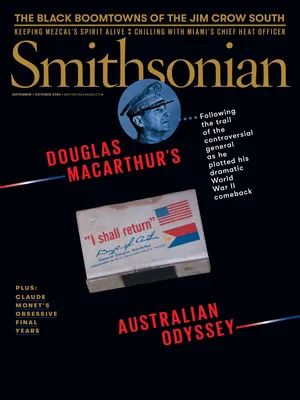

It’s a forgotten quirk of American military history that one of the most inspiring moments in the Pacific during World War II occurred on an abandoned railway platform in a dusty ghost town called Terowie, at the parched edge of the Australian outback. On March 20, 1942, on that unlikely, heat-baked spot, General Douglas MacArthur, the commander of the U.S. and Filipino forces in the Philippines, uttered his most famous and oft-quoted words, after a secret escape from the archipelago as the Bataan Peninsula was about to be overwhelmed by the Japanese: “I shall return.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/56/01/560188e4-1a8c-42c6-8453-80aa33fc3f9f/sepoct2024_k01_macarthur.jpg)

Today, reaching the site remains an odyssey. First, I flew to Adelaide, a sleepy city adorned with Victorian mansions on Australia’s southern coast, where I rented an SUV to drive 140 miles north into ever more haunting desolation. Trees became rare. The grass was scorched to a shimmering gold. Ancient, bald mountains hovered on the horizon. But the Australian hinterland is never truly empty: In one field, six emus watched me pass warily; in another, dozens of galahs, cockatoos with gray wings and pink crests, gathered on a ruined farmhouse and rose in a squawking cloud. The townships, however, grew more lonely. After passing the ominously named Worlds End, I called in at a one-room pub, where two sunburned farmers nursing beers helpfully offered directions: “You can’t miss Terowie, mate. There’s only one bloody road!”

This eerie landscape has hardly changed since the haggard 62-year-old MacArthur and his wife, Jean; 4-year-old son, Arthur; and Cantonese nanny, Ah Cheu, trundled by in a rickety train that March day in 1942, following a route called “the Ghan” after the Afghan camel handlers who plied it in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was the darkest moment of the Pacific conflict. Nine days earlier, the family had begun their escape from the Philippines in a white-knuckle journey by sea and air that became one of the iconic sagas of World War II—coming “out of the jaws of death,” as MacArthur described it at the time. Since the attack on Pearl Harbor three months earlier on December 7, 1941, Japanese forces had stormed across Southeast Asia, and MacArthur and 76,000 U.S. and Filipino troops were about to be encircled in the Bataan Peninsula when President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the general to evacuate to Australia, one of the last safe Allied bastions in the South Pacific.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/58/ae/58ae078e-0bed-4eca-8984-41ed3170cd04/sepoct2024_k07_macarthur.jpg)

On the night of March 11, the MacArthurs and 17 staff members secretly left in four PT boats from the island of Corregidor, then traveled under cover of darkness around 600 miles to an airfield in the southern Philippines, with most passengers, including the general, seasick much of the way. (He compared the voyage to “what it must be like to take a trip in a concrete mixer.”) Five nights later, the group squeezed into two overloaded B-17s and flew 1,500 miles farther south to Australia, an experience that was just as grueling. When they arrived, the tropical port of Darwin was being bombed by Japanese planes. They landed on an auxiliary airstrip, Batchelor Aerodrome; rushed onto two Australian National Airways DC-3s that were waiting with their engines running; and took off as Japanese fighter planes appeared on the horizon.

The flights were so harrowing that after landing in Alice Springs—an isolated trading post in the outback’s “Red Center”—Jean refused to go farther by air. A steam engine with three passenger carriages was made available, and on March 18, it began rattling another 900 miles south through the desert, averaging around 20 miles per hour and creating a rocking motion that allowed the general to nod off on his wife’s shoulder. It was the first time he had really slept since Pearl Harbor, Jean later recalled. Finally, at 2 p.m. on March 20, the train lurched to a halt at the junction of Terowie, where Aussie rail track gauges changed and passengers had to swap trains.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/27/77/27774e84-015d-4d75-a35c-97145549c5ec/sepoct2024_k06_macarthur.jpg)

Today, the outpost is even quieter than it must have been in 1942. The train depot was abandoned in the ’70s, and Terowie’s population slid from a high of around 2,000 in the late 1800s to about 135, leaving Main Street looking like a disused film set. I walked under corrugated iron awnings and peered through shop windows into rooms scattered with antique toys and clothes. A solitary general store, Murray’s, had a faded advertisement for Bushells Lan-Choo Tea on one of its walls and only a few food items on its shelves, like a Soviet grocery. The owner, Leanne Adams, was delighted to meet a visitor from the United States and pointed me to the station nearby, where I ambled across rusty tracks and onto the platform. Its sign now has only the town’s first letters, T-E-R, the others having fallen off. But the station did have a concrete plinth with a plaque recording MacArthur’s visit, including the improbable fact that he delivered here a “message that echoed around the world.”

MacArthur must have felt he had arrived on the moon when he stepped from his carriage here. But then he was surprised to find that, although his route down under was supposedly secret, a crowd of locals gathered behind a line of railway carriages to shout: “Welcome to Australia!” The general strode to a gap and saluted his admirers, as well as passengers in a nearby train, who all broke into cheers and cries of “goodbye and good luck!” Also waiting for MacArthur on the platform were some Aussie reporters from the Advertiser, an Adelaide newspaper. The PR-savvy general had intended to make a statement when he arrived at his final destination, Melbourne, but after confirming that his words would also be communicated by news wire agencies to the U.S., he gave an off-the-cuff speech about breaking through Japanese lines, and a promise to go back on the offensive from Australia: “I came through,” he thundered, “and I shall return.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/33/40/334051b2-5908-49b9-bcd0-57459c736efc/sepoct2024_k08_macarthur.jpg)

The next day, the Advertiser ran the interview on the front page with the headline: “I Came Through; I Shall Return.” It was not the lead story—it ran below the fold, beneath dire news about the advancement of Japanese forces in central New Guinea, an island some 80 nautical miles from Australia’s northeast tip. But the last three words struck a deep chord among the Allies, who were reeling from a string of catastrophic defeats, and they were republished from Washington to London and Moscow. Like an inspirational mantra, the phrase “I shall return” was repeated throughout the war, taking on “an almost magical aura,” as the historian Walter R. Borneman notes in his 2016 account MacArthur at War: World War II in the Pacific.

In private, MacArthur was far less assured. Having mismanaged the defense of the Philippines, he worried that his career was in tatters. Worse, when he arrived in Terowie that afternoon, he learned that he had been misled about the military situation in Australia, which was little short of disastrous. Brigadier General Richard J. Marshall, who had been a part of MacArthur’s escape entourage from the Philippines and had flown ahead, revealed that there were only a handful of American troops for him to command, most of them barely trained U.S. Army Air Forces personnel, with no infantry, tanks or heavy artillery. Most trained Aussie soldiers were in North Africa and the Middle East. The only combat aircraft were some 250 outdated planes, and there was no navy to speak of. There was little to stop an impending Japanese invasion.

Then the general was told that the 76,000 troops he had left behind in Bataan and Corregidor, in the Philippines, were beyond rescue. “MacArthur was dumbfounded,” Marshall recalled later. “The color drained from his face. His knees shook. His lips twitched. For a long time he was unable to speak. When he finally regained control of his body and his emotions, all he could do was whisper hoarsely, ‘God have mercy on us!’”

And yet two and a half years later, MacArthur fulfilled his promise at Terowie. On October 20, 1944, 80 years ago this fall, the general landed on the island of Leyte in the Philippines, where a photograph of him wading ashore became one of the war’s iconic images. Despite Americans’ ongoing fascination with World War II, it is lesser known how MacArthur turned the tide against the Japanese in that 31-month interim—running the war not from Honolulu or Los Angeles but from bases in Australia, where until April 1944 he had more Australian troops under his command than American.

“MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) is the least-known theater in all of World War II,” said James Zobel, the official historian at the MacArthur Memorial in Norfolk, Virginia. “If you look at compendiums on the conflict, Europe gets 500 pages, the Pacific War maybe 75, and the SWPA half of that. But look at what MacArthur and his forces did. The logistical challenges were amazing. They made landing after landing with just a few ships. In most of these islands, there were no docks, no roads—barely any towns. They had to build every single thing. It outstretches any other campaign.” For MacArthur personally, Zobel added, the long stay in Australia also saw his rise to fame—or notoriety—as one of the most colorful and controversial military leaders in U.S. history.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/48/fe/48fed228-2241-4ab1-ad85-77a653cf8be4/sepoct2024_k03_macarthur.jpg)

Having grown up in Sydney, I have an odd personal connection. My grandfather served under MacArthur’s command as an aerial surveyor in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) and worked with the U.S. Army Air Forces assessing the status of captured airstrips as the Allies fought in New Guinea, then island-hopped north. I knew very little about the story of Flying Officer Noel Perrottet until I recently reopened a cache of letters sent to my father from the front, usually simply giving the return address “Pacific.” It was in part to understand what my grandfather lived through—and the background to his death—that I traveled from my home in downtown Manhattan to Terowie and beyond, to explore the relics of the little-known wartime interlude when today’s robust U.S.-Australian friendship was cemented.

On March 21, 1942, the day after his Terowie speech, MacArthur’s safe arrival in Melbourne became one of the most powerful morale boosts—and propaganda triumphs—of the war. The Allies were in desperate need of a hero, and Roosevelt promptly awarded the general the Medal of Honor despite the fact that he had presided over one of the worst defeats in U.S. military history. By April, the American and Filipino troops he had commanded in the Philippines were starved and bombed into surrender, then sent on the so-called Bataan Death March to gruesome Japanese-controlled POW camps, killing as many as 500 American and 2,500 Filipino soldiers along the way. Instead of castigating MacArthur, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, in his role as War Plans chief, supported his promotion to supreme commander of the Southwest Pacific Area, which stretched from Australia to the Philippines and the South China Sea—an area nearly twice the size of Europe. MacArthur, who had begun the war as a relatively minor figure, became America’s most popular general, appearing on the cover of Time magazine and receiving a barrage of adulatory press. “It was the role of a lifetime and, publicly, he played it brilliantly,” writes Borneman.

For the beleaguered Aussies, MacArthur was nothing less than a savior. When he arrived in Melbourne in his crumpled khaki bush jacket and battered field marshal’s cap, the general was greeted by cheering crowds and given a motorcade with a guard of honor. A wave of relief spread through the country: “The United States would not send its greatest contemporary soldier to a secondary war zone,” Melbourne’s Herald proclaimed, proving that the U.S. “regards Australia as a sphere of extreme importance.” Zobel, of the MacArthur Memorial, said, “For the Australians, it was everything. The entire continent was wide open! Then MacArthur turned up. It was a sign that the Americans had their backs.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b6/97/b697babe-a3d8-4aa4-99f9-e083863b5324/sepoct2024_k02_macarthur.jpg)

There was no formal alliance between the United States and Australia, so the next stop on MacArthur’s grand tour was the capital, Canberra, to meet with the prime minister, John Curtin. They were an odd couple: MacArthur was a deeply conservative patrician and professional soldier, Curtin a former socialist trade union organizer who had been imprisoned for being an anti-draft campaigner in World War I. They were also charting new diplomatic territory. Since its foundation, Australia had been blindly loyal to Britain, and in 1939 it immediately prepared troops to fight the Germans, Italians and Vichy French in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. But soon after Pearl Harbor Curtin summoned the country’s troops back home to stave off the Japanese on the doorstep, infuriating Winston Churchill. Curtin made it clear in a famous radio address that Australia’s first priority was its own defense rather than Britain’s, and it would now throw its lot in with its new ally, the United States, against the common enemy in the Pacific.

MacArthur’s first task was to protect Australia from what seemed like imminent invasion. It was a daunting challenge: The country was as vast as the contiguous U.S. but with only seven million inhabitants, most in the southeast. (By comparison, the U.S. in 1942 had 134 million.) In the north, Darwin was facing near-weekly bombing raids from Japanese bases on Timor and surrounding islands, and thousands of miles of tropical coastline were uninhabited and undefended. Some intelligence reports suggested that three Japanese divisions were about to land, and among Aussie civilians, hysteria ruled. In May, Japanese two-man “midget submarines” entered Sydney Harbor and tried to torpedo the cruisers USS Chicago and HMAS Canberra. They missed and sank instead a ferry that had been converted for war service, killing 21 sailors.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1c/a6/1ca6ffff-72dc-4b14-85f7-7dbe1c6c7a7d/sepoct2024_k14_macarthur.jpg)

The Allies did not realize that Australia’s vast scale was working to its advantage. Rather than risk a costly invasion, the Imperial Japanese Navy had planned to cut the country’s supply lines to Hawaii and the U.S. West Coast, blocking its use as a base and strangling it into submission. But the Allied naval victories of the Coral Sea in May 1942 and Midway in June headed off that grim possibility, and MacArthur’s attention turned to stopping the Japanese land advance in Papua New Guinea.

To be closer to operations, MacArthur decided to move his office 850 miles northeast to Brisbane, a subtropical river port resembling an Aussie New Orleans. The capital of the state of Queensland, it was at the time a drowsy backwater: It boasted only one high-rise, the nearly 300-foot-high City Hall clock tower, said to be modeled on St. Mark’s Campanile in Venice. “You’d expect to see Wyatt Earp riding down the street,” one nonagenarian Brisbanite told me of the time.

On July 23, the general and his family arrived by train to another hero’s welcome and settled into Lennons Hotel, Brisbane’s most luxurious lodging, joined by most of the officers who had escaped with him from the Philippines, dubbed the “Bataan Gang.” For his headquarters, staff had commandeered the eighth floor of a nearby insurance company office, known as the AMP (Australian Mutual Provident Society) Building. Constructed of relatively bomb-resistant granite and sandstone with a concrete-reinforced roof in English Renaissance style with classical columns and marble statues, it also offered such rare (for Brisbane) modern conveniences as three elevators.

For the next two and a quarter years, apart from brief forays to the major township in Papua New Guinea, Port Moresby, to raise troop morale, MacArthur ran the Southwest Pacific war effort from its chambers. He remained a showman the entire time: Every morning, he was chauffeured the two blocks from Lennons to the AMP Building in a flashy Wolseley limousine with four stars on the bumper and the plate U.S.A.-1, attracting crowds of admirers along the route.

Today, it’s not hard to spot the AMP Building in central Brisbane: It looks as out of place as a medieval watchtower among the city’s mix of sleek glass skyscrapers and exuberant subtropical gardens flitting with native birds. Brisbane was once the butt of jokes in Australia for knocking down its heritage in favor of glitzy developments, helping to earn it the tongue-in-cheek nickname “BrisVegas,” but it has over recent decades begun to protect its surviving historical structures. In 2004, MacArthur’s offices were restored as a museum; in early 2024, it reopened after a major $63 million renovation.

The relaxed institution offers some intimate connections to the general. “Fancy a photo sitting in MacArthur’s chair?” an attendant asked me when I visited, lifting the rope from a stanchion protecting a leather-bound throne in the former company boardroom that became his private office. After a moment’s hesitation—what would MacArthur think?—I eased behind the wooden desk and tried to channel the general, whose larger-than-life personality was once on full display in this office. A U.S. Army Air Forces lieutenant general named George H. Brett called him a “brilliant, temperamental egoist … who can be as charming as anyone who ever lived, or harshly indifferent to the needs and desires of those around.” Brett lamented that everything about MacArthur was on a “grand scale,” his “virtues and triumphs and shortcomings.” It’s a verdict that most biographers have agreed with since: “William Manchester summed him up in American Caesar,” said John Wright, the Brisbane museum’s managing director. “He was ‘a great thundering paradox of a man,’ with aspects of greatness mixed with incredible pettiness. His overwhelming driving force was his ego. That was why he was so controversial.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/03/06/03065d62-d78f-4846-85a5-535be5355d98/sepoct2024_k10_macarthur.jpg)

Along with the chair, the museum has such odd relics as MacArthur’s cigar box and a portrait of George Washington, which the general chose instead of Roosevelt because, he reportedly said, “I’m not having any Democrat looking down on me.” The museum also preserves the original conference table where the Bataan Gang and top Australian officers held daily meetings at noon around a giant map of the Pacific, across which they pushed miniature airplanes and ships like a chess game.

As other museum exhibits revealed, when MacArthur first set up office here in late July 1942, the strategic situation looked desperate. The Japanese had made new amphibious landings in New Guinea and were pushing toward Port Moresby. While the battles in Guadalcanal and Iwo Jima are more famous, MacArthur’s campaign in New Guinea was essential for success in the Pacific War. The most urgent challenge for his mostly Aussie and some Papuan troops was to halt the Japanese advance along the treacherous Kokoda Trail, a 60-mile footpath that ran across the island’s jungle-covered mountainous spine, only two to three feet wide and reaching more than 7,000 feet high at one point. Vicious fighting occurred in gruesome conditions, with soldiers suffering from malaria, dengue fever, dysentery and tropical ulcers in a rain-sodden labyrinth so dense that those who left the trail were often never seen again.

“The early days were a time of terror for everyone,” said Zobel. “MacArthur had to create an infrastructure out of nothing to get troops to New Guinea and to supply them.” Still, the Japanese suffered their first defeat on land in September while trying to take Milne Bay, and they were halted on the Kokoda Trail. The news lifted spirits across the Pacific and shattered the myth of Japanese invincibility.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ff/06/ff06cbf9-8c9e-47aa-bcc0-4b689fde768a/sepoct2024_k12_macarthur.jpg)

To me, the most intriguing exhibits at the museum recounted U.S.-Australian relations in wartime Brisbane. Cheerful propaganda photos showed Hollywood stars like Gary Cooper on morale-boosting visits and smiling American soldiers teaching Aussie girls the jitterbug. Displayed in one glass case was the wedding dress of one of the many “war brides” who returned to the States with G.I.’s. But others recounted more tense interactions as the tiny city became the key American base in the South Pacific. More than 4,000 American troops had arrived in December 1941, only three weeks after Pearl Harbor, in a convoy diverted from the Philippines. Over the next four years, an estimated one million American troops would pass through Brisbane, turning the outpost of fewer than 350,000 inhabitants upside-down.

The U.S. influx was a cultural shock on both sides: G.I.’s were given handbooks to explain exotic Aussie manners, while many Brisbanites only knew about “Yanks” from cinema. The result was friction on the home front: While the Japanese invasion of Australia had been averted, there was a “Battle of Brisbane”—a fierce, two-day street fight that broke out between Australian and U.S. troops on Thanksgiving night, 1942.

The saga is part of local folklore, and the city’s historical institution, Museum of Brisbane, even offers a walking tour of “battle sites.” When I signed up, my guide Brian Ogden took me first to the stately Federation-style building that was the flashpoint of the violence. Now a 7-Eleven, it once housed the American PX (Post Exchange), where U.S. soldiers could buy luxury goods like cigarettes, liquor and chocolates, which were either prohibitively expensive or unavailable to the rest of the city under wartime rationing. This made them popular with Brisbane women, to the chagrin of Aussie “diggers,” as soldiers were called, who also resented the Americans’ polished manners and snappy uniforms. “The Aussie blokes were a rough bunch by comparison,” Ogden said. “They weren’t into the niceties of life.”

Ironically, the spark for the riot came from an act of friendship. At dusk on November 26, an Aussie soldier invited an American serviceman to join him for a beer at a canteen near the PX. When the U.S. serviceman, who was somewhat the worse for wear, accidentally bumped into another Aussie soldier with some friends and an altercation seemed likely, they attracted the attention of two Military Policemen, who were disliked by both Aussie and American soldiers for their arrogant behavior. When the MPs demanded the American soldier’s leave pass and threatened them all with batons, angry words led to blows. The MPs were forced to barricade themselves inside the PX as at least 500 Aussie soldiers soon besieged the building, throwing bricks, using uprooted street signs as battering rams and shouting, “Come out and fight, you bastards!” Matters took a drastic turn when U.S. reinforcements arrived, including an MP carrying a shotgun. In the ensuing scuffle, Aussie private Edward Webster was shot in the chest, killing him. A wild fistfight followed, which a journalist watching from a hotel balcony described as “the most furious battle I ever saw during the war.”

The next night, brawls across Brisbane sent at least 20 soldiers into hospitals. At one stage, a High Noon-style shootout was narrowly averted by an officer. When order was restored, reports of the violence were censored to keep up morale, and MacArthur made no recorded comment. The tensions soon evaporated, and it was recalled with bemusement by both sides, like a rowdy rugby match. G.I.’s found Aussies cheerfully slapping them on the back in pubs, chortling, “Oh, wasn’t that a good ruckus we had the other night? And have a beer on me.”

In January 1943, as American and Aussie troops in New Guinea began to beat back the Japanese advance, MacArthur announced the recapture of the strategic base of Buna. The victories began to pile up over the year as MacArthur put into motion a new strategy of island-hopping around New Guinea and north into the Pacific, bypassing strongly defended outposts and isolating them until they surrendered. “The Imperial Japanese Navy didn’t know how to deal with MacArthur,” Zobel said. “He had no navy to speak of, but his troops just popped up everywhere, often with 600-mile advances at a time. ‘How do we fight him?’ And codebreakers had cracked the Japanese codes, so he knew where they were.”

Back in mid-1942, MacArthur had ordered Allied intelligence agents in Brisbane to set up a unit called Central Bureau in a fine Victorian mansion, Nyrambla, filling one of its garages with IBM tabulators, the forerunners of computers. The result of one code-breaking triumph is on display in a glass case in the MacArthur Museum in Brisbane today: the control yoke from the downed airplane of Japanese Marshal Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the mastermind of Pearl Harbor. Thanks to an intercepted message relaying his itinerary, Yamamoto was shot down and killed in April 1943 by U.S. fighter planes en route to Bougainville Island. “As far as the United States was concerned, Yamamoto was public enemy number one,” Wright, the museum’s managing director, said. Later, in 1944, Australian troops discovered an entire Imperial Japanese Army cryptography library buried in a steel trunk at the bottom of a riverbed by retreating signalers. The volumes were taken back to Brisbane, where they were dried out and decoded, allowing MacArthur to plan amphibious landings with full knowledge of Japanese location and plans—a vital advantage.

Nyrambla still stands as a private residence, and other offbeat sites related to MacArthur’s presence survive all over Brisbane. While Lennons Hotel has vanished, I checked into the Inchcolm by Ovolo, a hotel in the renovated neo-Georgian building where the general would visit his personal physician. All these years later, it has retained its ’20s look, with polished wood paneling, vintage furniture and the original cage elevator. Other sites are even quirkier. In 2008, a workman restoring City Hall uncovered the “Signature Wall” in the basement, covered with over 150 graffiti scrawled by soldiers before shipping out to fight under MacArthur’s command. Many were as indecipherable as hieroglyphics, but I made out the names of Gnr. (gunner) Wallace H and Charlie Sankey—and wondered if my grandfather had written his name there before flying north with the RAAF in 1944.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/34/7d/347dd4de-c99e-40fa-9b2b-f815e5cc1bfe/sepoct2024_k09_macarthur.jpg)

Hidden by the entrance to the Howard Smith Wharves on the Brisbane River are a few concrete bomb shelters overgrown with moss. From there, a walking trail runs to the site of the Capricorn Wharf, a dry dock where some 800 American servicemen worked. The former heightened-security site is now open to the public, with plaques commemorating the 50 or so subs that once berthed here for repairs, making it as busy as Pearl Harbor. Disused hangars downtown have been turned into a cocktail lounge called the Stratton Bar & Kitchen, and a music venue, the Triffid. But perhaps the most intriguing aviation relic was a mysterious site called Hangar No. 7 where Wright told me that “secret research” had been conducted on Eagle Farm airfield in a far-flung northeastern suburb.

On my last afternoon, a taxi dropped me at a café by a busy highway, where I asked a truck driver for directions. He turned out to be a history fan. “Oh, mate,” he enthused. “Hangar No. 7 is Brisbane’s answer to Area 51. And nobody knows about it!” He pointed me to a ramshackle structure protected by a barbed-wire fence. Outside, a plaque explained that a classified military program had begun here in April 1943, when MacArthur authorized the Allied Technical Air Intelligence Unit to reassemble pieces of Japanese Zero fighter planes that had been shot down. The Zero had proved more maneuverable than Allied planes, so engineers built a Frankenstein-like replica and sent it on mock dogfights over Brisbane, to reveal the Zero’s strengths and weaknesses, including how to outmaneuver it by maintaining higher speed and altitude.

On my way back downtown, I spotted the turrets of a Renaissance Revival building rising by a eucalyptus-fringed creek, with a neon sign for XXXX beer. It turned out to be the beloved Breakfast Creek Hotel pub, built in 1889 and a favorite Brisbanite watering hole for servicemen in World War II. I pulled up a stool at the bar, whose tile-covered interior remains unchanged since the MacArthur years, and noticed a faded photograph of Australian and U.S. soldiers happily drinking together as a female publican drains a wooden beer keg. It seemed an appropriate memorial to the warming U.S.-Aussie relations in the war.

The Allied troops fighting together developed a fierce camaraderie, while the elite First Marine Division from Guadalcanal, who arrived in Melbourne in early 1943, felt so welcome that they adopted “Waltzing Matilda,” the most beloved Aussie folk ballad from the 19th century, as their divisional song. By contrast, there were increasing U.S.-Australian tensions at MacArthur’s war office in Brisbane. Top Aussie commanders like General Thomas Blamey, who had to deal with the general’s abrasive command style personally, felt they were treated as second-class allies and ignored in decision-making. They also seethed that MacArthur’s self-aggrandizing press releases often left out that Aussie troops were on the front lines.

“The situation got so bad,” Wright told me, “that the Australian press started asking, ‘Where is the Australian army? Because we never hear about them.’”

The Aussie sense of being written out of the war soon became a reality. By mid-1944, the U.S.-Australian joint forces had seized bases in the islands of northern New Guinea within striking distance of the Philippines, the strategic goal closest to MacArthur’s heart. With full war footing back home, American troop numbers and resources now far outstripped those of the Aussies, and the general began sidelining his former allies to fulfill what he felt was his destiny. Although he had relied on Australian troops for his victories, MacArthur wanted the liberation of the Philippines to be a purely U.S. operation, reneging on what Prime Minister Curtin had taken as promises and relegating the Aussies to completing the job in New Guinea and, later, an invasion of Borneo. “The Australians resented being left out,” said Zobel. “They wanted a core of their troops in the Philippines assault. But the truth is, MacArthur now had so many American troops that he could not supply the Aussies.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2b/1d/2b1dfb3a-cff7-40f3-bac1-534d9655fb6d/sepoct2024_k16_macarthur.jpg)

In September 1944, the general prepared to leave Brisbane. Curtin was dying of heart disease, so MacArthur flew to Canberra to bid adieu. Although their relationship had become increasingly tense, Borneman wrote in his biography, “together they had nonetheless turned Australia from tempting target into offensive bastion, and their parting had a touch of melancholy for both men.”

The general also had a few days of R & R in Brisbane, taking long afternoon drives with his wife and son. Then, in mid-October, he flew north and boarded a cruiser to oversee the amphibious landings on Leyte, which he called A-Day since D-Day was associated with Normandy. On October 20, MacArthur made a radio address from the beachhead that was broadcast around the world, declaring in an emotional voice: “People of the Philippines, I have returned.”

The reality was less straightforward. Securing the strategic central island proved far more grueling than expected, with bitter hand-to-hand fighting on land accompanied by the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the largest naval conflict in the Pacific War, a resounding U.S. victory despite the havoc of the first kamikaze attacks. On January 9, 1945, a landing was made on the island of Luzon for the push to Manila. But instead of evacuating, the Japanese defended the beautiful colonial city block by block: Some 100,000 Filipino civilians were killed, leaving it an “unrecognizable ruin of rubble and rotting corpses,” Borneman writes. Only on February 23, 1945, could MacArthur visit his old residence, the Manila Hotel.

A little over six months later, on September 2, 1945, MacArthur led the ceremonies accepting the Japanese surrender on the deck of the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

When it came to Australia, MacArthur knew he would not return. But his time there had set the stage for him to become an international hero. As Borneman put it, MacArthur had “become one of the best-known generals in not only American history but also world history.”

The Pacific War was a hard-won victory, and one of the casualties was my grandfather Noel Perrottet. I had never known the details, but researching MacArthur’s story prompted me to look up Noel’s service records in the National Archives of Australia and follow his postings through the SWPA campaign.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ce/e0/cee016fd-b709-4a1f-8a9b-38b875647293/sepoct2024_k13_macarthur.jpg)

Serving as a flying officer in the RAAF, he worked with the U.S. Army Air Forces in wild corners of New Guinea whose names mainly only specialist historians recognize today—Tadji, Nadzab, Noemfoor, Biak—and Morotai Island in the Moluccas, now part of northeastern Indonesia. He crossed paths with MacArthur on June 10, 1945, when the general and other top brass inspected a beachhead on Labuan in Borneo, which had been seized by amphibious landings that morning. MacArthur congratulated the commanders on a “flawless” operation: “Please accept for yourself and convey to your officers and men the pride and gratification I feel in such a splendid performance.”

But although these islands often had the golden sands, palm trees and crystalline waters of a travel brochure, they were riddled with disease. Noel returned to Sydney in August 1945 covered in mysterious ulcers and suffering from an insidious sickness that affected his lungs and digestion. He tracked its progress with precise notes in a brown-leather diary (“Breathing difficult again” … “Very fatigued” … “Fit dry retching about 6, 11, 5 p.m.”), but doctors were baffled. On November 26, 1946, he died in the military hospital in Sydney at age 38, leaving his wife and four children under the age of 10.

On March 22, 2023, the outback ghost town of Terowie had a renewed burst of life when crowds converged for an international ceremony celebrating the 81st anniversary of MacArthur’s visit. (Plans to celebrate the 80th were derailed by the Covid-19 pandemic.) Some 250 people gathered for speeches on the train platform, including Aussie war veterans like 102-year-old Keith “Chook” Fowler. The U.S. defense attaché to Australia, Colonel Shane Gries, declared that it was a thrill to give an address on the spot where MacArthur spoke his famous words: “The speech that General MacArthur gave … was a tremendous moment in American military history and world history.” The current editor of Adelaide’s Advertiser, Gemma Jones, gave a few words on the media’s role in bringing “one of the most stirring speeches in history” to the world’s attention from this remote outpost. Arthur MacArthur, who had been 4 years old on that day in 1942 and is now 86, sent a statement of appreciation from his home in New York, where, in contrast to his father, he has avoided the public eye.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1c/d9/1cd9ad76-32c3-4537-b3c7-dbcd8c06f63e/sepoct2024_k04_macarthur.jpg)

“Old soldiers never die,” Douglas MacArthur said in the concluding remarks from his last speech to Congress on his retirement in 1951, quoting an old barracks ballad. “They just fade away.” By then, his reputation had been tarnished by his controversial command of the United Nations forces in the Korean War, which had led to his discharge some nine days earlier by President Harry S. Truman for insubordination. He continues to polarize Americans today, as revisionist historians have chipped away at his heroic World War II image, arguing that his overweening ego led him to order costly campaigns that were strategically unnecessary; even the bloody invasion of the Philippines, critics argue, may have been a distraction from the push to Japan.

Today, the general’s legacy in Australia remains contradictory, even in his shrine at the MacArthur Museum Brisbane. “MacArthur is portrayed by some as the forerunner of the current Australian-American alliance,” said Wright. “In reality, he did little to foster the coalition and much to discourage it.” Once he had left Australia, MacArthur largely forgot it. “On the other hand, the farther you got from the general’s H.Q., the better the relations between the Allied forces were. Many long-lasting friendships were formed by Australians and Americans, some of which involved people who became very influential citizens of their own country.” The result in 1951 was the ANZUS Treaty guaranteeing military cooperation, which has been strengthened many times since, and cultural exchanges between Australia and the U.S. in almost every field.

And it all began on a dusty train platform in the outback.

:focal(900x600:901x601)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c9/10/c91015d0-3bc8-4372-b958-41f4b8b4ee01/sepoct2024_k05_macarthur.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/12/f1/12f15365-86c0-42e8-91f2-61f7aaab0d82/sepoct2024_k17_macarthur.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d9/cd/d9cd5447-a476-4155-adbd-5d328a396047/sepoct2024_k11_macarthur.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1b/54/1b5427ab-3526-456c-8c0c-7024b9a60f87/sepoct2024_k18_macarthur.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)