Frederick Douglass Thought This Abolitionist Was a ‘Vastly Superior’ Orator and Thinker

A new book offers the first full-length biography of newspaper editor, labor leader and minister Samuel Ringgold Ward

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/10/c2/10c2a775-8f06-4001-bcf5-eb76cdf678f2/ward.jpg)

Looking back over his many years in the trenches, fighting against the twin evils of slavery and discrimination, Frederick Douglass remembered a Free Soil Party meeting he attended in Buffalo, New York, with Samuel Ringgold Ward and some other African American activists and abolitionists. Ward, he recalled, attracted attention wherever he appeared:

As an orator and thinker, he was vastly superior, I thought, to any of us, and being perfectly black and of unmixed African descent, the splendors of his intellect went directly to the glory of [the] race. In depth of thought, fluency of speech, readiness of wit, logical exactness and general intelligence, Samuel R. Ward has left no successor among the colored men amongst us, and it was a sad day for our cause when he was laid low in the soil of a foreign country.

There is no better description of Ward and his contributions to the struggle for Black freedom, citizenship and equality. There is also that sad coda to Douglass’ reminiscence: Ward had since turned his back on the United States, ending his life in obscurity in Jamaica. That may explain why Ward, who gave up on America, has escaped the biographer’s gaze. Searching for an explanation of Ward’s later years, historian Tim Watson could do no better than call it “remarkable and strange.” He could have added “elusive.”

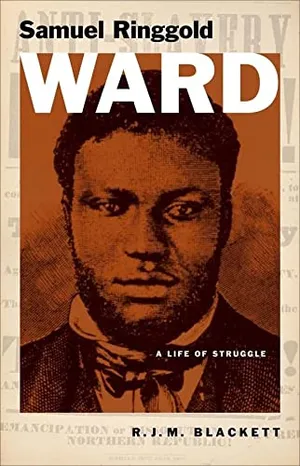

Samuel Ringgold Ward: A Life of Struggle

The rediscovery of a pivotal figure in Black history and his importance and influence in the struggle against slavery and discrimination

Ward was born enslaved on the Eastern Shore of Maryland in 1817. He and his parents escaped when he was a young child to rural southern New Jersey, where they settled among other fugitives from slavery in an area dominated by Quakers. Years later, the family moved to the relative safety and anonymity of New York City, where Ward attended the African Free School, whose alumni, including physician James McCune Smith, minister Alexander Crummell and abolitionist William Howard Day, would play prominent roles in the struggle for equal rights.

Ward felt the full force of American racism when a white mob attacked an antislavery meeting in New York City in 1834. It was, in a way, a baptism of fire and an introduction to the struggle that would come to dominate his life for the next 20 years. He was ordained as a Congregationalist minister in 1839. Two years later, he accepted an offer to minister to an all-white congregation in South Butler, New York.

A few years later, Ward moved to a larger, also all-white congregation in Cortland, New York. It was during this period that he established himself as one of the leading figures in the struggle against slavery and discrimination in the U.S. He was employed as a lecturer for the American Antislavery Society, and when the society split in 1840, Ward threw in his lot with the new American and Foreign Antislavery Society, believing that the Constitution and involvement in the political process offered the best means of ending slavery.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c5/ef/c5ef9008-8c94-43d2-81a7-4b43a1602451/samuel_ringgold_ward.png)

He was a mainstay of the Liberty Party, which nominated him for a state assembly seat in 1848. Two days later, Ward issued his manifesto. He opposed war with Mexico and the expansion of slavery in any of the territories gained by the U.S. He condemned the clause in the 1846 Wilmot Proviso that allowed for the return of escaped slaves; called for the abolition of slavery in Washington, D.C.; opposed the domestic slave trade; insisted on the recognition of Haitian independence; demanded the prohibition of alcohol; and pledged to fight for the full restoration of the right to vote for New York’s 40,000 Black citizens. The manifesto tells us much of what we need to know about Ward’s commitment to the cause of freedom. The following year, he started his first newspaper, the True American. He merged it with Stephen Myers’ Northern Star and Freeman’s Advocate soon after to form the Impartial Citizen, which would become the major organ of the Liberty Party.

The anti-abolitionist riots in New York City and the constant struggle against racism wore on Ward and his contemporaries in ways that are not always easy to discern. There were moments when Ward considered a future in a place where the pall of racism was not so heavy. In 1839, he thought seriously about moving to Trinidad, which had officially ended slavery the previous year, but in the end, he chose to stay and fight.

Ward faced constant reminders of the growing political influence of American slavery. The Supreme Court’s decision in the 1842 Prigg v. Pennsylvania case, which allowed states to forbid authorities from aiding slave catchers but paved the way for stricter federal legislation regarding fugitives from slavery, weighed heavily on him. It coincided with his discovery that he had been born enslaved, a fact his parents had kept from him. He was now no longer a free Black man, as he had thought, but a fugitive, a man without free papers and vulnerable to capture and return to Maryland—a man, in effect, without a country.

Ward took the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 personally, as an existential threat. His public defiance of the law made him even more vulnerable. The day Ward arrived in Syracuse in fall 1851, after a grueling tour of the American West, the city was thrown into turmoil with word that Jerry McHenry, an enslaved man from Missouri, had been captured and was being held in a local jail pending a rendition hearing. A few minutes after Ward and others visited McHenry in his cell, a crowd stormed the jail, freeing the prisoner and sending him to Canada, which had abolished slavery in 1834. Fearing arrest, Ward followed McHenry north.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a7/f1/a7f1fd9c-067c-4c16-a266-366c7f8a4063/samuel_ringgold_ward.jpeg)

Ward would never return. He did in Canada what he had done in the U.S.: He became a leading voice in the newly formed Antislavery Society of Canada, which devoted much of its energy and resources to providing for the rising number of fugitives from slavery who were entering the country in the wake of the 1850 legislation. He was also one of the founding editors of the Provincial Freeman, whose first edition appeared in March 1853.

Ward left soon after on a tour of Britain to raise funds for the society, leaving the newspaper in the capable hands of publisher Mary Ann Shadd Cary. He was a rousing success wherever he went, raising a substantial sum of money for the society and promoting the cause of abolition in the U.S. He lectured widely on slavery, temperance, peace and missionary causes. He sometimes found himself at loggerheads with British supporters of the American Antislavery Society, who disagreed over the best way to end slavery, but by and large, he stayed clear of the controversies that continued to beset the movement. Like many other Black Americans who visited Britain, Ward moved in some heady social circles, rubbing elbows with lords and ladies who invited him to social events where he was lionized. They were fascinated by his color and size: He was a very dark-skinned man, standing over six feet tall and weighing, one besotted admirer estimated, “16 stone” (224 pounds).

Fascination with Ward’s physical features led one fan to observe that his circle of chin whiskers could be seen only at close quarters. What such a description said about Ward’s relationship with the observer one can only guess. Ward enjoyed the adulation yet never missed an opportunity to remind his audiences of his passionate commitment to the end of slavery and the elevation of his people. “I am devoted to [Black people],” he told his listeners at a meeting of the Colonial Missionary Society. “I have none of the prejudices against their color that some people have; I married a Black woman.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b9/b9/b9b945ed-e3c3-4579-855f-337c014ed8ef/henry_highland_garnet_by_james_u_stead_crop.png)

Though he wasn’t closely allied with the Free-Produce Movement in the U.S., Ward threw his weight behind the boycott effort’s revival while in Britain. The cultivation of sugar, cotton and other agricultural staples on which the British economy relied, its supporters maintained, could be more cheaply produced by free labor in Britain’s West Indian colonies, reducing the country’s reliance on produce grown by enslaved people and thus helping to undermine slavery where it still existed.

William Burnley, the most prolific enslaver in Trinidad at the time of emancipation, argued that freedmen in places such as the West Indies needed a guiding and helping hand if they were to succeed. Ward’s cousin Henry Highland Garnet had accepted an appointment in Sterling, Jamaica, as a missionary of the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland just before Ward arrived in London. Ward would soon follow. John Chandler, a Quaker who owned land in Jamaica, offered Ward 50 acres on the understanding he would raise crops for export. Success, Ward and his benefactor hoped, would attract Black settlers from the U.S., as well as encourage the cultivation of staples by freedmen on the island. The fact that Ward had little experience as an agriculturalist did not augur well for the venture.

Before sailing for Jamaica, Ward published his Autobiography of a Fugitive Negro: His Antislavery Labors in the United States, Canada and England. It took him mere weeks, cloistered in his hotel room, to complete the lengthy manuscript. It was a remarkable feat of endurance and application. The book, as the title suggests, is divided into three parts: his American years, his brief stay in Canada and his tour of Britain. As such, it is an invaluable source of information on his activities in the years up to 1855, when he left London for Jamaica.

We know little about Ward’s time in Jamaica. On arrival, he settled in Kingston, where he became involved in the Baptist church. Not much was heard from him until 1866, in the months following the Morant Bay Rebellion of October 1865. Led by Paul Bogle, a Black small landowner, and supported by George William Gordon, a Black member of the local assembly, the rebellion was the most consequential political event in the years since emancipation in 1838. It started as a protest by peasants demanding more land, a demand the authorities resisted. Demonstrations outside of a local courthouse turned violent when the mayor called out the militia. Shots were fired, and the demonstrators retreated, only to return and set fire to the courthouse. That set in motion a rebellion resulting in the loss of scores of lives. Both Bogle and Gordon were captured and summarily executed.

In a short pamphlet published in early 1866, and in testimony before a commission sent out to investigate the causes of the rebellion, Ward denounced the leaders of the uprising and supported the actions of the governor. His position has continued to confound historians. Here was a proud Black man, who had made much of his attachment to and support of the rights of Black people, a man who in the U.S. was a driving force in the movement to eliminate slavery and discrimination, taking the side of white colonists in their efforts to deny the aspirations of Black Jamaicans. We know little more of Ward’s life in Jamaica.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/de/5a/de5a1bf0-cb44-4805-89e8-d282cc60593e/james_mccune_smith.jpeg)

If chronology is the biographer’s best friend, then gaps in the timeline are their worst enemies. The many lacunae in Ward’s life may be the reason there has never before been a full-blown biography of a person many contemporaries considered one of the giants of his era. Ronald K. Burke provided a few brief introductory chapters in his study of Ward’s rhetoric, published in 1995. Jeffrey Kerr-Ritchie has written several informative essays that attempt to locate changes in Ward’s ideology. Watson has provided an informed analysis of what he calls Ward’s “remarkable and strange career” in Jamaica.

The present study is the first attempt at a traditional biography. But the gaps are daunting. In his foreword to the 1970 edition of Ward’s autobiography, Vincent Harding pointed to a couple of the major gaps in Ward’s life story. There was little information on his early life and his marriage, and there was next to nothing on his involvement with the Liberty Party. These and other events, Harding writes, slip by in Ward’s autobiography “with almost frustrating speed.”

At the time, Harding was amazed by how little was known of Ward. What historians did know, he writes, was “at once enigmatic and elusive.” Since then, some of those gaps have been filled in, thanks largely to the work of C. Peter Ripley and his editorial staff, whose microfilm and published volumes, The Black Abolitionist Papers, collected and reprinted many of Ward’s major speeches, editorials and letters. Much, however, remains unknown. We know next to nothing about Ward’s pastorate in Cortland. We know a little more about his first church in Kingston but nothing about his subsequent pastorates. His death remains a lasting mystery. Harding calls it an example of the “kind of imploding alien death in which Black Americans have become so skilled.”

Despite many helping and generous hands, elements of Ward’s life continue to defy the best efforts of the biographer. All things considered, this is as full a story as is possible of a life that both inspires and frustrates. As African Free School classmate Smith said of Ward, he was “‘the ablest thinker on his legs’ which Anglo-Africa has produced, whose powerful eloquence, brilliant repartee and stubborn logic are as well known in England as in the United States.”

Excerpted from Samuel Ringgold Ward: A Life of Struggle by R.J.M. Blackett, the first installment in Yale University Press’ Black Lives series. Copyright © 2023 by R.J.M. Blackett.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rjm.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rjm.png)