From the Editor: Curveballs at the Un-Magazine

From the first issue 40 years ago, Smithsonian has blazed its own path through the media landscape

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Edward-K-Thompson-631.jpg)

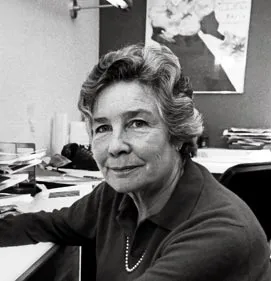

I don’t believe in ghosts, but I do believe the spirit of Ed Thompson, who died in 1996, still stalks these corridors, his hair slicked back, his tie loosened, a fat cigar stuck in his mouth. He swears a lot. He mumbles. Sometimes I feel him looking over my shoulder, shaking his head at what the world in general—and this magazine in particular—has come to. “What a lotta foofaw,” he might say, employing a favorite expression.

Edward K. Thompson had been the editor of Life, back when Life had clout, and after Life, in 1968, he signed on as an assistant to the secretary of state, a job that brought him to Washington. He then came to the attention of S. Dillon Ripley, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, who invited Thompson to his Connecticut farm.

Thompson recalled that day in his memoir, A Love Affair with Life & Smithsonian: “[Ripley] started off by observing that the Institution should have had a magazine since the early 1900s—well before our times. Since I was obviously there as a possible editor, I said I didn’t want to run a house organ. He said he didn’t want that either. After we had rambled over some possible subject matter, we agreed that the magazine’s content could be about whatever the Institution was interested in—or might be interested in. I threw in, ‘And should be?’ He agreed. That was about all that was articulated as a working idea, but an almost unlimited variety of subject matter was possible under such a concept.”

In early 1969, Thompson began putting together a staff. He hired Sally Maran, who had been a reporter at Life, as an assistant editor. The first issue, sent to 160,000 subscribers in April 1970, featured two elephants on the cover and the line “Courting elephants.” “We were very proud of it,” says Maran, who retired as managing editor in 2007. “We got 30 letters on the first issue. They were 25 yeas, 3 nays and 2 that you couldn’t tell.”

Institution reaction was more guarded. “We had curators calling and saying, ‘We have a great idea for a story on the Eastern Shore mollusk,’” Maran says. “I remember telling them, ‘Well, we are going to be a national magazine.’ And they said, ‘Well, we can cover Pacific Coast mollusks in another issue.’ We said, ‘Thank you very much.’ They were really upset that we weren’t a house organ.”

The director of the Natural History Museum wrote to Thompson asking that the magazine run a disclaimer disassociating its views from those of Institution scientists. Thompson hedged in his response. In a memo, the director fired back: “Many of our staff members have reacted negatively toward Smithsonian, largely as a result of your response to my memorandum.”

“I think we have got into an unnecessary foofaw about disclaimers,” Thompson replied and suggested the two have lunch. No disclaimer ever appeared in Thompson’s Smithsonian.

The magazine was catching on. “Each issue of Smithsonian is convincing evidence that eye-popping layouts, superb color photography and solid craftsmanship will always lure an audience,” Newsweek wrote in 1973, the year Smithsonian first turned a profit. By then, circulation had reached 465,000; it would hit a million two years later.

“Thompson’s brilliance was as a picture editor,” says Joseph Bonsignore, Smithsonian’s longtime publisher, now retired. “The pictures were played big as they could be. The best picture went on the cover. The second-best picture went in the centerfold. In each story, the best picture led the story.”

Coming up with great photographs was the job of Caroline Despard, who felt like Caroline Desperate. “I was always scared to death, because Ed Thompson was so demanding, and not always in a rational way,” she recalls. “He loved issuing impossible dictums. Once he asked me for a photograph of 100 babies all in one picture. I became very fond of him, but he was terrifying to work for.”

“There was a simple rule,” says Paul Trachtman, an editor from 1978 to 1991 and a contributor still. “Something had to be happening. There were places that editors thought were interesting and Thompson always said, ‘What’s happening?’ And if you couldn’t answer that question, you couldn’t assign the story.”

“He looked like a hog butcher, but he was one of the few geniuses I’ve ever been close to in my life,” says Timothy Foote, who had known Thompson at Life and joined Smithsonian for a 17-year stint as an editor in 1982. “It’s because of him that the whole thing worked.”

Edwards Park, an editor, wrote about his boss for the tenth anniversary issue: “[Thompson] smiles puckishly when pleased and glowers stormily when not. His office memos are collectors’ items. To one staff member after a dismal showing: ‘Your colleagues are aghast at your performance. You say it will improve. We await.’”

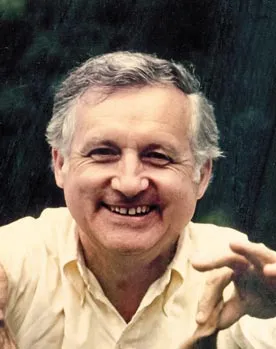

After ten years, Thompson handed the editorial reins to Don Moser, his deputy and a former Life colleague. Moser “pushed for higher-quality writing, better storytelling, writers who know how to ‘let the camera run,’” Jack Wiley, an editor under Moser, would later recall. “The aim always was to surprise the readers; present them with a story they had seen nowhere else and were unlikely to see in the future.”

“I brought in some new writers,” says Moser. “I pushed a little more to do some food-related stories and sports stories. But there was no big change, because [Thompson and I] both came from the same place and pretty much saw eye to eye on what ought to be in the magazine. I always felt that you have to give people what they expect. They expect history. They expect nature. They expect science. And then you’ve got to throw some curveballs at them.”

“Writers were always asking Don what he was looking for,” says Connie Bond, an editor for 19 years. “He would say to them: ‘That is your job to figure out.’ How could he tell you what he wanted when he wanted you to surprise him with something he hadn’t seen a hundred times before? He would say, ‘Get acquainted with the magazine yourself and then surprise me.’”

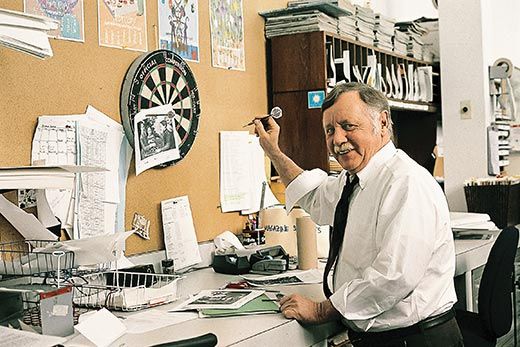

“We thought of ourselves as the un-magazine,” recalls Jim Doherty, also an editor for 19 years, beginning in 1983. “We prided ourselves on our singularity. We had a niche—and we were the only one in it. We refused to join the herd, chase celebrities, report trends, do what other magazines did. Our copy went on and on, often taking detours from the main narrative to explore esoteric and sometimes quite complex matters. And any subject was fair game, from square dancing to truck stops, from sports to music to education to ballet to art to science, you name it. We did not follow the pack. We followed our instincts—and our noses.”

Moser doubled Thompson’s decade-long tenure and took the circulation to two million, where it remains today.

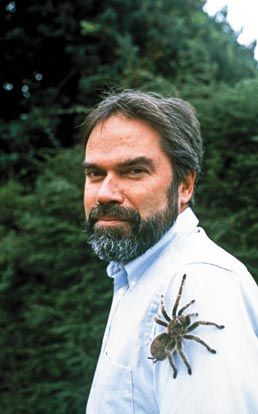

Richard Conniff has contributed to the magazine for 28 years, including this issue (see “Meet the Species,”). In 1997, three articles Conniff wrote about moths, giant squid and dragonflies won a National Magazine Award in the Special Interests category. “The thing that was great about the magazine, and still is,” says Conniff, “is that it has a breadth of interest and a curiosity about the world.” Some years ago he proposed a story to an editor at another magazine about a new event in Chicago—a poetry slam. To which, Conniff says, the editor replied: “‘The bleep in the street doesn’t give a bleep about a bleeping poetry slam.’ So I took the idea to Doherty at Smithsonian, who said, ‘Sure, go for it.’ The story we did helped turn the poetry slam into a national event.”

Conniff says Smithsonian’s basic premise remains unchanged: “I still think there’s the same editorial curiosity about the world, the same willingness to take on subjects that are quirky and revealing in small ways or large—that’s still what the magazine is all about.”

Reading Conniff’s words, I can’t help but smile and stand a little taller. Then I hear a mumbly voice in my ear: “What a lotta foofaw. Get back to work.” Right, Chief.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/carey-winfrey-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/carey-winfrey-240.jpg)