It takes less than ten minutes to walk the length of the cobblestone street of Judenstrasse ("Jew street") in the sleepy East German town of Lutherstadt Wittenberg. On the street’s western end stands the Wittenberg Schlosskirche, or Castle Church, where, according to legend, Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses to the door on October 31, 1517. Nearby is an enormous 360-degree panorama installation by a Leipzig artist celebrating Luther for democratizing the church. A few blocks to the east, behind the old market square, is the Stadtkirche, also known as the Wittenberg Town Church of St. Mary’s. It was here that Luther delivered the majority of his sermons, and it’s also the site of the first celebration of Mass in German instead of Latin. Wittenberg in general—and the Stadtkirche in particular—is considered the heart of the Protestant Reformation.

Around the back of the Stadtkirche, in a carved sandstone sculpture set into the facade, a rabbi lifts the tail of a pig to look for his Talmud. As he stares, other Jews gather around the belly of the sow to suckle. Above this scene is written in flowery script: “Rabini Schem HaMphoras,” a mangled inscription intended to mock the Hebrew phrase for the holiest name of God.

The sandstone sculpture is a once-common form of medieval iconography called a “Judensau,” or “Jew’s pig.” Its existence predates the Nazi period by nearly 700 years. Sculptures of Jews and pigs started appearing in architecture in the 1300s, and the printing press carried on the motif in everything from books to playing cards well into the modern period. Today, more than 20 Judensau sculptures are still incorporated into German churches and cathedrals, with a few others in neighboring countries. At least one Judensau—on the wall of a medieval apothecary in Bavaria—was taken down for its offensive nature, but its removal in 1945 is thought to have been ordered by an American soldier. The Judensau in Wittenberg is one of the best preserved—and one of the most visible. The church is a Unesco World Heritage site.

Over the past few years, the debate over this anti-Jewish sculpture has become newly urgent. Far-right nationalism has been on the rise throughout the country, but especially in Saxony-Anhalt, the state where Wittenberg is located. In August 2018, after Iraqi and Syrian asylum seekers were arrested for stabbing a German man, thousands of neo-Nazis from around the country descended on the Saxony-Anhalt city of Chemnitz and rioted for a week. In one attack, a Jewish restaurant owner said dozens of assailants threw rocks, bottles and a metal pipe at his business and shouted, “Get out of Germany, you Judensau!”

In 2016, the last time Saxony-Anhalt held an election, the far-right ultra-nationalist party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) debuted at 24.2 percent of the vote. In September 2019, when the neighboring state of Saxony held its most recent election, the AfD received 27.5 percent. The following month, in October 2019, a far-right gunman attempted to attack a synagogue in the town of Halle, about an hour southwest of Wittenberg. His shots killed two people and wounded two others.

At the same time, Germany’s process of atonement for its war crimes is widely recognized. After World War II, the country paid nearly $90 billion in reparations, mostly to Jewish victims. Monuments and memorials in major cities pay tribute to the Jewish dead. Along with the larger memorials and concentration camp sites, there are stolpersteine in 500 German towns and cities, including on nearly every street corner in Berlin—small brass plaques bearing Jewish names, set in the ground outside the homes from which the residents were taken.

These acknowledgments began with an Allied-led program called Entnazifizierung, or de-Nazification. It started when Americans captured Nuremberg in 1945 and blew up the giant swastika overlooking Hitler’s parade grounds. Street signs bearing the Nazi names were removed. War criminals were tried and convicted. Konrad Adenauer, the first chancellor of West Germany, abandoned the official de-Nazification program, but the generation of Germans who came of age after the war earnestly resumed the task. As recently as a few months ago, a 93-year-old former officer at Stutthof concentration camp was tried and found guilty of 5,230 counts of accessory to murder.

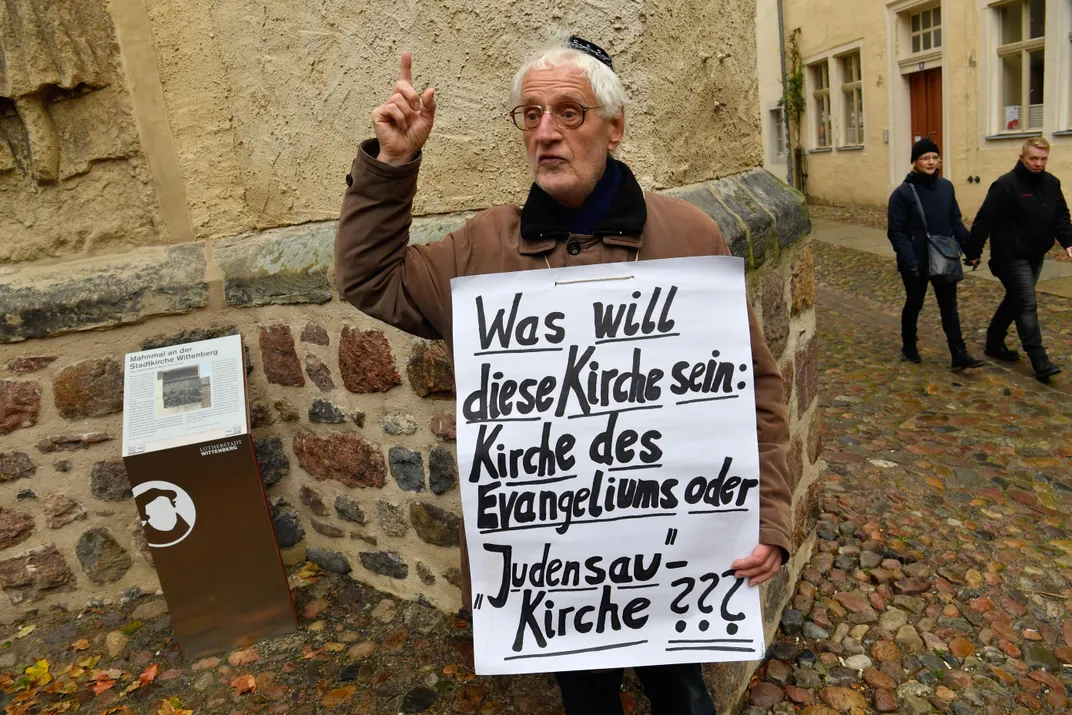

Today, raising one’s arm in a Nazi salute is illegal in Germany. So is calling someone a Judensau. Yet the Judensau sculptures remain. For decades there have been petitions and calls for their removal, but none has succeeded. Michael Dietrich Düllmann, a 76-year-old pensioner, is hoping to fix that.

* * *

In many ways, Düllmann hasn’t changed much since the night in 1968 when he entered a West German church with an ax, locked himself inside and chopped up four plaques dedicated to German World War I soldiers. He left behind a pacifist message, painted in red: “My house should be for prayer for all, but you made it a hall of fame for your crimes.”

Today, Düllmann is lithe and spritely and eager to talk. A story about his childhood leads to an impassioned account of Germany after World War II. “Shame!” he says. Shame on the church, on those who defend the Judensau. Above all shame on the way Germany has handled its history with the Jewish people.

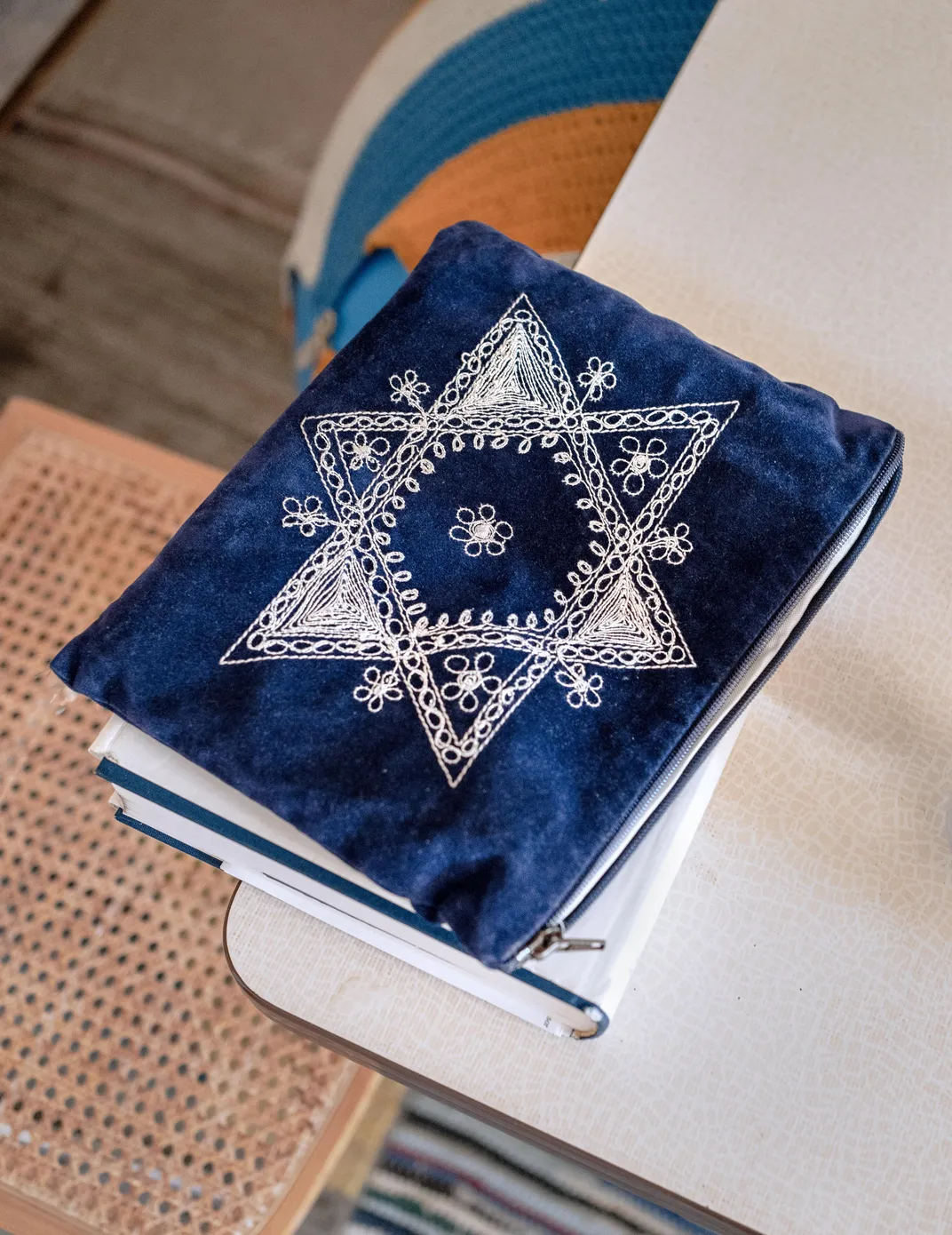

He lives in a one-bedroom apartment in a large concrete building on the outskirts of Bonn. He has no TV or computer. “My world is the world of literature, not the world of the internet,” he tells me before reciting “Death Fugue,” a poem by Holocaust survivor Paul Celan. Menorahs line his shelves, and in a far corner, a dresser is set up for his weekly Shabbat celebration.

Born to a Protestant family in 1943 in the Eastern German town of Halberstadt, Düllmann was the son of a Nazi soldier who was imprisoned by the Russian Army on the Eastern Front. His father did not return to his family after his release, settling instead in the West, which was divided from East Germany in 1949. His mother’s tuberculosis and subsequent stay in a sanatorium delayed the family’s move to the West until 1953. But his parents never reunited, and he spent much of his childhood with a foster family.

He learned to read from a thick family Bible printed in Gothic script. He says this sparked his early interest in theology and religion. But as a teenager he did poorly in school and rebelled. In 1959, he went to live with his mother near the West German town of Wolfenbüttel and managed to complete high school. He began to learn about Hitler, National Socialism, the Holocaust. He confronted his mother, who admitted she voted for Hitler in 1933, but he never had the opportunity to confront his father, who died in 1966.

By that time, Düllmann was enrolled at the University of Göttingen. As a theological student, he was exempt from service in the military, but in 1967 he nevertheless chose a community service alternative and worked as a caretaker in a nursing home for 18 months. In 1971, he saw an advertisement by a Swiss student group looking for volunteers to travel to Israel to work on a kibbutz. He decided to sign up, and dropped out of the university.

Such a period of discovery is a typical story for members of what Germans call the ’68 generation. Children of former Nazis confronted the sins of their parents, becoming peace activists in solidarity with the civil rights and antiwar movements in the United States, France, Czechoslovakia and elsewhere. “So many of our parents’ generation did not want to speak about the Nazi period,” he says.

On the kibbutz, Düllmann did all manner of menial labor, but for him it felt like paradise. He was meant to stay three months but remained four years, living and working at four different kibbutzim. At one of them, he met Gina, a German Jew who had grown up in Brazil after her family fled Hitler’s rise in the 1930s. He says his decision to convert to Judaism came to him on a walk. “The nature was blooming, everything was so beautiful,” he said. He was in love.

He wanted to convert in Israel, but the process was long there, and he was feeling pressured to become a West Bank settler. Instead, he returned to Germany in 1975 to convert to Judaism under the auspices of a rabbi who was a Holocaust survivor, and Gina came with him to get married. The marriage didn’t last, but he and Gina remain close.

He began to study politics, but ended his studies again, this time because he had a young family to support. As he worked a number of factory jobs, he often participated in demonstrations against nuclear power, arms sales and environmental degradation. In 1987, he campaigned against the building of a hotel on the site of a synagogue in Bonn that had been destroyed on Kristallnacht, living on the site for several months and going on a hunger strike.

In 1990, he says, police knocked on his door and asked if he was ready to pay fines relating to his many previous arrests at demonstrations throughout the ’80s. He refused. “I did not want to criminalize the peace movement by paying these fines,” he explained. He was then imprisoned and conducted a 64-day hunger strike while in jail. Doctors brought in were horrified at his deteriorating health. After his release, he began training to become a geriatric care nurse, a job he held for 18 years until his retirement in 2009.

In 2017, while Düllmann was in Wittenberg rallying for the Judensau sculpture to be taken down, a group of nuns from Leipzig approached him and asked if he would consider taking the matter to court. He took up the charge wholeheartedly. When it came to fighting the church, he quickly realized, a lawsuit was a subtler tool than an ax.

In Germany, legal costs must be paid upfront and are recuperated only in the event of a victory. Düllmann has paid more than 50 percent of the legal costs himself, taking them out of his pension of €1,150 per month. The rest has been donated by supporters of his cause.

His legal case hangs on defamation laws in Germany. Düllmann argues that the Judensau sculpture should be removed because it defames and offends the Jewish community of Germany. But for Düllmann, the fight is about much more than a single defamatory image. It is a fight for the heart of German culture, of which Luther is a foundational part. “All German culture was poisoned by him with hatred of Jews and anti-Semitism,” he says, pointing out that Luther played an important role in the ideology of the Third Reich.

“Luther was once a hero to me,” he says, “and is now my opponent.”

* * *

That Martin Luther hated Jews is not much of a historical question. He was more sympathetic in his early years, lamenting that the church “dealt with the Jews as if they were dogs rather than human beings.” But after years of trying and failing to convert them to Christianity, he wrote several lengthy tirades against the Jewish people. In one major treatise, “On the Jews and Their Lies,” he called upon Christians to burn Jewish homes, schools and synagogues and destroy Jewish prayer books.

To modern ears, that might sound like a dead ringer for the Kristallnacht pogroms of 1938. Luther’s defenders argue that his prescription was “anti-Jewish” rather than “anti-Semitic,” an attack on the religion rather than the ethnic group that practiced it. They insist that anti-Semitism, as Hitler preached it, relied on 19th-century race theories and therefore has nothing to do with Luther’s religious critique.

That distinction is largely artificial, says Thomas Kaufmann, a Protestant theology professor at the University of Göttingen and author of the 2014 book Luther’s Jews. Even though medieval attitudes preceded modern biological theories about race, he sees them as “proto-racist anti-Semitism.”

“By this I mean, for example, statements made by Luther like those that say, baptized or not baptized, Jew remains Jew,” Kaufmann told me. “This is heresy, because from a theological standpoint, the only difference between a Christian and a Jew or a non-Christian is baptism. And with a statement like this, Luther makes clear that a Jew can never be a Christian simply because he was born a Jew.”

Historians estimate that the Wittenberg Judensau was installed two centuries before Luther, around 1305, though the exact date is disputed. The motif appeared in ecclesiastic architecture from the 13th to the 15th centuries. A church was the most prominent architectural feature of many medieval towns, so it acted not only as a meeting place but as a billboard for communal values. Kaufmann suggests that a Judensau was a warning to Jews—a clear sign that they were not welcome.

Luther himself praised the sculpture on his home church in a 1543 text called “Of the Unknowable Name and the Generations of Christ.” Throughout the tract, he denounced Jewish beliefs about a hidden, powerful name for God—a kabbalistic teaching that Jews refer to as the “Shem HaMephorash” (the explicit name). “Here in Wittenberg, in our parish church,” Luther wrote, “there is a sow carved into the stone under which lie young pigs and Jews who are sucking; behind the sow stands a rabbi who is lifting up the right leg of the sow, raises behind the sow, bows down and looks with great effort into the Talmud under the sow, as if he wanted to read and see something most difficult and exceptional; no doubt they gained their Schem Hamphoras from that place.” The inscription “Rabini Schem HaMphoras” was installed above the sculpture 27 years later, in Luther’s honor.

No one I spoke to denied that the Judensau represents centuries of violent oppression. So why does it remain when Nazi artifacts, which represented only 12 years of persecution, were so thoroughly erased from public places?

* * *

English has two words—“monument” and “memorial”—to describe a structure meant to remind viewers of a person or an event. The two are used so interchangeably that it’s hard to describe the difference. But there’s no English word to describe an installation that apologizes for the past—perhaps because, until recently, America and Britain tended not to build them. The memorials for Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King Jr. in Washington, D.C. both recognize shameful episodes in American history—slavery and segregation—but only in the course of celebrating great men. One reason Confederate monuments are so controversial is that Americans can’t agree on whether they glorify the past or simply represent it.

In Germany, there’s less ambiguity around that question. German has several words for memorials. An Ehrenmal is a monument built to honor its subject (ehren means “to honor”). A Denkmal commemorates an event, like a battle, while a Gedenkstätte is a place of reflection and contemplation. Both of those words contain the root denken, “to think.”

Some monuments are also called Mahnmals—warning signs or admonitions never to repeat a horrendous part of history. The Dachau concentration camp is one of many sites throughout Germany that now stands in this spirit. Tour guides lead visitors around the grounds, past the mass graves, and under the gate that still bears the infamous slogan Arbeit macht frei—“Work sets you free.” The preservation of this camp, and other significant Nazi sites, is championed by those who want the world to remember the crimes that took place there.

The Jewish American author Susan Neiman praised Germany’s approach to these sites in her 2019 book Learning From the Germans. But she takes issue with the Wittenberg sculpture. “Monuments are visible values,” she told me. “And the question is what kind of values have they retained? Not whose feelings are they hurting, rather what kind of values are they showing in this very important historical church?”

In the 1980s, the Wittenberg church tried to solve its Judensau conundrum by turning the site into a Mahnmal. The church went through a renovation in 1983, in honor of Martin Luther’s 500th birthday. After five years of deliberation, those in charge of the project decided that the Judensau would remain—but they would add a memorial to the Jewish people. Unveiled in 1988, it is now installed on the ground in bronze. Two crossing lines are surrounded by text that reads: “The proper name of God, the maligned Schem-ha-mphoras, was held holy by the Jews long before the Christians. Six million Jews died under the sign of a cross.” Alongside those German words is a Hebrew quotation, the beginning of Psalm 130: “Out of the depths I cry unto Thee, O Lord.”

The whole installation lies flat on the ground, but it’s designed to look as though it’s being pushed upward by something bubbling up from underneath. Friedrich Schorlemmer, the former pastor of the Schlosskirche down the street, explains the significance of the image on the church’s website. “You can’t cover up injustice,” he writes. “The memory springs up from the rectangular slabs.”

Schorlemmer’s own biography parallels Düllmann’s. Born in 1944, one year after Düllmann, to a Nazi doctor on the Eastern Front, Schorlemmer was also intensely active in the peace movements of the ’60s and ’70s. He became a dissident pastor and a celebrated figurehead in movements for human rights, pacifism and the environment. Under the East German regime, his outspokenness put him under close observation by the Stasi, the infamous East German secret police. Both Schorlemmer and Düllmann have spent their lives wrestling with the past, horrified at their parents’ generation.

But they’ve ended up on opposite sides of the Judensau debate. Schorlemmer was among those who fought for the installation of the memorial. He considers it a hard-won show of justice and remembrance for German Jews. The current pastor at the Wittenberg Stadtkirche church itself, Johannes Block, feels the same way: “It is an admittedly paradoxical way of achieving a good goal with an evil object, namely dealing with history.” Objects placed in a museum “fade into oblivion,” as he put it. The church made the decision not to hide its own shameful legacy but rather to accept accountability.

When the Jüdische Allgemeine, a German Jewish paper, asked Block in February about the original anti-Semitic sculpture, he replied, “I feel shame, anger, and horror when I look at it. But it’s about the correct handling of this terrible legacy.” In recent years, the church has gone a step further, posting an information panel about Judensau sculptures and their role in history. In its three paragraphs of text, the new sign acknowledges the persecution of Jews in the area and briefly mentions Martin Luther’s anti-Semitic writings.

But when I spoke to Block about the original sculpture, his approach seemed circuitous in its own way. He corrected me several times when I called it a “Judensau.” That term, he insisted, only came about in the 1920s as a way to defame Jews and therefore “has nothing to do with the middle ages.” He preferred the term “Wittenberg Sow.” When I asked him about what should be done with similar sculptures still standing throughout Europe, he said he would recommend that the others add the kind of context the Wittenberg church has added. Still, as the leader of the most important historic church in Protestantism, he hasn’t vocally campaigned for such an undertaking.

When I asked why a swastika should be removed or placed in a museum and a medieval Judensau should not, he mentioned a series of Nazi-era church bells that have been the subject of controversy and court battles around Germany. In the northern Germany town of Schweringen, after a parish council decided to keep using their bell in 2018, activists sneaked in just before Easter and sanded the swastikas and the Nazi inscription off the metal surface. They left behind a note calling their act a “spring cleaning” to remove “the filth of the National Socialists.”

To Block’s mind, the swastika-imprinted bell wasn’t an integral part of history like the Wittenberg church. “I would make a distinction between the time of racist anti-Semitism and a dictator,” he said, “and an anti-Jewish symbol of the middle ages.”

* * *

Can a medieval relief still be considered a criminal insult today? This is the question the courts have been deliberating in Düllmann’s case. In Germany, defamation on the basis of ethnicity or race is a serious offense. Many of the things Germany would find prosecutable (Holocaust denial, for example) would be permitted under the United States’ exceptionally broad definition of free speech. Germany believes that allowing hate speech endangers the country’s democracy and freedom—a lesson enshrined in its constitution after the Nazi period.

Düllmann had his first opportunity to make his case before a German court in May 2018. He argued that the sculpture should be removed from the church facade. He even suggested that Wittenberg establish a permanent museum to address Christian anti-Semitism. The local court rejected his plea, declaring that the Judensau should remain as a “witness of its times.” Some high-ranking members of the German Lutheran Church disagreed with the decision. Irmgard Schwaetzer, the chair of the church’s nationwide synod, told a reporter that she found Düllmann’s arguments persuasive. The sculpture, she said, “expresses pure hatred of Jews,” and she urged her fellow church members to consider “the feelings that this place awakens in our Jewish brothers and sisters.”

In January 2020, Düllmann made his case again at the appeals court for the state of Saxony-Anhalt in Naumburg. Once again, a panel of judges declined to order the sculpture’s removal. Their reasoning was complex. First, they pointed out, the church wasn’t disputing that the sculpture was offensive. “The parties agree that this relief—at the time of its creation and even in the 16th century, when it was supplemented by the inscription ‘Schem HaMphoras’—served to slander Jews.” The issue, the judges said, was not the intent behind the original sculpture but the way its message comes across today.

In the court’s view, the memorial plaque added to the church grounds in the 1980s, as well as the signage about Martin Luther and the history of medieval anti-Semitism, made all the difference. “You can neutralize the original intent with commentary on the historical context,” the judges wrote. “This is the case with the Wittenberg sculpture.”

The judges summarized Düllmann’s argument in one concise sentence: “An insult remains an insult even if you add commentary around it.” By that logic, they reasoned, every museum exhibit featuring anti-Semitic relics would have to be taken down. Likewise, they continued, Arbeit macht frei, the signage at the Dachau concentration camp, could be seen as comparable to the Judensau sculpture. And yet, because of the new context surrounding it at the restored concentration camp, no one was arguing that this hideous Nazi slogan was offensive today.

The difference, the court acknowledged, was that this particular Judensau could be seen as especially offensive because of its association with Martin Luther himself—the great religious founder glorified in the church and all over Wittenberg. The Dachau site had been preserved only to warn visitors about the crimes of the past, whereas the church was still being used for religious services. But the Mahnmal countered that seeming endorsement, in the judges’ view. There was no way a visitor could assume that the modern-day Lutheran church still held the views expressed in the Judensau.

Of course, there’s always the danger that neo-Nazis could look at the sculpture, ignore the historical context and draw direct inspiration from the debasing image of Jews suckling at a sow’s teats. But that reaction couldn’t be helped, the court concluded, saying the law “does not aim to prevent rioting in the vicinity of the church, or a positive interpretation of the sculpture by neo-Nazis.”

Düllmann and his lawyers plan on continuing their fight. Their next stop is Germany’s equivalent of the Supreme Court—the Federal Constitutional Court in Karlsruhe, a city in southwest Germany. If that fails, Düllmann has one more option: the European Court of Human Rights, based in Strasbourg, France. “Those will be European judges,” he told me. “Maybe they’ll be more impartial.”

* * *

In March 2018, the AfD issued a statement about the Wittenberg Judensau. Anti-Semitism was no longer a German problem, the ultra-nationalist party asserted. Muslim immigrants were the ones bringing the specter of Jew-hatred back to German soil—and Germans were being unfairly expected to pay for that resurgence by removing a medieval relief that the AfD called “priceless” and “irreplaceable.”

“It has over 700 years of history in the city center,” the statement lamented of the Wittenberg sculpture. “Now, if it were up to some theologians, educationalists, and other world observers, it would be put behind glass or, better yet, completely destroyed—700 years of history.”

For those who hold this view, memorials and signs like the ones outside the Wittenberg church come across as denigrating rather than ameliorating. The founding AfD politician Björn Höcke made international headlines in 2017 when he called on Germans to take a “180-degree turn” in their approach to history. Höcke is a state assembly member in Thuringia, a region just south of Saxony-Anhalt where the Brothers Grimm gathered inspiration for their fairy tales and tour guides dress in medieval costumes. At a rally in Dresden, Höcke lamented that “German history is handled as rotten and made to look ridiculous.” He expressed scorn for the Holocaust memorial in Berlin, complaining that Germans were the only people in the world who would erect “a monument of shame” in their nation’s capital. In response, the crowd shouted over and over, “Deutschland! Deutschland!”

In the AfD stronghold of Saxony, another church is struggling with the best way to handle its anti-Semitic past. The parish, in a town called Calbe, had removed for restoration a sculpture of a Jew suckling at a pig’s teat, but then decided to retire it altogether. The issue went to court this past June, where judges ordered them to reinstall the sculpture in its original spot. The parish complied, but instead of adding apologetic memorials or signs, the church has opted to keep the sculpture covered for the foreseeable future. As the mayor of Calbe told the Jewish Telegraph Agency, “I don’t think anyone really wanted to have to see this chimera again.”

There’s a term in the German language—Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung—which roughly translates to “dealing with the past.” One chapter of that past came to a close in 1945, with the fall of the Third Reich. Another ended in 1989, when the Berlin Wall came down and statues of Vladimir Lenin were removed from public spaces in the east. But the towering churches that still stand as architectural gems and religious inspirations raise different kinds of questions.

When the judges delivered their ruling on the Wittenberg Judensau in February, an older man with a white beard sitting in the back of the courtroom stood up and left the room crying. I spoke to him afterward.

Winfried Böhm, a 68-year-old pensioner, said he had spent 22 years serving on the council of his local Lutheran church. He had driven six hours from his home near Lake Constance on the Swiss border to attend this trial. “Our children have been betrayed,” he said through tears. “We say ‘never again,’ but it is here all around us. It is our greatest shame.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ee/5a/ee5ae9a4-a037-4560-bacc-48cb4e8d43ca/mobile_-_oct2020_b06_antisemiticsculptures_copy_2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7d/22/7d223f46-d4d9-4742-89bb-e4de8c69d56f/opener_-_oct2020_b06_antisemiticsculptures.jpg)