The Forgotten Story of the American Troops Who Got Caught Up in the Russian Civil War

Even after the armistice was signed ending World War I, the doughboys clashed with Russian forces 100 years ago

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bd/43/bd43202e-cffe-48b1-b83b-18d2b5d57adb/gettyimages-464428811_web.jpg)

It was 45 degrees below zero, and Lieutenant Harry Mead’s platoon was much too far from home. Just outside the Russian village of Ust Padenga, 500 miles north of Moscow, the American soldiers crouched inside two blockhouses and trenches cut into permafrost. It was before dawn on January 19, 1919.

Through their field glasses, lookouts gazed south into the darkness. Beyond the platoon’s position, flares and rockets flashed, and shadowy figures moved through tiny villages—Bolshevik soldiers from Russia’s Red Army, hoping to push the American invaders 200 miles north, all the way back to the frozen White Sea.

The first artillery shell flew at the Americans at dawn. Mead, 29, of Detroit, awoke, dressed, and ran to his 47-man platoon’s forward position. Shells fell for an hour, then stopped. Soldiers from the Bolshevik Red Army, clad in winter-white uniforms, rose up from the snow and ravines on three sides. They advanced, firing automatic rifles and muskets at the outnumbered Americans.

“I at once realized that our position was hopeless,” Mead recalled, as quoted in James Carl Nelson’s forthcoming book, The Polar Bear Expedition: The Heroes of America’s Forgotten Invasion of Russia. “We were sweeping the enemy line with machine gun and rifle fire. As soon as one wave of the enemy was halted on one flank another was pressing in on us from the other side.”

The Polar Bear Expedition: The Heroes of America's Forgotten Invasion of Russia, 1918-1919

Award-winning historian James Carl Nelson's The Polar Bear Expedition draws on an untapped trove of firsthand accounts to deliver a vivid, soldier's-eye view of an extraordinary lost chapter of American history.

As the Red Army neared, with bayonets fixed on their guns, Mead and his soldiers retreated. They ran through the village, from house to house, “each new dash leaving more of our comrades lying in the cold and snow, never to be seen again,” Mead said. At last, Mead made it to the next village, filled with American soldiers. Of Mead’s 47-man platoon, 25 died that day, and another 15 were injured.

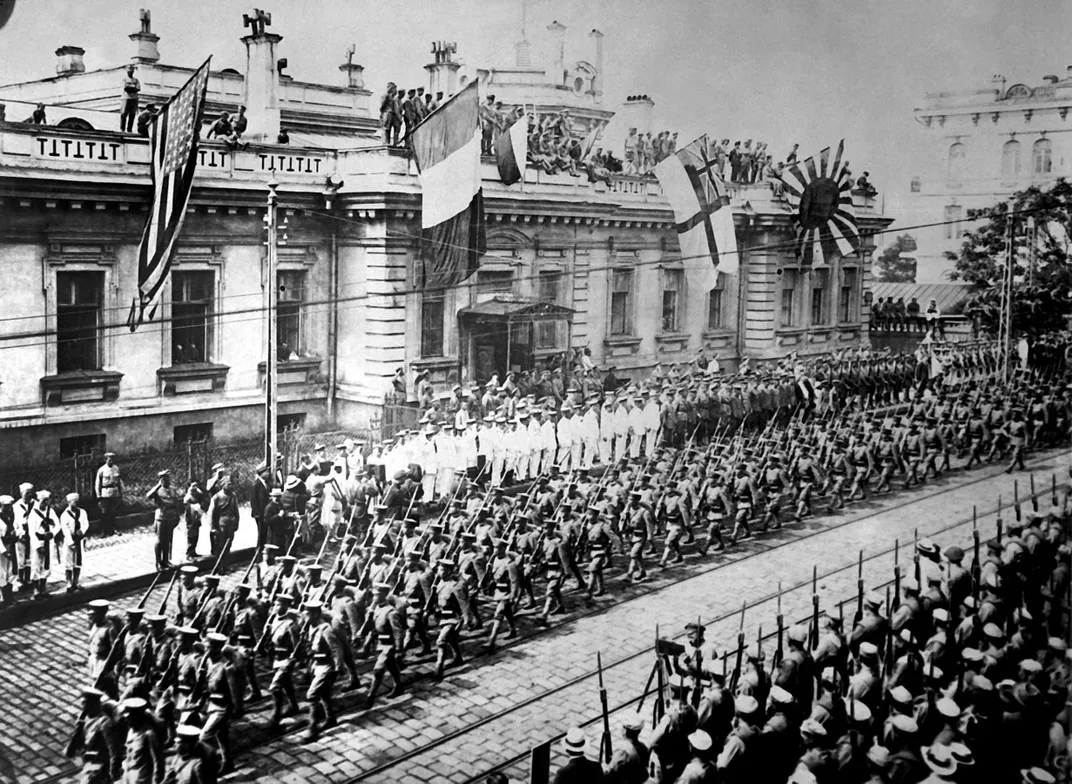

For the 13,000 American troops serving in remote parts of Russia 100 years ago, the attack on Mead’s men was the worst day in one of the United States’ least-remembered military conflicts. When 1919 dawned, the U.S. forces had been in Russia for months. World War I was not yet over for the 5,000 members of the 339th U.S. Army regiment of the American Expeditionary Force deployed near the port city of Archangel, just below the Arctic Circle, nor for the 8,000 troops from the 27th and 31st regiments, who were stationed in the Pacific Ocean port of Vladivostok, 4,000 miles to the east.

They had become bit players caught up in the complex international intrigue of the Russian Civil War. Russia had begun World War I as an ally of England and France. But the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, led by Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky, installed a communist government in Moscow and St. Petersburg that pulled Russia out of the conflict and into peace with Germany. By fall 1918, Lenin’s year-old government controlled only a part of central European Russia. Forces calling themselves the White Russians, a loose coalition of liberals, social democrats and loyalists to the assassinated czar, were fighting the Communists from the north, south, east and west.

Two months after the November 11, 1918, armistice that officially ended the war for the rest of Europe, as one million Americans in France were preparing to sail home, the U.S. troops in Russia found that their ill-defined missions had transformed into something even more obscure. Historians still debate why President Woodrow Wilson really sent troops to Russia, but they tend to agree that the two missions, burdened by Wilson’s ambiguous goals, ended in failures that foreshadowed U.S. foreign interventions in the century to come.

When Wilson sent the troops to Russia in July 1918, World War I still looked dire for the Allies. With the Russian Empire no longer engaged in the continental struggle, Germany had moved dozens of divisions to France to try to strike a final blow and end the war, and the spring 1918 German offensive had advanced to within artillery range of Paris.

Desperate to reopen an Eastern Front, Britain and France pressured Wilson to send troops to join Allied expeditions in northern Russia and far eastern Russia, and in July 1918, Wilson agreed to send 13,000 troops. The Allied Powers hoped that the White Russians might rejoin the war if they defeated the Reds.

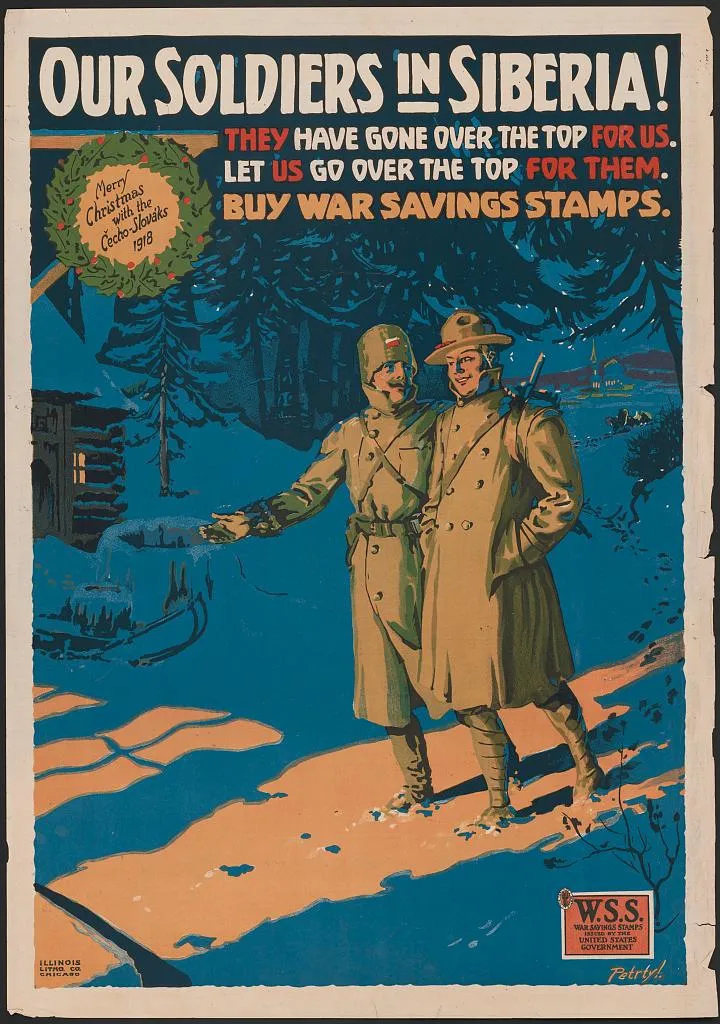

To justify the small intervention, Wilson issued a carefully worded, diplomatically vague memo. First, the U.S. troops would guard giant Allied arms caches sent to Archangel and Vladivostok before Russia had left the war. Second, they would support the 70,000-man Czechoslovak Legion, former prisoners of war who had joined the Allied cause and were fighting the Bolsheviks in Siberia. Third, though the memo said the U.S. would avoid “intervention in [Russia’s] internal affairs,” it also said the U.S. troops would aid Russians with their own “self-government or self-defense.” That was diplomacy-speak for aiding the White Russians in the civil war.

“This was a movement basically against the Bolshevik forces,” says Doran Cart, senior curator at the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City. “[But] we couldn’t really go in and say, ‘This is for fighting the Bolsheviks.’ That would seem like we were against our previous ally in the war.”

Wilson’s stated aims were so ambiguous that the two U.S. expeditions to Russia ended up carrying out very different missions. While the troops in north Russia became embroiled in the Russian Civil War, the soldiers in Siberia engaged in an ever-shifting series of standoffs and skirmishes, including many with their supposed allies.

The U.S. soldiers in northern Russia, the U.S. Army’s 339th regiment, were chosen for the deployment because they were mostly from Michigan, so military commanders figured they could handle the war zone’s extreme cold. Their training in England included a lesson from Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton on surviving below-zero conditions. Landing in Archangel, just below the Arctic Circle, in September 1918, they nicknamed themselves the Polar Bear Expedition.

Under British command, many of the Polar Bears didn’t stay in Archangel to guard the Allied arms cache at all. The British goal was to reach the Russian city of Kotlas, a railroad crossing where, they hoped, they might use the railway to connect with the Czechoslovak Legion in the east. So British officer Lieutenant General Frederick Poole deployed the Polar Bears in long arcs up to 200 miles south of Archangel, along a strategic railroad and the Dvina and Vaga rivers.

But they never got to Kotlas. Instead, the Allied troops’ overextended deployment led to frequent face-to-face combat with the Bolshevik army, led by Leon Trotsky and growing in strength. One company of Americans, along with Canadian and Scottish troops, fought a bloody battle with Bolshevik forces on November 11, 1918 -- Armistice Day in France.

“Events moved so fast in 1918, they made the mission moot,” says Nelson, author of The Polar Bear Expedition. “They kept these guys in isolated, naked positions well into 1919. The biggest complaint you heard from the soldiers was, ‘No one can tell us why we’re here,’ especially after the Armistice.” The Bolshevik Revolution had “dismayed” most Americans, Russia scholar Warren B. Walsh wrote in 1947, “mostly because we thought that the Bolsheviks were German agents or, at least, were playing our enemy’s game.” But with Germany’s defeat, many Americans -- including many Polar Bears -- questioned why U.S. troops were still at war.

While the Polar Bears played a reluctant role in the Russian Civil War, the U.S. commander in Siberia, General William Graves, did his best to keep his troops out of it. In August 1918, before Graves left the U.S., Secretary of War Newton Baker met the general to personally hand him Wilson’s memo about the mission. “Watch your step; you will be walking on eggs loaded with dynamite,” Baker warned Graves. He was right.

Graves and the AEF Siberia landed in Vladivostok that month with, as Graves later wrote, “no information as to the military, political, social, economic, or financial situation in Russia.” The Czechs, not the Bolsheviks, controlled most of Siberia, including the Trans-Siberian Railway. Graves deployed his troops to guard parts of the railway and the coal mines that powered it -- the lifeline for the Czechs and White Russians fighting the Red Army.

But Russia’s quickly shifting politics complicated Graves’ mission. In November 1918, an authoritarian White Russian admiral, Alexander Kolchak, overthrew a provisional government in Siberia that the Czechs had supported. With that, and the war in Europe over, the Czechs stopped fighting the Red Army, wanting instead to return to their newly independent homeland. Now Graves was left to maintain a delicate balance: keep the Trans-Siberian Railway open to ferry secret military aid to Kolchak, without outright joining the Russian Civil War.

Opposition to the Russia deployments grew at home. “What is the policy of our nation toward Russia?” asked Senator Hiram Johnson, a progressive Republican from California, in a speech on December 12, 1918. “I do not know our policy, and I know no other man who knows our policy.” Johnson, a reluctant supporter of America’s entry into World War I, joined with anti-war progressive Senator Robert La Follette to build opposition to the Russia missions.

The Bolsheviks’ January 1919 offensive against American troops in north Russia -- which began with the deadly attack on Mead’s platoon -- attracted attention in newspapers across the nation. For seven days, the Polar Bears, outnumbered eight to one, retreated north under fire from several villages along the Vaga River. On February 9, a Chicago Tribune political cartoon depicted a giant Russian bear, blood dripping from its mouth, confronting a much smaller soldier holding the U.S. flag. “At Its Mercy,” the caption read.

On February 14, Johnson’s resolution challenging the U.S. deployment in north Russia failed by one vote in the Senate, with Vice President Thomas Marshall breaking a tie to defeat it. Days later, Secretary of War Baker announced that the Polar Bears would sail home “at the earliest possible moment that weather in the spring will permit” -- once the frozen White Sea thawed and Archangel’s port reopened. Though Bolshevik attacks continued through May, the last Polar Bears left Archangel on June 15, 1919. Their nine-month campaign had cost them 235 men. “When the last battalion set sail from Archangel, not a soldier knew, no, not even vaguely, why he had fought or why he was going now, and why his comrades were left behind -- so many of them beneath the wooden crosses,” wrote Lieutenant John Cudahy of the 339th regiment in his book Archangel.

But Wilson decided to keep U.S. troops in Siberia, to use the Trans-Siberian Railway to arm the White Russians and because he feared that Japan, a fellow Allied nation that had flooded eastern Siberia with 72,000 troops, wanted to take over the region and the railroad. Graves and his soldiers persevered, but they found that America’s erstwhile allies in Siberia posed the greatest danger.

Sticking to Wilson’s stated (though disingenuous) goal of non-intervention in the Russian Civil War, Graves resisted pressure from other Allies—Britain, France, Japan, and the White Russians—to arrest and fight Bolsheviks in Siberia. Wilson and Baker backed him up, but the Japanese didn’t want the U.S. troops there, and with Graves not taking their side, neither did the White Russians.

Across Siberia, Kolchak’s forces launched a reign of terror, including executions and torture. Especially brutal were Kolchak’s commanders in the far east, Cossack generals Grigori Semenov and Ivan Kalmikov. Their troops, “under the protection of Japanese troops, were roaming the country like wild animals, killing and robbing the people,” Graves wrote in his memoir. “If questions were asked about these brutal murders, the reply was that the people murdered were Bolsheviks and this explanation, apparently, satisfied the world.” Semenov, who took to harassing Americans along the Trans-Siberian Railway, commanded armored trains with names such as The Merciless, The Destroyer, and The Terrible.

Just when the Americans and the White Russian bandits seemed on the verge of open warfare, the Bolsheviks began to win the Russian Civil War. In January 1920, near defeat, Kolchak asked the Czech Legion for protection. Appalled at his crimes, the Czechs instead turned Kolchak over to the Red Army in exchange for safe passage home, and a Bolshevik firing squad executed him in February. In January 1920, the Wilson administration ordered U.S. troops out of Siberia, citing “unstable civil authority and frequent local military interference” with the railway. Graves completed the withdrawal on April 1, 1920, having lost 189 men.

Veterans of the U.S. interventions in Russia wrote angry memoirs after coming home. One Polar Bear, Lieutenant Harry Costello, titled his book, Why Did We Go To Russia? Graves, in his memoir, defended himself against charges he should’ve aggressively fought Bolsheviks in Siberia and reminded readers of White Russian atrocities. In 1929, some former soldiers of the 339th regiment returned to North Russia to recover the remains of 86 comrades. Forty-five of them are now buried in White Chapel Cemetery near Detroit, surrounding a white statue of a fierce polar bear.

Historians tend to see Wilson’s decision to send troops to Russia as one of his worst wartime decisions, and a foreshadowing of other poorly planned American interventions in foreign countries in the century since. “It didn’t really achieve anything—it was ill-conceived,” says Nelson of the Polar Bear Expedition. “The lessons were there that could’ve been applied in Vietnam and could’ve been applied in Iraq.”

Jonathan Casey, director of archives at the World War I Museum, agrees. “We didn’t have clear goals in mind politically or militarily,” he says. “We think we have an interest to protect, but it’s not really our interest to protect, or at least to make a huge effort at it. Maybe there are lessons we should’ve learned.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.