Flappers Took the Country by Storm, But Did They Ever Truly Go Away

Women of the Roaring Twenties had a lot in common with today’s millennials

:focal(1035x843:1036x844)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a7/56/a756cadb-418b-4611-af17-7e6dd65ab828/sep2017_i04_prologue.jpg)

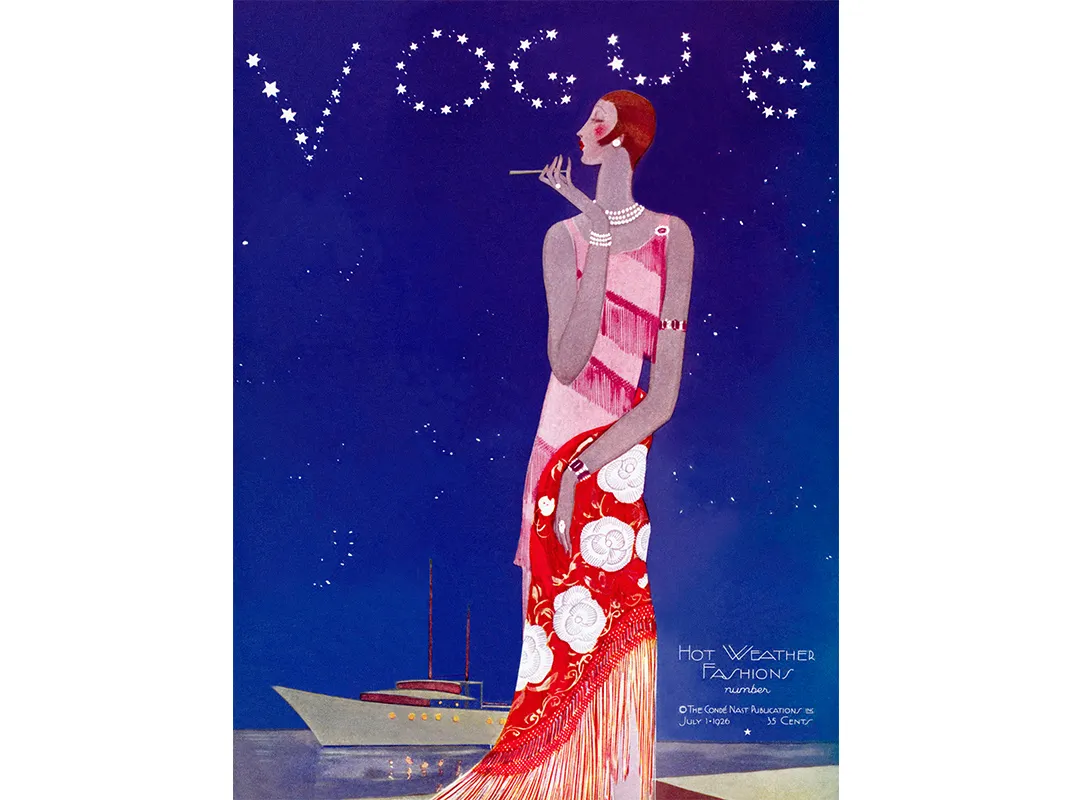

She was the sexy ingénue, spending evenings in jazz clubs hazy with her cigarette smoke. She cavorted, wild and willful, in the stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald, who summed her up as “pretty, impudent, superbly assured, as worldly-wise, briefly-clad and ‘hard-berled’ as possible.”

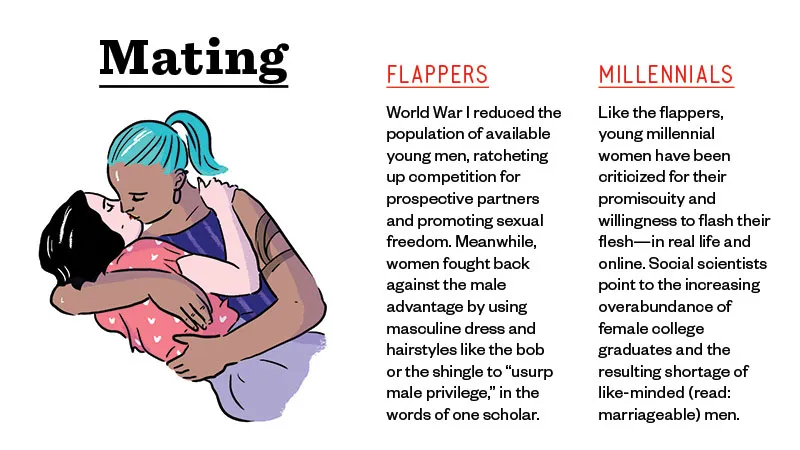

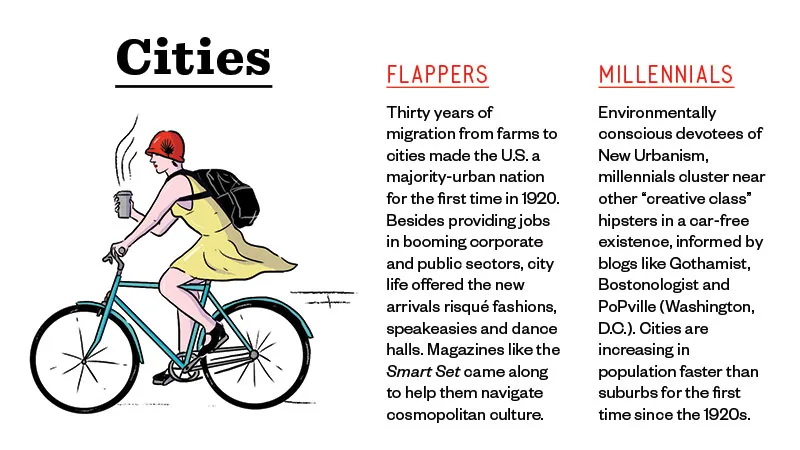

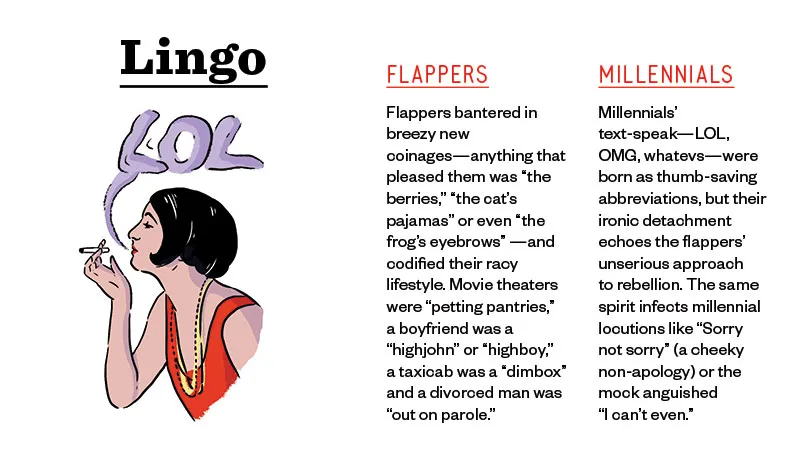

The glamorous, shimmering flapper in her slinky dress and stylish bob seemed to emerge into American life out of nowhere after the First World War, but the term was already familiar by then. In 1890s Britain, in fact, “flapper” described a very young prostitute, and after the turn of the century, it was used on both sides of the Atlantic for cheeky, prepubescent girls whose long braids, the New York Times reported, “flapped in the wind.” Soon, a flapper was any girl or woman who defied convention—girls who balked at being chaperoned, suffragists, women aspiring to a career, and those, as the Boston Globe put it, “expert in the arts of allurement.”

Lost Girls: The Invention of the Flapper

Lost Girls is an illuminating history of the iconic flapper as she evolved from a problem to a temptation, and finally, in the 1920s and beyond, to an aspiration.

Unlike their mothers and grandmothers, flappers tended to go to high school and even college, and they devoured new books featuring confident, fun-loving adolescent heroines who hiked and camped and solved mysteries. Flappers biked, played golf and tennis, and strove to emulate the flat-chested and hipless physiques of the adolescent boys whose freedom and lack of domestic responsibilities they envied.

Predictably, these stylish tomboys were a grave source of worry to parents, educators, physicians and clergymen, who feared that sports and higher education would be ruinous. “Without womanly ideals the female character is threatened with disintegration,” warned G. Stanley Hall, a leading psychologist and educator who toured the country lecturing on the subject.

Other critics focused on the freewheeling, frivolous and “fast” behavior of those same girls who now stayed out all night dancing, sipping booze from hip flasks (it was Prohibition, after all) and petting in roadsters. “She is simply a fool,” the Globe said. “She has no ideas, no definite aims beyond the ever-paramount desire to insure for herself what she is pleased to call ‘as good a time as possible.’”

All the scolding and finger-wagging, of course, only enhanced her appeal. Movies such as The Perfect Flapper, Dancing Mothers and Flaming Youth made young stars of Clara Bow, Olive Thomas and Colleen Moore. (Bow so completely embodied the flapper’s allure that her performance as a plucky shopgirl in the 1927 romantic comedy It led critics, coining a phrase, to call her the “It girl.”) New cosmetics companies sold skin creams to eradicate wrinkles. Magazines advertised flapper hairstyles and clothing—plus extreme diets and dubious claims for the slimming effects of cigarettes and chewing gum. Some women resorted to a new vogue in cosmetic surgery, kicking off an era of damaging self-scrutiny and obsession with weight, youthfulness and body image familiar to us today.

But the flapper, despite her notorious frivolity, was also a version of the “new woman,” who fought for independence, equality in marriage and pay and a political voice. Though the prominent suffragist Rheta Childe Dorr pooh-poohed the “bobbed-haired young female” who “does not read much,” a number of impressively talented women were flappers, including the novelist and screenwriter Anita Loos, the satirist Dorothy Parker and the entertainer Josephine Baker, who went on to become a leading civil rights activist.

Flappers receded from American life after the Great Depression pulled the plug on all the revelry. With the rise of feminism in the 1960s they enjoyed a bit of a revival, but were remembered largely for their racy fashions, short skirts being a symbol of sexual liberation. Feminists had an understandable, get-down-to-business side that was fiercely at odds with the flappers’ devotion to a whimsical, prolonged adolescence; a flapper cheerfully called herself a “girl,” whereas feminists disdained the word as an insult.

Today, though, things have turned again. Many young feminists embrace the flapper’s sassy, independent spirit of seeming to play at adulthood, and are perfectly comfortable referring to themselves as “girls”—notably, the questing young women on Lena Dunham’s TV show “Girls.” Flapper styles may be relegated to costume museums, but the flapper spirit lives again after a hundred years.

What Did Flappers Want? You May Want to Ask a Millennial

Not that today’s hipsters flaunt cigarettes and dance the Charleston. But from their nifty gadgets to their prolonged adolescence, young cosmopolitan women are surprisingly close in sensibility to “girls” of a century ago. -- Paul O'Donnell

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.