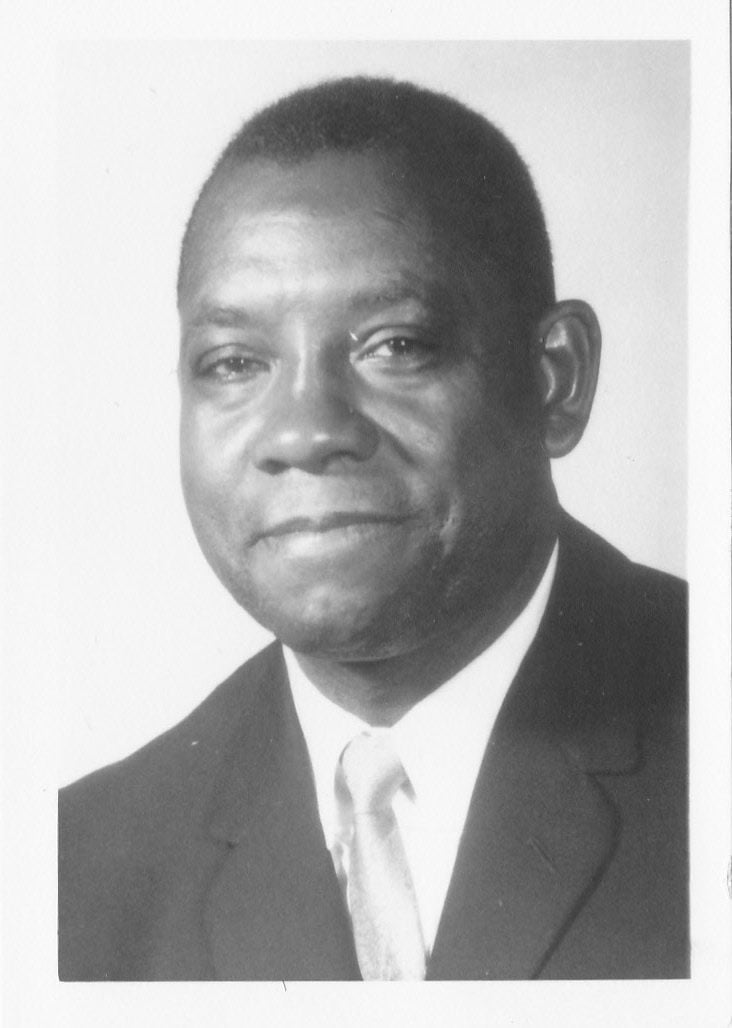

George Washington Gibbs Jr. Defied Danger and Racism to Become the First African-American to Visit Antarctica

“He had bigger visions and would not be contained in a box,” his daughter says

:focal(415x240:416x241)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b2/28/b2281dd3-971c-47e7-a9c6-d64fc8b5db07/george-washington-gibbs-jr.jpg)

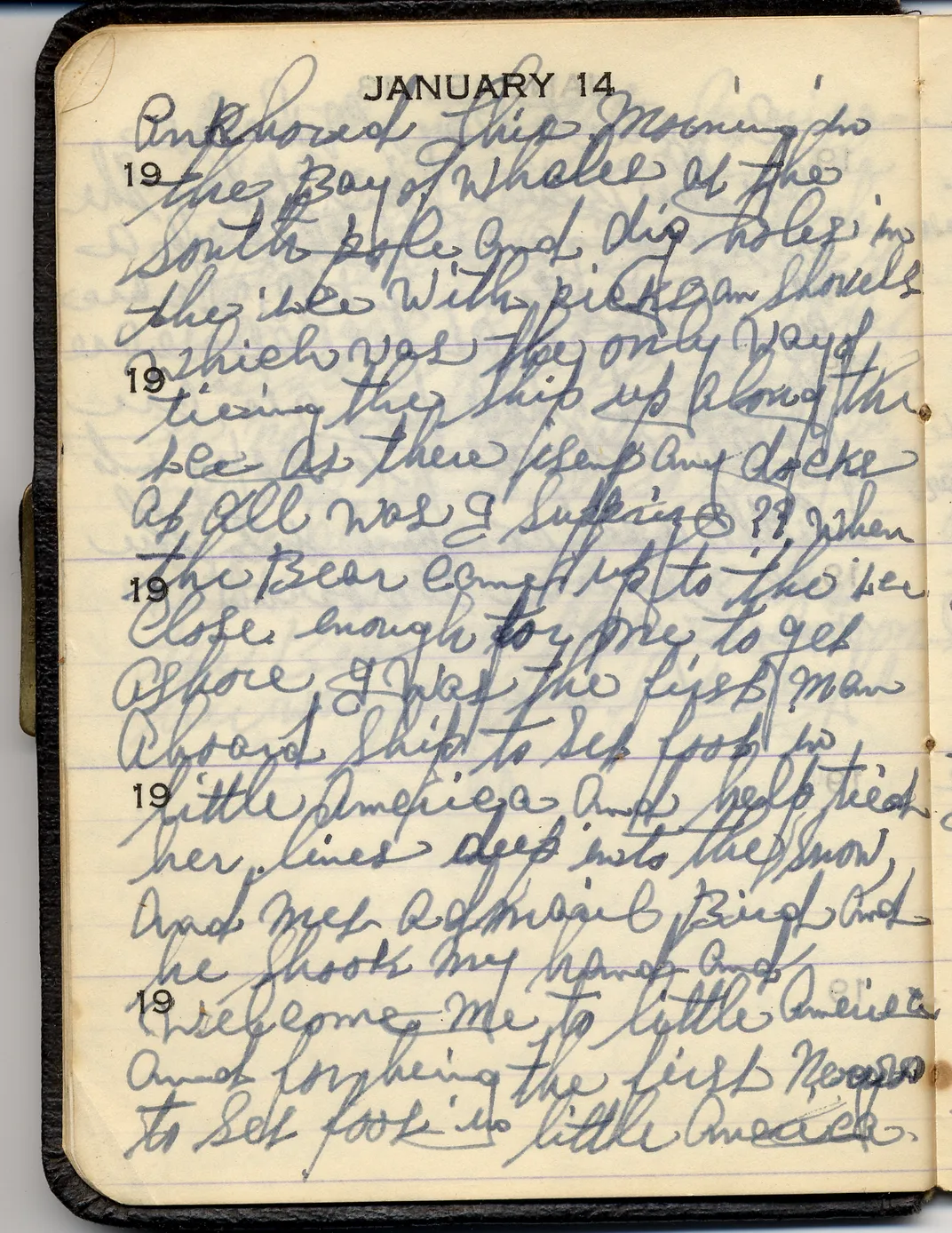

Day after day, the ship rocked back and forth like a “wild horse” that couldn’t be tamed, causing a crew filled with experienced sailors to lose their stomachs. The rough southbound sailing was compounded by frigid winds and temperatures well below zero. It was aboard this pitching vessel—the USS Bear—that a young, winsome mess attendant named George Washington Gibbs Jr. put in long days to provide meals for the crew (when they could keep them down) and fought to launder and clean despite a dearth of fresh or warm water. Gibbs, selected from many eager candidates to join famed explorer Admiral Richard Byrd’s third expedition to Antarctica, would achieve a historic first when they arrived on the Ross Ice Shelf on January 14, 1940, becoming the first African-American to set foot on the frozen continent.

Gibbs joined an expedition fueled by high expectations—chief among them those of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who believed in expanding research facilities for the United States and allotted funding accordingly. It was also during a time of intense international competition—Antarctic exploration had expanded significantly in the decades before, and was about more than strict scientific and geographic knowledge. “There’s a huge national prestige factor going there,” says polar and maritime historian Glenn Stein. The La Crosse Tribune noted at the time as the USS Bear set sail that “Uncle Sam is paying the bill and expects a return in terms of stronger claims to the frozen lands.”

In light of such investment, it was incumbent on Byrd to select only the most qualified to be take any part in the mission. “It was considered a particular honor to be able to go,” says Stein. At that time “very, very few people, few human beings would ever be able to be in a place like Antarctica.”

When Admiral Byrd shook Gibbs’ hand and congratulated him for those first steps, he was acknowledging a milestone reached despite added barriers. He had joined the expedition as a mess attendant because at the time it was the only position in the Navy that was open to African-Americans —a source of frustration for the 23-year old seaman.

“Was up at five-thirty this morning, as usual, to begin my daily routine as a mess attendant, which is monotonous,” he wrote in his diary on February 2, 1940. “I am doing the same thing every day and at times I think I will go nuts, especially when I think about my race being limited to one branch of services, regardless of the many qualifications that members of my race have… However…with the little courage and faith I have left and live by… after these four years are up, I will try something that will offer me a better opportunity in accomplishing something in life, rather than just occupying space.”

Gibbs would go on to do much more than occupy space, aided by a personality that encompassed both a good-humored, outgoing nature drawing others in and a quiet determination to push through obstacles. Gibbs left the racism he faced in Jacksonville, Florida, and worked his way to a recruiting station in Georgia. His father encouraged him to leave Jacksonville “as quickly as possible, because he knew he that he had bigger visions and would not be contained in a box,” says his daughter Leilani Henry, who has traveled to Antarctica to research her father’s journey and is currently writing a book about the icy continent. Gibbs’ parents divorced when he was young, but he remained close to both as he served at multiple stations around the country and overseas. Gibbs married Joyce Powell, whom he met in the Navy community of Portsmouth, in 1953.

During his months on expedition, Gibbs handled both the endlessly mundane and acutely dangerous with equanimity. A few days after they arrived in Antarctica, he was sent to collect penguins for scientific study. Gibbs and his companions—who lacked radio communications equipment—lost sight of the ship as the intense Antarctic fog rolled in, finding their floating home only when the foghorn sounded and guided them back. At one point during his limited free time, Gibbs went for a walk on the ice solo—only to fall into an unseen crevasse, which happened to be narrow enough to allow him to pull himself up by the arms. Both in crises and ordinary challenges, “he always had the attitude that things were going to turn out all right,” recalls his son Tony Gibbs.

Gibbs’ diary, which recounts those perils, went unread for decades. Believing it was lost, Joyce Gibbs found it after her husband died. She says she scanned it briefly before mailing it to her daughter, who says he did not keep a habit of writing in a diary at any other time in his life. “I think that going to Antarctica was a momentous event, a very special event and he knew that it was special so he wanted to record that,” says Henry.

Though he endured racism aboard the ship, he allowed only brief acknowledgement in his diary to men “who at times make this cruise very hard for me” and would have had him removed—if they could. Gibbs earned the respect of the leadership, who issued him two citations during his time aboard the Bear, the first for his preparations to ready the old, once-retired vessel for its journey, and a second at its conclusion, for “outstanding zeal and energy and for unusual spirit of loyalty and cooperation which he invariably displayed under trying conditions.” These words carried more weight than those who would have seen him removed.

Soon after Byrd completed this expedition, interest exploring frozen frontiers would soon be eclipsed by America’s entry into World War II. It was the South Pacific, not the South Pole, that absorbed the efforts of men like Gibbs, who was soon enmeshed in pitched maritime battles, serving aboard the USS Atlanta during the Battle of Midway Island in June of 1942. In November of that year, the Atlanta would be torpedoed by Japanese ships, engulfing the cruiser in flames. In the nighttime chaos the cruiser was then inadvertently shelled by a friendly ship; all told an estimated one-third of its crew were killed.

Regardless of assigned duties, “everybody had to fight, everybody had a battle station,” says Tony Gibbs. As the ship burned, Gibbs was responsible for handing out life jackets to survivors – until there was not one left for himself, Henry says, but confident in his own physical fitness, Gibbs survived the night and the day that followed amidst the perils of the ocean, which held both enemy ships and sharks.

But rescue did not mean reprieve – in short order Gibbs would end up on land fighting in foxholes, hastily repurposed with little training for ground combat to fight with the First Marine Division. With no chance of taking leave or going home, he endured prolonged hardship in those foxholes, then as part of a torpedo boat squadron, and fought in battles for the Pacific islands of Tulagi, Bougainville and New Georgia. He was sickened by malaria, which caused lingering health issues later in his life.

“Whatever the adversary, whether it be in the hardships of the South Pole or the fury of the enemy’s guns, Gibbs has not only survived but come out a head higher than the average person,” Lieutenant Robert Satter later wrote in a letter about Gibbs. “With such sterling qualities of character, as in war so in peace he cannot help but be outstanding in everything he does.”

When his days of combat and navigating frozen seas were behind him, Gibbs would go on to fight in battles of a different sort as a civilian. Among many examples, Henry recalls Gibbs and a close friend sitting in restaurants, trying to get served in the 1950s. “I think the idea that this is not fair and somebody has to do something about it – that generation, the only thing that was important was making sure these things weren’t every day in people’s lives forever and ever,” says Henry. “They were going to change that.”

After retiring from the Navy in 1959 as a chief petty officer – and with numerous medals of merit - Gibbs enrolled in college and earned a degree from the University of Minnesota. Gibbs spent the next three decades working in personnel for IBM (Gibbs walked to work every day virtually every day, shrugging off the Minnesota cold by contrasting it with Antarctica) and later establishing his own employment placement company. Gibbs gained was heavily involved in the community, serving as a leader in numerous community organizations.

But being well-known as a civic leader did not make him immune from discrimination—he made headlines when the local Elks Club denied him membership, a move he fought. As a result of the controversy, their liquor license was soon revoked.

“You got to be a fighter all the time, every step of the way,” Gibbs told the Minneapolis Star in 1974 during the controversy. “I don’t mean you go around punching people, you just keep doing your job well, get a good record going, never give anybody a chance to rake you over the coals. I guess that’s one of my basic philosophies. If you do a good job, you’re just as good as the next guy.”

Longtime friend George Thompson, a retired engineer, recalls Gibbs as a “very calm guy” who nonetheless responded with resolve when faced with discrimination. “George would make sure that things moved forward. He was phenomenal…just a powerful, powerful person,” says Thompson. Whether it was the elks or other discrimination that arose, “George was a guy that opened a lot of doors for a lot of people here for a long time.”

Henry says Gibbs “was not afraid to talk to anyone,” a trait that helped him advance and gain friends in virtually any environment. From officers aboard the ship with whom he built a rapport to those in need whom Gibbs brought home for a meal, “he would befriend anybody, he would talk to anybody.”

Gibbs’ years of extensive civic contribution earned him recognition within the community after he died at the age of 84 on November 7, 2000. A Rochester, Minnesota, elementary school was named after him, as well as a road in the city’s downtown. The Rochester NAACP, which he helped establish, created an award in his name.

And more than 7,000 miles south of snowy Rochester, a piece of the continent is now designated in his honor: In 2009, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names designated Gibbs Point, situated on the northwest corner of Gaul Cove on an Antarctic island known as Horseshoe Bay. It is a permanent homage to the young U.S.S. Bear mess attendant, and his historic first on the icy continent.