For General Patton’s Family, Recovered Ground

Famed World War II Gen. George S. Patton’s grandson finds his calling in the ashes of his fathers journals

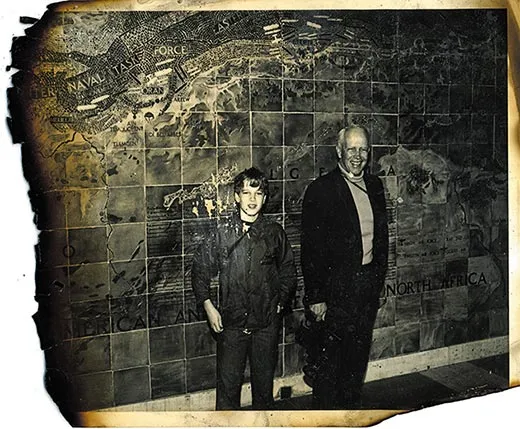

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Benjamin-W-Patton-and-General-George-S-Patton-1978-North-American-Cemetery-Tunisia-631.jpg)

In 1986, the year I turned 21, my father accidentally set fire to our basement. Until then he could often be found down there, in the office he'd carved out for himself in a far corner, smoking a cigar and working on his diaries. He'd been keeping them—dozens of identical volumes bound in red canvas—for most of his adult life.

In the span of a few hours, the flames that rose from the smoldering butt he'd tossed in the wastebasket destroyed two rooms. My father suffered second-degree burns trying to rescue his journals, but nearly all of them were reduced to ash.

A year later, a conservator handed us what was left of them, suggesting to Dad that he could review these scraps for an autobiography and start anew. Instead, my father—the namesake and only son of the World War II general George S. Patton Jr., and a decorated general and famously tough warrior in his own right—choked up. "I'm sorry, I just can't," he said. And he never did.

Someone once told me that when a person dies, it's like a library burning down. My dad reversed the idea: the burning of his office extinguished something in him.

History had always formed a huge part of our family life; the fact that my grandfather had kept thousands of pages of his own letters and diaries—later published as The Patton Papers—was no fluke. As kids, my four siblings and I were fed a steady diet of biographies. Wherever we lived—Kentucky, Alabama, Texas, Germany—we spent a lot of time trudging through battlefields and other historical sites. After the basement fire, assorted family relics dating back to the Civil War era were restored, cataloged and donated to museums. The oil portrait of my grandfather that was represented in the film Patton now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Other keepsakes went to West Point and the Patton Museum in Kentucky, and each has a story. For just one example, there's a gold coin that my great-great-grandfather, Confederate Col. George Patton, carried in his vest pocket during the Civil War. When a Yankee Minié ball struck him during the Battle of Giles Court House in 1862, the coin deflected the bullet just enough to prevent it from penetrating his gut and likely killing him.

A year or so after the fire, I offered to interview my father on audiotape. I wanted to do it partly for our family and partly for him. The loss of his journals had caused him even more sorrow than his retirement from the military six years earlier. I wanted him to be able to share his stories with someone who cared—and who found them inherently valuable.

I was the right age to listen. My father had left for the second of his three tours in Vietnam about the time I was a year old, and my first memory of him is when we flew to Hawaii on R & R to meet him when I was about 3. My mother still teases me about my tugging on her dress at the airport and asking, "What did you say his name was? Daddy?"

As a child, my father had been quite close to his own father: they rode horses, read poetry and even built a 22-foot motorboat together in the garage. But after my dad left for boarding school at 13, they communicated mainly through letters, most of which were a formal, man-to-man mix of advice and strategy. A 1944 letter written from Europe to my dad, who had just flunked math, captures the tenor of their new relationship: "Get as high a stand in math as you can before you hit the stuff you flunked on. In that way, you have further to retreat. It's just like war: in a delaying action, meet the enemy as far out as possible."

During college, my father saw his father only twice—once before then-Maj. Gen. Patton left for North Africa as part of the secret Operation Torch invasion force in 1942 and again briefly just after the war, when my grandfather returned to the States for a War Bond tour featuring victory parades in Boston and Los Angeles. Then he returned to Germany, where he died December 21, 1945, at age 60, after breaking his neck in an automobile accident.

My father turned 22 just days later, and the pressure to live up to his father's legend was already building. When he graduated from West Point the following June, an old veteran shook his hand and said, "Well, George, you'll never be the man your father was, but congratulations."

One thing my father resolved to be was a family man. Even though he became a general himself and was often immersed in his military duties, he went out of his way to spend time with us. And while he never claimed to be an expert in anything nonmilitary, he was a first-class enthusiast. If he went hunting or fishing with friends or fellow soldiers, he often took me or one of my siblings along. He played the guitar at family parties (a self-proclaimed "three-chord man") and taught us how to ski, sail and play tennis. Sailing, he'd invite my friends and me to stay up half the night playing poker in an invariably smoke-filled cabin. He encouraged my brother George, developmentally delayed from birth, to compete in the Special Olympics and also become a champion barrel racer. During rare visits from my sister Margaret, who had become a Benedictine nun over Dad's initial protests, he'd get up early to pick blueberries for her breakfast. He wrote my mother silly but heartfelt poems.

People often said he had the voice my grandfather wished he had—my grandfather's voice was high-pitched with a slightly patrician lilt, while my father actually sounded like George C. Scott. But even when I clashed with him as a teenager, I saw through his tough, hard-edged persona.

At 21, I was just starting to appreciate the fact that my father was—and always had been—one of my biggest supporters and closest friends. Everyone had a story about him. With our audiotaping project, I would get to hear them firsthand.

Over the next six years we spent many hours talking, with me picking his brain for every detail and vignette he could remember. Once we got going, it was as though a massive vault had been opened, and the stories began to pour out. He spoke of being bounced on Gen. John J. "Black Jack" Pershing's knee as a young boy, walking Gen. George C. Marshall's dog and being pulled out of school by his father to attend a talk by British soldier T. E. Lawrence (also known as Lawrence of Arabia). At 13, my father sailed from Hawaii to Southern California aboard a small schooner with his parents, a few of their friends and a professional mate. "We went through a school of blackfin tuna for four days straight," he told me. "They stirred up so much phosphorus [in fact, bioluminescent plankton] in the water that you could actually read a book on deck at night."

He also told me about a fellow West Point graduate who had served under him when my father commanded the storied 11th Armored Cavalry ("Blackhorse") Regiment in Vietnam in 1968-69. His unit had performed poorly under fire, and the young captain asked to be relieved. After a long talk with my father—a colonel at the time—he changed his mind and asked for one more chance to get his outfit into shape before relinquishing command. In a subsequent firefight, the captain earned the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation's second-highest award for valor in combat. "Although terribly costly to him, he chose the harder right rather than the easier wrong," said my dad. "And that's what wins battles. That's what wins wars."

I didn't need to ask about the captain's fate. The John Hays plot at our family's farm in Massachusetts is just one of many that my dad named for soldiers killed under his command. To us, the hand-painted signs all over our property mark just how deeply Dad felt the loss of his troops. Even today, veterans come and quietly wander our fields.

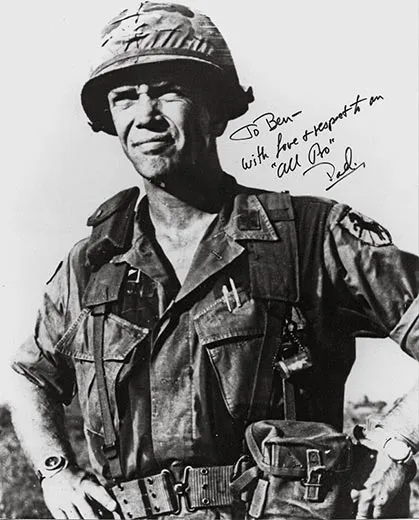

What our taped conversations helped me realize was that my dad was every bit the soldier that his father was. He saw more actual frontline combat and was just as highly decorated by his country for valor. He commanded more than 4,400 men—the largest combat unit led by someone of his rank and age during Vietnam—and more than once landed in his helicopter in the middle of a battle, pulled out his revolver and led the charge. Along the way, he earned the nation's second- and third-highest medals for bravery—twice each—and a Purple Heart. When he retired to Massachusetts in 1980, Dad started a produce farm on the family property. Today, Green Meadows Farm, north of Boston, is a thriving organic operation with the participation of more than 300 local families.

My father didn't boast about his achievements, and he didn't want to be seen as iconic. Maybe that's why he never worked in my grandfather's home office, with its voluminous library and perfect replica of Napoleon's desk. "Too much damn traffic," Dad would say. Then he'd head off to his plywood-walled office in the basement, every surface a collage of photos of fellow soldiers and family.

Re-examining his life had always kept him engaged; now, our interviews revived him. Eventually, Dad gave the transcripts to a biographer, and a book about his life—Brian Sobel's The Fighting Pattons—was published after all.

I disappointed my father when I chose not to follow him into the military, and I frustrated him even more when I dawdled about a career. But here's the strange thing: after our taping was finished, other families with stories to preserve began to find me.

Over the past several years, I've found myself, camera in hand, sitting with the family of an African-American general on the eve of his 80th birthday; a well-born Bostonian who drove an ambulance in World War II and then moved out West to ride in rodeos and raise cattle; an aeronautical engineer and senior executive in the Apollo program who was among the first to propose a moon landing to President John F. Kennedy; even Manfred Rommel, former longtime mayor of Stuttgart and son of the famed "Desert Fox" of World War II. I found a career as a producer and film educator, much of which I devote to recording personal histories.

After a long struggle with Parkinson's disease, my father passed away in the summer of 2004. He was 80 years old and had lived as full a life as anyone could. I'd like to think that, were he still here, he would respect what I'm doing and understand why I'm doing it. In fact, many of my film projects involve working with veterans. Things have kind of circled back.

Every family has a story, and every member's story is worth preserving—certainly for the living family, but even more so for future generations. Experiencing history through the lens of another person's life can offer unexpected insight into your own. It gets you to think: What sort of mark will I make? How will I be remembered?

The key is to start now, whether with a tape recorder or video camera. In her wonderful book The Writing Life, Annie Dillard tells of a note found in Michelangelo's studio after he died. I have a copy pinned up in my office. Scribbled by the elderly artist to an apprentice, it reads: "Draw, Antonio, draw, Antonio, draw and do not waste time."

Benjamin W. Patton, a filmmaker based in New York City, can be reached at [email protected].