Geronimo’s Appeal to Theodore Roosevelt

Held captive far longer than his surrender agreement called for, the Apache warrior made his case directly to the president

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Geronimo-blog-hero-631.jpg)

When he was born he had such a sleepy disposition his parents named him Goyahkla—He Who Yawns. He lived the life of an Apache tribesman in relative quiet for three decades, until he led a trading expedition from the Mogollon Mountains south into Mexico in 1858. He left the Apache camp to do some business in Casa Grandes and returned to find that Mexican soldiers had slaughtered the women and children who had been left behind, including his wife, mother and three small children. “I stood until all had passed, hardly knowing what I would do,” he would recall. “I had no weapon, nor did I hardly wish to fight, neither did I contemplate recovering the bodies of my loved ones, for that was forbidden. I did not pray, nor did I resolve to do anything in particular, for I had no purpose left.”

He returned home and burned his tepee and his family’s possessions. Then he led an assault on a group of Mexicans in Sonora. It would be said that after one of his victims screamed for mercy in the name of Saint Jerome—Jeronimo in Spanish—the Apaches had a new name for Goyahkla. Soon the name provoked fear throughout the West. As immigrants encroached on Native American lands, forcing indigenous people onto reservations, the warrior Geronimo refused to yield.

Born and raised in an area along the Gila River that is now on the Arizona-New Mexico border, Geronimo would spend the next quarter-century attacking and evading both Mexican and U.S. troops, vowing to kill as many white men as he could. He targeted immigrants and their trains, and tormented white settlers in the American West were known to frighten their misbehaving children with the threat that Geronimo would come for them.

By 1874, after white immigrants demanded federal military intervention, the Apaches were forced onto a reservation in Arizona. Geronimo and a band of followers escaped, and U.S. troops tracked him relentlessly across the deserts and mountains of the West. Badly outnumbered and exhausted by a pursuit that had gone on for 3,000 miles—and which included help from Apache scouts—he finally surrendered to General Nelson A. Miles at Skeleton Canyon, Arizona in 1886 and turned over his Winchester rifle and Sheffield Bowie knife. He was “anxious to make the best terms possible,” Miles noted. Geronimo and his “renegades” agreed to a two-year exile and subsequent return to the reservation.

In New York, President Grover Cleveland fretted over the terms. In a telegram to his secretary of war, Cleveland wrote, “I hope nothing will be done with Geronimo which will prevent our treating him as a prisoner of war, if we cannot hang him, which I would much prefer.”

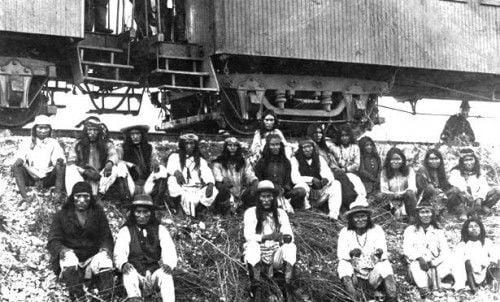

Geronimo avoided execution, but dispute over the terms of surrender ensured that he would spend the rest of his life as a prisoner of the Army, subject to betrayal and indignity. The Apache leader and his men were sent by boxcar, under heavy guard, to Fort Pickens in Pensacola, Florida, where they performed hard labor. In that alien climate, the Washington Post reported, the Apache died “like flies at frost time.” Businessmen there soon had the idea to have Geronimo serve as a tourist attraction, and hundreds of visitors daily were let into the fort to lay eyes on the “bloodthirsty” Indian in his cell.

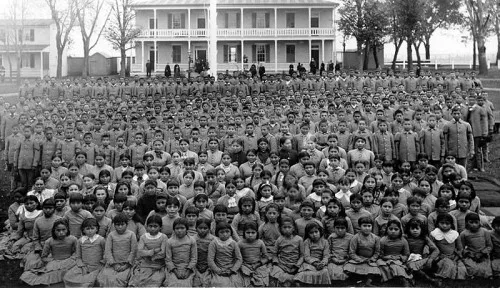

While the POWs were in Florida, the government relocated hundreds of their children from their Arizona reservation to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. More than a third of the students quickly perished from tuberculosis, “died as though smitten with the plague,” the Post reported. Apaches lived in constant terror that more of their children would be taken from them and sent east.

Geronimo and his fellow POWs were reunited with their families in 1888, when the Chiricahua Apaches were moved to Mount Vernon Barracks in Alabama. But there, too, the Apaches began to perish—a quarter of them from tuberculosis— until Geronimo and more than 300 others were brought to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, in 1894. Though still captive, they were allowed to live in villages around the post. In 1904, Geronimo was given permission to appear at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, which included an “Apache Village” exhibit on the midway.

He was presented as a living museum piece in an exhibit intended as a “monument to the progress of civilization.” Under guard, he made bows and arrows while Pueblo women seated beside him pounded corn and made pottery, and he was a popular draw. He sold autographs and posed for pictures with those willing to part with a few dollars for the privilege.

Geronimo seemed to enjoy the fair. Many of the exhibits fascinated him, such as a magic show during which a woman sat in a basket covered in cloth and a man proceeded to plunge the swords through the basket. “I would like to know how she was so quickly healed and why the wounds did not kill her,” Geronimo told one writer. He also saw a “white bear” that seemed to be “as intelligent as a man” and could do whatever his keeper instructed. “I am sure that no grizzly bear could be trained to do these things,” he observed. He took his first ride on a Ferris wheel, where the people below “looked no larger than ants.”

In his dictated memoirs, Geronimo said that he was glad he had gone to the fair, and that white people were “a kind and peaceful people.” He added, “During all the time I was at the fair no one tried to harm me in any way. Had this been among the Mexicans I am sure I should have been compelled to defend myself often.”

After the fair, Pawnee Bill’s Wild West show brokered an agreement with the government to have Geronimo join the show, again under Army guard. The Indians in Pawnee Bill’s show were depicted as “lying, thieving, treacherous, murderous” monsters who had killed hundreds of men, women and children and would think nothing of taking a scalp from any member of the audience, given the chance. Visitors came to see how the “savage” had been “tamed,” and they paid Geronimo to take a button from the coat of the vicious Apache “chief.” Never mind that he had never been a chief and, in fact, bristled when he was referred to as one.

The shows put a good deal of money in his pockets and allowed him to travel, though never without government guards. If Pawnee Bill wanted him to shoot a buffalo from a moving car, or bill him as “the Worst Indian That Ever Lived,” Geronimo was willing to play along. “The Indian,” one magazine noted at the time, “will always be a fascinating object.”

In March 1905, Geronimo was invited to President Theodore Roosevelt’s inaugural parade; he and five real Indian chiefs, who wore full headgear and painted faces, rode horses down Pennsylvania Avenue. The intent, one newspaper stated, was to show Americans “that they have buried the hatchet forever.”

After the parade, Geronimo met with Roosevelt in what the New York Tribune reported was a “pathetic appeal” to allow him to return to Arizona. “Take the ropes from our hands,” Geronimo begged, with tears “running down his bullet-scarred cheeks.” Through an interpreter, Roosevelt told Geronimo that the Indian had a “bad heart.” “You killed many of my people; you burned villages…and were not good Indians.” The president would have to wait a while “and see how you and your people act” on their reservation.

Geronimo gesticulated “wildly” and the meeting was cut short. “The Great Father is very busy,” a staff member told him, ushering Roosevelt away and urging Geronimo to put his concerns in writing. Roosevelt was told that the Apache warrior would be safer on the reservation in Oklahoma than in Arizona: “If he went back there he’d be very likely to find a rope awaiting him, for a great many people in the Territory are spoiling for a chance to kill him.”

Geronimo returned to Fort Sill, where newspapers continued to depict him as a “bloodthirsty Apache chief,” living with the “fierce restlessness of a caged beast.” It had cost Uncle Sam more than a million dollars and hundreds of lives to keep him behind lock and key, the Boston Globe reported. But the Hartford Courant had Geronimo “getting square with the palefaces,” as he was so crafty at poker that he kept the soldiers “broke nearly all the time.” His winnings, the paper noted, were used to help pay the cost of educating Apache children.

Journalists who visited him depicted Geronimo as “crazy,” sometimes chasing sightseers on horseback while drinking to excess. His eighth wife, it was reported, had deserted him, and only a small daughter was watching after him.

In 1903, however, Geronimo converted to Christianity and joined the Dutch Reformed Church—Roosevelt’s church—hoping to please the president and obtain a pardon. “My body is sick and my friends have thrown me away,” Geronimo told church members. “I have been a very wicked man, and my heart is not happy. I see that white people have found a way that makes them good and their hearts happy. I want you to show me that way.” Asked to abandon all Indian “superstitions,” as well as gambling and whiskey, Geronimo agreed and was baptized, but the church would later expel him over his inability to stay away from the card tables.

He thanked Roosevelt (“chief of a great people”) profusely in his memoirs for giving him permission to tell his story, but Geronimo never was permitted to return to his homeland. In February 1909, he was thrown from his horse one night and lay on the cold ground before he was discovered after daybreak. He died of pneumonia on February 17.

The Chicago Daily Tribune ran the headline, “Geronimo Now a Good Indian,” alluding to a quote widely and mistakenly attributed to General Philip Sheridan. Roosevelt himself would sum up his feelings this way: “I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are dead Indians, but I believe nine out of ten are, and I shouldn’t like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth.”

After a Christian service and a large funeral procession made up of both whites and Native Americans, Geronimo was buried at Fort Sill. Only then did he cease to be a prisoner of the United States.

Sources

Articles: “Geronimo Getting Square With the Palefaces,” The Hartford Courant, June 6, 1900.” “Geronimo Has Cost Uncle Sam $1,000,000,” Boston Daily Globe, April 25, 1900. “Geronimo Has Gone Mad,” New York Times, July 25, 1900. “Geronimo in Prayer,” The Washington Post, November 29. 1903. “Geronimo Seems Crazy,” New York Tribune, May 19, 1907. “Geronimo at the World’s Fair,” Scientific American Supplement, August 27, 1904. “Prisoner 18 Years,” Boston Daily Globe, September 18, 1904. “Chiefs in the Parade,” Washington Post, February 3, 1905. “Indians at White House,” New York Tribune, March 10, 1905. “Savage Indian Chiefs,” The Washington Post, March 5, 1905. “Indians on the Inaugural March,” by Jesse Rhodes, Smithsonian, January 14, 2009. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/specialsections/heritage/Indians-on-the-Inaugural-March.html “Geronimo Wants His Freedom,” Boston Daily Globe, January 28, 1906. “Geronimo Joins the Church, Hoping to Please Roosevelt,” The Atlanta Constitution, July 10, 1907. “A Bad Indian,” The Washington Post, August 24, 1907. “Geronimo Now Good Indian,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 18, 1909. “Chief Geronimo Buried,” New York Times, February 19, 1909. “Chief Geronimo Dead,” New York Tribune, February 19, 1909. “Native America Prisoners of War: Chircahua Apaches 1886-1914, The Museum of the American Indian, http://www.chiricahua-apache.com/ “’A Very Kind and Peaceful People’: Geronimo and the World’s Fair,” by Mark Sample, May 3, 2011, http://www.samplereality.com/2011/05/03/a-very-kind-and-peaceful-people-geronimo-and-the-worlds-fair/ “Geronimo: Finding Peace,” by Alan MacIver, Vision.org, http://www.vision.org/visionmedia/article.aspx?id=12778

Books: Geronimo, Geronimo’s Story of His Life, Taken Down and Edited by S. M. Barrett, Superintendent of Education, Lawton, Oklahoma, Duffield & Company, 1915.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)