The U.S. Government’s Failed Attempt to Forge Unity Through Currency

In the late 1890s, the Bureau of Printing and Engraving tried to bridge the divide between silver and gold with a series of educational paper certificates

:focal(392x335:393x336)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9a/4c/9a4c80da-975d-4a6c-a9b0-35fd9572721d/silver.jpg)

Momentum for the “Tubman Twenty” comes at a time when Americans are reexamining foundational values of equality and democracy. President Joe Biden’s inaugural address urged national unity to heal political and social rifts, and his push to get the project—in the works since 2015 to replace Andrew Jackson’s portrait with Harriet Tubman’s on the $20 bill—back on track supposedly helps do just that.

This is not the first attempt to use currency to forge a national identity by commemorating a shared heritage. An earlier experiment 125 years ago attempted to do the same. But—spoiler alert—it failed in every sense.

The United States introduced silver certificates in 1878, at a time when the meaning of money was up for grabs. In the late 1890s, the nation was in the early process of transforming from a rural agrarian society into an industrialized, urbanized empire teeming with immigrants. But growing pains brought an identity crisis; new peoples, cultures, technologies, and work habits challenged the status quo, exposing political, social, and class conflicts that came to a head in the 1896 presidential election.

The free silver movement—to allow for unfettered silver coinage alongside the gold standard—reflected these divides. Proponents, many of whom were Western farmers and miners, believed free silver would expand the money supply for the poor. But gold supporters—often situated in Eastern metropolises—saw free silver as an attack on the country’s financial lifeblood, their own fortunes, and their class standing as sophisticated, urbane elites. The Secretary of the Treasury at the time, John G. Carlisle, supported gold, but recognized silver as “poor man’s money” and, with enthusiastic support from the Chief of the Bureau of Engraving, Claude M. Johnson, authorized a prestigious, artistic, “educational” series of silver certificates as a form of celebratory nationalism.

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing commissioned publicly acclaimed muralists William H. Low, Edwin Blashfield, and Walter Shirlaw, who had decorated government buildings and represented American art in international expos, to design the denominations. “It certainly would, from an artistic standpoint, be commencing at the very root to put a work of art in the hands of every man who buys a loaf of bread,” Low commented in 1893.

Low glorified a collective American past by portraying the Constitution as a civics lesson for the nation’s children. In his $1 certificate, entitled History Instructing Youth, Low depicted the Washington, D.C., skyline behind “History,” personified as a goddess, who is pointing at the Constitution to enlighten a boy. The reverse features George and Martha Washington. It’s a reflection of the time’s child savers movement—whereby white, middle-class philanthropists assimilated immigrant and lower-class children into productive workers and good citizens.

The theme of youth and citizenship reflected the free silver position. Coin’s Financial School, a popular booklet starring a young financier named Coin, differentiated democratic silver from aristocratic gold: “One was the money of the people—the other, of the rich.” In its pages, gold bugs like banker Lyman Gage, who detested silver and would succeed Carlisle as Secretary of the Treasury, were won over by Coin’s persuasive messaging and by the youth who delivered it.

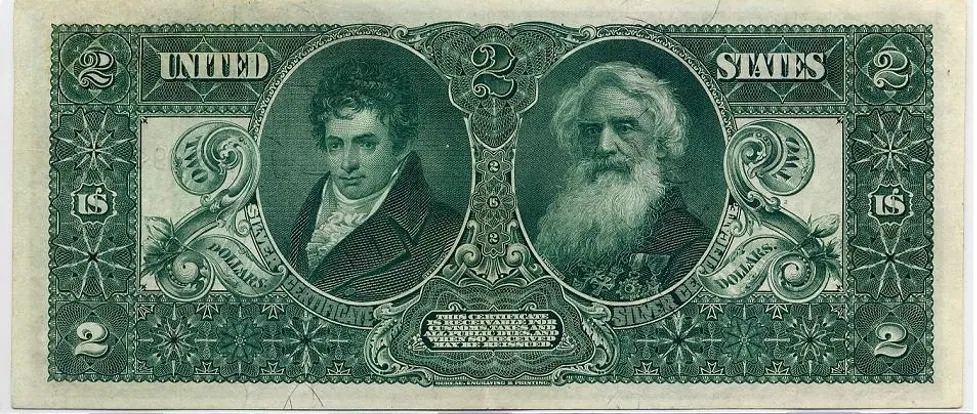

While the $1 certificate glorified the past, the $2 and $5 certificates highlighted technological and national progress. Edwin Blashfield’s Science Presenting Steam and Electricity to Commerce and Manufacture was a paean to industrialization. “Steam” and “Electricity” are children who join the adults, “Commerce” and “Manufacture.” Their proud fathers, inventors Robert Fulton (the steamboat) and Samuel Morse (the telegraph), preside from the reverse. The $5 certificate, Walter Shirlaw’s “America,” celebrated Americanism’s triumphs abroad. The figure of “America” wields Thomas Edison’s lightbulb to (en)lighten the world, and on the reverse, generals Ulysses Grant and Philip Sheridan watch the emergence of empire.

One newspaper gushed over the “educational value [in] that every man or child who possesses even a dollar will be attracted by the new design and will seek to learn their meanings.” Presumably, the bearers—ignorant immigrants and cynical citizens—would congeal into a cohesive American identity. But these certificates did the opposite.

First came a moral outcry against the art itself. Coin collector Gene Hessler asserts that anti-vice crusader Anthony Comstock “demanded the recall of these dirty dollars because of the lewd unclothed females.” The Bureau, in response, proactively modified the designs in accordance with good taste. For the $5 note, engravers extended the togas’ flowing drapery over America’s cleavage and the other bared bodies for the 1897 re-issue. Bureau chief engraver Thomas Morris also fretted over the prep work for the $10 note, bearing Shirlaw’s “Agriculture and Forestry”: “I fear the result of the criticism that will be made upon the figure of a man and woman almost nude in the centre.” Morris ultimately needed not worry; the $10 certificate never saw print.

The “dirty dollars” rhetoric also extended to skin color and the contemporary nativist fears over an exploding immigrant population. Gold bugs argued that silver watered down gold and the U.S. money supply, which extended to immigrants supposedly polluting American citizenship. As historian Michael O’Malley observes, gold bugs saw free silver as a plot sponsored by immigrants and silver miners in India, China and Mexico to take over the economy. Free silver paralleled the nativist fears that foreign silver—and foreign labor—cheapened native-born Americans, devaluing their work and money. While Carlisle’s theme of education indirectly addressed these fears by using nation-building as the certificates’ main theme, many gold bugs continued to openly associate free silver with foreigners, anarchists and agitators they viewed as inimical to national values and their livelihood.

For gold bugs, the “outside” threat also came from out West. Eastern moneymen, especially, deemed free silver as a sign of backwardness from the proverbial “sticks.” One naysayer singled out the Coin’s Financial School booklet for having a 12-year-old dare to instruct his elders in finance: “The immaturity of the instructor shines in all he says.” The critic sneered that those “who know something of the subject are amazed at the reports that it [the booklet] has had great influence in the West in rousing silver sentiment.” These uneducated Westerners “must be easily misled,” while urban (presumably Eastern) sophisticates knew better.

When William McKinley took the Oval Office in the 1896 election, the free silver movement sputtered. The new secretary of the Treasury, Lyman J. Gage, acknowledged silver’s popularity, but therein lay madness: “Silver certificates, which form nearly one-fifth of the circulating medium of the United States, are dangerous. By their use a volume of inferior money has found an abnormal use.” In his 1937 memoir, Gage recalled how he publicly and “uncompromisingly advocated gold as our continued standard of payment.”

Gage believed the certificates specifically spurred counterfeiting. The New York Times openly pitied the bankers: “the whole series of silver certificates has proved unsuccessful from the point of view of those who handle money.” The detailed line-work dirtied, inviting counterfeiters to pass off poor replicas. One bank cashier complained to the New York Times: “The new certificates are an absolute nuisance when they get soiled from use,” leading to “constant and bothersome eye strain when one has to count the worn ones by the thousands daily.” The newspaper noted how Bureau engravers then revised the redesigns, stripping “History Instructing Youth” of shading and detail, thereby “exposing a great deal of white paper now covered by clouds and fancy work,” with the “one” numerals “converted into an unmistakable ‘one’ that could not [be] taken for a ‘five,’ and the expectations of counters of money were to be met as far as possible.”

That redesign never saw the light of day. “When everything was about ready for this new edition of the artist series of silver certificates,” the New York Times later reported, Gage preferred “to return to the old style of notes.” Affirming the status quo, the 1899 silver certificates boasted centered portraits, blank backgrounds, and large numbers. One observer approved “the simplest in design of any ever issued by the Government.” The nation has been following the same model ever since.

Modern anti-counterfeiting technology has made money safe, but the Tubman Twenty’s legitimacy rests in the fickle court of public opinion. The $20 bill will not dissolve tribalism. Cries of political correctness on the right and criticism from the left who reject the note as another commoditization of Black bodies create a chasm no single bill can bridge.

Nevertheless, what the new $20 bill can do is place the Black experience on par with past national leadership. This moment will require structural reforms in civil rights, political equality, and economic opportunities to fulfill the note’s potential. But as a symbol of democratic ideals that the dollar projects, the Tubman Twenty just might be worth its weight in gold.

Peter Y.W. Lee is an independent scholar in American history, focusing on popular culture and youth culture. He is the editor of Peanuts and American Culture and the author of From Dead End to Cold War Warriors: Constructing American Boyhood in Postwar Hollywood Films.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/09/d0/09d0cfa8-5a6a-421c-a9fe-c600de1b4242/picture1.png)