In the fall of 1983, a handful of women ate Chinese takeout in a tiny Washington, D.C. apartment, half of them seated on folding chairs. Each of the fortune cookies had been threaded with customized slips that hinted at the real reason the women were there: to get the first woman nominated as vice president by a major party.

“You will win big in ’84,” read the piece of paper inside Queens congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro’s cookie. The third-term representative, a second-generation Italian-American, was the evening’s guest of honor; the other women had concluded she was the right woman to do the glass-shattering. Their question to Ferraro: Was she game?

“This was not the power scene you would picture,” remembers Joanne Howes, then the executive director of the Women’s Vote Project and a member of the small group of behind-the-scenes activists, known as “Team A,” who worked to propel Ferraro into history books. At the time, national politics was even more an old boys’ club than it is today; just 24 of the 535 voting members of Congress and no governors were women. By those standards, the notion of a female vice president was audacious. “There’s no way,” Ferraro herself had said, with typical candor, at a closed meeting at the National Women’s Caucus three months earlier, “any presidential candidate is going to choose a woman as a running mate unless he’s 15 points behind in the polls.”

That’s almost exactly what happened. In the Democratic attempt to unseat President Ronald Reagan, former Vice President Walter Mondale, lagging by some 12 to 19 points, selected Ferraro as his running mate. The election ended poorly for the Democrats: Reagan and his vice president, George H.W. Bush, won in a rout, with all but one state voting for the incumbents.

Ferraro’s candidacy, however, showed the public that a woman could campaign stride-for-stride for national office. It would not be until 24 years later, when Senator John McCain chose Alaska Governor Sarah Palin as his running mate in 2008, that another woman would appear on a major party’s ticket. And now, 12 years after Palin, former Vice President Joe Biden’s selection of Kamala Harris as his running mate will make the California senator the second Democratic woman to become a vice presidential nominee. Looking back at Ferraro’s candidacy puts in harsh relief the strides women in politics have made as well as the gendered relics that remain part of the political conversation today. Here, compiled from sources including contemporaneous news clippings, Ferraro’s memoir, and interviews with players who were part of this history, is a look back at Ferraro’s exhilarating, much-scrutinized path to becoming a political standard-bearer.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e2/aa/e2aa51c5-b2a9-4c06-bbaa-18137bfe6f39/buttons.jpg)

I. “The gender gap” —first appearance of the term in the media, Washington Post, 1981

When, in 1980, former California governor Ronald Reagan ascended to the presidency, the exit polls showed two unusual data points: One, women voters turned out at a higher rate than men for the first time since they'd gotten the right to vote nationwide in 1920, and two, a small but significant disparity had emerged between who men and women voted for, with eight percent fewer women than men supporting Reagan. The National Organization for Women (NOW) and its president, Eleanor Smeal, looked at the exit poll data and dubbed the difference “the gender gap.” While the concept of the “gender gap” can oversimplify nuanced voter behavior, parsing the meaning of this gulf between men and women voters has become a mainstay of American elections ever since.

Popular consensus before the ’80s held that for the most part, women cast their ballots along the same lines as men, explains Susan Carroll, a senior scholar at the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers. When the 1980 race departed from this norm—and then state races in ’82 again showed women voters breaking more Democratic than men—feminist groups took note and made sure the media did, too. “The ‘women’s vote,’ a powerful new voting bloc, will make the difference in political contests,” wrote Smeal in her 1984 book, Why Women Will Elect the Next President. “The gender gap is the new wild card in political sweepstakes.”

Both the political right and left tried to determine how this new trend would play in the elaborate chess game of electoral politics. The Reagan White House worried it “could cause serious trouble for Republicans in 1984,” while feminist groups pressured lawmakers to foreground women’s rights issues in their campaigns and held voter registration drives. In Democratic circles, the idea of how a female candidate might exploit the gender gap started percolating. While some polls did indicate that a woman on the Democratic ticket might sway voters, then-CBS News pollster Kathy Frankovic explained in “The Ferraro Factor: The Women’s Movement, the Polls, and the Press” that the sum total of data yielded mostly muddy hypotheses. “There was no good evidence one way or the other about what difference it would make to put women on the ticket,” says Carroll.

All this unfolded amid an outpouring of feminist activism and shifting attitudes about women in politics. The women’s movement had just lost a hard-fought battle to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment before its deadline expired; the Supreme Court’s 1973 ruling on abortion rights in Roe v. Wade was still fresh. New York Representative Shirley Chisholm had become the first black woman to run for president 11 years prior, and in 1977, tens of thousands of women had gathered at the National Women’s Conference in Houston to brainstorm policy ideas that would improve the daily lives of American women. A 1983 Gallup poll found that 80 percent of Americans professed that they would vote for a qualified woman for president, a marked improvement since the question had first been asked just before World War II.

II. “And for Vice President…Why Not a Woman?” —TIME Magazine headline, June 4, 1984

The prospect of a Democrat putting a woman on the ticket was often placed in the context of electability: Would it help them unseat the incumbent President? When Reagan’s popularity was at its nadir in early 1983, the electoral calculus went something like this: A woman might help clinch a Democratic victory in a close race. Later, when Reagan’s approval ratings rebounded, the argument evolved. Perhaps rupturing the glass ceiling could generate enough enthusiasm to shake up the race in the Democrats’ favor.

In public, NOW pushed the idea, asking the six Democrats vying for the nomination at their national conference in the fall of 1983 whether they’d appoint a woman as their second-in-command, and the idea snared the media’s attention. In private, over Chinese takeout or in a House of Representatives meeting room, the women of Team A—as they’d come to call themselves—strategized how to place a qualified woman on the ticket.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e1/a7/e1a7ece2-25dd-4b9a-8a3f-04b5deb051fb/fullsizerender.jpeg)

All were feminists active in Democratic politics: Joanne Howes, the executive director of the Women’s Vote Project; Joan McLean, a House staffer; and Nanette Falkenberg, the executive director of the National Abortion Rights Activist League (NARAL). They wanted the eventual nominee to consider a woman for his running mate as a matter of symbolism and practicality, someone who would barnstorm barriers but also be seen as a viable candidate. “Like good strategists, we always [knew] you don’t always get what you want, but you may get something by going after that,” McLean remembers of their expectations. After reviewing the roster of experienced women politicians (an inherently short shortlist, notes Howes. Unlike the slate of women in 2020, “We didn’t have a whole lot of people in the arsenal.”), they landed on 48-year-old Geraldine Ferraro, an “up-and-coming-star” who represented New York’s Ninth District.

Ferraro’s path to politics involved night classes at Fordham Law in Manhattan while working a day job as an elementary school teacher in Queens, a stretch of time devoted solely to raising her children, and a return to the workforce at age 38 as a prosecutor for the Queens Special Victims Bureau. She adopted, “Finally, a tough Democrat,” as her campaign slogan in her first campaign for Congress.

McLean remembers the pitch the trio made to their mentor, the activist Millie Jeffrey, over a Sunday brunch:

“You look at her and you can imagine her as your best friend, as your sister, as your member of Congress, as somebody you want to listen to. She has a profile that many women voters have. She’s married; she’s a mother; she waited until her kids were older to run for public office, and she comes from Queens, which is a very diverse district, and she has a moderate to liberal portfolio. She’s a member of the leadership; the Speaker [Tip O’Neill] likes her, labor unions like her, she has been active on issues for older voters.”

Jeffrey, who had deep ties among labor, civil rights, and women’s rights activists, was convinced, and she’d drop Ferraro’s name in conversations with her peers when the topic turned to potential vice presidents. (Many of these discussions, it should be said, happened while the Democrats had yet to choose a suitable man for the top of the ticket.) Team A recruited Eleanor Lewis, Ferraro’s top aide, to join them as well.

Now they had to sell the would-be candidate herself on the idea. Ferraro, “flabbergasted and flattered,” agreed to toss her hat into the ring, but the possibility of her actually becoming a vice-presidential candidate seemed remote, she wrote in her memoir, Ferraro: My Story.

During the veepstakes, “I took advantage of the fact that people were talking about me, but I never, for one minute, really believed that it was going to happen,” she remarks in the documentary Geraldine Ferraro: Paving the Way.

The “Ferraro snowball,” as one Washington Post reporter called it, had been set into motion in the months between Team A’s takeout meeting with the congresswoman and the summer of 1984. Team A’s maneuvering helped Ferraro become the first woman Democratic platform committee chair, tasked with wrangling her party’s factions into articulating a single policy vision for the election. In May, Tip O’Neill endorsed Ferraro as a potential vice president in the Boston Globe.

Newspapers and magazines recounted her life story: how she’d been named after her older brother, Gerard, who had died as a toddler; her father’s death when Ferraro was only 8; her mother’s return to crocheting beads onto dresses to support the family; her Catholic-school education; how the particularly reprehensible crimes she’d seen as a prosecutor propelled her into public office. They’d note her frankness (‘Hey, listen, it’s very heady stuff. But I know full well the only reason I’m on that short list is because I’m a woman,” she told the Washington Post), feather-duster platinum hair, her figure.

And all this unfolded before the Democrats had even settled on a nominee. It wouldn’t be until June that Mondale, the former Minnesota senator who had served President Carter as vice president, would lock up the race he was an early favorite for, outlasting Colorado senator Gary Hart and civil rights leader Jesse Jackson after a grueling primary.

Ferraro had drawn attention, Sheila Caudle wrote in Ms. Magazine’s July 1984 issue, because

“She is the sort of pragmatic politician that the voting populace—and the men in the back rooms—could find most palatable: Attractive, but not beauty-pageant beautiful…A modern career woman, but one steeped in Old World values. Charismatic. Forceful, but not overbearing. The best-prepared of a well-prepared lot. Loyal to the party. At ease in the old-boy network. She is, in essence, something of a fairy-tale candidate.”

III. "I am proud to say that the WHITE MALES ONLY NEED APPLY sign is no longer posted outside the White House." —Geraldine Ferraro, speaking at an Alpha Kappa Alpha convention in Washington, D.C., July 1984

Once Mondale became the presumptive nominee in June, he began interviewing a roster of Democrats—including Ferraro, then-mayor of San Francisco Dianne Feinstein, Los Angeles mayor Tom Bradley and San Antonio mayor Henry Cisneros—from significantly more diverse backgrounds than all of the white men elected vice president to date. Always a realist, “she was convinced after the interview with Mondale that it wasn’t going to happen,” remembers McLean; according to reports, Feinstein had impressed the Minnesotan, while a Southern moderate like Texas senator Lloyd Bentsen made electoral sense.

On July 11, Mondale picked up the phone from his living room. “Here goes,” he reportedly said, and dialed up Ferraro’s San Francisco hotel suite, where she was busy preparing for the convention to begin.

“We were sitting in the living room, and she went into the bedroom to take the call and came out just smiling,” remembers Dave Koshgarian, Ferraro’s congressional legislative director and speechwriter. “How does it feel to be a part of history?” Ferraro asked the room, after accepting the job. The race for the White House was on.

“I would never have accepted Mondale’s offer if I didn’t think we would win. I’m not into losing or being offered up as a sacrifice,” Ferraro wrote in her memoir.

Mondale, with Ferraro at his side after a covert late-night flight, told the assembled press in St. Paul, “I looked for the best vice president, and I found her in Gerry.”

“Thank you, Vice President Mondale,” said Ferraro after his speech. Then she added, “Vice president has such a nice ring to it.”

“It was magical,” recalls McLean, who had flown from California to witness the announcement. “What struck me the most was how delighted Vice President Mondale was with his choice. He beamed. He loved being the person to do it.”

The Associated Press article on the selection began:

“The usually cautious Walter Mondale has laid down the biggest wager of his political life, gambling that the nomination of Geraldine Ferraro as his running mate will energize and attract more voters than it loses. It is a high-risk strategy designed to upset Ronald Reagan. For more than a year, feminists have been arguing that naming a woman would ‘maximize the gender gap,’ electrify otherwise indifferent voters—particularly women—and give Mondale the boost he needs to overcome what some polls say is now a 19-point Reagan margin.”

In his memoir, Mondale himself discussed the two threads of the decision to renovate the image of the white, male vice president. Through his eyes, the selection was a last-ditch, long-shot political calculation but also a brave departure. The idea of a woman vice president almost got torpedoed after NOW’s public threat of a convention-floor rebellion caused Mondale advisors to worry about the selection being seen as a sop to “special interest” groups—a coded way of saying feminists, organized labor and racial minorities—for which he’d incurred primary criticism from rival Gary Hart. But his liberal view of the country won out. “I thought that putting a woman on a major-party ticket would change American expectations, permanently and for the better,” Mondale wrote.

IV. “The High Point of the Democratic National Convention” —The Associated Press

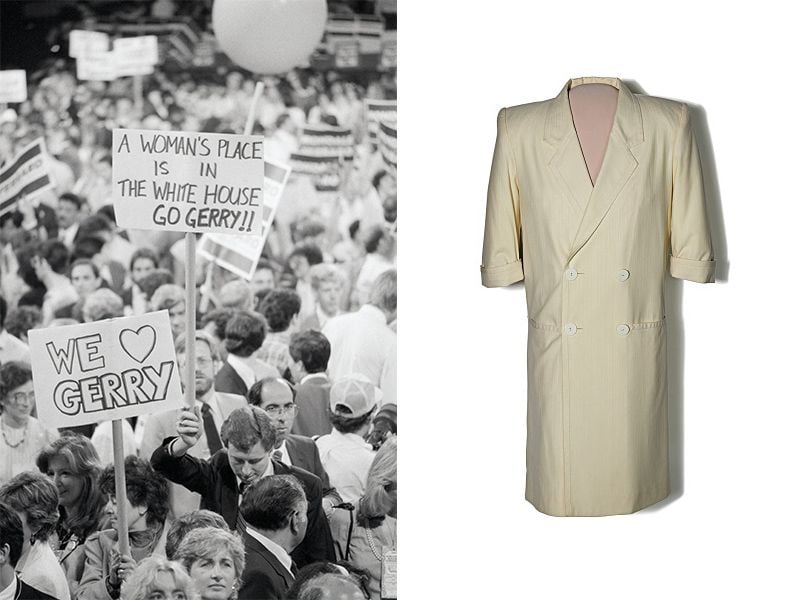

In their remarks at Ferraro’s announcement press conference, the duo recognized the historic nature of it all, but they also emphasized that theirs was a “campaign for the future.” When the faithful convention crowd amassed just days later on the Moscone Center floor to see Ferraro formally accept her nomination, it seemed like a peephole into that hoped-for liberal future, says Joanne Howes. Many of the male delegates had given up their floor passes to a diverse group of women.

When the New Yorker, dressed in suffragist white, strode onto the stage, the crowd went wild. Ferraro uttered the words, “I proudly accept your nomination for Vice President of the United States,” and then had to pause for more than a minute for applause and cheers of “Ger-ry.” Foundational feminist Betty Friedan, who had been hesitant to push for a female nominee, fearing the accomplishment would be solely a symbolic gesture, wrote to Ferraro: “It was a peak experience for me that day in San Francisco. I was kvelling.”

Ferraro rocketed to celebrity. Her congressional office, she wrote in her memoir, received some two or three thousand letters each day.

In one, a medical worker in New York wrote: “While on my way to work this morning, I turned on the car radio and heard what has got to be some of the best news I’ve heard in a long time. As a matter of fact, I was so overcome with joy for you that I started crying.” Longtime Republicans congratulated her; fans wrote from New Zealand, Saudi Arabia and Italy.

Other women harbored doubts. “We [women] look at ourselves and think, ‘I couldn’t handle it so I don’t know if she could, either,” Tennessean Carol Roberts said to New York Times reporter Maureen Dowd, who was surveying everyday voters. Roberts continued, “Maybe that’s the wrong thing to do. Men don’t do that.”

“White women have got their representative,” a black woman delegate to the convention told Gloria Steinem for Ms. magazine, “and that makes me proud as a woman, but I need to know that she’s going to fight and stand for me.”

After the convention, the polls sloped up momentarily, offering a glimmer of hope. The week Ferraro accepted the nomination, one Gallup poll even showed the Democrats neck-and-neck with Reagan, though that result would prove to be a blip in the Democrats’ consistently trailing numbers.

V. “My husband does not do business with organized-crime figures,” —Ferraro to the Los Angeles Times

Three weeks later, the sense of post-convention momentum deflated as the national spotlight on Ferraro also put its glare on her family: her mother, in honor of whom Ferraro had decided to use her maiden name professionally; her three children, who took time off from college and work to campaign; and especially her husband, John Zaccaro, and his real-estate business.

At the crux of the scandal was this: Ferraro and Zaccaro had filed separate tax returns, and she planned to release hers, while he did not. When, in mid-August, Ferraro made this known, it was a journalistic tripwire, spawning headline after headline.

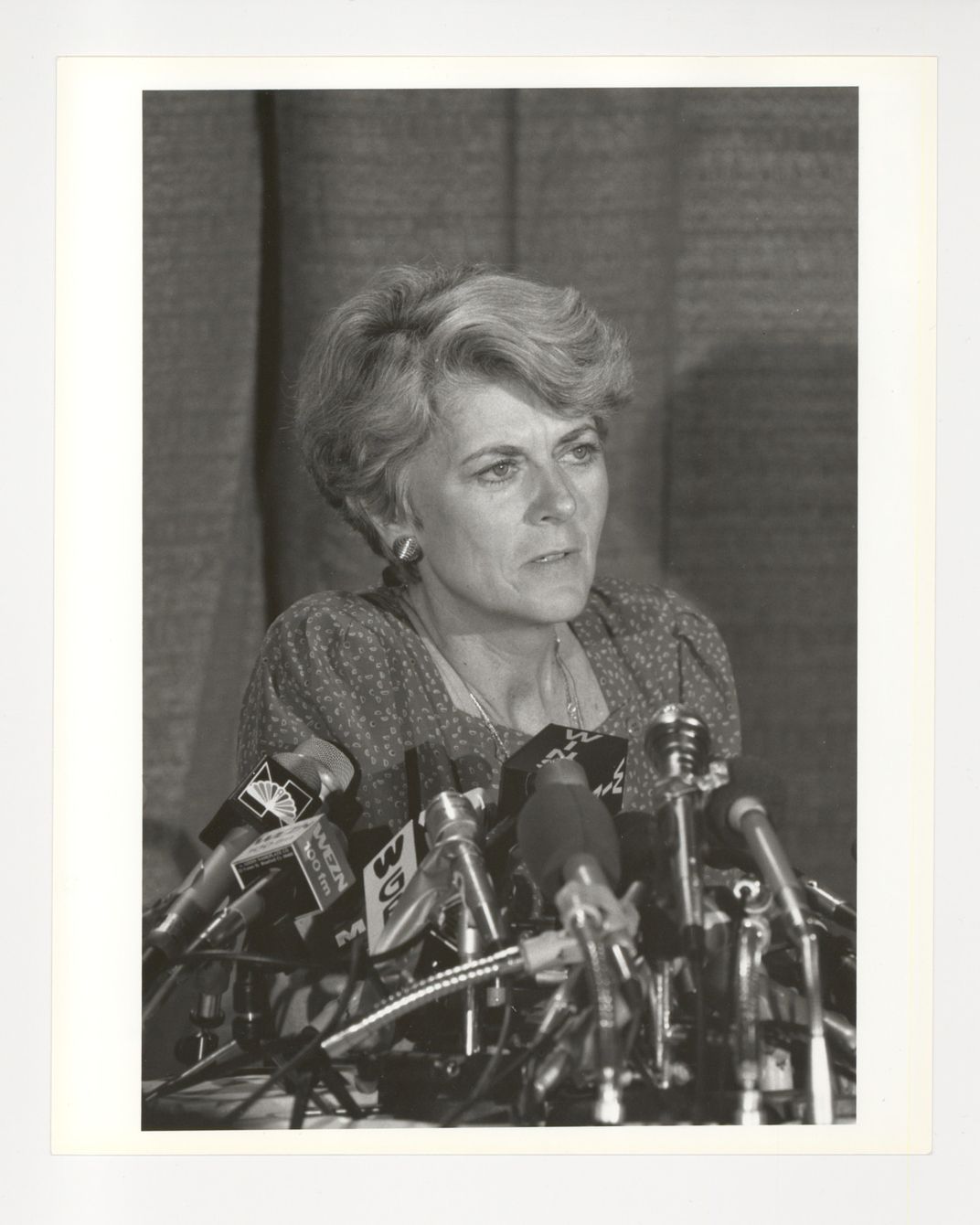

Under mounting pressure, Zaccaro agreed to make his tax returns public. Ferraro held a marathon press conference after their release, answering questions from a crowd of more than 250 journalists. The lasting image of that press conference is Ferraro, eyes intent, a swarm of microphones arrayed before her.

“Grilling can’t melt her,” proclaimed the New York Daily News, while the Washington Post called her “spirited.” But the Ferraro-Zaccaro press frenzy persisted. Stories cropped up examining tangential connections between Zaccaro’s business and organized crime. These articles didn’t necessarily pass journalistic muster at papers like the New York Times, but they still catalyzed the news cycle. Mid-flight on the campaign plane, Ferraro found out via a New York Post article that her parents had been arrested for a numbers racket shortly before her father’s death 40 years earlier. Afterward, the press asked whether she’d cried when reading the news.

Many of these stories appeared in the pages of the New York Post and Philadelphia Inquirer, which at one point had no fewer than 25 reporters investigating the family’s finances. As the Daily Beast reported in 2018, this was no coincidence. Two Reagan campaign aides oversaw a covert effort to comb through the Ferraro-Zaccaro records, and then seeded stories with those two papers, including the piece about her parents.

It wasn’t lost on Ferraro that the third-degree-of-separation reports about her husband and organized crime may have gained unwarranted traction because of their Italian-American heritage, which reporters and politicos alike described as “ethnic.” “I don’t think the press…would have put that kind of energy into it if we’d been talking about somebody called ‘Jenkins,’” Ben Bradlee, the storied Washington Post editor who’d overseen its Watergate coverage, later told the Los Angeles Times.

Ultimately, the taxes revealed nothing deeply nefarious. Zaccaro did plead guilty in January 1985 to a misdemeanor charge for submitting fraudulent information as part of a mortgage application. In August of 1984, he was removed as a court-appointed conservator because he had lent money from the estate to his own business, then repaid it. But, as Mondale later reflected to the New York Times, the snowballing scandal cost the already struggling campaign time and momentum.

On the campaign trail, however, Ferraro added much-needed charisma, a type of wry familiarity that drew 12,000 people to her first rally. A New York Times reporter assigned to the campaign, Jane Perlez, likened her effect on audiences to that of a Kennedy scion. “Gerry was a very real, down-to-earth, relatable person. There was no artifice to Ferraro,” remembers Koshgarian, her staffer.

Some of her advocates felt that the Mondale campaign wasn’t making full use of her mince-no-words dynamism. In her magazine, Ms., Steinem wrote, “I’m struck again by the difference between this reality of huge, cheering crowds touched by Ferraro’s magic, and the rest of the world that barely knows who she is.”

The single vice-presidential debate in late October offered the campaign a high-stakes chance to familiarize the public with the magnetic, witty Ferraro that the media often captured as well as a woman who was serious and prepared to be president.

VI. "Now that was fun" —Geraldine Ferraro, after the October 11 vice-presidential debate

“What she went into [the debate] really wanting to prove was that she was very substantive and very knowledgeable and even-tempered,” recalls Donna Zaccaro, her eldest daughter. Ferraro, who’d once confessed her weak spot was foreign policy, would be going toe-to-toe with the current vice president, ex-CIA director and former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, George H.W. Bush. After studying gargantuan briefing books prepared by advisers like future secretary of state Madeleine Albright, she rehearsed rigorously. The lawyer who’d helped Mondale with his own vice-presidential debate eight years prior, Bob Barnett, oversaw Ferraro’s debate prep. Barnett, who’d go on to ready many other Democratic candidates—including both Clintons—for debates, says Ferraro would joke about throwing Bush off-kilter: “For the opening handshake, she threatened to kiss the vice president full on the lips...,” he remembers. “She also threatened to greet him by his not-favored nickname—‘Poppy.’” (For the real deal, Ferraro went with a handshake and no monikers.)

About midway through the debate, Ferraro and Bush fielded questions from a moderator about abortion. During the campaign, the congresswoman had been careful not to position herself as a women’s-issues candidate, but her pro-choice stance had incurred rare political criticism from an archbishop, and protestors routinely aired their outrage at her appearances and on the steps of the Catholic church her family attended. “I am a devout Catholic,” she answered, “I would never have an abortion, but I [am] not quite sure if I were ever to become pregnant as a result of a rape if I would be that self-righteous…I will accept the teaching of the church, but I cannot impose my religious views on someone else.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9a/6b/9a6b9fc5-351c-4a93-8d56-27cb06b066bc/gettyimages-541679014.jpg)

Another clash with Bush made for memorable headlines: “Let me help you with the difference, Mrs. Ferraro, between Iran and the embassy in Lebanon,” Bush said, in response to Ferraro’s criticism of the administration’s reaction to the suicide bombings of an American embassy. “Let me just say, first of all, that I almost resent, Vice President Bush, your patronizing attitude that you have to teach me about foreign policy,” she said, an unrehearsed rejoinder.

Her team judged the debate either a win or a tie. Polls showed another gender gap: A majority of men viewed Bush as the victor, while women were split. “In the Bush-Ferraro meeting, the super-credentialed Brahmin Yalie behaved like a frightened oaf, while the Italian-American ex-housewife displayed calm, breeding, and self-possession,” came political analyst Morton Kondracke’s assessment in the New Republic.

Bush’s camp wasn’t as full of acclaim. “She’s too bitchy,” his press secretary Peter Teeley told the Wall Street Journal. A hot mic at a subsequent event caught Bush saying he “tried to kick a little ass last night,” a “locker room comment” that “did him a lot of good with Johnny Lunchbucket and Johnny Sixpack,” in the words of Republican consultant Rich Bond.

Teeley’s crass remark was far from the only overt sexism Ferraro faced. In Mississippi, she was asked whether she could bake a blueberry muffin; in one "Meet the Press" interview, moderated Marvin Kalb questioned both “Could you push the nuclear button?” and whether Mondale would have chosen her if not for her gender. Ferraro parried back—" I don’t know if I were, if I were not a woman, if I would be judged in the same way on my candidacy, whether or not I’d be asked questions like, you know, are you strong enough to push the button. . . .” and then move on, but decades later, she labelled the media’s treatment of her and her family as sexist. “In 1984, I couldn't say, ‘Stop it,’” she explained to Newsweek. “Because I couldn't look like I was whining or upset about it.” Within the campaign, tensions arose; after she wasn’t given the chance to weigh in on their campaign schedule in an early strategy meeting, Ferraro suggested Mondale’s staffers imagine her as “a grey-haired Southern gentleman” and treat her accordingly.

VII. An “overwhelming defeat” —on the New York Times front page, November 8, 1984

At some campaign stops, Ferraro would amp up the crowds by asking them, “The pollsters and pundits say we can’t win in November…But I want to take my own scientific, objective survey right here. Are we going to win in November?’

“‘YES!’ the crowd would roar,” she recounted in her memoir.

Instead, the Democrats went down in one of the worst defeats in presidential election history, with Reagan and Bush winning the electoral college by a count of 515-13. (Only Minnesota and the District of Columbia voted for Mondale and Ferraro.) In Ferraro’s home state of New York, the incumbents won by 7.5 points.

The gender gap persisted—Reagan and Bush were more popular with men than women. Still, the majority of women ultimately voted Republican. After all, the incumbent president was popular and the economic outlook chipper. Exit polling revealed that Ferraro’s presence on the ticket, like that of almost all vice presidential candidates, made little difference in voters’ choice. Just as previous research had suggested, simply having a woman represented wouldn’t automatically win over the rest of her gender.

“Am I disappointed in American women?,” Ferraro asked rhetorically in her concession speech. “No, I have confidence in us. We’re on our way, we’re not monolithic, we have wonderfully independent minds.”

“Campaigns, even if you lose them, do serve a purpose,” she said. “My candidacy has said the days of discrimination are numbered. American women will never be second-class citizens again.”

VIII. "All-male control of national political leadership is no longer written in stone, or engraved on voting machines" —Bella Abzug and Mim Kelber, in a New York Times op-ed

After the race, Ferraro was a prominent face for women in politics. “Gerry was smart, funny, beautiful, compassionate, creative, and a lot of fun. And that shone through when the country was introduced to her,” says Barnett. He represented her memoir—the 1985 equivalent of Hillary Clinton’s What Happened—which sold for $1 million and became an early example of a politician-as-celebrity bestseller.

Ferraro did not hold elected office again. She ran unsuccessfully for the Senate twice and became the United Nations Human Rights Commission ambassador. In 2008, she campaigned for Hillary Clinton and then stepped down from her post after drawing fire for her remark that “if [Barack] Obama was a white man, he would not be in this position.” But her legacy is no small thing: She laid a template for other women in politics to follow.

“She felt tremendous responsibility,” says her daughter Donna. “She felt that if she did a credible job, then she would change the perception of what people thought was possible for women.”

Her candidacy did spark enthusiasm: People donated to and volunteered for her campaign in droves, and women expressed heightened interest in politics after her run. Team A also made note of women’s mobilization and wondered how they could expand the pool of women running for higher office. Several of them became some of the “founding mothers” of EMILY’s List, a prominent PAC that funds Democratic women who support reproductive rights.

“There’s no question that EMILY’s List is a direct outgrowth of the political force we saw in women as voters and potential voters,” says Howes. She sees the “crowning achievement” of Ferraro and Team A’s joint legacy as the 2018 election, in which a record number of women, many backed by EMILY’s List, won office and flipped the House of Representatives to Democratic control.

Kamala Harris is the nation's third woman vice presidential candidate from a major party. “We’re edging—inching—towards parity” for women in politics, with some plateaus along the way,” Carroll says. Women currently constitute under one-fourth of Congress. (83 percent of them are Democrats, 17 percent Republicans.)

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History political historian Lisa Kathleen Graddy, who curated the museum’s exhibit on suffrage, says Ferraro’s candidacy mirrors the challenges women have faced professionally, in the ’80s and today. “It highlights the ambivalence, the nervousness, that even supporters felt about women taking the next step…Some people felt, and still feel, fearful of competent, ambitious, powerful women. And there is still lingering illusory idea that women candidates should somehow be a gender blind choice instead of embracing the obvious value of specifically bringing women's perspectives.”

“The real test of my candidacy will come when the next woman runs for national office,” Ferraro says in the documentary produced by her daughter Donna, in a 2010 interview filmed one year before her death from multiple myeloma. “Only then will we know… if she, too, is going to have to be better in order to be judged equal.”

Editor's Note, August 11, 2020: This article has been updated to reflect the selection of Kamala Harris as Joe Biden's running mate.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(345x105:346x106)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/30/15/3015a7b4-dc6c-4f91-b431-935e8c338413/ferraro-mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9f/87/9f87bf36-8d11-4cc6-a2f2-bffdb3e09fe7/ferraro-longform-opener.jpg)