How to Tell 400 Years of Black History in One Book

From 1619 to 2019, this collection of essays, edited by two of the nation’s preeminent scholars, shows the depth and breadth of African American history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/31/de/31deb99d-0dcc-43eb-b801-171fb1aec4bc/gettyimages-515185532.jpg)

In August of 1619, the English warship White Lion sailed into Hampton Roads, Virginia, where the conjunction of the James, Elizabeth and York rivers meet the Atlantic Ocean. The White Lion’s captain and crew were privateers, and they had taken captives from a Dutch slave ship. They exchanged, for supplies, more than 20 African people with the leadership and settlers at the Jamestown colony. In 2019 this event, while not the first arrival of Africans or the first incidence of slavery in North America, was widely recognized as inaugurating race-based slavery in the British colonies that would become the United States.

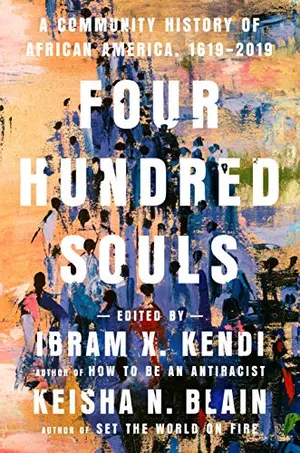

That 400th anniversary is the occasion for a unique collaboration: Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019, edited by historians Ibram X. Kendi and Keisha N. Blain. Kendi and Blain brought together 90 black writers—historians, scholars of other fields, journalists, activists and poets—to cover the full sweep and extraordinary diversity of those 400 years of black history. Although its scope is encyclopedic, the book is anything but a dry, dispassionate march through history. It’s elegantly structured in ten 40-year sections composed of eight essays (each covering one theme in a five-year period) and a poem punctuating the section conclusion; Kendi calls Four Hundred Souls “a chorus.”

The book opens with an essay by Nikole Hannah-Jones, the journalist behind the New York Times’ 1619 Project, on the years 1619-1624, and closes with an entry from Black Lives Matter co-creator Alicia Garza writing about 2014-19, when the movement rose to the forefront of American politics. The depth and breadth of the material astounds, between fresh voices, such as historisn Mary Hicks writing about the Middle Passage for 1694-1699, and internationally renowned scholars, such as Annette Gordon-Reed writing about Sally Hemings for 1789-94. Prominent journalists include, in addition to Hannah-Jones, The Atlantic’s Adam Serwer on Frederick Douglass (1859-64) and New York Times columnist Jamelle Bouie on the Civil War (1864-69). The powerful poems resonate sharply with the essays, Chet’la Sebree’s verses in “And the Record Repeats” about the experiences of young black women, for example, and Salamishah M. Tillet’s account of Anita Hill’s testimony in the Senate confirmation hearings for Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas.

“We are,” Kendi writes in the introduction collectively of black Americans, “reconstructing ourselves in this book.” The book itself, Blain writes in the conclusion, is “a testament to how much we have overcome, and how we have managed to do it together, despite our differences and diverse perspectives.” In an interview, Blain talked about how the project and the book’s distinctive structure developed, and how the editors imagine it will fit into the canon of black history and thought. A condensed and edited version of her conversation with Smithsonian is below.

Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019

Four Hundred Souls is a unique one-volume “community” history of African Americans. The editors, Ibram X. Kendi and Keisha N. Blain, have assembled 90 brilliant writers, each of whom takes on a five-year period of that four-hundred-year span.

How did the Four Hundred Souls book come about?

We started working on the project in 2018 (it actually predates the [publication of] the New York Times 1619 Project.) Ibram reached out to me with the idea that with the 400th year anniversary of the first captive Africans arriving in Jamestown, maybe we should collaborate on a project that would commemorate this particular moment in history, and look at 400 years of African American history by pulling together a diverse set of voices.

The idea was that we'd be able to create something very different than any other book on black history. And as historians, we were thinking, what would historians of the future want? Who are the voices they would want to hear from? We wanted to create something that would actually function as a primary source in another, who knows, 40 years or so—that captures the voices of black writers and thinkers from a wide array of fields, reflecting on both the past but also the present too.

Did you have any models for how you pulled all these voices together?

There are a couple of models in the sense of the most significant, pioneering books in African American history. We thought immediately of W.E.B. De Bois' Black Reconstruction in America in terms of the scope of the work, the depth of the content, and the richness of the ideas. Robin D.G. Kelley's Freedom Dreams is another model, but more recent. Martha Jones' Vanguard, is a book that captures decades right of black women's political activism and the struggle for the vote in a way that I think, does a similar kind of broad, sweeping history. Daina Ramey Berry and Kali N. Gross's Black Woman's History of the United States is another.

But ours was not a single authored book or even an edited collection of just historians. We didn't want to produce a textbook, or an encyclopedia. We wanted this work to be, as an edited volume, rich enough and big enough to cover 400 years of history in a way that would keep the reader engaged from start to finish, 1619 to 2019. That’s part of the importance of the multiple different genres and different voices we included moving from period to period.

How does Four Hundred Souls reflect the concept of a community history?

We figured that community would show up in different ways in the narrative, but we were really thinking initially, how do we recreate community in putting this book together? One of the earliest analogies that Ibram used was describing this as a choir. I love this—he described the poets as soloists. And then in this choir, you'd have sopranos, you'd have tenors, and you’d have altos. And so the question was: Who do we invite to be in this volume that would capture collectively that spirit of community?

We recognized that we could never fully represent every single field and every single background, but we tried as much as possible. And so even in putting together the book, there was a moment where we said, for example, "Wait a minute, we don't really have a scholar here who would be able to truly grapple with the sort of interconnection between African American History and Native American history." So we thought, is there a scholar, who identifies as African American and Native American and then we reached out to [UCLA historian] Kyle Mays.

So there were moments where we just had to be intentional about making sure that we were having voices that represented as much as possible the diversity of black America. We invited Esther Armah to write about the black immigrant experience because what is black America without immigrants? The heart of black America is that it's not homogenous at all—it's diverse. And we tried to capture that.

We also wanted to make sure that a significant number of the writers were women, largely because we acknowledge that so many of the histories that we teach, that we read, and that so many people cite are written by men. There's still a general tendency to look for male expertise, to acknowledge men as experts, especially in the field of history. Women are often sidelined in these conversations. So we were intentional about that, too, and including someone like Alicia Garza, one of the founders of Black Lives Matter, we wanted to acknowledge the crucial role that black women are playing in shaping American politics to this very day.

How did historians approach their subjects differently than say, creative writers?

One of the challenges with the book, which turned out to be also an opportunity, was that we were focusing on key historical moments, figures, themes and places in the United States, each within in a very specific five-year period. We actually spent a lot of time mapping out instructions for authors. It wasn't just: “Write a piece for us on this topic.” We said, “Here's what we want and what we don't want. Here's what we expect of you ask these questions as you're writing the essay, make sure you're grappling with these particular themes.”

But they also had to have a bit of freedom, to look backward, and also to look forward. And I think the structure with a bit of freedom worked, it was a pretty nice balance. Some essays the five years just fit like a glove, others a little less so but the writers managed to pull it off.

We also spent a lot of time planning and carefully identifying who would write on certain topics. “Cotton,” which memoirist Kiese Laymon wrote about for 1804-1809, is a perfect example. We realized very early that if we asked a historian to write about cotton, they would be very frustrated with the five-year constraint. But when we asked Kiese, we let him know that we would provide him with books on cotton and slavery for him to take a look at. And then he brought to it his own personal experience, which turned out to be such a powerful narrative. He writes, “When the land is freed, so will be all the cotton and all the money made off the suffering that white folks made cotton bring to Black folks in Mississippi and the entire South.”

And so that's the other element of this too. Even a lot of people wondered how we would have a work of history with so many non-historians. We gave them clear guidance and materials, and they brought incredible talent to the project.

The New York Times’ 1619 project shares a similar point of origin, the 400th anniversary of the arrival of enslaved Africans to colonial America. What did you make of it when it came out last year?

When the 1619 Project came out, [Ibram and I] were thrilled, because actually, it, in so many ways, complemented our vision for our project. Then we decided we really had to invite Nikole Hannah-Jones to contribute. We weren't sure who we would ask for that first essay, but then we were like, "You know what? This makes sense."

I know there are so many different critiques, but for me, what is most valuable about the project is the way that it demonstrates how much, from the very beginning, the ideas and experiences of black people have been sidelined.

This is why we wanted her to write her essay [about the slave ship White Lion.] Even as someone who studied U.S. history, I did not even know about the White Lion for many years. I mean, that's how sad it is…but I could talk about the Mayflower. That was part of the history that I was taught. And so what does that tell us?

We don't talk about 1619 the way that we do 1620. And why is that? Well, let's get to the heart of the matter. Race matters and racism, too, in the way that we even tell our histories. And so we wanted to send that message. And like I said, to have a complementary spirit and vision as the 1619 Project.

When readers have finished going through 400 Souls, where else can they read black scholars writing on black history?

One of the things that the African American Intellectual History Society [Blain is currently president of the organization] is committed to doing is elevating the scholarship and writing of Black scholars as well as a diverse group of scholars who work in the field of Black history, and specifically Black intellectual history.

Black Perspectives [an AAIHS publication] has a broad readership, certainly, we're reaching academics in the fields of history and many other fields. At the same time, a significant percentage of our readers are non-academics. We have activists who read the blog, well known intellectuals and thinkers, and just everyday lay people who are interested in history, who want to learn more about black history and find the content accessible.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.