The Forgotten History of Women’s Football

Several women’s football leagues formed during the 20th century—one from the 1930s even became a national sensation—but they’re barely remembered today

This season, to much media acclaim, the National Football League hired its first female referee and two female coaches (one intern and one full-time). Considering the attention these additions generated, one could be forgiven for thinking that women were just beginning to get into the sport at any professional level. But in the period between World War I and II, a women’s football league was nearly popular enough to become mainstream entertainment.

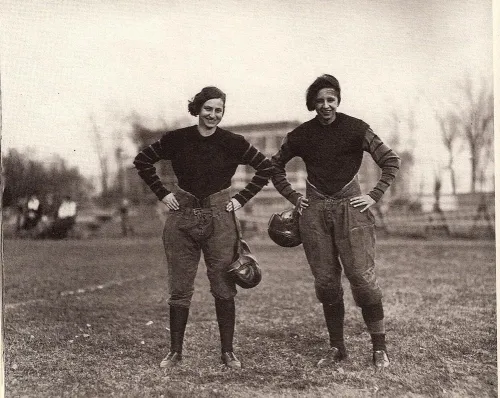

Little is known about this short-lived women’s football craze. What remains are the photographs of players from Los Angeles that appeared in two national magazines: first Life in November 1939, then Click the following January. The black-and-white photos showed tough-looking women dressed in full football uniforms, including helmets, pants and shoulder pads. The magazine articles provided hardly any information about these pioneering athletes, though, other than assuring readers that they played “hard, fast” regulation tackle football.

Who were these women, and why did their football league disappear after only one season, despite the Click article’s assertion that it would be expanding nationwide the next fall? Many might assume that public disapproval was to blame. “There was an identification of football with masculinity, much like boxing or wrestling. For women to be playing it would have been seen as an extreme violation of the gender norms,” says football historian Michael Oriard, who mentions the Los Angeles players in his 2004 book King Football. There may be a different explanation for the league’s demise, though, one that has more to do with the women themselves.

My first clue was one of the teams referred in the Life article: the Marshall-Clampett Amazons. I had come across a Marshall-Clampett fastpitch softball team from Los Angeles while researching my book on the history of the sport (the team was named after its car dealership sponsor). A search of the California newspaper archives turned up an article in the Palm Springs Desert Sun that confirmed the Marshall-Clampett football and softball teams were not only related but were, in fact, the same team—the football players featured in the Life article were actually softball players first and foremost.

It’s likely that the three other teams in the Los Angeles women’s football league were composed of softball players, too. In a 2013 blog post, Melitas Forster, a former Marshall-Clampett player, recalled that a softball promoter had organized the football league. Women’s softball was extremely popular in the late 1930s, especially in Los Angeles, where Hollywood celebrities attended games. The same Desert Sun article discussed a charity softball game between the team and a men’s squad that included silent film star Buster Keaton. (Incidentally, the Marshall-Clampett players wound up defeating Buster Keaton’s Palm Springs team, 5-4.) The women’s football games appear to have been an attempt to capitalize on this popularity and extend ticket sales from fall, when the softball season ended, into winter.

If this was indeed the plan, it worked. In addition to attracting national media attention, the games drew crowds of 3,000 or more.

There were some negative reactions to the women’s football games. A news wire article published November 1939 described them as an invasion of “one of the last strongholds of masculinity.” The Life article also argued that football was too dangerous for women, warning that “a blow either on the breasts or in the abdominal region may result in cancer or internal injury.” Still, the more likely reason the Los Angeles league ended was that the players were already committed to softball, which offered considerably more opportunities than football did. Being featured in national magazines paled in comparison to the perks that came with being a 1930s Los Angeles softball player, which included traveling to overseas destinations, such as Japan, and getting to appear in movies, such as the 1937 Rita Hayworth film Girls Can Play.

Though football was likely more dangerous, the Los Angeles players still played physical enough of a softball game to incur strained muscles and the occasional concussion. But there was little incentive for them to risk hurting themselves playing unless the league expanded, and it didn’t. “Let the boys get their heads kicked off. We’ll stick to softball,” some of the players told the Orange County, California, Daily News.

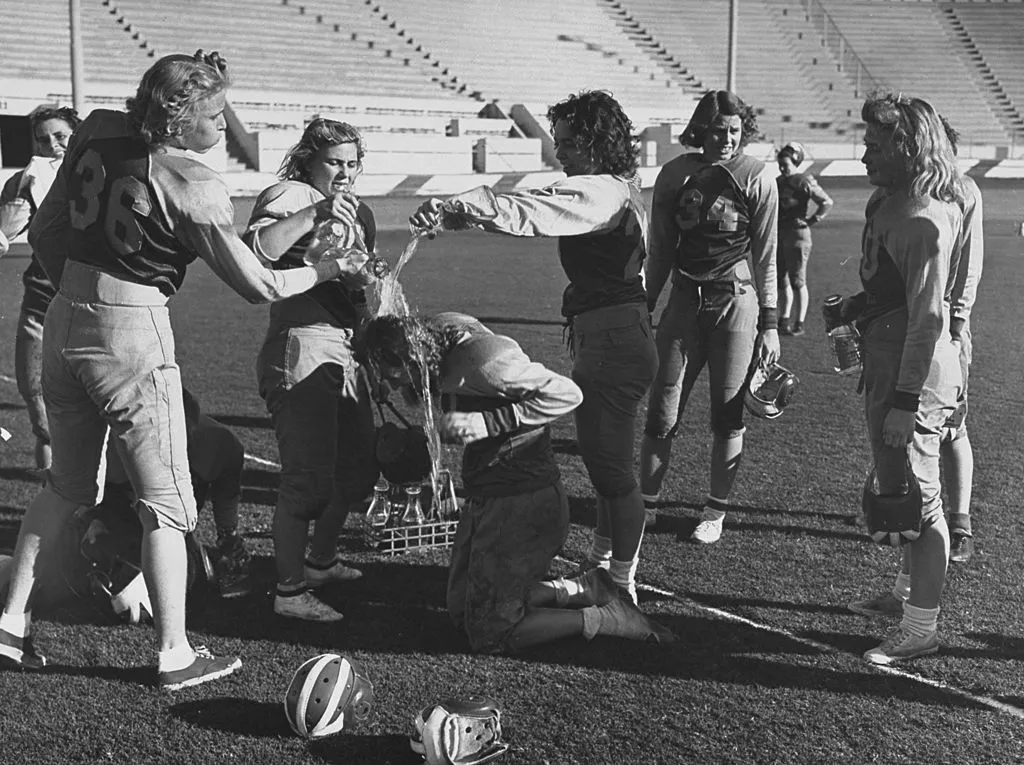

A year later, in the summer of 1941, a second women’s football league attempted to form. This time the setting was Chicago, and once again, many of the players came from softball. The teams only played a few games, though, and they received little publicity other than a few local newspaper articles. By the next year, with the U.S. entrance to World War II, talk of women’s football mostly disappeared until the 1970s, when a semi-professional league based primarily in Ohio and Texas emerged. This league received more media coverage, with articles in magazines, such as Texas Monthly, Ebony and Jet. It failed to reach a wide audience, though, and, like the 1939 California league, was soon forgotten.

The cost-benefit analysis that the Amazons of the 1930s made has had a modern-day resurgence. Retired football player Antwaan Randle-el told The Washington Post that if faced with the decision again to play football or play baseball (he was drafted in the 14th round by the Chicago Cubs), he would select baseball, citing football’s physical toll.

And with the inherent dangers of playing football becoming daily news material, it’s unclear that a professional women’s football league will ever again take hold.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/90/34/90345974-f86f-4ee2-b494-a67a1c543f1e/gettyimages-53370924.jpg)