In a year when so many of us have struggled with feeling isolated in our homes or apartments, living alone in a 14-by-14-foot cabin perched thousands of feet above the wilderness might not sound enticing. For more than a century, though, across the United States, a few intrepid Americans have sought out those remote towers as not just a job, but a lifestyle. And unlike so many jobs that were long considered “man’s work,” women broke the glass ceiling of fire lookout positions almost as soon as the job was established.

Before American women were granted the right to vote or allowed to have bank accounts in their name, they were trekking into forests alone, manning lookout stations, and helping to save millions of acres of wilderness from wildfires across the country.

“Women have earned their place in the history of forest fire lookouts,” says Dixie Boyle, a longtime lookout and author going into her 34th season. She staffs a tower in the Cibola National Forest in New Mexico’s Manzano Mountains. Men like author Jack Kerouac brought attention to the job when he wrote about the 63 days he spent as a fire lookout in the summer of 1956 in books like The Dharma Bums and Desolation Angels, but it’s women like Hallie Morse Daggett, Helen Dowe and Boyle herself who deserve our attention.

“Those early women paved the way for the rest of us,” says Boyle.

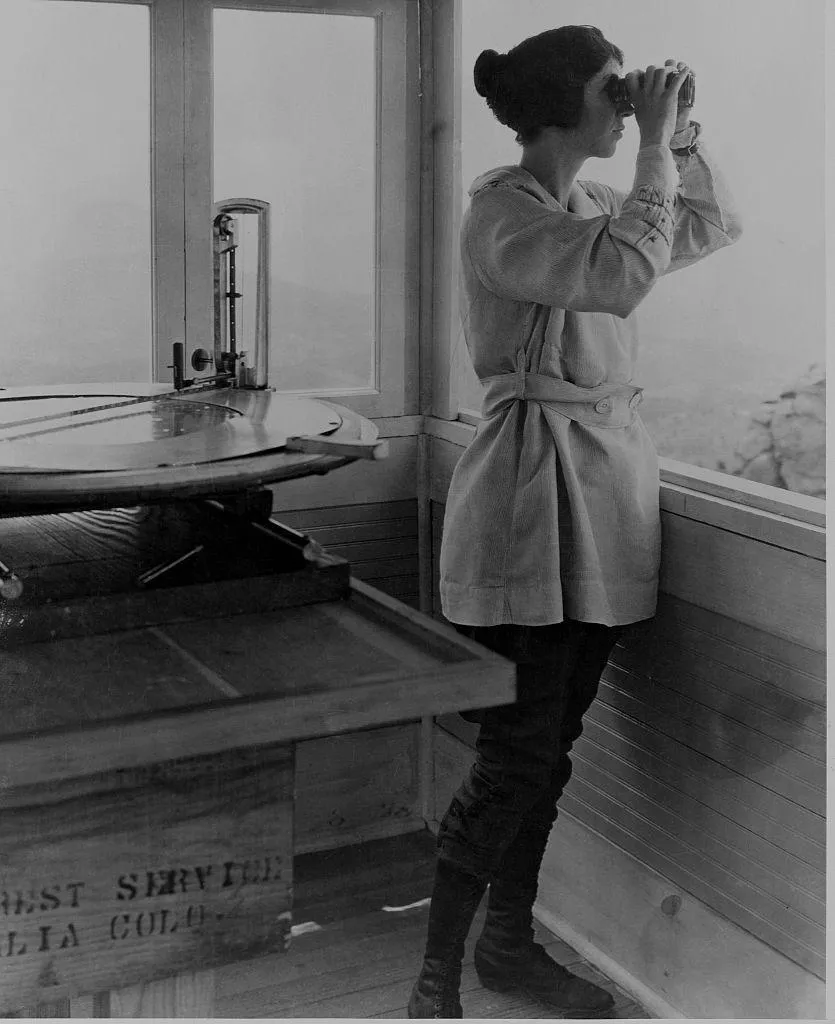

Depending on what part of the country you’re in, fire season generally goes from March or April through September or October. The training for lookouts was, and is, brief. They’re shown how to use the equipment (like the sighting device known as the Osborne Fire Finder), told what duties they’re expected to accomplish to maintain the tower, and sent on their way. After that, it’s up to individual lookouts to haul their equipment to the tower, resupply, and spot and report as many fires as they can throughout the season. It’s not a great job for anyone who needs another soul to motivate them each day. Lookouts are truly on their own.

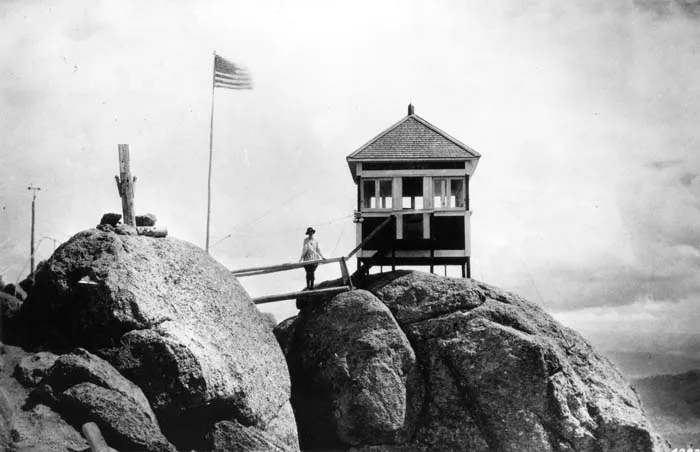

In the decades following the Great Fire of 1910 (aka “the Big Blowup” or “Devil’s Broom fire”), which scorched 3 million acres across Montana, Idaho and parts of Washington, the U.S. Forest Service and state and local agencies created a system of thousands of lookout stations across the country, many of them towers with small cabins (or “cabs”) that were perched on cliffs and peaks, with 360-degree views of the wilderness so lookouts could detect and report smoke before the fires got out of hand. By the 1930s, nearly 5,000 active lookout towers stood across the U.S., but today that number is drastically smaller.

“In 2019, one of our members did a survey and came up with a figure of 450 to 500 [towers],” says Gary Weber of the Forest Fire Lookout Association. “A few years ago, the count of standing towers was somewhere over 2,700, so it's safe to say that there are over 2,000 inactive towers, some of which could be put back into some sort of service, but many are long abandoned.”

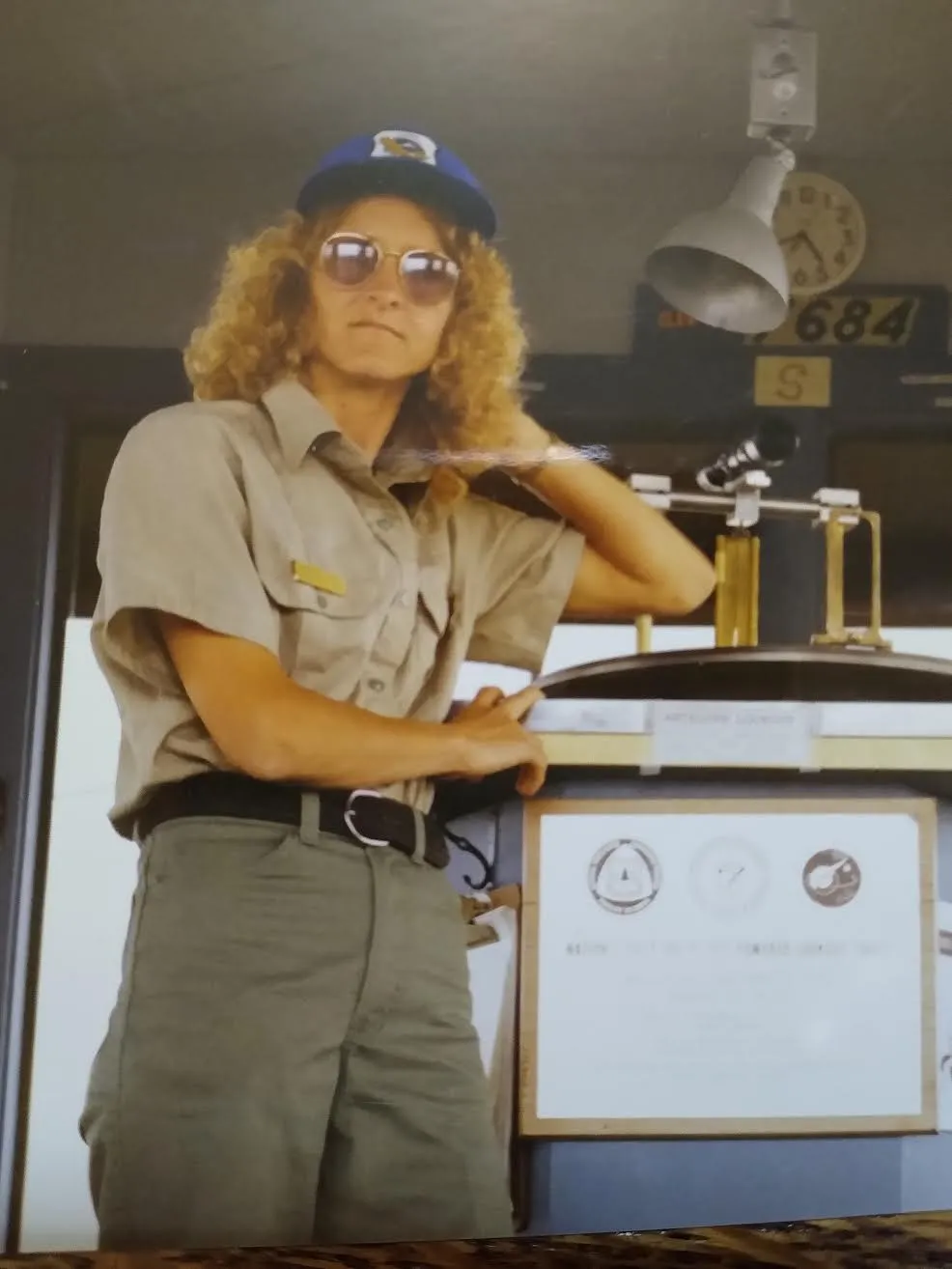

Because so many agencies (Forest Service, National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management and multiple states) are involved with the lookout process, it’s tough to pin down the exact number of fire lookouts, let alone break down the ratio of women to men who are staffing the towers. “I would hazard a guess that it's probably close to 50/50,” says Weber.

In 1902, before the system of lookout towers was established, a woman named Mable Gray, who was a cook at a timber cruising camp in northern Idaho, was asked by her boss to climb a ladder, sit 15 feet up in a fir tree, and look for smoke. If she saw anything suspicious, she’d hop on her horse and alert the crews.

Just three years after the Forest Service created the job, Hallie Morse Daggett became the first female to serve as a Forest Service fire lookout, at Eddy Gulch in northern California’s Klamath National Forest. Before that, women in the Forest Service were pretty much relegated to clerical work. Daggett attended boarding school in San Francisco, far from the wilderness, but she’d grown up fearing the wildfires she saw as a child. She loved exploring nature in the Siskiyou Mountains, and so in 1913, even though no woman had ever held the position, she applied to be a lookout.

Daggett was among the top three candidates for the job, the two others, of course, being men. After seeing Daggett’s application, Ranger M.H. McCarthy wrote a letter to his boss explaining why he thought Daggett would be the best person for the job:

The novelty of the proposition which has been unloaded upon me, and which I am now endeavoring to pass up to you, may perhaps take your breath away, and I hope your heart is strong enough to stand the shock. It is this: One of the most untiring and enthusiastic applicants which I have for the position is Miss Hallie Morse Daggett, a wide-awake woman of 30 years, who knows and has traversed every trail on the Salmon River watershed, and is thoroughly familiar with every foot of the District. She is an ardent advocate of the Forest Service, and seeks the position in evident good faith, and gives her solemn assurance that she will stay with her post faithfully until she is recalled. She is absolutely devoid of the timidity which is ordinarily associated with her sex as she is not afraid of anything that walks, creeps, or flies. She is a perfect lady in every respect, and her qualifications for the position are vouched for by all who know of her aspirations.

Daggett got the job, and her first season she allegedly spotted 40 fires. Only five acres total burned. She made the arduous trek to Eddy Gulch for 15 seasons (lookouts had to haul in supplies by foot or pack mule), blazing a trail for “lady lookouts,” as early news articles dubbed them, and breaking into this role long before women would become smokejumpers, let alone CEOs or vice presidents.

“She thwarted convention,” says Aimee Bissonnette, author of the children’s book Headstrong Hallie! The Story of Hallie Morse Daggett, The First Female “Fire Guard.”

Helen Dowe, an artist for the Denver Times, followed in Daggett’s footsteps in 1919 when she climbed up Devil’s Head lookout in Colorado, a tower that’s perched on a granite outcrop at 9,748 foot elevation. She served until 1921, reporting several fires and, like Daggett, preventing thousands of acres from burning.

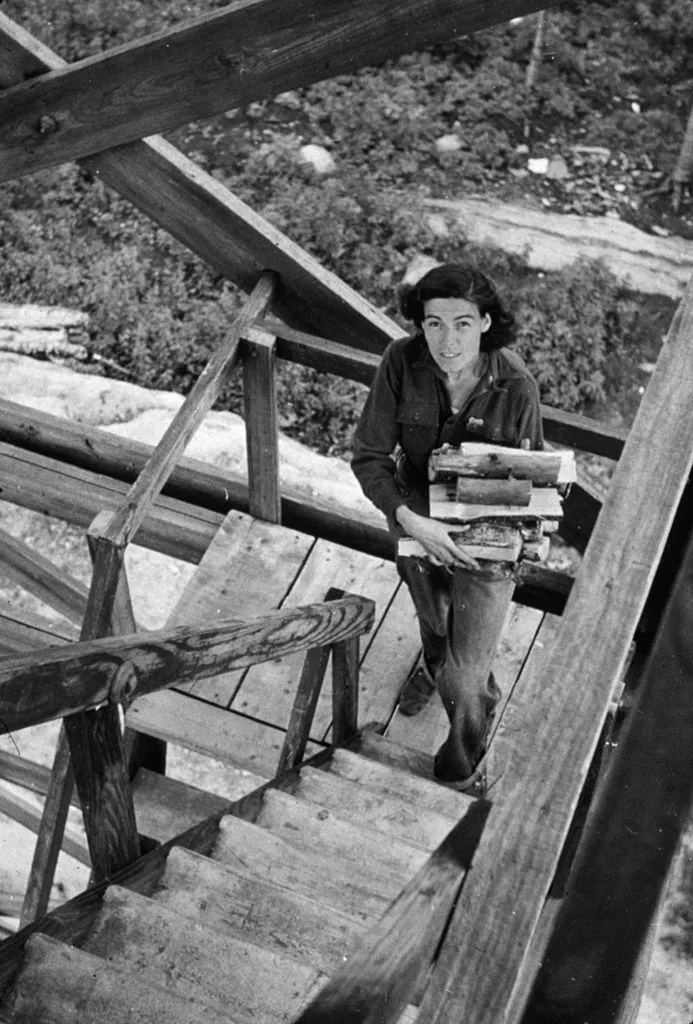

After women like Daggett and Dowe opened the door, the number of female lookouts surged during World War II. Since so many men were overseas, women took to the towers, some filling in for their husbands, and others taking on the position in the same spirit of adventure and independence as Daggett and Dowe. Most lookout positions today that aren’t volunteer pay minimum wage, so the people who take on the job are oftentimes doing it because they love it, and not because of the paycheck.

Any lookout will tell you that there’s much more to the job than sitting in a tower, waiting for a fire. It can be grueling, lonely and, at times, incredibly stressful.

“What a lookout absolutely cannot be is a whiner,” says Kathy Allison, a lookout who has served for over 20 years in Sequoia National Forest and Kings Canyon National Park in California. She created the Buck Rock Foundation, which aims to preserve the tradition of fire lookouts and restore historic towers that have been abandoned. As technology evolves, having a lone person standing watch in a wooden or steel tower is becoming rarer, with satellite technology, livestreaming cameras, drones and planes slowly taking the place of human observation. Many towers across the U.S. have been turned into vacation rentals. Longtime lookouts like Allison believe the job still serves a vital function, and it turns out she’s not alone.

Even as technology threatens to take over the job, agencies have conducted years of research and determined that, for now, a combination of planes and human observation is the most efficient and economical way to spot and fight wildfires. Planes can't really fly during lightning storms, and having aircraft circling hundreds of thousands of acres across the U.S., 24/7 isn't feasible. So trained, dedicated lookouts who can spot smoke or fire and record the location, size and characteristics using binoculars, maps, a compass and the Osborne Fire Finder, and quickly and calmly report those sightings to dispatchers are key in containing wildfires.

“With the exception of a couple years ago when the state of Wisconsin dropped their entire program, there are a few places realizing the value of a human observer, and actually bringing towers back into service,” says Weber of the Forest Fire Lookout Association. “Overall, I'd say that the active towers are holding their own.”

Before Allison knew the history of women like Dowe and Daggett, she grew up watching the social unrest of the 1960s on her parents’ black-and-white television. “Gloria Steinem became my hero,” she says. Allison got a degree in history and met and married a “charismatic wild man” who was surveying peregrine falcons in California’s Kings Canyon. When her husband was killed in an airplane crash, Allison needed a job, fast. A friend told her about an opening for a lookout, and she took it.

“I needed solitude,” Allison says. “I grew to love it. It was exactly what I needed.”

Allison says that lookouts have to be completely self-sufficient, maintaining the tower by scraping paint or repairing damage from storms, gathering and splitting wood, hauling water, planting gardens, caulking windows and doing their “business” in outhouses, which they also have to maintain. “If the wind blows 75 miles per hour, we literally batten down the hatches and do what we can to protect the tower and pray we don't get blown off the catwalk,” she says.

Feeling like she had to prove herself to a few skeptical male counterparts over the years was one of the more unpleasant parts of the job, says Allison. “There is sexism in every aspect of our society, but maybe a little more with the old-school forest service people,” she says. “There were times I felt disrespected by men who were driven by power or ego. Once I proved my mettle, though, it was OK.”

Philip Connors is a longtime lookout in New Mexico’s Gila National Forest and the author of Fire Season: Field Notes From a Wilderness Lookout. Like Allison, he’s vocal about the need for lookouts, even as technology encroaches. He’s also vocal about the role of women in the job. “In the Gila National Forest, where I work, women are the backbone of the lookout program,” he says.

Sara Irving, who is going into her 40th season as a lookout in a tower (originally built in 1923 and reconstructed in 1948) at Mogollon Baldy in the Gila wilderness, is one of those women. The Gila has 10 lookouts that are staffed each season, and two that are not in operation. Irving makes the 12-mile hike to the cabin each year, traversing a high crest along the Mogollon Mountains that ranges in altitude from 9,000 to 10,000 feet. The region is home to rattlesnakes, elk, jaguars and black bears—creatures that become part of everyday life for many lookouts across the wilderness.

“People romanticize the job somewhat, but it can be pretty stressful,” Irving says. She’s been evacuated from her tower by helicopter due to encroaching flames, and lookouts have to make quick, informed decisions in a split second. Decisions that could impact not just acres of wilderness, but the lives of firefighters on the ground and in the air.

Rebecca Holcomb made those life-or-death decisions from her perch at Anthony Peak lookout in the Mendocino National Forest in northern California—at times while cradling her 4-month-old son in the cabin. Holcomb decided she wanted to work for the Forest Service as a kid when she saw a ranger fighting a fire in an episode of the show “Lassie.” Over the years she braved lightning strikes to the tower, hauled water and food up the endless, steep steps to the tower, and made it through nights where she’d listen to strange sounds coming from below, only to wake up to see bear prints on the stairs to the trap door leading to the cabin where she and her young son slept. Luckily, she’d remembered to lock the trap door.

Despite the tough moments, Holcomb, who says she’s considered a “short timer” since she has served for five seasons over the years, loves the lookout life, surrounded by nature, enveloped in solitude, and doing a job that’s crucial to preserving what’s left of the American wilderness. For many lookouts, it’s that solitude that keeps luring them back to the tower.

“The clouds and lightning storms are magical,” says Irving of her perch at Mogollon Baldy. “I watch the sky and the light change all day long, and I get paid for doing it. That’s a gift.”

That gift comes in large part from women like Hallie Daggett and Helen Morse, who climbed the towers and searched for smoke long before Gloria Steinem or the women’s movement or the fight for equal pay.

Carol Henson, who spent 29 years working for the U.S. Forest Service, has spent “thousands of hours” researching women in wildland firefighting. “Look at the women who aren’t talked about,” she says, meaning the pioneer women who built houses and farmed or jumped in to help when there were prairie fires, long before lookout towers were built. “As women, we don’t celebrate our own history enough.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/97/1e/971e3074-c3be-4e04-8b1b-896b1a7e1483/lady_lookout-mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/c4/54c451a0-a629-4b71-b817-0eef1c112789/lady_lookout-social.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Dina-Gachman-bio-photo.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Dina-Gachman-bio-photo.jpg)