Frozen in Place: December 1861

President Lincoln addresses the State of the Union and grows impatient with General McClellan

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Civil-War-Sharpshooters-in-Mill-631.jpg)

”A disloyal portion of the American people have, during the whole year been engaged in an attempt to divide and destroy the Union,” Abraham Lincoln told Congress on December 3, 1861, in his first State of the Union message. After discussing the war’s effect on foreign commerce, Lincoln floated the idea that freed slaves might be encouraged to emigrate from the United States to territory to be acquired for them. Secretary of War Simon Cameron had recently advocated freeing and arming slaves, but Lincoln dismissed the proposal—for now. The president ended the speech, which would be telegraphed to newspapers for publication, by remarking on the eightfold growth in population since the country’s founding and saying, “The struggle of to-day is not altogether for to-day, it is for a vast future also.”

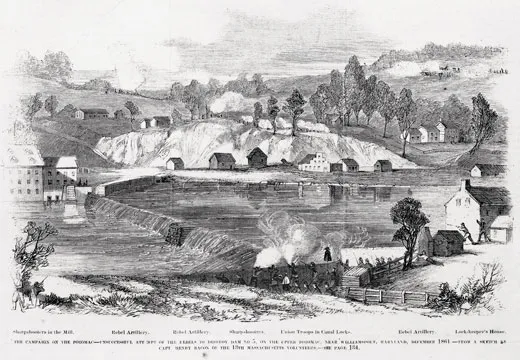

The month saw few battles, with no decisive advantage gained. A skirmish on Buffalo Mountain in western Virginia was typical. Union troops attacked a Confederate camp but withdrew after a morning’s fight—137 Union casualties, 146 Confederate. On the 17th, Confederate Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson launched an assault on Dam No. 5 on the Potomac River near Williamsport, Maryland, to stop the diversion of water into the C&O Canal, a critical Union waterway. “If this plan succeeds,” Jackson wrote a fellow general, “Washington will hardly get any further supply of coal during the war from Cumberland.” But Union fire fended off Jackson’s men with little damage done to the dam.

For the soldiers not seeing action, weather was foremost in mind. It’s “so intensely cold that we had to adopt some plan to keep from freezing,” a Union soldier in Missouri noted on the 10th. Another reported on the 20th from outside Annapolis, “freezing quite hard at night...anything but comfortable.”

Meanwhile, Lincoln was growing impatient with his freshly appointed top general, George B. McClellan. In a memo to the general about advancing the Army of the Potomac, Lincoln asked, “How long would it require to actually get in motion?” But no motion was forthcoming, and by month’s end McClellan had essentially called in sick, with typhoid fever. Despite Lincoln’s misgivings and the earnest advice of many people inside and outside his administration, he stood by the general.

On the last day of 1861, the president held a meeting with his Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Ohio senator Benjamin Wade was blunt: “Mr. President, you are murdering your country by inches in consequence of the inactivity of the military and the want of a distinct policy in regard to slavery.” That night, Attorney General Edward Bates wrote in his diary, “The Prest. is an excellent man, and in the main wise; but he lacks will and purpose, and I greatly fear he has not the power to command.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)