Finding King Herod’s Tomb

After a 35-year search, an Israeli archaeologist is certain he has solved the mystery of the biblical figure’s final resting place

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Herodium-631.jpg)

Shielding my eyes from the glare of the morning sun, I look toward the horizon and the small mountain that is my destination: Herodium, site of the fortified palace of King Herod the Great. I'm about seven miles south of Jerusalem, not far from the birthplace of the biblical prophet Amos, who declared: "Let justice stream forth like water." Herod's reign over Judea from 37 to 4 B.C. is not remembered for justice but for its indiscriminate cruelty. His most notorious act was the murder of all male infants in Bethlehem to prevent the fulfillment of a prophecy heralding the birth of the Messiah. There is no record of the decree other than the Gospel of Matthew, and biblical scholars debate whether it actually took place, but the story is in keeping with a man who arranged the murders of, among others, three of his own sons and a beloved wife.

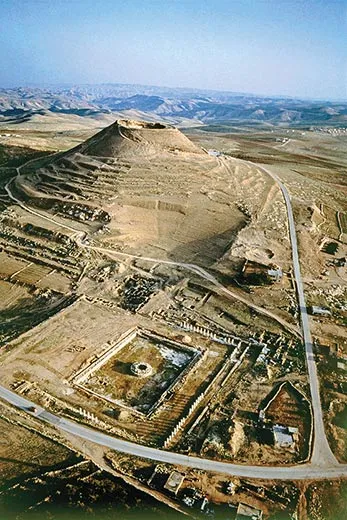

Long an object of scholarly as well as popular fascination, Herodium, also called Herodion, was first positively identified in 1838 by the American scholar Edward Robinson, who had a knack for locating biblical landmarks. After scaling the mountain and comparing his observations with those of the first century Jewish-Roman historian Flavius Josephus, Robinson concluded that "all these particulars...leave scarcely a doubt, that this was Herodium, where the [Judean] tyrant sought his last repose." Robinson's observation was confirmed later that century by Conrad Schick, the famous German architect and archaeologist who conducted extensive surveys of Jerusalem and its nearby sites.

But where precisely was the king entombed? At the summit of Herodium? At the base? Inside the mountain itself? Josephus didn't say. By the late 1800s, Herod's tomb had become one of biblical archaeology's most sought-after prizes. And for more than a century archaeologists scoured the site. Finally, in 2007, Ehud Netzer of Hebrew University announced that after 35 years of archaeological work he had found Herod's resting place. The news made headlines worldwide—"A New Discovery May Solve the Mystery of the Bible's Bloodiest Tyrant," trumpeted the London Daily Mail.

"In terms of size, quality of decoration and prominence of its position, it's hard to reach any other conclusion," says Jodi Magness, an archaeologist in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who has excavated at other sites where Herod oversaw construction projects. Ken Holum, a University of Maryland archaeologist and historian who served as a curator for the traveling Smithsonian exhibition "King Herod's Dream," cautions that "it is always wise to be less than certain when there is no identifying inscription or other explicit identification." But he says he personally believes Netzer has indeed discovered Herod's tomb.

Netzer, 75, is one of Israel's best-known archaeologists and a renowned authority on Herod. Trained as an architect, he worked as an assistant to the archaeologist Yigael Yadin, who from 1963 to 1965 led an exhaustive dig at Masada, the fortified plateau near the Dead Sea where Herod built two palaces. In 1976, Netzer led a team that discovered the site of one of Herod's infamous misdeeds: the murder of his young brother-in-law, Aristobulus, whom Herod ordered to be drowned in a pool at his winter palace complex near Jericho. Yet the discovery of Herod's tomb would be Netzer's most celebrated find. And as is often the case with such discoveries, Netzer found it where, for years, he least expected it.

Arriving at Herodium, which is not only an active archaeological site but also, since the late 1960s, a national park, I drive partway up the mountain to the parking lot where I will meet Netzer. In the early 1980s, before the first intifada turned the West Bank into a conflict zone, Herodium drew some 250,000 people per year. For the moment I'm the sole visitor. At a kiosk I buy a ticket that lets me ascend on foot to the summit. At the base of the mountain the remains of a royal complex, known as Lower Herodium, sprawl across nearly 40 acres. Gone are the homes, gardens and stables; the most recognizable structure is an immense pool, 220 by 150 feet, which is graced with a center island.

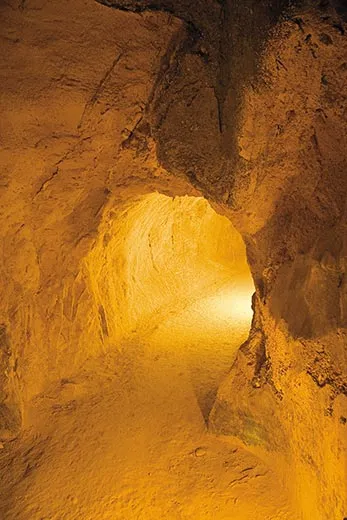

A narrow trail hugging the hillside leads me to an opening in the slope, where I enter an enormous cistern now part of a route to the summit, more than 300 feet above the surrounding countryside. The air inside is pleasantly cool, and the walls are smooth and dry, with patches of original plaster. I follow a network of tunnels dug during the second Jewish revolt against the Romans in A.D. 135 and enter another, smaller cistern. Daylight pours in. I climb a steep staircase and emerge at the summit, in the middle of the palace courtyard.

The palace fortress once reached close to 100 feet high and was surrounded by double concentric walls accented by four cardinal point towers. Besides living quarters, the upper palace had a triclinium (a Greco-Roman-style formal dining room lined on three sides by a couch) and a bathhouse that features a domed, hewn-stone ceiling with an oculus (round opening). It's strange to find such a perfectly preserved structure amid the ancient ruins, and it leaves me with an eerie sense of standing both in the past and the present.

Gazing out from the perimeter wall, I see Arab villages and Israeli settlements in three directions. But to the east cultivation abruptly stops as the desert exerts its authority, plummeting out of sight to the Dead Sea, then rising again as the mountains of Jordan. Why would Herod build such a prominent fortress—the largest palace complex in the Roman world—on the edge of a desert?

Though the site had little apparent strategic value, it held profound meaning for Herod. Born around 73 B.C., he was the governor of Galilee when, in 40 B.C., the Parthian Empire conquered Judea (then under Roman control) and named a new king, Mattathias Antigonus. Herod, probably more shrewd than loyal, declared allegiance to Rome and fled Jerusalem with as many as 5,000 people—his family and a contingent of fighting men—under cover of night.

Surging over rocky terrain, the wagon in which Herod's mother was riding overturned. Herod drew his sword and was on the verge of suicide when he saw she had survived. He returned to the battle and fought "not like one that was in distress...but like one that was excellently prepared for war," Josephus wrote. In tribute to his victory and his mother's survival, he vowed to be buried there.

Herod sought refuge in Petra (in today's Jordan)—capital of the Nabateans, his mother's people—before heading to Rome. Three years later, with Rome's backing, Herod conquered Jerusalem and became king of Judea. A decade would pass before he would begin work on the remote fortified palace that would fulfill his pledge.

Herod must have given a lot of thought to how Herodium would function, given the lack of a reliable water source and the mountain's distance from Jerusalem (in those days, a three- to four-hour trip by horseback). He arranged for spring water to be brought three and a half miles via an aqueduct, relocated the district capital to Herodium (with all the staff that such a move implied) and surrounded himself with 10 to 20 trustworthy families.

"Herodium was built to solve the problem he himself created by making a commitment to be buried in the desert," says Netzer. "The solution was to build a large palace, a country club—a place of enjoyment and pleasure." The summit palace could be seen by Herod's subjects in Jerusalem, while the tallest of the four towers offered the king pleasant breezes and a gripping view of his domain.

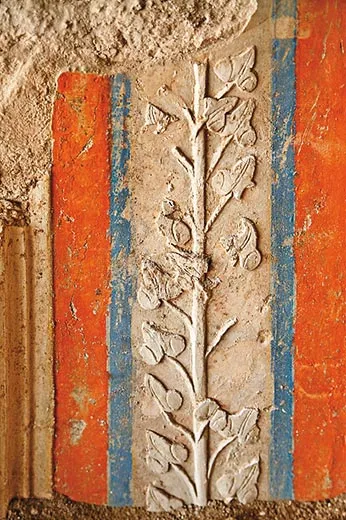

Ongoing excavations by Netzer reveal the impressive variety of facilities that Herod built at his desert retreat, including a royal theater that accommodated some 450 spectators. Netzer believes it was constructed to entertain Marcus Agrippa, Rome's second in command and a close friend of the Judean king, who visited Herodium in 15 B.C. Netzer unlocks a plywood door that has been installed on the site and invites me into the royal box, where Herod and his honored guests would have been seated. The walls were decorated with vivid secco landscape paintings (colors applied to dry, not wet, plaster). The colors, though subdued now, still feel vibrant, and we gaze at the image of an animal, maybe a gazelle, loping along.

Around 10 B.C., according to Netzer, Herod oversaw the construction of his mausoleum. Upon its completion, he undertook the final stage of his self-commemoration by literally increasing the mountain's height: Herod's crew carted gravelly soil and rocks from the surrounding area to Herodium, pouring it all around the summit. Even with unlimited manpower, it must have been a Sisyphean enterprise to pile all that earth some 65 feet high and comb it over the original slopes like a child's carefully smoothed sand hill. "Like a pyramid," Netzer says, "the entire mountain was turned into a monument."

The borders of Judea were quiet during Herod's reign, enabling him to undertake an ambitious building program that brought employment and prosperity to the region. The major projects he completed include the incomparable Temple in Jerusalem, a stunning winter palace in Jericho, two palaces atop Masada and the harbor at Caesarea. A palace garden in Jericho was elevated so that people strolling along the colonnades would see the foliage and flowers at eye level.

Still, Herod's reign is remembered more for its ruthlessness and paranoia than its architectural feats. He tortured and killed family members, servants and bodyguards, to say nothing of his real enemies. In an Othello-like rage, Herod even ordered the execution of the woman he loved most—his second wife, Mariamne—believing that she had committed adultery. Herod's eldest son and heir apparent, Antipater, convinced the king that two of his other sons were plotting against him—so Herod had them executed. And when Herod learned that Antipater was planning to poison him, he rose from his bed just five days before he died to order the murder of Antipater. (As the Roman Emperor Augustus supposedly quipped: "It's better to be Herod's pig than his son.") In a final act of depravity, Herod imprisoned all the notables of Judea, ordering that they be executed on the day of his death so the country would be plunged into mourning. But when Herod died, in Jericho at about age 69—probably of kidney failure exacerbated by a genital infection, according to Aryeh Kasher's recent biography King Herod: A Persecuted Persecutor—the prisoners were released. Instead of mourning, rejoicing filled the land.

Josephus wrote that Herod's body was conveyed to Herodium, "where, in accordance with the directions of the deceased, it was interred." The late king was "covered with purple; and a diadem was put upon his head, and a crown of gold above it, and a scepter in his right hand."

And so began a mystery that tantalized scholars for centuries.

In the 1860s, Felicien de Saulcy, a French explorer, searched for Herod's tomb on the island in the center of the vast pool in Lower Herodium. Father Virgilio Corbo led an excavation at the summit from 1963 to 1967 on behalf of the Franciscan Faculty of Biblical Sciences and Archaeology in Rome. In 1983, a team led by Lambert Dolphin, a Silicon Valley geophysicist, used sonar and rock-penetrating radar to identify what Dolphin thought was a burial chamber inside the base of the highest tower on the mountaintop.

Netzer, however, did not find Dolphin's data convincing enough to redirect his efforts from other, more promising sites—notably a monumental building in the lower complex. Moreover, Netzer and others argue that entombment in the tower would have been unthinkable, because Jewish law proscribed burial within a living space. Barbara Burrell, a classics professor at the University of Cincinnati, wrote in 1999 that interring Herod inside the palace "would have horrified both Romans and Jews, neither of whom dined with their dead."

Netzer smiles as he recalls that when he investigated the cisterns and tunnels within Herodium in the early 1970s, he was actually standing less than ten feet from the tomb, which he later found halfway up the eastern slope. But Netzer instead continued to focus his attention on the foot of the mountain. "We kept getting hotter and hotter," says Ya'akov Kalman, one of Netzer's longtime associates, "but nothing came of it." Netzer believes that Herod originally intended to be buried in the lower complex, but for unknown reasons changed his mind and chose this other location. In 2005, having completed his work at Lower Herodium without revealing a burial chamber, Netzer turned once again to the mountain.

In April 2007, his team discovered hundreds of red limestone fragments buried in the mountainside. Many bore delicate rosettes—a motif common to Jewish ossuaries and some sarcophagi of the era. Reassembling some of the pieces, Netzer concluded they were all that remained of a sarcophagus more than eight feet long with a gabled cover. The high quality of the craftsmanship suggested the sarcophagus was fit for a king. Plus, the extent of the fragmentation suggested that people had deliberately smashed it—a plausible outcome for the hated monarch's resting place. Based on coins and other items found nearby, Netzer surmises that the desecration occurred during the first Jewish revolt against the Romans, from A.D. 66 to 73. (As Kasher notes in his biography, "Herod the Great" was, for the Jews, an ironic title, designating an arrogant monarch who scorned the religious laws of his own people.)

Within two weeks of finding the rosette fragments, workers unearthed the remains of two white limestone sarcophagi strewn about the tomb. Netzer believes one could have held Herod's fourth wife, Malthace, mother of his son Archelaus. The third sarcophagus might be that of Archelaus' second wife, who, based on the accounts of Josephus, was likely named Glaphyra. Workers also found a few bone fragments at the tomb site, though Netzer is skeptical that an analysis of the scant remains will yield any meaningful information about the identities of those buried at Herodium.

Netzer acknowledges that absent further evidence, the rosette-decorated sarcophagus cannot be definitively assigned to Herod. Duane Roller, professor emeritus of Greek and Latin at Ohio State University and author of the 1998 book The Building Program of Herod the Great, concedes that the tomb belonged to someone of noble lineage, but is convinced that Herod's burial site is at the base of the summit tower. For one thing, Roller notes its similarity to other tombs built in Italy at that time. The lack of an inscription particularly troubles some scholars. David Jacobson, a researcher affiliated with University College London and the Palestine Exploration Fund, suggests that a sarcophagus of a very important personage would have been inscribed, and he points to that of Queen Helena of Adiabene, which was recovered from her royal mausoleum in Jerusalem. But others, including Netzer, point out that it was not common for Jews of that era to inscribe sarcophagi. Besides, it's plausible that Herodium itself was the inscription; the entire edifice declares, "Behold me!"

Clad in work shorts, hiking shoes and a well-worn leather Australian bush hat, Netzer scampers up the path to the tomb site. The septuagenarian offers me a hand as I seek a toehold. He greets the crew in Hebrew and Arabic as we pass from one section, where workers wield pickaxes, to another, where a young architect sketches decorative elements.

The tomb site is nearly barren, but the podium that bore the royal sarcophagus hints at magnificence. It is set into the stony earth, partially exposed and unmarred, the joints between the smooth white ashlars (slabs of square stone) so fine as to suggest they were cut by a machine. Netzer has also found the corner pilasters (columns partially built into the walls), enabling him to estimate that the mausoleum, nestled against the side of the mountain, stood on a base 30 by 30 feet and was some 80 feet high—as tall as a seven-story building. It was built of a whitish limestone called meleke (Arabic for "royal") that was also used in Jerusalem and in the nearby Tomb of Absalom—named after the rebellious son of King David, but likely the tomb of the Judean King Alexander Jannaeus.

The mausoleum's design is similar to the Tomb of Absalom, which dates to the first century B.C. and is notable for its conical roof, a motif also seen at Petra. The remnants of the mausoleum's facade are composed of the three elements of classical entablature: architraves (ornamental beams that sit atop columns), friezes (horizontal bands above the architraves) and cornices (crown molding found on the top of buildings). Netzer has also found pieces of five decorative urns. The urn was a funerary motif, used notably at Petra.

Despite the work still to be done—excavating, assembling, publishing the data—Netzer is clearly gratified by what he has learned, which is, he says, the "secret" of Herodium: how Herod found a way to keep his vow and be buried in the desert. "In my field, ancient archaeology, you could say that once circumstances give me the opportunity to be quite certain, it's not in my character to have further doubts."

Barbara Kreiger is the author of The Dead Sea and teaches creative writing at Dartmouth College.