Fort Monroe’s Lasting Place in History

Famous for accepting escaped slaves during the Civil War, the Virginia base also has a history that heralds back to Jamestown

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Fort-Monroe-Virginia-Civil-War-631.jpg)

As a white child in southern Virginia, I thought his first name was “Beast” because everyone called him that. Gen. Benjamin Franklin Butler was our nemesis—the Union commander of Fort Monroe, at the entrance to southeastern Virginia’s vast natural harbor; the churl who ordered the women of New Orleans to yield the sidewalk whenever Yankee soldiers approached; the officer who returned to oversee the occupation of Norfolk. But I was never told how Butler and Fort Monroe figured in one of the pivotal moments of the Civil War.

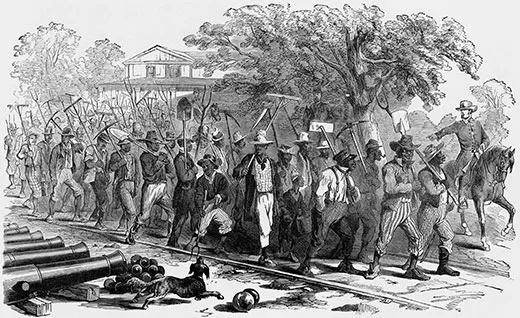

When he arrived on May 22, 1861, Virginians—that is, those white men who qualified—were voting to secede from the Union. That night, three slaves slipped away from the nearby town of Hampton and sought asylum at the immense granite fort on the Chesapeake Bay. They told Butler that they were being sent to build Confederate defenses and did not want to be parted from their families. He allowed them to stay.

Two days later, their owner, a Virginia colonel, demanded their return. Butler’s answer changed American history: the self-taught Massachusetts lawyer said that since Virginia had voted to secede, the Fugitive Slave Act no longer applied, and the slaves were contraband of war. Once word of Fort Monroe’s willingness to harbor escaped slaves spread, thousands flocked to the safety of its guns.

“It has been so overlooked, but this was the first step toward making the Civil War a conflict about freedom,” says John Quarstein, Hampton’s historian. Soon, the escaped slaves were calling the forbidding stone structure “Freedom’s Fortress.” Butler found them work, established camps and provided food, clothing and wages. Some former slaves were taught to read and some joined the U.S. Navy.

At first, President Abraham Lincoln balked at the idea, but on August 6, 1861, Congress approved an act allowing the confiscation of slaves used for military purposes against the United States. The next day, Confederate Col. John Magruder—who had read a New York Tribune report that Butler was planning to turn Hampton into a refuge for former slaves—had his troops burn the town to the ground.

Butler by then had been sent on to other theaters of the war—he suspected Lincoln relieved him of his Fort Monroe command because of his response to the Virginia colonel—but the fort remained a Union stronghold deep in enemy territory throughout the Civil War. Afterward, the fort’s dank casemate served as a prison for Confederate President Jefferson Davis while freed slaves such as Harriet Tubman enjoyed the liberty of the military base. The fort served a strategic purpose until after World War II, when it became a post for writers of Army manuals.

And now the Army is preparing to abandon the fort in September 2011.

That move has been planned since 2005, as part of a Pentagon belt-tightening exercise. The state-chartered Fort Monroe Authority will take over, turning the historic site into a residential community and tourist destination. “We intend to keep it a vibrant and active community,” Bill Armbruster, the authority’s director, told me when I paid a call at Quarters No. 1, just inside the fort’s high walls.

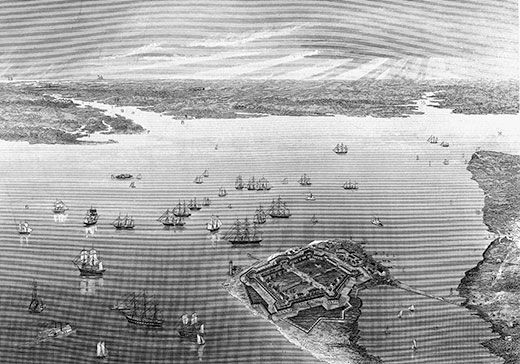

A pounding storm had just passed, and wind whipped across the island as Armbruster, a former civilian Army executive, took me for a tour in the fading light. The fort sits on a spit of land totaling 570 acres, connected to the mainland by a short bridge and bordered on one side by swamp and on the other by the Chesapeake Bay.

Captain John Smith had seen the strategic potential of the site four centuries ago. “A little isle fit for a castle” is how he described the arrowhead-shaped piece of land pointing to the entrance of Hampton Roads, southeastern Virginia’s harbor. By 1609, the colonists had built a plank fort there and equipped it with seven pieces of artillery. It was there, at Fort Algernon, that a Dutch ship offloaded African slaves in exchange for supplies in 1619—the first recorded arrival of Africans in English North America.

Fort George, made of brick, replaced Algernon in the 1730s. “No ship could pass it without running great risks,” Royal Virginia Governor William Gooch wrote in 1736. But 13 years later, a hurricane devastated the structure.

After the British burned Hampton during the War of 1812, using the island and its lighthouse as a temporary base, Congress allocated money for a substantial fort. An aide to Napoleon, Gen. Simon Bernard, designed what is the largest moated fort in North America, a star-shaped masonry structure with 10-foot-thick walls enclosing 63 acres and, by the 1830s, bristling with more than 400 cannon. In time, it became known as the “Gibraltar of the Chesapeake.”

Now, the paint is peeling on the exterior of Quarters No. 1, an elegant 1819 building—the oldest on the post—but the interior retains its grandeur. The Marquis de Lafayette entertained his Virginia friends in the parlor during his triumphant return in 1824. Robert E. Lee, a precocious Army officer, reported for duty at the fort in 1831 to oversee its completion.

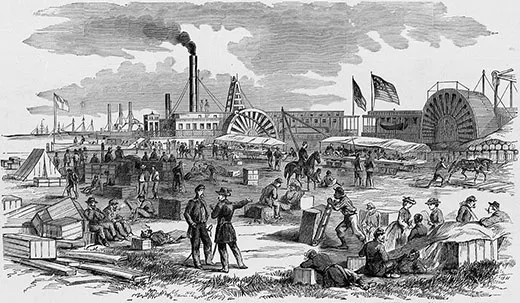

During the Civil War, Fort Monroe served as the key staging ground for Northern campaigns against Norfolk, the Outer Banks of North Carolina and the Southern capital of Richmond. “It was a keystone in the Lincoln administration’s strategy to wage war in Virginia and the Carolinas,” says J. Michael Cobb, curator at the Hampton History Museum. “If Fort Monroe had fallen to Southern forces when Virginia seceded from the Union, the war would have no doubt lasted significantly longer.”

The latest in experimental guns, balloons and other military technologies were tried there. In early 1865, soldiers watched from the ramparts as Lincoln and senior Confederate officials failed to reach a peace agreement during a shipborne conference. It was from Fort Monroe a few months later that the news was telegraphed to Washington that Richmond was finally in Northern hands.

But the fort was also hailed, both before and after the Civil War, as one of the nation’s most prominent resorts, Quarstein says. Presidents Andrew Jackson and John Tyler summered there. And at the adjacent Hygeia Hotel, Edgar Allan Poe gave his last public recitation in 1849 and Booker T. Washington later worked while he studied at the Hampton Normal and Agricultural School. So the Fort Monroe Authority’s redevelopment plan doesn’t mark a complete departure from the past.

Armbruster sees a future in which birders, Civil War enthusiasts and those drawn to the water will come to visit and even live at the fort. With nearly 250 buildings and some 300 housing units, there is plenty of room. As we finished our tour, he pointed at one long, stately building. “Those were Lee’s quarters,” he said in the casual way only a Virginian could muster. “And they are still occupied.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/andrew2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/andrew2.png)