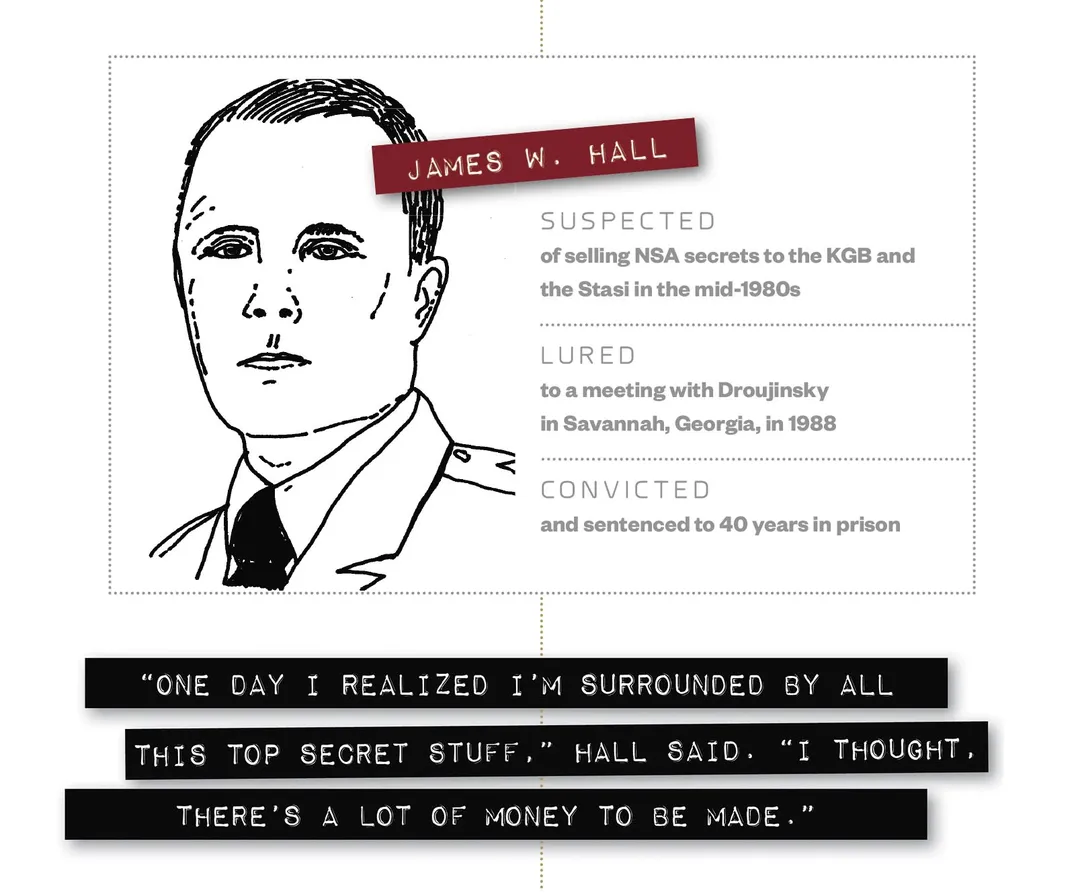

The most damaging spy he ever caught, an Army warrant officer named James W. Hall, came along 20 years later. “An NSA official told me he did $3 billion worth of damage to our country,” Droujinsky says.

Hall, born in New York City in 1957, dropped out of junior college and joined the Army in 1976. He was stationed in Germany for most of his career and married a German woman. For four years, in the early to mid-1980s, Hall worked at Field Station Berlin, the NSA’s key listening post in West Germany. There, atop Teufelsberg, the Devil’s Mountain, built high above the city on rubble left from World War II, he and other technicians eavesdropped on the Soviet Union and East Germany, collecting signals intercepted by high-powered antennas inside radomes, giant globes visible atop the hill. The SIGINT (signals intelligence) was invaluable to the NSA—and, as Hall determined soon enough, to others as well. He sold U.S. secrets to the Soviets and the Stasi, the East German intelligence service, for an estimated $300,000.

In 1988, Hall was transferred to Fort Stewart, Georgia, about 40 miles southwest of Savannah. Around the same time, as East Germany headed toward collapse, an East German professor who had been hired by the Stasi as an interpreter for its dealings with Hall volunteered his services to the West. That December, the interpreter was brought to a hotel in Savannah, where he set up a meeting between Hall and Droujinsky. The interpreter introduced Droujinsky as a KGB man named Vladimir and left the room.

Hall, who wore civilian clothes, wasn’t shy. As Droujinsky recalled their conversation, Hall said, “One day I realized I’m surrounded by all this Top Secret stuff. I thought, there’s a lot of money to be made.” Droujinsky had come prepared, with two packages containing $30,000 each in bundles of $100 bills wrapped in rubber bands. “Hall could see the money sticking out of my briefcase,” he says.

Soon Hall was bragging about his exploits as a communist agent. “He had been told to slip an envelope into a slightly open rear window of a locked car. But he complained the slot was so small he had trouble feeding through all the documents,” Droujinsky says. “So he was given an apartment with a photocopier to make his spying easier.”

Vladimir flattered his target—“I said Moscow really appreciated his work and wanted me to meet him in person”—and then moved to close the deal: “I told Hall ‘our brothers’ [meaning the East Germans] are sharing what you have given them, but we don’t think they are sharing everything. Moscow doesn’t think the Germans are paying you enough.’ And of course the money is sitting right there.”

Hall handed over three documents marked Top Secret and Secret in exchange for the money.

“As soon as Hall walked out into the parking lot with the $60,000, he was arrested,” Droujinsky says. FBI agents standing by in Tampa also arrested a Turkish national named Huseyin Yildirim, a fellow employee of Hall’s at Field Station Berlin who had acted as a courier between him and the Stasi. Hall, sentenced to 40 years in a military court, served 22 years and was released in 2011. Yildirim was sentenced to life but released after 14 years in a prisoner exchange with Turkey.

**********

One factor in Droujinsky’s success was his restraint. His conversational English has no discernible accent, but sometimes he would deliberately mispronounce a word—“For example, I would pronounce Washington as Vashington”—and he had a gift for malapropism.

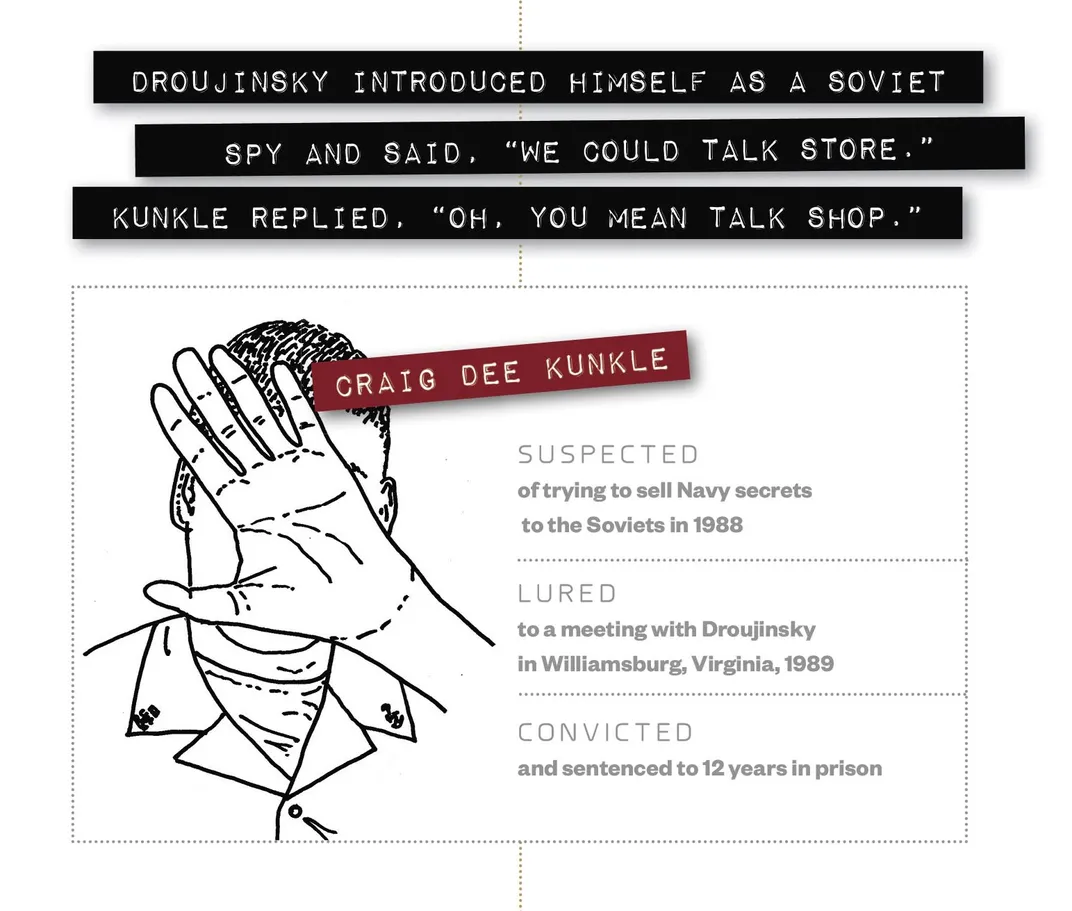

After the FBI learned that Chief Petty Officer Craig Dee Kunkle, a specialist in anti-submarine warfare, called the Soviet Embassy in Washington in December 1988 to offer information, Droujinsky contacted him and got him to agree to a meeting at an Econo Lodge in Williamsburg, Virginia. There Droujinsky introduced himself as a Soviet spy and said, “We could talk store.” Kunkle, confused at first, “Finally said, ‘Oh, you mean talk shop.’”

A California native and the son of a retired naval commander, Kunkle had once been named the Atlantic Fleet’s Sailor of the Year. But the Navy discharged him in 1985 after he committed several incidents of indecent exposure at a Hawaiian beach where Navy women liked to sunbathe. During a series of meetings at the motel, Kunkle made it clear that he wanted to sell Navy secrets to the Soviets to avenge his discharge.

Kunkle proposed to rent a condo on an upper floor of a building in Norfolk, Virginia, and watch when submarines left the base there, Droujinsky says. “The Russians wanted to know what time the subs left so they could track them. He said I could even bring some of my people there to watch the subs.” Arrested in January 1989 and facing a possible life sentence for attempted espionage, Kunkle, then 39, pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 12 years.

In another case, the FBI was running a double agent against the Soviets, an Army lieutenant of U.S. birth but Russian heritage. “You can never be sure about a double agent,” Droujinsky said. “So we decided to give him one final test. If he passed, we would keep it going. If not, we would close the case.”

The lieutenant agreed to meet Droujinsky, again posing as a KGB agent, at the Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site near Louisville. “I gave him cash, about $2,000, that was part of the test. And I said, ‘This Lincoln was a smart biscuit.’ The double agent looked puzzled, and I said, ‘Oh, I meant to say a smart cookie.’”

The double agent passed the test: He turned the money over to the FBI and told the bureau all about his conversation with the Russian “agent.” “He said, ‘The Russians screw up every time. Can you imagine them saying Lincoln was a smart biscuit?’” Droujinsky was pleased. “We ran him as an agent against the Soviets for five years.”

**********

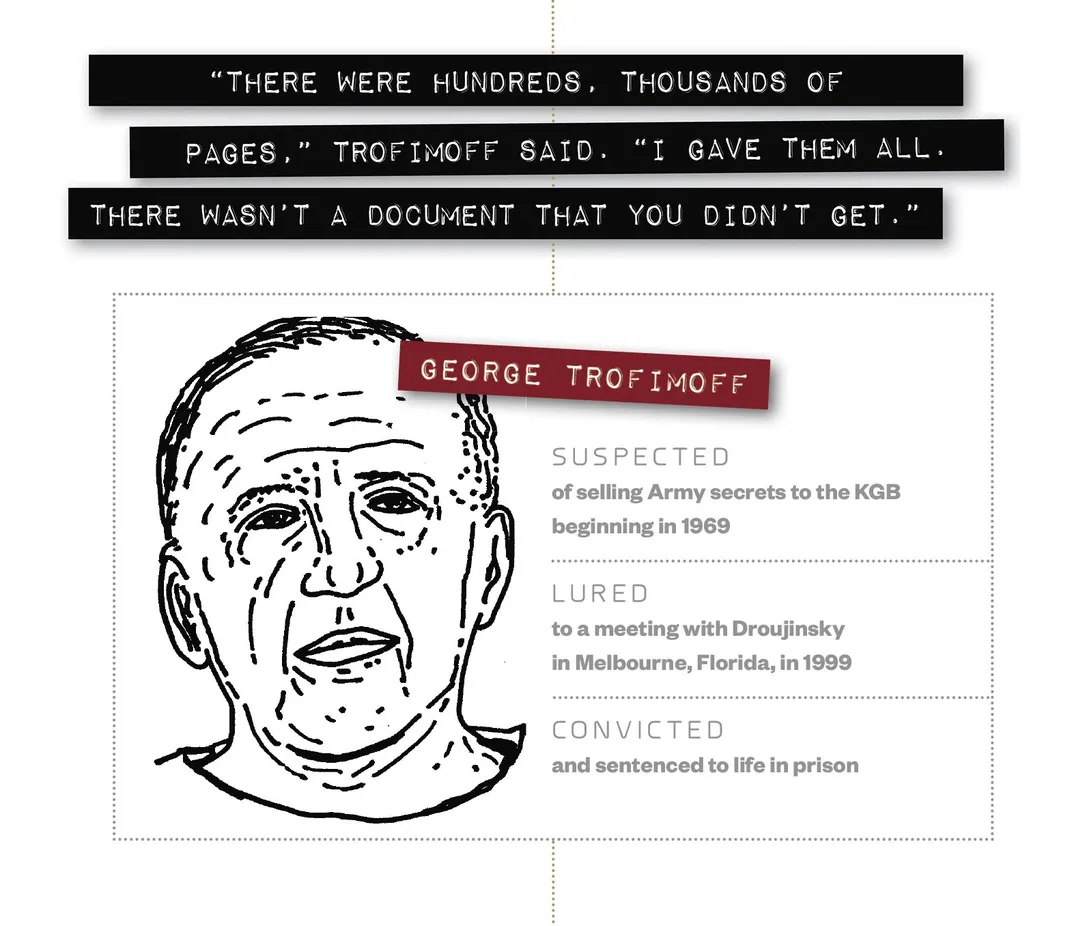

George Trofimoff was a charmer with a taste for fine cars and high living, a man who went through five wives. His appetites required more money than he could earn as a civilian working for the U.S. Army in Germany. Born in Berlin to Russian émigré parents, he became a naturalized U.S. citizen and rose to head of the Army’s element in the Joint Interrogation Center in Nuremberg, which debriefed defectors from Eastern Europe. He had access to large amounts of classified information, including NATO’s order of battle, and in 1969 he began selling secrets to the Soviets. He photographed documents and passed them through a Russian Orthodox priest named Igor Susemihl, a childhood friend who was working for the KGB.

Trofimoff’s espionage was so valued that he was presented with the Order of the Red Banner, one of the highest Soviet military awards. Prosecutors would later say Moscow paid him at least $300,000 over 25 years.

He retired to Melbourne, Florida, in 1995 as a colonel in the Army reserve. But the same notes that had led counterespionage agents to Robert Lipka also pointed to Trofimoff.

Deeply in debt—and so short of cash that he took a job bagging groceries—Trofimoff was cautious but receptive when a telephone call came from a Russian intelligence officer named Igor. There were many phone calls before Trofimoff agreed, in February 1999, to a meeting at a Comfort Inn near his home. Igor was, of course, Droujinsky. Over six hours, videotaped by FBI technicians in the next room, Trofimoff said he was desperate for money. His job in Germany had been “a gold mine,” he told Droujinsky. “There were hundreds, thousands of pages. I gave them all. There wasn’t a document that you didn’t get.”

After a series of admissions like that, Trofimoff was arrested in June 2000 and tried in federal court in Tampa. That was one of the cases in which Droujinsky testified in disguise. The jury took only 90 minutes to convict Trofimoff of espionage. He was sentenced to life in prison and died at the federal penitentiary in Victorville, California, in 2014. He was 87.

**********

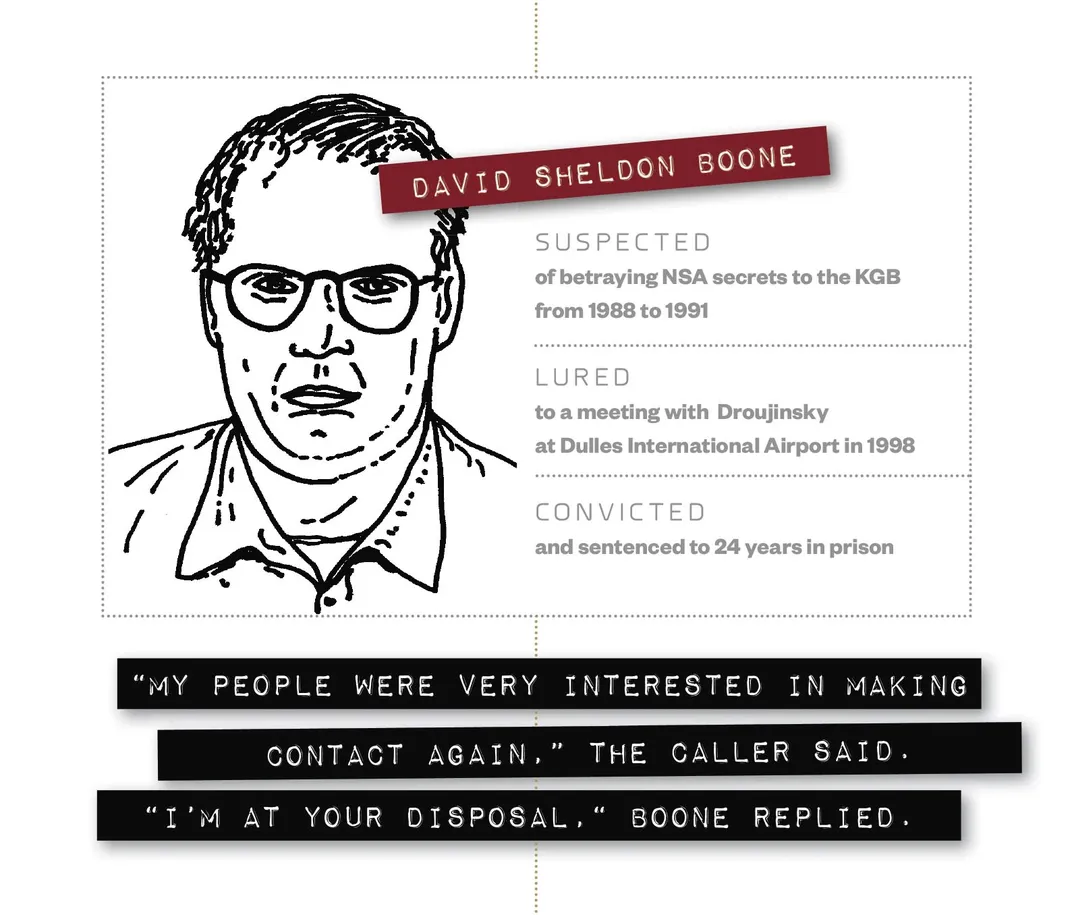

One of the most sensitive breaches Droujinsky dealt with involved David Sheldon Boone, a burly Army signals intelligence analyst assigned to the NSA. Born in Flint, Michigan, in 1952, Boone joined the Army in 1970. While he was detailed to an NSA listening post in Augsburg, Germany, from 1988 to 1991, he passed agency secrets to the KGB in a series of meetings along the Rhine. But it was a decade before U.S. intelligence realized what had gone on. Droujinsky was called in, much like a relief pitcher in a late inning.

From Washington, he called Boone in Germany, using a tricked-out phone that could be traced only to London. “I told him, ‘My people were very interested in making contact again. I’m sure there will be remuneration for your service.’” A plane ticket would be waiting for Boone in Germany and a hotel room in London.

“I’m at your disposal,” Boone replied.

In London Boone made an alarming disclosure: Among the secrets he’d passed to the Soviets were a Top Secret NSA directive revealing the Soviet targets of U.S. nuclear weapons and a manual that served as a handbook for the entire U.S. spy-satellite program. Each of the manual’s 300 pages was marked Top Secret-Umbra, a designation above Top Secret.

The problem was how to lure Boone to Washington, where he could be arrested. “Boone had left the NSA, and when he got out, he married a German woman and moved there,” Droujinsky says. “I said, we’d like you to come to Washington. We’d like to develop another source like you and find out how we did it.” Boone agreed to meet again in a room at a Marriott hotel at Dulles International Airport, outside Washington, in October 1998. This time, FBI agents were waiting.

Droujinsky recalled the scene when Boone knocked on the door and found himself facing a roomful of strangers: “Boone said, ‘Oh, I was looking for somebody else.’ They said, ‘He’s right here.’” As part of the sting, some agents hustled Droujinsky out of the room as he protested, “I’m a diplomat! You can’t do this!”

“They interviewed Boone and asked who was this guy, and Boone said, ‘I was at the bar last night and I just met this guy, and I didn’t know him.’” But everything he’d told Droujinsky in London was on tape. Boone pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 24 years in prison. He is listed as an inmate at the federal prison in Safford, Arizona.

**********

Of course, not everything went according to Droujinsky’s plans. In 1997, a target began a meeting with him by handing him a note that read, “I thought you were an FBI agent trying to set me up.” Droujinsky laughed it off and soon had the target, a former Army paralegal, talking about how he and two friends, fellow student radicals at the University of Wisconsin in the 1970s, had spied for the Stasi in years past. They all ended up in prison. Another target, an M1 Abrams tank instructor known as the Cowboy, agreed to meet Droujinsky at a motel room but came close to knocking an FBI microphone out of its hiding place when he tossed his ten-gallon hat against the draperies. “It must’ve made a huge noise in the headphones of the agents next door,” Droujinsky says. He held his breath, but the microphone stayed in place, and the Cowboy was eventually found guilty of attempted espionage.

One of Droujinsky’s closer calls came in November 1990, when he set up a meeting at Newark International Airport with Jamal Mohamed Warrayat, a Kuwait-born veteran of the U.S. Army Airborne.

Warrayat “decided during the Gulf War to launch a major terrorist attack to help the Iraqis,” Droujinsky says. “He called the Iraqi U.N. mission in New York. We heard it.” This time, Droujinsky posed as an Arabic-speaking American working as a contractor for the Iraqis.

“I had a recorder in my dispatch case on the table,” he says. “I opened the case to get out a pad and pen. Warrayat suddenly stuck his hand in the dispatch case. I slammed it down on his hand.

“‘What are you doing?’” I asked.

“He said, ‘I’ve seen it on television. It might be a recorder in there.’”

Droujinsky assured him that such things happened only on television. Warrayat removed his hand. “He offered me a menu of terrorist acts he was willing to carry out”: assassinating President George H.W. Bush and other American officials, blowing up the George Washington Bridge, planting bombs in the tunnels between Manhattan and New Jersey. But Warrayat was arrested before the month was out, and later sentenced to a year for making terrorist threats.

After a career of deceiving spies and terrorists, Droujinsky left with no regrets about the value of his role-playing. After the Soviet Union collapsed, he says, “I felt great for two reasons. One was that our most formidable enemy was diminished as a threat. Second, I felt very good for the people in the Soviet Union because they got more freedom.”

As for the spies he helped to catch, “They decided to do something bad against our country. I was able to stop them. So I feel good about that,” he says. “Sometimes I feel bad about their families...but not for the people we caught.” But why did so many of them talk to Droujinsky? He cites the secrecy required by betrayal: “Spies are very lonely. They cannot talk to anyone, not even their wives. So when I was able to convince them who I was, they opened up.”

Although Droujinsky took his work very seriously, his sense of humor is never far below the surface. “I am gregarious. I make a lot of friends,” he says. “The trouble is they all end up behind bars.”

Related Reads

Spy: The Inside Story of How the FBI's Robert Hanssen Betrayed America

Life Experiences of a Youth from Palestine (By Dimitry Droujinsky)