Finally, the Beauty of France’s Chauvet Cave Makes its Grand Public Debut

A high-tech recreation of the immortal artworks shines a new light on the dawn of human imagination

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/75/9d/759d0831-61fc-4e60-b7d8-25cf7441cea8/apr2015_h03_chauvetcave.jpg)

As I descend a footpath through subterranean gloom, limestone walls tower 40 feet and plunge into a chasm. Gleaming stalactites dangle from the ceiling. After several twists and turns, I reach a cul-de-sac. As I shine my iPhone flashlight on the walls, out of the darkness emerge drawings in charcoal and red ocher of woolly rhinos, mammoths and other mammals that began to die out during the Pleistocene era, about 10,000 years ago.

It feels, and even smells, like a journey into a deep hole in the earth. But this excursion is actually taking place in a giant concrete shed set in the pine-forested hills of the Ardèche Gorge in southern France. The rock walls are stone-colored mortar molded over metal scaffolding; the stalactites were fashioned from plastic and paint in a Paris atelier. Some of the wall paintings are the work of my guide, Alain Dalis, and the team of fellow artists at his studio, Arc et Os, in Montignac, north of

Toulouse. Dalis pauses before a panel depicting a pride of lions in profile, sketched with charcoal. “These were drawn on polystyrene, a synthetic resin, then fitted to the wall,” he tells me. The result is a precise, transfixing replica of the End Chamber, also called the Gallery of Lions, inside the actual Chauvet Cave, located three miles from here and widely viewed as the world’s greatest repository of Upper Paleolithic art.

The $62.5 million facsimile is called the Caverne du Pont d’Arc, after a nearby landmark—a natural archway of eroded limestone spanning the Ardèche River and known to humans since Paleolithic times. The replica, opening to the public this month, has been in the works since 2007, when the Ardèche departmental government, recognizing that an international audience was clamoring to view the cave, decided to join with other public and private funders to build a simulacrum. Restrictions imposed by the French Ministry of Culture bar all but scientists and other researchers from the fragile environment of the cave itself.

Five hundred people—including artists and engineers, architects and special-effects designers—collaborated on the project, using 3-D computer mapping, high-resolution scans and photographs to recreate the textures and colors of the cave. “This is the biggest project of its kind in the world,” declares Pascal Terrasse, the president of the Caverne du Pont d’Arc project and a deputy to the National Assembly from Ardèche. “We made this ambitious choice... so that everybody can admire these exceptional, but forever inaccessible treasures.”

The simulated cavern is not only a stunning tribute to a place, but also to a moment. It celebrates the cold afternoon in December 1994 when three friends and weekend cavers—Jean-Marie Chauvet, Eliette Brunel and Christian Hillaire—followed an air current into an aperture in a limestone cliff, tunneled their way through a narrow passage, using hammers and awls to chip away at the rocks and stalactites that blocked their progress, and descended into a world frozen in time—its main entrance blocked off by a massive rock slide 29,000 years ago. Brunel, the first to wedge through the passage, glimpsed surreal crystalline deposits that had built up for millennia, then stopped before a pair of blurry red lines drawn on the wall to her right. “They have been here,” she shouted to her awe-struck companions.

The trio moved gingerly across the earthen floor, trying not to tread on the crystallized ashes from an ancient fire pit, gazing in wonder at hundreds of images. “We found ourselves in front of a rock wall covered entirely with red ocher drawings,” the cavers remembered in their brief memoir published last year. “The panel contained a mammoth with a long trunk, then a lion with red dots spattered around its snout in an arc, like drops of blood. We crouched on our heels, gazing at the cave wall, mute with stupefaction.”

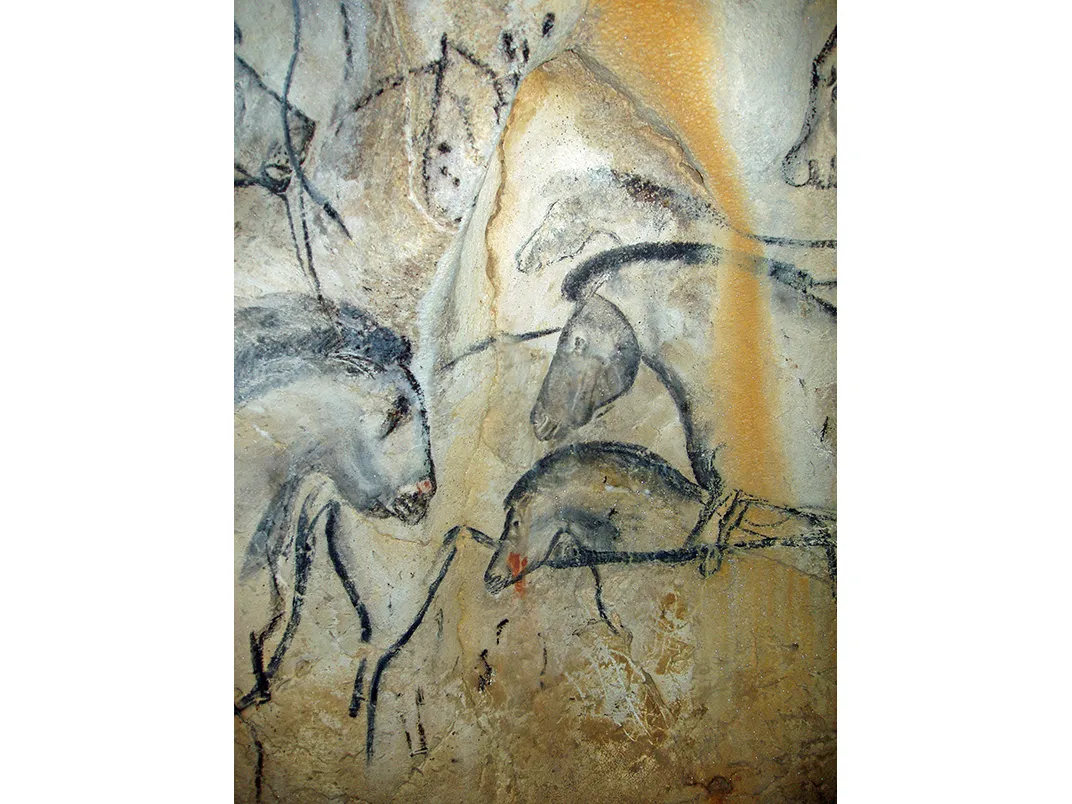

Spread out over six chambers spanning 1,300 feet were panels of lionesses in pursuit of great herbivores—including aurochs, the now-extinct ancestors of domestic cattle, and bison; engravings of owls and woolly rhinoceroses; a charcoal portrait of four wild horses captured in individualized profile, and some 400 other images of beasts that had roamed the plains and valleys in huge numbers during the ice age. With a skill never before seen in cave art, the artists had used the knobs, recesses and other irregularities of the limestone to impart a sense of dynamism and three-dimensionality to their galloping, leaping creatures. Later, Jean-Marie Chauvet would marvel at the “remarkable realism” and “aesthetic mastery” of the artworks they encountered that day.

Within months, Chauvet (the cave, officially Chauvet-Pont d’Arc, was named for its primary discoverer) would revolutionize our understanding of emerging human creativity. Radiocarbon dating conducted on 80 charcoal samples from the paintings determined that the majority of the works dated back 36,000 years—more than double the age of any comparable cave art yet uncovered. A second wave of Paleolithic artists, scientists would determine, entered the cave 5,000 years later and added dozens more paintings to the walls. Researchers were compelled to radically revise their estimates of the period when Homo sapiens first developed symbolic art and began to unleash the power of imagination. At the height of the Aurignacian period—between 40,000 and 28,000 years ago—when Homo sapiens shared the turf with the still-dominant Neanderthals, this artistic impulse may have signaled an evolutionary leap. While Homo sapiens were experimenting with perspective and creating proto-animation on the walls, their cousins, the Neanderthals, shuffling toward extinction, had not moved beyond the production of crude rings and awls. The finding also demonstrated that Paleolithic artists had painted in a consistent style, using similar techniques for 25,000 years—a remarkable stability that is the sign, Gregory Curtis wrote in The Cave Painters, his major survey of prehistoric art, of “a classical civilization.”

The Caverne du Pont d’Arc installation is the product of a bitter experience involving another irreplaceable treasure. The Lascaux Cave in the Dordogne region of southwestern France was, like Chauvet, discovered by serendipity: In September 1940, four teenage boys and their dog stumbled across it while searching for rumored buried treasure in the forest. The 650-foot-long subterranean complex contains 900 of the finest examples of prehistoric paintings and engravings ever seen, all dating back around 17,000 years. The cave’s undoing came after the French Ministry of Culture opened it to the public in 1948: Visitors by the thousands rushed in, destroying the fragile atmospheric equilibrium. A green slime of bacteria, fungi and algae formed on the walls; white-crystal deposits coated the frescoes. In 1963 alarmed officials sealed the cave and limited entry to scientists and other experts. But an irreversible cycle of decay had begun. Spreading fungus lesions—which cannot be removed without causing further damage—now cover many of the paintings. Moisture has washed away pigments and turned the white calcite walls a dull gray. In 2010, when then French President Nicolas Sarkozy and his wife, Carla Bruni-Sarkozy, toured the site on the 70th anniversary of its discovery, Laurence Léauté-Beasley, president of a committee that campaigns for the cave’s preservation, called the visit a “funeral service for Lascaux.”

Immediately upon Chauvet’s discovery—even before it was announced—French authorities installed a steel door at the entrance and imposed stringent access restrictions. In 2014, a total of 280 individuals—including scientists, specialists working on the simulation and conservators monitoring the cave—were allowed to enter, typically spending two hours in a single visit.

A few days after Christmas in 1994, Jean Clottes, a pre-eminent scholar of rock art and then an archaeology official in the French Ministry of Culture, received a call from a conservator, asking Clottes to rush to the Ardèche Gorge to verify a find. “I had my family coming; I asked whether I could do it after the New Year,” Clottes recalls one day at his home in Foix, in the Pyrenees south of Toulouse. “He said, ‘No, you’ve got to come right away. It looks like a big discovery. They say there are hundreds of images, lots of lions and rhinos.’ I thought that is bizarre, because representations of lions and rhinos are not very frequent in caves.”

Clottes arrived at the grotto and inched with great difficulty through the air shaft: “It was not horizontal. It sloped down, and then it turned, and then it sloped up. ” As he approached the walls in the darkness, peering at the images through his headlamp, Clottes could sense immediately that the works were genuine. He stared, enthralled, at the hand-size red dots that covered one wall, a phenomenon he had never observed before. “Later we found out that they were done by putting wet paint inside the hand, and applying the hand against the wall,” he says. “At the time, we didn’t know how they were made.” Clottes marveled at the verisimilitude of the wild horses, the vitality of the head-butting woolly rhinos, the masterful use of the limestone walls. “These were hidden masterpieces that nobody had laid eyes on for thousands and thousands of years, and I was the first specialist to see them,” he says. “I had tears in my eyes.”

In 1996, two years after his first visit to Chauvet, Clottes published a seminal work, The Shamans of Prehistory, co-written with the eminent South African archaeologist David Lewis-Williams, that presented new ideas about the origins of cave art. The world of Paleolithic man existed on two planes, the authors hypothesized, a world of sense and touch, and a spirit world that lay beyond human consciousness. Rather than serving as dwellings for ancient man, Clottes and his colleague contended, caves such as Chauvet—dark, cold, forbidding places—functioned as gateways to a netherworld where spirits were thought to dwell. Elite members of Paleolithic societies —probably trained in the representational arts—entered these caves for ritualistic communion with the spirits, reaching out to them through their drawings. “You needed torches, grease lamps and pigment to go inside the caves. It was not for everyone. It was an expedition,” Clottes told me.

As Clottes and his co-author interpreted it, the red-ocher handprints on the walls of Chauvet might well have represented attempts to summon the spirits out of the rock; the artists would likely have used the limestone wall’s irregularities not only to animate the animal’s features but also to locate their spirits’ dwelling places. Enigmatic displays found inside Chauvet—a bear cranium placed on an altarlike pedestal, a phallic column upon which a woman’s painted legs and vulva blend into a bison’s head—lend weight to the theory that these places held transformative power and religious significance. Clottes imagined that these primeval artists connected to the spirit world in an altered state of consciousness, much like the hallucinogen-induced trances achieved by modern-day shamans in traditional societies in South America, west Asia, parts of Africa, and Australia. He perceived parallels between the images that shamans see when hallucinating—geometric patterns, religious imagery, wild animals and monsters—and the images adorning Chauvet, Lascaux and other caves.

It was not surprising, says Clottes, that these early artists made the conscious choice to embellish their walls with wild animals, while almost entirely ignoring human beings. For Paleolithic man, animals dominated their environment, and served as sources of both sustenance and terror. “You must imagine the Ardèche Gorge of 30,000 years ago,” Clottes, now 81, says in his home study, surrounded by Tuareg knives and saddlebags, Central African masks, Bolivian cloth puppets and other mementos from his travels in search of ancient rock art. “In those days you might have one family of 20 people living there, the next family 12 miles away. It was a world of very few people living in a world of animals.” Clottes believes that prehistoric shamans invoked the spirits in their paintings not only to aid them on their hunts, but also for births, illnesses and other crises and rites of passage. “These animals were full of power, and the paintings are images of power,” he says. “If you get in touch with the spirit, it is not out of idle curiosity. You do it because you need their help.”

Clottes’ original interpretation of Paleolithic art was at once embraced and ridiculed by fellow scholars. One dismissed it as “psychedelic ravings.” Another titled his review of the Clottes-Lewis-Williams book, “Membrane and Numb Brain: A Close Look at a Recent Claim for Shamanism in Paleolithic Art.” One colleague berated him for “encouraging the use of drugs” by writing lyrically about the trancelike states of the Paleo shamans. “We were accused of all sorts of things, even of immorality,” Clottes tells me. “But altered states of consciousness are a fundamental part of us. It is a fact.”

Clottes found a champion in the German director Werner Herzog, who made him the star of his documentary about Chauvet, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, and popularized Clottes’ theories. “Will we ever be able to understand the vision of these artists across such an abyss of time?” Herzog asks, and Clottes, on camera, provides an answer. For the artists, “There [were] no barriers between the world where we are and the world of the spirits. A wall can talk to us, can accept us or refuse us,” he said. “A shaman can send his or her spirit to the world of the supernatural or can receive the visit inside him of supernatural spirits...you realize how different life must have been for those people from the way we live now.”

In the years since his theory of a prehistoric vision quest first stirred debate, Clottes has been challenged on other fronts. Archaeologists have insisted that the samples used to date the Chauvet paintings must have been contaminated, because no other artworks from that period have approached that level of sophistication. Declaring the paintings to be 32,000 years old was like claiming to have found “a Renaissance painting in a Roman villa,” scoffed British archaeologist Paul Pettit, who insisted they were at least 10,000 years younger. The findings “polarized the archaeological world,” said Andrew Lawson, another British archaeologist. But arguments for the accuracy of the dating got a boost four years ago, when Jean-Marc Elalouf at the Institute of Biology and Technology in Saclay, France, conducted DNA studies and radiocarbon dating of the remains of cave bears (Ursus spelaeus) that ventured inside the grotto to hibernate during the long ice age winters. Elalouf determined that the cave bear skeletal remains were between 37,000 and 29,000 years old. Humans and bears entered the cave on a regular basis—though never together—before the rock fall. “Then, 29,000 years ago, after the rock slide, they couldn’t get inside anymore,” says Clottes.

Paleontologists (who study animal remains inside the cave, mainly of bears but also wolves, ibexes and other mammals), geologists (who examine how the cave evolved and what this can tell us about prehistoric people’s actions inside it), art historians (who study the painted and engraved walls in all their detail) and other specialists visit Chauvet on a regular basis, adding to our understanding of the site. They have mapped every square inch with advanced 3-D technology, counted the bones of 190 cave bears and inventoried the 425 animal images, identifying nine species of carnivores and five species of ungulates. They have documented the pigments used—including charcoal and unhydrated hematite, a natural earth pigment otherwise known as red ocher. They have uncovered and identified the tools the cave artists employed, including brushes made from horse hair, swabs, flint points and lumps of iron oxides dug out of the ground that could be molded into a kind of hand-held, Paleolithic crayon. They have used geological analysis and a laser-based remote sensing technology to visualize the collapse of limestone slabs that sealed access to Chauvet Cave until its 1994 rediscovery.

One recent study, co-directed by Clottes, analyzed the faint traces left by human fingers on a decorated panel in the End Chamber. The fingers were pressed against the wall and moved vertically or horizontally against the soft limestone before the painter drew images of a lion, rhinoceros, bison and bear. Clottes and his co-researcher, Marc Azéma, theorize that the tracing was a shamanistic ritual intended to establish a link between the artist and the supernatural powers inside the rock. Prehistorian Norbert Aujoulat studied a single painting, Panel of the Panther, identified the tools used to create the masterwork and found other images throughout the cave that were produced employing the same techniques. Archaeologists Dominique Baffier and Valérie Feruglio have focused their research on the large red dots on the Chauvet walls, and determined that they were made by two individuals—a male who stood about 5-foot-9 and a female or adolescent—who coated their hands with red ocher and pressed their palms against the limestone.

Jean-Michel Geneste, Clottes’ successor as scientific director of Chauvet, leads two 40-person teams of experts into the grotto each year—in March and October—for 60 hours of research over 12 days. Geneste co-authored a 2014 study that analyzed a mysterious assemblage of limestone blocks and stalagmites in a side alcove. His team concluded that Paleolithic men had arranged some of the blocks, perhaps in the process of opening a conduit to paintings in other chambers, perhaps for deeper symbolic reasons. Geneste has also paid special attention to depictions of lions, symbols of power accorded a higher status than other mammals. “Some of the lion paintings are very anthropomorphic,” he observes, “with a nose and human profile showing an empathy between the artists and these carnivores. They are painted completely differently from other animals in Chauvet.”

When I arrived at the Caverne du Pont d’Arc for a preview that rainy morning this past December, I was skeptical. The installation’s concrete enclosure was something of an eyesore in an otherwise pristine landscape—like a football stadium plunked down at Walden Pond. I feared that a facsimile would reduce the miracle of Chauvet to a Disneyland or Madame Tussaud-style theme park—a tawdry, commercialized experience. But my hopes began to rise as we followed a winding pathway flanked by pines, offering vistas of forested hills at every turn. At the entrance to the recreated cave, a dark passage, the air was moist and cool—the temperature maintained at 53.5 degrees, just as in Chauvet. The rough, sloping rock faces, streaked with orange mineral deposits, and multi-spired stalactites hanging from the ceiling, felt startlingly authentic, as did the reproduced bear skulls, femurs and teeth littering the earthen floors. The paintings were copied using the austere palette of Paoleolithic artists, traced on surfaces that reproduced, bump for bump, groove for groove, the limestone canvas used by ancient painters.

The exactitude owed much to the participation of some of the most preeminent prehistoric cave experts in France, including Clottes and Geneste. The team painstakingly mapped every square inch of the real Chauvet by using 3-D models, then shrinking the projected surface area from 8,000 to 3,000 square meters. Architects suspended a frame of welded metal rods—shaped to digital coordinates provided by the 3-D model—from the roof of the concrete shell. They layered mortar over the metal cage to re-create the limestone inside Chauvet. Artists then applied pigments with brushes, mimicking the earth tones of the cave walls, based on studies conducted by geomorphologists at the University of Savoie in Chambery. Artists working in plastics created crystal formations and animal bones. Twenty-seven panels were painted on synthetic resin in studios in both Montignac, in the Dordogne; and in Toulouse. “We wanted the experience to resemble as closely as possible the feeling of entering the grotto,” artist Alain Dalis told me.

Twenty years to the day that Chauvet and his two companions first edged their way into the cave, Paulo Rodrigues and Charles Chauveau, conservators overseeing the site, are climbing a path beyond a vineyard through a forest of pine and chestnut toward the base of a limestone cliff perforated with grottoes. It’s a cold, misty morning in December, and wisps of fog drift over the neat rows of vines and the Ardèche River far below. The Pont d’Arc, the limestone arch that spans the river, lies obscured behind the trees. During the Aurignacian period, Rodrigues tells me, the vegetation was much sparser here, and the Pont d’Arc would have been visible from the rock ledge that we’re now walking on; from this angle the formation bears a striking resemblance to a mammoth. Many experts believe that early artists deliberately selected the Chauvet cave for their vision quests because of its proximity to the limestone monolith.

As I followed the conservators, I was retracing not only the route to the cave, but also events that have led to a bruising debate about who should have bragging rights to the cave’s discovery. The story begins on this footpath, in the spring of 1994, when a veteran spelunker and friend of Jean-Marie Chauvet, Michel Rosa, known to friends as Baba, initially detected air seeping from a small chamber blocked by stones. According to close friends of both men, it was Baba who suggested the airflow was coming from a cave hidden behind the rocks. Baba, they said, tried to climb into the hole, only to give up after reaching a stalactite he couldn’t move by hand. The aperture became known among spelunkers as Le Trou de Baba, or Baba’s Hole.

Chauvet has maintained that Rosa—a reclusive figure who has rarely spoken publicly about the case—lost interest in the site and moved on to explore other caves. Others insist that Baba had always planned to come back—and that Chauvet had cheated him out of the chance by returning, unannounced, with Eliette Brunel six months later. Chauvet violated a caver’s code of honor, says Michel Chabaud, formerly one of his closest friends. “On the level of morality,” he says, “Chauvet did not behave well.” Baba vanished into obscurity and Chauvet’s name was attached to one of the world’s greatest cultural treasures.

After following the path along the cliff, the conservators and I stop before a grotto used to store equipment and monitor the atmosphere inside Chauvet. “We are doing all we can to limit the human presence, so as not to alter this equilibrium,” says Chauveau, showing me a console with removable air-sample tubes that measure the level of radon, a colorless, odorless radioactive gas released from decaying uranium-ore deposits inside caves. “The goal is to keep the cave in the exact condition that it was found in 1994,” he adds. “We don’t want another Lascaux on our hands.” The two conservators make their way here weekly, checking for intruders, making certain that air filters and other equipment are running smoothly.

Afterward, we follow a wooden walkway, constructed in 1999, that leads to the Chauvet entrance. Rodrigues points to a massive slab of limestone, covered in moss, orange mineral deposits and weeds—“all of that rock slid down, and covered the original entrance.”

At last we arrive at a set of wooden steps and climb to the four-foot-high steel door that seals off the aperture. It is as far as I am permitted to go: The Culture Ministry bars anyone from entering the cave during the damp and cold Provençal winter, when carbon dioxide levels inside the grotto reach 4 percent of the total atmosphere, twice as high as the amount considered to be safe to breathe.

It was just a few dozen yards from this spot that another drama played out on the night of December 24, 1994—a story that has re-emerged in the public eye and renewed old grievances. At Chauvet’s invitation, Michel Chabaud and two other spelunkers, all close friends and occasional visitors to the Trou de Baba, entered the cave to share with the original three their exhilaration at the discovery. Six days after their find, Chauvet, Brunel and Hillaire had not yet explored every chamber. Chabaud and his two friends pushed into the darkness—and became the first humans in 30,000 years to penetrate the Gallery of the Lions, the End Chamber, where the finest drawings were found. “We saw paintings everywhere, and we went deeper and deeper,” Chabaud wrote in his diary that evening. “We were in a state of incredible excitement Everyone was saying, ‘incredible, this is the new Lascaux.’” Chabaud and his companions showed the chamber they discovered to Chauvet, he says, and asked for recognition of their role in the find. Chauvet brushed them off, saying dismissively, “You were only our guests.”

I caught up with the three original discoverers—or inventeurs, as the French often call them—a few days before this past Christmas in St. Remèze, a village of winding alleys and red-tile-roofed houses deep in the forests of the Ardèche Gorge. All had gathered in the courtyard of the Town Hall for the 20th anniversary celebration of their find. It had been a difficult week for them. The national press had picked up on the revived quarrel over the cave’s discovery. A headline in the French edition of Vanity Fair declared, “The Chauvet Cave and Its Broken Dreams.” New allegations were being aired, including a charge that one of the three discoverers, Christian Hillaire, had not even been at the cave that day.

The fracas was playing out against protracted haggling between the trio and the Caverne du Pont d’Arc’s financial backers. At stake was the division of profits from the sale of tickets and merchandise, a deal said to be worth millions. Chauvet and his companions had received $168,000 apiece from the French government as a reward for their discovery, and some officials felt the three did not deserve anything more. “They are just being greedy,” one official told me. (The Lascaux discoverers had never received a penny.) With negotiations stalled, the project’s backers had stripped the name “Chauvet” from the Caverne du Pont d’Arc facsimile—it was supposed to have been called the Caverne Chauvet-Pont d’Arc—and withdrawn invitations for the three to the opening. The dispute was playing into the hands of the inventeurs’ opponents. Pascal Terrasse of the Pont d’Arc project announced he was suspending talks with the trio because, he told Le Point newspaper, “I can’t negotiate with the people who aren’t the real discoverers.”

Christian Hillaire, stocky and rumpled, told me after weeks of what he deemed lies drummed up by a “cabal organized against us,” they could no longer remain silent. “We have always avoided making claims, even when we’re attacked,” said Eliette Brunel, a bespectacled, elegant and fit-looking woman, as we strolled down an alley in St. Remèze, her hometown, which was dead quiet in the wintry off-season. “But now, morally, we cannot accept what is happening.” Chauvet, a compact man with a shock of gray hair, said that the falling out with his former best friends still pained him, but he had no regrets for the way he had acted. “The visit [to the Chauvet Cave] on December 24th was a great convivial moment,” he said. “Everything that happened afterward was a pity. But we were there first, on the 18th of December. That can’t be forgotten. It’s sad that [our former friends] can no longer share this satisfying moment with us, but that was their choice.”

We walked together back to the Town Hall, where the celebrations had commenced. Volunteers in Santa hats served mulled wine to 50 neighbors and admirers of the cave explorers, who signed copies of a new book and posed for photos. “We’re among friends now,” Brunel told me. As the light faded and the temperature dropped, Chauvet addressed the gathering in the courtyard. He referred mockingly to the fact that he hadn’t been invited to the opening of the facsimile (“I’ll have to pay €8 like everyone else”) but insisted that he wasn’t going to be dragged into the controversy. “The important thing is that what we discovered inside that cave belongs to all of humanity, to our children,” he said, to applause, “and as for the rest of it, come what may.”

Indeed, all of the squabbling seemed to pale into insignificance as I stood in the End Chamber at the Caverne du Pont d’Arc, gazing through the murk. I studied one monumental panel, 36 feet long, drawn in charcoal. Sixteen lions on the far right sprang in pursuit of a panicking herd of buffalo. To the left, a pack of woolly rhinos thundered across the tableau. The six curving horns of one beast conveyed rapid movement—what Herzog had described as “a form of proto cinema.” A single rhino had turned to face the stampeding herd. I marveled at the artist’s interplay of perspective and action, half-expecting the menagerie to launch itself from the rock. I thought: They have been here.

Cave Art

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)