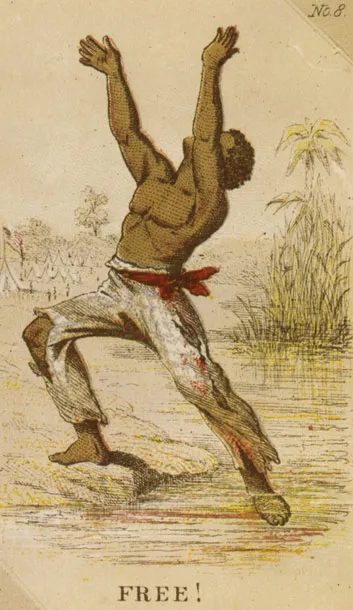

Free at Last

A new museum celebrates the Underground Railroad, the secret network of people who bravely led slaves to liberty before the Civil War

The phone rang one drizzly morning in Carl Westmoreland’s office overlooking the gray ribbon of the Ohio River and downtown Cincinnati. It was February 1998. Westmoreland, a descendant of slaves, scholar of African-American history and former community organizer, had recently joined the staff of the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. Then still in the planning stages, the center, which opened this past August in Cincinnati, is the nation’s first institution dedicated to the clandestine pre-Civil War network that helped tens of thousands of fugitive slaves gain their freedom.

The caller, who identified himself as Raymond Evers, claimed that a 19th-century “slave jail” was located on his property in northern Kentucky; he wanted someone to come out to look at it. As word of the center had gotten around, Westmoreland had begun to receive a lot of calls like this one, from individuals who said their house contained secret hiding places or who reported mysterious tunnels on their property. He had investigated many of these sites. Virtually none turned out to have any connection with the Underground Railroad.

“I’ll call you back tomorrow,” Westmoreland said.

The next day, his phone rang again. It was Evers. “So when are you coming out?” he asked. Westmoreland sighed. “I’m on my way,” he said.

An hour later, Westmoreland, a wiry man then in his early 60s, was slogging across a sodden alfalfa pasture in Mason County, Kentucky, eight miles south of the Ohio River, accompanied by Evers, 67, a retired businessman. The two made their way to a dilapidated tobacco barn at the top of a low hill.

“Where is it?” Westmoreland asked.

“Just open the door!” Evers replied.

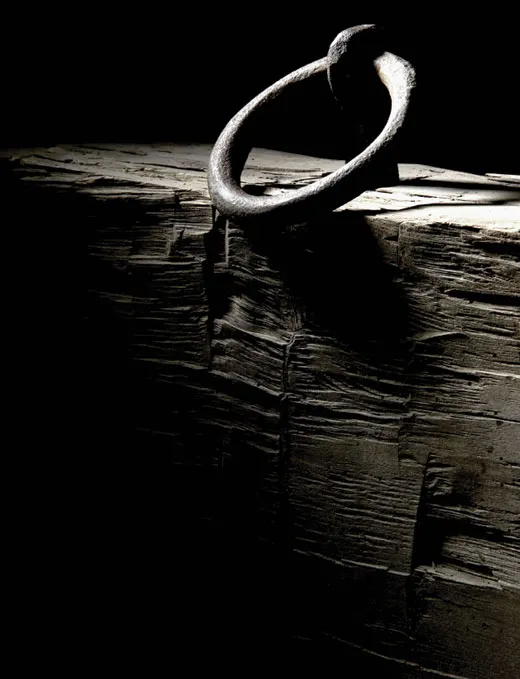

In the darkened interior, Westmoreland made out a smaller structure built of rough-hewn logs and fitted with barred windows. Fastened to a joist inside the log hut were iron rings: fetters to which manacled slaves had once been chained. “I felt the way I did when I went to Auschwitz,” Westmoreland later recalled. “I felt the power of the place— it was dark, ominous. When I saw the rings, I thought, it’s like a slave-ship hold.”

At first, Westmoreland had difficulty tracking down the history of the structure, where tobacco, corn and farm machinery had been stored for decades. But eventually Westmoreland located a MasonCounty resident who had heard from his father, who had heard from his grandfather, what had gone on in the little enclosure. “They chained ’em up over there, and sold ’em off like cattle,” the MasonCounty man told Westmoreland.

At Westmoreland’s urging, the FreedomCenter accepted Evers’ offer to donate the 32- by 27-foot structure. It was dismantled and transported to Cincinnati; the total cost for archaeological excavation and preservation was $2 million. When the FreedomCenter opened its doors on August 23, the stark symbol of brutality was the first thing that visitors encountered in the lofty atrium facing the Ohio River. Says Westmoreland: “This institution represents the first time that there has been an honest effort to honor and preserve our collective memory, not in a basement or a slum somewhere, but at the front door of a major metropolitan community.”

By its own definition a “museum of conscience,” the 158,000-square-foot copper-roofed structure hopes to engage visitors in a visceral way. “This is not a slavery museum,” says executive director Spencer Crew, who moved to Cincinnati from Washington, D.C., where he was director of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History. “Rather, it is a place to engage people on the subject of slavery and race without finger-pointing. Yes, the center shows that slavery was terrible. But it also shows that there were people who stood up against it.”

Visitors will find, in addition to the slave jail, artifacts including abolitionists’ diaries, wanted posters, ads for runaways, documents granting individual slaves their freedom and newspapers such as William Lloyd Garrison’s militant Liberator, the first in the United States to call for immediate abolition. And they will encounter one of the most powerful symbols of slavery: shackles. “Shackles exert an almost mystical fascination,” says Rita C. Organ, the center’s director of exhibits and collections. “There were even small-sized shackles for children. By looking at them, you get a feeling of what our ancestors must have felt—suddenly you begin to imagine what it was like being huddled in a coffle of chained slaves on the march.”

Additional galleries relate stories of the central figures in the Underground Railroad. Some, like Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, are renowned. Many others, such as John P. Parker, a former slave who became a key activist in the Ohio underground, and his collaborator, abolitionist John Rankin, are little known.

Other galleries document the experiences of present-day Americans, people like Laquetta Shepard, a 24-year-old black Kentucky woman who in 2002 walked into the middle of a Ku Klux Klan rally and shamed the crowd into dispersing, and Syed Ali, a Middle Eastern gas station owner in New York City who prevented members of a radical Islamic group from setting fire to a neighborhood synagogue in 2003. Says Crew, “Ideally, we would like to create modern-day equivalents of the Underground Railroad conductors, who have the internal fortitude to buck society’s norms and to stand up for the things they really believe in.”

The center’s concept grew out of a tumultuous period in the mid-1990s when Cincinnati was reeling from confrontations between the police and the African-American community and when Marge Schott, then the owner of the Cincinnati Reds, made comments widely regarded as racist. At a 1994 meeting of the Cincinnati chapter of the National Conference of Christians and Jews, its then-director, Robert “Chip” Harrod, proposed the idea of a museum devoted to the Underground Railroad. Since then, the center has raised some $60 million from private donations and another $50 million from public sources, including the Department of Education.

The term underground railroad is said to derive from the story of a frustrated slave hunter who, having failed to apprehend a runaway, exclaimed, “He must have gone off on an underground road!” In an age when smoke-belching locomotives and shining steel rails were novelties, activists from New York to Illinois, many of whom had never seen an actual railroad, readily adopted its terminology, describing guides as “conductors,” safe houses as “stations,” horsedrawn wagons as “cars,” and fugitives as “passengers.”

Says Ira Berlin, author of Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America: “The Underground Railroad played a critical role, by making the nature of slavery clear to Northerners who had been indifferent to it, by showing that slaves who were running away were neither happy nor well-treated, as apologists for slavery claimed. And morally, it demonstrated the enormous resiliency of the human spirit in the collaboration of blacks and whites to help people gain their freedom.”

Thanks to the clandestine network, as many as 150,000 slaves may have found their way to safe havens in the North and Canada. “We don’t know the total number and we will probably never know,” says James O. Horton, a professor of American studies and history at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. “Part of the reason is that the underground was so successful: it kept its secrets well.”

As the nation’s second great civil disobedience movement— the first being the actions, including the Boston Tea Party, leading to the American Revolution—the Underground Railroad engaged thousands of citizens in the subversion of federal law. The movement provoked fear and anger in the South and prompted the enactment of draconian legislation, including the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, which required Northerners to cooperate in the capture of escaped slaves. And at a time when proslavery advocates insisted that blacks were better off in bondage because they lacked the intelligence or ability to take care of themselves, it also gave many African-Americans experience in political organizing and resistance.

“The Underground Railroad symbolized the intensifying struggle over slavery,” says Berlin. “It was the result of the ratcheting up of the earlier antislavery movement, which in the years after the American Revolution, had begun to call for compensated emancipation and gradualist solutions to slavery.” In the North, it brought African-Americans, often for the first time, into white communities where they could be seen as real people, with real families and real feelings. Ultimately, Berlin says, “the Underground Railroad forced whites to confront the reality of race in American society and to begin to wrestle with the reality in which black people lived all the time. It was a transforming experience.”

For blacks and whites alike the stakes were high. Underground agents faced a constant threat of punitive litigation, violent reprisal and possible death. “White participants in the underground found in themselves a depth of humanity that they hadn’t realized they had,” says Horton. “And for many of them, humanity won out over legality.” As New York philanthropist Gerrit Smith, one of the most important financiers of the Underground Railroad, put it in 1836, “If there be human enactments against our entertaining the stricken stranger—against our opening our door to our poor, guiltless, and unaccused colored brother pursued by bloodthirsty kidnappers—we must, nevertheless, say with the apostle: ‘We must obey God rather than man.’ ”

From the earliest years of American bondage—the Spanish held slaves in Florida in the late 1500s; Africans were sold to colonists at Jamestown in 1619—slaves had fled their masters. But until British Canada and some Northern states—including Pennsylvania and Massachusetts—began abolishing slavery at the end of the 18th century, there were no permanent havens for fugitives. A handful of slaves found sanctuary among several Native American tribes deep in the swamps and forests of Florida. The first coordinated Underground Railroad activity can be traced to the early 19th century, perhaps when free blacks and white Quakers began to provide refuge for runaways in and around Philadelphia, or perhaps when activists organized in Ohio.

The process accelerated throughout the 1830s. “The whole country was like a huge pot in a furious state of boiling over,” recalled Addison Coffin in 1897. Coffin served as an underground conductor in North Carolina and Indiana. “It was almost universal for ministers of the gospel to run into the subject in all their sermons; neighbors would stop and argue pro and con across the fence; people traveling along the road would stop and argue the point.” Although abolitionists initially faced the contempt of a society that largely took the existence of slavery for granted, the underground would eventually count among its members Rutherford B. Hayes, the future president, who as a young lawyer in the 1850s defended fugitive slaves; William Seward, the future governor of New York and secretary of state, who provided financial support to Harriet Tubman and other underground activists; and Allan Pinkerton, founder of the Pinkerton Detective Agency, who in 1859 helped John Brown lead a band of fugitive slaves out of Chicago and on to Detroit, bound for Canada. By the 1850s, the underground ranged from the northern borders of states including Maryland, Virginia and Kentucky to Canada and numbered thousands among its ranks from Delaware to Kansas.

But its center was the Ohio River Valley, where scores of river crossings served as gateways from slave states to free and where, once across the Ohio, fugitives could hope to be passed from farm to farm all the way to the Great Lakes in a matter of days.

In practice, the underground functioned with a minimum of central direction and a maximum of grass-roots involvement, particularly among family members and church congregations. “The method of operating was not uniform but adapted to the requirements of each case,” Isaac Beck, a veteran of Underground Railroad activity in southern Ohio, would recall in 1892. “There was no regular organization, no constitution, no officers, no laws or agreement or rule except the ‘Golden Rule,’ and every man did what seemed right in his own eyes.” Travel was by foot, horseback or wagon. One stationmaster, Levi Coffin, an Indiana Quaker and Addison’s uncle, kept a team of horses harnessed and a wagon ready to go at his farm in Newport (now Fountain City), Indiana. When additional teams were needed, Coffin wrote in his memoir, posthumously published in 1877, “the people at the livery stable seemed to understand what the teams were wanted for, and they asked no questions.”

On occasion, fugitives might be transported in hearses or false-bottomed wagons, men might be disguised as women, women as men, blacks powdered white with talc. The volume of underground traffic varied widely. Levi Coffin estimated that during his lifetime he assisted 3,300 fugitives— some 100 or so annually—while others, who lived along more lightly traveled routes, took in perhaps two or three a month, or only a handful over several years.

One of the most active underground centers—and the subject of a 15-minute docudrama, Brothers of the Borderland, produced for the Freedom Center and introduced by Oprah Winfrey—was Ripley, Ohio, about 50 miles east of Cincinnati. Today, Ripley is a sleepy village of two- and three-story 19thcentury houses nestled at the foot of low bluffs, facing south toward the Ohio River and the cornfields of Kentucky beyond. But in the decades preceding the Civil War, it was one of the busiest ports between Pittsburgh and Cincinnati, its economy fueled by river traffic, shipbuilding and pork butchering. To slave owners, it was known as “a black, dirty Abolition hole”— and with good reason. Since the 1820s, a network of radical white Presbyterians, led by the Rev. John Rankin, a flinty Tennessean who had moved north to escape the atmosphere of slavery, collaborated with local blacks on both sides of the river in one of the most successful underground operations.

The Rankins’ simple brick farmhouse still stands on a hilltop. It was visible for miles along the river and well into Kentucky. Arnold Gragston, who as a slave in Kentucky ferried scores of fugitives across the then 500- to 1,500-foot-wide Ohio River, later recalled that Rankin had a “lighthouse in his yard, about thirty feet high.”

Recently, local preservationist Betty Campbell led the way into the austere parlor of the Rankin house, now a museum open to the public. She pointed out the fireplace where hundreds of runaways warmed themselves on winter nights, as well as the upstairs crawl space where, on occasion, they hid. Because the Rankins lived so close to the river and within easy reach of slave hunters, they generally sheltered fugitives only briefly before leading them on horseback along an overgrown streambed through a forest to a neighboring farmhouse a few miles north.

“The river divided the two worlds by law, the North and the South, but the cultures were porous,” Campbell said, gazing across the river’s gray trough toward the bluffs of Kentucky, a landscape not much altered since the mid-19th century. “There were antislavery men in Kentucky, and also proslavery men here in Ohio, where a lot of people had Southern origins and took slavery for granted. Frequently, trusted slaves were sent from Kentucky to the market at Ripley.”

For families like the Rankins, the clandestine work became a full-time vocation. Jean Rankin, John’s wife, was responsible for seeing that a fire was burning in the hearth and food kept on the table. At least one of the couple’s nine sons remained on call, prepared to saddle up and hasten his charges to the next way station. “It was the custom with us not to talk among ourselves about the fugitives lest inadvertently a clue should be obtained of our modus operandi,” the Rankins’ eldest son, Adam, wrote years later in an unpublished memoir. “ ‘Another runaway went through at night’ was all that would be said.”

One Rankin collaborator, Methodist minister John B. Mahan, was arrested at his home and taken back to Kentucky, where after 16 months in jail he was made to pay a ruinous fine that impoverished his family and likely contributed to his early death. In the summer of 1841, Kentucky slaveholders assaulted the Rankins’ hilltop stronghold. They were repulsed only after a gun battle that left one of the attackers dead. Not even the Rankins would cross the river into Kentucky, where the penalty for “slave stealing” was up to 21 years’ imprisonment. One Ripley man who did so repeatedly was John P. Parker, a former slave who had bought his freedom in Mobile, Alabama; by day, he operated an iron foundry. By night, he ferried slaves from Kentucky plantations across the river to Ohio. Although no photograph of Parker has survived, his saga has been preserved in a series of interviews recorded in the 1880s and published in 1996 as His Promised Land: The Autobiography of John P. Parker.

On one occasion, Parker learned that a party of fugitives, stranded after the capture of their leader, was hiding about 20 miles south of the river. “Being new and zealous in this work, I volunteered to go to the rescue,” Parker recalled. Armed with a pair of pistols and a knife, and guided by another slave, Parker reached the runaways at about dawn. He found them hidden in deep woods, paralyzed with fear and “so badly demoralized that some of them wanted to give themselves up rather than face the unknown.” Parker led the ten men and women for miles through dense thickets.

With slave hunters closing in, one of the fugitives insisted on setting off in search of water. He had gone only a short way before he came hurtling through the brush, pursued by two white men. Parker turned to the slaves still in hiding. “Drawing my pistol,” he recalled, “I quietly told them that I would shoot the first one that dared make a noise, which had a quieting effect.” Through thickets, Parker saw the captured slave being led away, his arms tied behind his back. The group proceeded to the river, where a patroller spotted them.

Though the lights of Ripley were visible across the water, “they might as well have been [on] the moon so far as being a relief to me,” Parker recalled. Bloodhounds baying in their ears, the runaways located a rowboat quickly enough, but it had room for only eight people. Two would have to be left behind. When the wife of one of the men picked to stay behind began to wail, Parker would recall, “I witnessed an example of heroism that made me proud of my race.” One of the men in the boat gave up his seat to the woman’s husband. As Parker rowed toward Ohio and freedom, he saw slave hunters converge on the spot where the two men had been left behind. “I knew,” he wrote later, “the poor fellow had been captured in sight of the Promised Land.”

Parker carried a $2,500 price on his head. More than once, his house was searched and he was assaulted in the streets of Ripley. Yet he estimated that he managed to help some 440 fugitives to freedom. In 2002, Parker’s house on the Ripley waterfront—restored by a local citizens’ group headed by Campbell—opened to the public.

On a clear day last spring, Carl Westmoreland returned to the Evers farm. Since his first visit, he had learned that the slave jail had been built in the 1830s by a prosperous slave trader, John Anderson, who used it to hold slaves en route by flatboat to the huge slave market at Natchez, Mississippi, where auctions were held several times a year. Anderson’s manor house is gone now, as are the cabins of the slaves who served in his household, tended his land and probably even operated the jail itself.

“The jail is a perfect symbol of forgetting,” Westmoreland said at the time, not far from the slave trader’s overgrown grave. “For their own reasons, whites and blacks both tried to forget about that jail, just as the rest of America tried to forget about slavery. But that building has already begun to teach, by causing people to go back and look at the local historical record. It’s doing its job.” Anderson died in 1834 at the age of 42. Westmoreland continued: “They say that he tripped over a grapevine and fell onto the sharp stump of a cornstalk, which penetrated his eye and entered his brain. He was chasing a runaway slave.”