Five Rescuers of Those Threatened by the Holocaust

Righteous good Samaritans came from across the world to save Jews and others from concentration camps

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Charles-Carl-Lutz-631.jpg)

As persecution of Jews in Europe mounted in the years prior to and during World War II, many people desperately sought visas to escape the Nazi regime. Diplomats, consuls and foreign officials were in a unique position to extend significant help to Jews and other refugees seeking asylum in other countries. But too often the stated policy of foreign governments to stay neutral or restrict immigration left many to perish in Holocaust. As official representatives of their governments, diplomats were obliged to uphold the policies of their countries. Those who acted contrary put themselves at peril. Yet scores of diplomats and others disobeyed their governments by issuing visas, protective papers and other documentation that allowed refugees to escape during the period 1933-1945. Some rescuers established safe houses or hid Jews in their embassies or private residences. When found to be violating their governments' policies, some diplomats were transferred, fired or stripped of their ranks and pensions. When caught by Nazi authorities, they faced imprisonment, deportation to a concentration camp and sometimes murder. But because of their heroic deeds, tens of thousands of lives were saved.

Research assistance and photographs of the featured rescuers has been provided by Eric Saul, author of the upcoming book, Visas for Life: The Righteous and Honorable Diplomats. Saul's many exhibitions on the subject of diplomatic rescues have travelled worldwide.

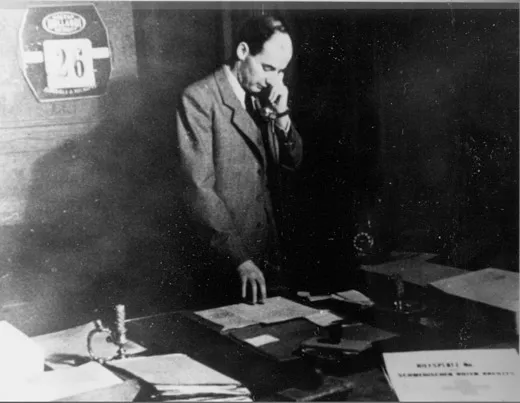

Chiune Sugihara (1900-1986) was posted to Lithuania, in November 1939 as the Japanese consul general. After the Soviets occupied Lithuania in June 1940 and began their massive arrests, Sugihara realized the urgency of the situation and issued an estimated 6,000 transit visas in July and August mainly to Polish Jews stranded in Lithuania. He granted visas for transit through Kobe, Japan, providing an eastern escape route. From Japan, refugees could go to the United States, Canada, South America, or Australia. About 1,000 Sugihara visa recipients from Lithuania survived the war in Shanghai. Even after his government cabled him to restrict his issuance of visas, he continued to do so at a rapid pace. "There was no place else for them to go," he said later. "If I had waited any longer, even if permission came, it might have been too late." He was transferred to Prague in September 1940 and in 1944 arrested by the Soviets and held 18 months. When he returned to Japan in 1947, he was asked to retire, which he said he believed was for his actions in Lithuania. In 1985, Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem, honored Sugihara with the title "Righteous Among the Nations" for his aid to refugees in Lithuania.

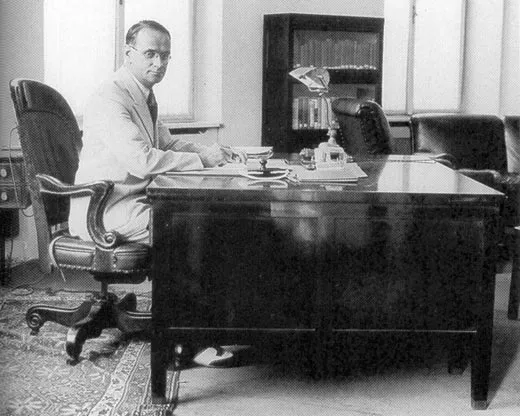

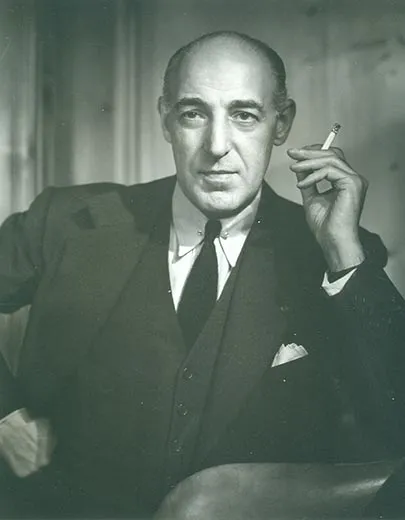

Charles "Carl " Lutz (1895-1975) was appointed the Swiss vice-consul in Budapest, Hungary, in 1942. After the Nazis occupied Hungary in March 1944 and began sending Jews to death camps, Lutz negotiated with the Nazis and the Hungarian government to allow him to issue protective letters to 8,000 Hungarian Jews for emigration to Palestine. Deliberately misinterpreting the agreement to mean 8,000 families, not individuals, he issued tens of thousands of protective letters. A year earlier, he had helped 10,000 Jewish children emigrate to Palestine from Hungary. He also established 76 safe houses in the Budapest area by calling them Swiss annexes. Working with his wife Gertrud, he was able to liberate Jews from deportation centers and death marches. He is credited with saving 62,000 Jews from the Holocaust. After the war, Lutz was admonished for exceeding his authority in helping Jews, but in 1958 he was rehabilitated by the Swiss government. The Yad Vashem honored him and his wife with the title "Righteous Among the Nations" in 1964 and he has been declared an honorary citizen of the state of Israel.

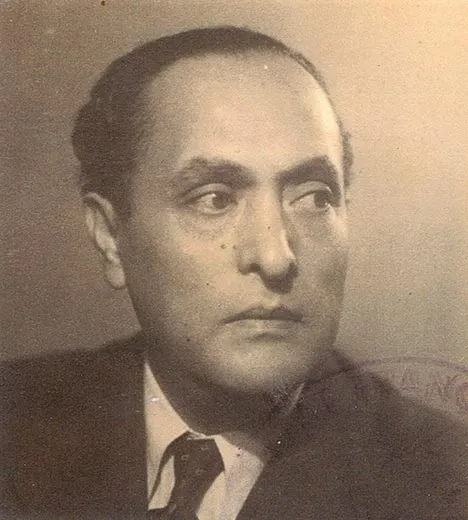

Feng-Shan Ho (1901-1997) became the Chinese consul general in Vienna soon after Nazi Germany annexed Austria in March 1938. After Kristallnacht—a night in November 1938 when synagogues and Jewish businesses in Germany were ransacked and burned and scores of Jews killed or deported to concentration camps— requests for visas skyrocketed. In order to be released from detention, Jews needed emigration documents. Despite orders from his superior to desist, Ho issued those lifesaving visas, sometimes as many as 900 in one month. One survivor, Hans Kraus, who had waited hours outside the Chinese embassy, thrust his requests into the window of Ho's car; a few days later he received his visa. Eric Goldstaub recalls being granted 20 visas, enough for his entire family to flee Austria. Ho was reassigned in 1940 and went on to serve 40 years as a diplomat. He retired to San Francisco in 1973. It was only upon his death that evidence of his humanitarian assistance to Jews came to light. He was posthumously awarded the title of Righteous Among the Nations in 2001 and is known as "China's Schindler."

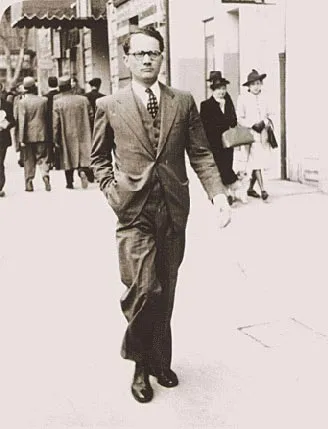

Varian Fry (1907-1967) was an American journalist when he volunteered in 1940 to head up the Emergency Rescue Committee, a private American relief organization supported by first lady Eleanor Roosevelt. The purpose of the agency was to aid refugees in Nazi-occupied France and ship them out before they could be arrested and sent to concentration camps. Operating from a list that included distinguished artists, writers, scholars, politicians, and labor leaders, Fry set out to provide financial support for the refugees and to secure the necessary papers for their escape. He enlisted the aid of sympathetic diplomats such as Harry Bingham IV and Myles Standish, the U.S. vice consuls in Marseilles. Fry established a French relief organization to use as a cover his operation. For 13 months, from August 1940 to 1941, he and his band of volunteers used bribery, back market funds, forged documents, clandestine mountain routes and any means possible to help rescue more than 2,000 people from France. In 1994, Israel awarded him Righteous Among the Nations status.

Raoul Wallenberg (1912-?), trained as an architect, was appointed first secretary at the Swedish legation in Budapest in July 1944 with the mission to save as many Budapest Jews as possible. The Germans were deporting thousands of Jews each day to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. Recruited specifically to organize a mission that would rescue Jews from deportations, Wallenberg circumvented many of the usual diplomatic channels. Bribes, extortion and fake documents were commonplace and produced quick results. He redesigned Swedish protective papers, which identified Hungarian Jews as Swedish subjects. The yellow and blue passes with the Swedish coat of arms usually passed muster with the German and Hungarian authorities, who were sometimes bribed as well. Wallenberg established some 30 "Swedish" houses where Jews could take refuge. Increasingly bold, he intercepted a train bound for Auschwitz, distributed his protective passes, and removed Jews from the cattle cars. On numerous occasions, he saved Jews from death marches. When the Soviet army arrived in Budapest in January 1945, he was arrested and eventually disappeared into the Soviet prison system. Though there were rumors of sightings of him and of his execution, there is still nothing conclusive about what happened to him. In just six months, Wallenberg had saved tens of thousands of Jewish lives. He is honored throughout the world as well as a recipient of Israel's Righteous Among the Nations award.