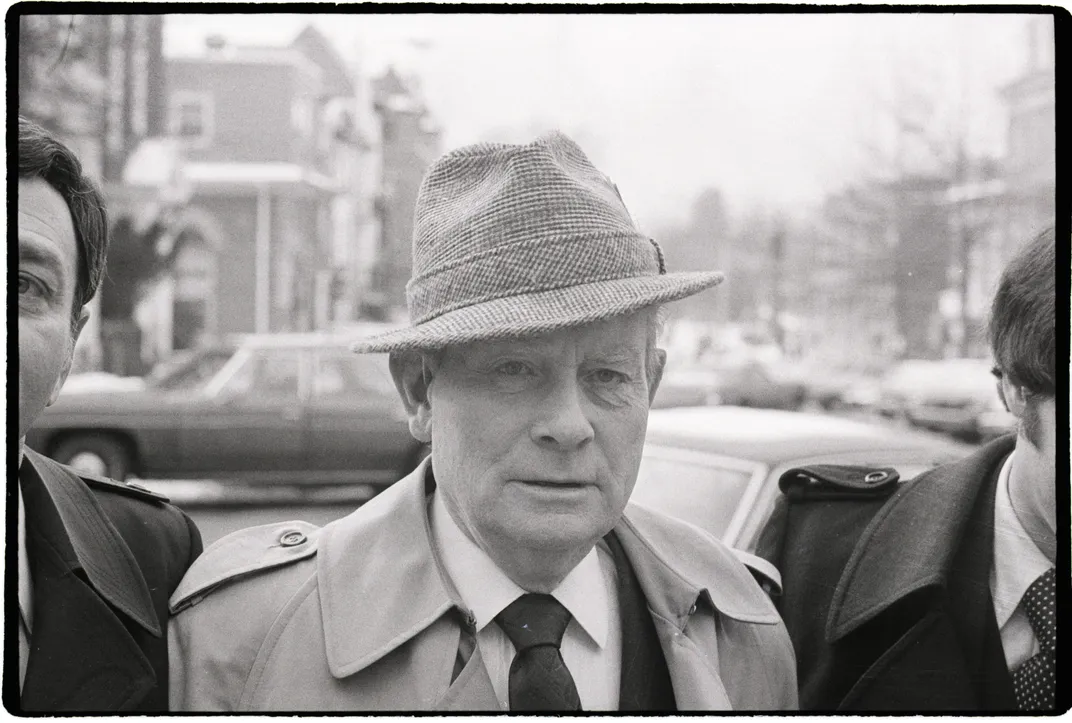

Fifty Years Ago, the Murder of Jock Yablonski Shocked the Labor Movement

The conspiracy to kill the United Mine Workers official went all the way to the top of his own union

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/88/60/8860f294-e7a8-497c-bfb7-650f6b28e0f6/gettyimages-515103874.jpg)

On New Year’s Eve, 1969, Chip Yablonski called his father. Or at least, he tried to.

“The phone didn’t answer,” Yablonski recalled nearly a half-century later. “We thought [he] went out for the evening.”

Yablonski, at the time an attorney in Washington, D.C., didn’t think anything of it until a few days later, when his father, United Mine Workers (UMW) leader Joseph “Jock” Yablonski, didn’t show up for a swearing-in of elected officials in Washington, Pennsylvania, a small city about a half-hour south of Pittsburgh. Chip and his brother, Ken, had feared for their father’s safety since he announced the previous May that he would challenge W.A. “Tony” Boyle for the UMW presidency. He’d lost the election earlier that month but was challenging the results as fraudulent.

Ken, who lived in Washington, went to check on his father in his farmhouse in Clarksville, about 20 miles away in the heart of southwestern Pennsylvania’s coal country, where he found the results of a grisly execution.

Jock Yablonski was dead, as was his wife, Margaret, and their 25-year-old daughter, Charlotte. All had been murdered by gunshot. His dad’s Chevrolet and sister’s Ford Mustang had their tires slashed, and the phone lines to the house had been cut.

Even in the early stages of the investigation into the triple homicide, authorities believed that more than one person was involved. But investigators ultimately uncovered a conspiracy that stretched all the way to Boyle himself, and the ensuing criminal cases would lead to the UMW and to the labor movement overall changing how they operated.

“After Boyle was arrested, you have this moment when [the UMW] opens up, and it’s a critical moment,” says labor historian Erik Loomis. “In many ways, the modern leadership of the [UMW] comes out of that movement.”

*****

Reform—if not revolution—flowered in the 1960s and that extended to the maturing labor movement. The first generation of organizers was retiring, including John L. Lewis, who had spent more than 40 years as president of the UMW, which he called the “shock troops of the American labor movement.”

Lewis was a transformational figure in the American labor movement, founding the Congress of Industrial Organizations (the CIO, which later merged with the AFL) and serving as its first president from his offices in Washington, D.C. Lewis encouraged the growth of unionization nationwide, but was also an autocrat, purging anyone that disagreed with him. In fact, that’s how Jock Yablonski rose to prominence within the union.

Born in Pittsburgh in 1910, Yablonski went to work in the coal mines of southwestern Pennsylvania at the age of 15. A mine explosion killed his father in 1933, and for years after, mine safety was a key issue to him. Yablonski caught Lewis’ eye and soon received the titan’s backing: first to run for executive board in 1941 and then the following year for president of the district encompassing his home region of Pennsylvania. (Incumbent district president Patrick Fagan had drawn Lewis’ ire for supporting Franklin Roosevelt’s bid for a third term; Lewis favored Republican candidate Wendell Willkie.)

In 1960, Lewis retired and was succeeded as union president by Thomas Kennedy, but the real power behind the throne was Boyle, the vice president, who rose through the ranks in his native Montana before being brought to Washington by Lewis to be groomed as his true heir apparent. As Kennedy’s health failed, Boyle took over executive duties, and finally became president upon Kennedy’s death in 1963. Boyle shared Lewis’ dictatorial tendencies, but none of his acumen.

“Tony Boyle operated the United Mine Workers like John Lewis did, but he was not John Lewis, and did not achieve what he had,” says Chip Yablonski, now 78 years old and retired from his law practice. “It was a corrupt institution from top to bottom.”

The by-laws of the union stated that retirees retained full voting benefits, and Boyle had maintained power with what the younger Yablonski calls “bogus locals,” full of retirees and not necessarily enough representation of active members. Boyle also seemed to find high-paying jobs within the union for family members.

When Boyle spent lavishly on the union’s 1964 convention in Miami—the first outside of coal country, he met with opposition among the UMW. “If you try to take this gavel from me,” Boyle was quoted by United Press International as saying, “I’ll still be holding it when I’m flying over your heads.” In Miami, a group of miners from District 19, which encompassed Kentucky and Tennessee, physically assaulted anti-Boyle speakers.

The union also owned the National Bank of Washington (D.C., not Pennsylvania), a unique arrangement that had helped the union expand and purchase their own mines in fatter times, but by the 1960s had become rife with fraud and poor management. For years, the union improved the bank’s finances at the expense of union members’ benefits, a scheme that wouldn’t be exposed until later in the decade.

On top of that, Boyle had become too cozy with the mine owners, as evidenced by his tepid reaction to the Farmington mine disaster in West Virginia. Early on the morning of November 20, 1968, a series of explosions rocked the region. Of the 95 men working the overnight “cat eye” shift, 78 were killed. The remains of 19 remained in the shaft, which would be sealed off 10 days later with no input from miners’ families Boyle called it “an unfortunate accident,” praised the company’s safety record and didn’t even meet with the miners’ widows.

Jock Yablonski, meanwhile, was an unlikely revolutionary. In his 50s, he was part of the inner circle running the union, but he saw the problems within the union’s operation and was outspoken about it. “He’s no radical,” Loomis says of Yablonski. “He’s an insider, but he recognized what was happening among the rank and file, and the union wasn’t really serving its members well.”

Boyle had Yablonski removed from his position as district president in 1965, ostensibly for insubordination. But Yablonski’s son Chip saw another reason.

“Boyle saw my dad as a threat,” recalls Chip. “[My dad] stewed for a few years and decided to challenge Boyle [in May 1969].”

“From the moment he announced his candidacy, we were afraid goons from District 19 would be activated,” says Chip.

And that’s exactly what happened. After the murders, the criminal warrant from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania stated that Boyle went to Albert Pass, a Boyle loyalist and president of District 19, and said, “Yablonski ought to be killed or done away with.” Shortly thereafter, District 19 received $20,000 for a research fund from the union. Checks were cut to retirees, who cashed them and kicked them back to Pass, who then used the money as payment to order the murder of Yablonski.

At the same time, the union newspaper, the Mine Workers’ Journal, became a house organ for Boyle during the campaign, publishing anti-Yablonski propaganda. Boyle had an additional 100,000 ballots printed up to stuff the ballot box and on Thanksgiving, two weeks before the election, Pass told Boyle the vote totals from District 19. Of course, Boyle won the district decisively, and just as unsurprisingly, he won the election.

Through it all, Yablonski and his attorneys beseeched the U.S. Department of Labor to get involved, to no avail. “The Department of Labor had no interest in investigating,” says the younger Yablonski. “The entire process was riddled with fraud. It was a flawed process from beginning to end. It had reversible error all through it.”

It took the murder of his father, mother and sister for the federal government to step in.

*****

The shocking brutality of the murders soon gave way to the startling ineptitude of the crime and cover-up. Within a month, federal investigators discovered the embezzlement to pay for the assassins, who were quickly arrested in Cleveland. A vital clue was a pad in Yablonski’s home with an Ohio license plate number on it. Apparently, the killers had been stalking him for some time – even missing several occasions to kill him when he was alone.

Silous Huddleston, a retired miner in District 19, enlisted his son-in-law Paul Gilly, charitably described as a house painter, for the job. He, in turn, roped in Claude Vealey and Buddy Martin, two other itinerant criminals. There wasn’t a high school diploma between the three of them.

Like most people in Pennsylvania, attorney Richard Sprague read about the murders and the initial arrests in the newspaper. But he was about to become intimately involved. Washington County, like many less populous counties in Pennsylvania at the time, only had a part-time district attorney. Washington County’s D.A., Jess Costa, knew the case would be far bigger than anything he’d ever handled so he asked Sprague, who worked for future U.S. senator Arlen Specter in Philadelphia, to be special prosecutor.

Sprague brought to bear an investigation that was already shaping up to be one of the largest in state history, with local law enforcement working with the Pennsylvania State Police and FBI. “All the law enforcement agencies worked like a clock,” says Sprague, who at 94 still comes to work daily at the Philadelphia law practice he founded. “There was no jealousy.”

Ultimately, the prosecution reached Boyle, who in a moment of bittersweet satisfaction, was arrested for the murders in 1973 while he was being deposed in a related civil lawsuit by Chip Yablonski. By then, Boyle had already been convicted of embezzlement, and the following year, he was convicted of murder, one of nine people to go to prison for the Yablonski killings.

“It was really a feeling of total satisfaction that justice had fought its way through,” Sprague says. “It was a long, long road.”

The road would be just as long – and the satisfaction short-lived – to reform the union.

*****

When news broke of Yablonski’s murder, thousands of miners in western Pennsylvania and West Virginia walked off the job. Before his death, he was a reformer. Now he was a martyr to the cause.

In April 1970, Miners for Democracy was formed to continue the reform efforts with Yablonski’s campaign – and also to continue Yablonski’s efforts to have the 1969 election invalidated. Ultimately, a judge threw out those election results and set new elections in 1972. This time, Boyle was challenged by (and lost to) Arnold Miller, a West Virginia miner whose diagnosis of black lung disease led to him becoming an advocate for miners stricken by the disease.

The year after Miller’s election, the union – with Chip Yablonski as its general counsel – rewrote its constitution, restoring autonomy to the districts and eliminating the bogus locals Boyle had used to consolidate power. But the district leaders weren’t as reform-minded as the staff, many of whom were taken from the Miners for Democracy movement, and worse yet, Miller was ill and ineffectual as president. “A lot of movements in the 1970s thought more democracy would get a better outcome, but that isn’t the case, because some people aren’t prepared to lead,” Loomis says.

The labor landscape is vastly different than it was at the time of Yablonski’s assassination. The nation has moved away from manufacturing and unionized workforces. Twenty-eight states have right-to-work laws that weaken the power of unions to organize. In 1983, union membership stood at 20.1 percent of the U.S. workforce; today it’s at 10.5 percent.

That, coupled with the decline of coal use,and the rise of more efficient and less labor-intensive methods of extracting coal, has led to a decline in the coal mining workforce. “The UMW is a shell of its former self, but it’s not its fault,” Loomis says. “I’m skeptical history would have turned out differently” if Yablonski himself had made changes.

Chip Yablonski believes his father would have served just one term had he survived and become UMW president. But in death, Yablonski’s legacy and the movement his death helped inspire, lives on. Richard Trumka, who like Yablonski was a coal miner in southwestern Pennsylvania, came out of the Miners for Democracy movement to follow the same path as John L. Lewis, serving as UMW president before being elected president of the AFL-CIO, a role he still holds today.

“[Trumka] helped restore things to the way they should have been,” Yablonski says.