William Laws Calley Jr. was never really meant to be an officer in the U.S. Army. After getting low grades and dropping out of Palm Beach Junior College, he tried to enlist in 1964, but was rejected because of a hearing defect. Two years later, with the escalation in Vietnam, standards for enrollees changed and Calley—neither a valedictorian nor a troublemaker, just a fairly typical American young man trying to figure out what to do with his life—was called up.

Before the decade was over Second Lieutenant Calley would become one of the most controversial figures in the country, if not the world. On March 16, 1968, during a roughly four-hour operation in the Vietnamese village of Son My, American soldiers killed approximately 504 civilians, including pregnant women and infants, gang-raped women and burned a village to ashes. Calley, though a low-ranking officer in Charlie Company, stood out because of the sheer number of civilians he was accused of killing and ordering killed.

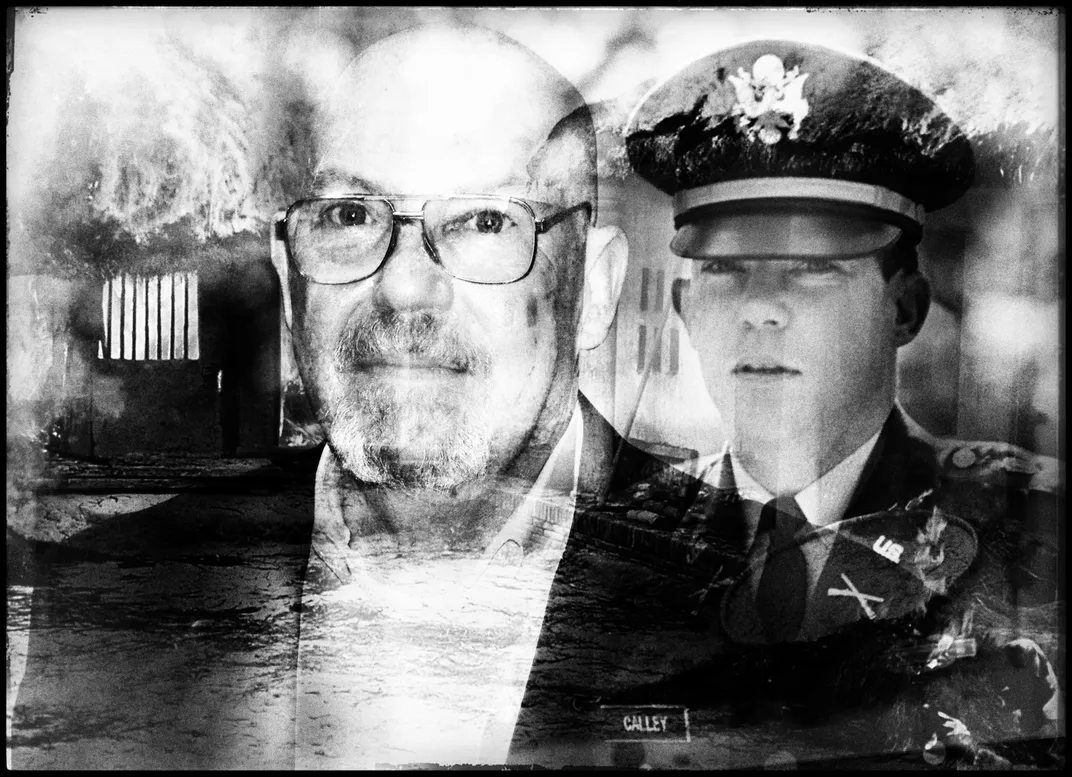

The red-haired Miami native known to friends as Rusty became the face of the massacre, which was named after one of the sub-hamlets where the killings took place, My Lai 4. His story dominated headlines, along with the Apollo 12 moon landing and the trial of Charles Manson. His case became a kind of litmus test for American values, a question not only of who was to blame for My Lai, but how America should conduct war and what constitutes a war crime. Out of the roughly 200 soldiers who were dropped into the village that day, 24 were later charged with criminal offenses, and only one was convicted, Calley. He was set free after serving less than four years.

Since that time, Calley has almost entirely avoided the press. Now 74 years old, he declined to be interviewed for this story. But I was able to piece together a picture of his life and legacy by reviewing court records and interviewing his fellow soldiers and close friends. I traveled to Son My, where survivors are still waiting for him to come back and make amends. And I visited Columbus, Georgia, where Calley lived for nearly 30 years. I wanted to know whether Calley, a convicted mass murderer and one of the most notorious figures in 20th-century history, had ever expressed true contrition or lived a normal life.

**********

The landscape surrounding Son My is still covered with rice paddies, as it was 50 years ago. There are still water buffalo fertilizing the fields and chickens roaming. Most of the roads are still dirt. On a recent Wednesday afternoon, ten young men were drinking beer and smoking cigarettes at the side of one of those roads. A karaoke machine was set up on a motorbike, and the loudspeakers were placed next to a blink-and-you-miss-it plaque with an arrow pointing to a “Mass Grave of 75 Victims.”

Tran Nam was 6 years old when he heard gunshots from inside his mud and straw home in Son My. It was early morning and he was having breakfast with his extended family, 14 people in all. The U.S. Army had come to the village a couple of times previously during the war. Nam’s family thought it would be like before; they’d be gathered and interviewed and then let go. So the family kept on eating. “Then a U.S. soldier stepped in,” Nam told me. “And he aimed into our meal and shot. People collapsed one by one.”

Nam saw the bullet-ridden bodies of his family falling—his grandfather, his parents, his older brother, his younger brother, his aunt and cousins. He ran into a dimly lit bedroom and hid under the bed. He heard more soldiers enter the house, and then more gunshots. He stayed under the bed as long as he could, but that wasn’t long because the Americans set the house on fire. When the heat grew unbearable, Nam ran out the door and hid in a ditch as his village burned. Of the 14 people at breakfast that morning, 13 were shot and 11 killed. Only Nam made it out physically unscathed.

The six U.S. Army platoons that swept through Son My that day included 100 men from Charlie Company and 100 from Bravo Company. They killed some civilians straight off—shooting them point blank or tossing grenades into their homes. In the words of Varnado Simpson, a member of Second Platoon who was interviewed for the book Four Hours in My Lai, “I cut their throats, cut off their hands, cut out their tongue, their hair, scalped them. I did it. A lot of people were doing it, and I just followed. I lost all sense of direction.” Simpson went on to commit suicide.

Soldiers gathered together villagers along a trail going through the village and also along an irrigation ditch to the east. Calley and 21-year-old Pvt. First Class Paul Meadlo mowed the people down with M-16s, burning through several clips in the process. The soldiers killed as many as 200 people in those two areas of Son My, including 79 children. Witnesses said Calley also shot a praying Buddhist monk and a young Vietnamese woman with her hands up. When he saw a 2-year-old boy who had crawled out of the ditch, Calley threw the child back in and shot him.

Truong Thi Le, then a rice farmer, told me she was hiding in her home with her 6-year-old son and 17-year-old daughter when the Americans found them and dragged them out. When the soldiers fired an M-16 into their group, most died then and there. Le fell on top of her son and two bodies fell on top of her. Hours later, they emerged from the pile alive. “When I noticed that it was quiet, I pushed the dead bodies above me aside,” she told me. “Blood was all over my head, my clothes.” She dragged her son to the edge of a field and covered him with rice and cloth. “I told him not to cry or they would come to kill us.”

When I asked about her daughter, Le, who had maintained her composure up till that point, covered her face with her hands and broke down in tears. She told me that Thu was killed along with 104 people at the trail but didn’t die right away. When it was safe to move, Le found Thu sitting and holding her grandmother, who was already dead. “Mom, I’m bleeding a lot,” Le remembers her daughter saying. “I have to leave you.”

Nguyen Hong Man, 13 at the time of the massacre, told me he went into an underground tunnel with his 5-year-old niece to hide, only to watch her get shot right in front of him. “I lay there, horrified,” he said. “Blood from the nearby bodies splashed onto my body. People who were covered with a lot of blood and stayed still got the chance to survive, while kids did not. Many of them died as they cried for their parents in terror.”

Initially, the U.S. Army portrayed the massacre as a great victory over Viet Cong forces, and that story might never have been challenged had it not been for a helicopter gunner named Ronald Ridenhour. He wasn’t there himself, but a few weeks after the operation, his friends from Charlie Company told him about the mass killing of civilians. He did some investigating on his own and then waited until he finished his service. Just over a year after the massacre, Ridenhour sent a letter to about two dozen members of Congress, the secretaries of state and defense, the secretary of the Army, and the chairman of the Joints Chiefs of Staff, telling them about a “2nd Lieutenant Kally” who had machine-gunned groups of unarmed civilians.

Ridenhour’s letter spurred the inspector general of the Army, Gen. William Enemark, to launch a fact-finding mission, led by Col. William Wilson. At a hotel in Terre Haute, Indiana, Wilson spoke to Meadlo, the soldier who with Calley had gunned down the rows of villagers. Meadlo had been discharged from the Army because of a severe injury; like many others who’d been at Son My, he was essentially granted immunity when the investigation began. As he described what he’d done and witnessed, he looked at the ceiling and wept. “We just started wiping out the whole village,” he told Wilson.

A subsequent inquiry by the Army’s Criminal Investigation Command discovered that military photographer Ronald Haeberle had taken photos during the operation. In a hotel room in Ohio, before a stunned investigator, Haeberle projected on a hung-up bedsheet horrifying images of piled dead bodies and frightened Vietnamese villagers.

Armed with Haeberle’s photos and 1,000 pages of testimony from 36 witnesses, the Army officially charged Calley with premeditated murder—just one day before he was scheduled to be discharged. Eighteen months later, in March 1971, a court-martial with a jury of six fellow officers, including five who had served in Vietnam, found Calley guilty of murdering at least 22 civilians and sentenced him to life in prison.

The day the verdict came down, Calley defended his actions in a statement to the court: “My troops were getting massacred and mauled by an enemy I couldn’t see, I couldn’t feel and I couldn’t touch—that nobody in the military system ever described them as anything other than Communism. They didn’t give it a race, they didn’t give it a sex, they didn’t give it an age. They never let me believe it was just a philosophy in a man’s mind. That was my enemy out there.”

**********

Despite the overwhelming evidence that Calley had personally killed numerous civilians, a survey found that nearly four out of five Americans disagreed with his guilty verdict. His name became a rallying cry on both the right and the left. Hawks said Calley had been simply doing his job. Doves said Calley had taken the fall for the generals and politicians who’d dragged America into a disastrous and immoral conflict. In newspaper articles around the world, one word became entwined with Calley’s name: scapegoat.

Within three months of the verdict, the White House received more than 300,000 letters and telegrams, almost all in support of the convicted soldier. Calley himself received 10,000 letters and packages a day. His military defense counsel, Maj. Kenneth Raby, who spent 19 months working on the court-martial, told me Calley received so much mail that he had to be moved to a ground-floor apartment at Fort Benning where the deliveries didn’t have to be carried up the stairs.

Some of Calley’s supporters went to great lengths. Two musicians from Muscle Shoals, Alabama, released a recording called “The Battle Hymn of Lt. Calley,” which included the line, “There’s no other way to wage a war.” It sold more than a million copies. Digger O’Dell, a professional showman based in Columbus, Georgia, buried himself alive for 79 days in a used-car lot. Passersby could drop a coin into a tube that led down to O’Dell’s “grave,” with the proceeds going toward a fund for Calley. He later welded shut the doors of his car, refusing to come out until Calley was set free.

Politicians, noting the anger of their constituents, made gestures of their own. Indiana Gov. Edgar Whitcomb ordered the state’s flags to fly at half-staff. Gov. John Bell Williams of Mississippi said his state was “about ready to secede from the Union” over the Calley verdict. Gov. Jimmy Carter, the future president, urged his fellow Georgians to “honor the flag as Rusty had done.” Local leaders across the country demanded that President Nixon pardon Calley.

Nixon fell short of a pardon, but he ordered that Calley remain under house arrest in his apartment at Fort Benning, where he could play badminton in the backyard and hang out with his girlfriend. After a series of appeals, Calley’s sentence was cut from life to 20 years, then in half to ten years. He was set free in November 1974 after serving three and a half years, most of it at his apartment. In the months after his release, Calley made a few public appearances, and then moved a 20-minute drive down the road to Columbus, Georgia, where he disappeared into private life.

**********

Situated along the Chattahoochee River, Columbus is first and foremost a military town. Its residents’ lives are linked to Fort Benning, which has served as the home of the U.S. Infantry School since 1918 and today supports more than 100,000 civilian and military personnel. “The Army is just a part of day-to-day life here,” the longtime Columbus journalist Richard Hyatt told me. “And back in the day, William Calley was part of that life.”

Bob Poydasheff, the former mayor of Columbus, says there was controversy when Calley moved to town. “There were many of us who were just horrified,” he told me, raising his voice until he was almost shouting. “It’s just not done! You don’t go and kill unarmed civilians!”

Still, Calley became a familiar face around Columbus. In 1976, he married Penny Vick, whose family owned a jewelry shop frequented by members of Columbus’ elite. One of their wedding guests was U.S. District Judge J. Robert Elliott, who had tried to get Calley’s conviction overturned two years earlier.

After the wedding, Calley began working at the jewelry shop. He took classes to improve his knowledge of gemstones and got trained to make appraisals to increase the store’s business. In the 1980s, he applied for a real estate license and was initially denied because of his criminal record. He asked Reid Kennedy, the judge who had presided over his court-martial, if he’d write him a letter. He did so, and Calley got the license while continuing to work at the shop. “It’s funny isn’t it, that a man who breaks into your house and steals your TV will never get a license, but a man who’s convicted of killing 22 people can get one,” Kennedy told the Columbus Ledger-Enquirer in 1988.

Al Fleming, a former local TV news anchor, described Calley as a soft-spoken man. When I met Fleming in Columbus over a steak dinner, one of the first things he told me was, “I’m not going to say anything bad about Rusty Calley....He and I were the best of friends for a long time. We still are, as far as I’m concerned.” (Calley left town some years back and now lives in Gainesville, Florida.) Fleming described how Calley used to sit with him at the restaurant he owned, Fleming’s Prime Time Grill, and talk late into the night about Vietnam. He told Fleming that Charlie Company had been sent to My Lai to “scorch the earth,” and that even years after his conviction, he still felt he’d done what he’d been ordered to do.

After our dinner, Fleming gave me a tour in his tiny red Fiat, pausing to point out the house where Calley lived for nearly 30 years. He also pointed out an estate nearby that had appeared in The Green Berets, a pro-war 1968 film starring John Wayne. The Army had participated heavily in the production, providing uniforms, helicopters and other equipment. The battle scenes were filmed at Fort Benning, and a house in Columbus was used as a stand-in for a Viet Cong general’s villa. In the 1980s, the Green Beret house caught fire. When the neighbors rushed out to form a bucket brigade, Calley was right there with everyone else, trying to put out the flames.

During his time in Columbus, Calley mostly succeeded in keeping himself out of the national spotlight. (Hyatt, the journalist, used to go to V.V. Vick Jewelers every few years, on the anniversary of the massacre, to try to get an interview with Calley, but was always politely denied.) Calley and Penny had one son, William Laws Calley III, known as Laws, who went on to get a PhD in electrical engineering at Georgia Tech. But divorce documents I found at the Muscogee County clerk’s office present a dismal picture.

According to a legal brief filed by Calley’s attorney in 2008, he spent most of his adult years feeling powerless both at work and at home. It states that Calley did all the cooking, and all the cleaning that wasn’t done by the maid, and that he was their son’s primary caretaker. The jewelry store, according to the document, “was his life and, except for his son, was where he derived his self-worth....He even worked hard to try to infuse new ideas into the store to help it grow and be more profitable, all of which were rejected by Mrs. Calley.” In 2004, his wife, who inherited the store from her parents, stopped paying him a salary. He fell into a depression and moved to Atlanta to stay with Laws, living off his savings until it was gone. Calley and his son remain close.

The divorce documents provided little information about Penny Vick’s side of the story apart from two ambiguous details. (Vick and Laws also declined to be interviewed for this story.) His lawyer disputed one assertion—that Calley “had been backing away from his marital relationship” prior to separation—but confirmed the other assertion—that Calley “consumed alcoholic beverages in his own area of the home on a daily basis.”

In a strange twist, John Partin, the lawyer who represented Calley’s wife in the divorce, was a former Army captain who had served as an assistant prosecutor in Calley’s court-martial. “I’m proud of what we did,” Partin told me, referring to the nearly two years he spent trying to put Calley in prison. He and his co-counsel called about 100 witnesses to testify against Calley. When Nixon intervened to keep Calley out of jail, Partin wrote a letter to the White House saying that the special treatment accorded a convicted murderer had “defiled” and “degraded” the military justice system.

By the time the divorce was settled, according to the court documents, Calley was suffering from prostate cancer and gastrointestinal problems. His lawyer described his earning capacity as “zero based upon his age and health.” He asked Penny for a lump alimony sum of $200,000, half of their home equity, half of the individual retirement account in Penny’s name, two baker’s shelves and a cracked porcelain bird that apparently held emotional significance.

**********

The closest Calley ever came to publicly apologizing for My Lai was at a 2009 meeting of the Kiwanis Club of Greater Columbus. Fleming set up the talk, on a Wednesday afternoon. No reporters were invited, but a retired local newsman surreptitiously blogged about it online and the local paper picked up the story. “There is not a day that goes by that I do not feel remorse for what happened that day in My Lai,” Calley told the 50 or so Kiwanis members. “I feel remorse for the Vietnamese who were killed, for their families, for the American soldiers involved and their families. I am very sorry.”

The historian Howard Jones, author of My Lai: Vietnam, 1968, and the Descent into Darkness, read Calley’s words in news reports but didn’t believe they showed true contrition. “There just was no inner change of heart,” Jones told me. “I mean it just wasn’t there. No matter how people tried to paint it.” Jones especially took issue with the fact that Calley insisted in the Kiwanis speech that he’d only been following orders.

It’s still unclear exactly what Capt. Ernest L. Medina told the men of Charlie Company the night before they were helicoptered into Son My. (He did not respond to interview requests for this story.) The captain reportedly told his soldiers that they were finally going to meet the Viet Cong’s 48th Local Force Battalion, a well-armed division of at least 250 soldiers, which for months had tormented them. Medina later claimed that he’d never told his men to kill innocent civilians. He testified at Calley’s court-martial that Calley had “hemmed and hawed” before admitting the extent of the slaughter. He said Calley told him, two days after the massacre, “I can still hear them screaming.” Medina himself was charged, tried and found innocent.

My Lai: Vietnam, 1968, and the Descent into Darkness (Pivotal Moments in American History)

Compelling, comprehensive, and haunting, based on both exhaustive archival research and extensive interviews, Howard Jones's My Lai will stand as the definitive book on one of the most devastating events in American military history.

I wanted to get firsthand reports from other Charlie Company men who were at Son My, so I started making calls and writing letters. I eventually reached five former soldiers willing to speak on the record. Dennis Bunning, a former private first class in Second Platoon who now lives in California, remembered Medina’s pep talk this way: “We’re going to get even with them for all the losses we’ve had. We’re going in there, we’re killing everything that’s alive. We’re throwing the bodies down the wells, we’re burning the villages, and we’re wiping them off of the map.”

It would have been a compelling message for young men who had spent the previous months getting attacked by invisible forces. They had lost friends to booby traps, land mines and sniper fire. By March 16, Charlie Company alone had suffered 28 casualties, five dead and many others permanently maimed, without once engaging directly with an enemy combatant.

“Most of everything that was going on was insanity in my view. It was trying to survive,” said Lawrence La Croix of Utah, who was only 18 when he went into Son My as a Second Platoon squad leader. “The problem is, when you step on a mine or a booby trap there’s nothing to take your anger out on. It’s not like a firefight where you get to shoot back. You can’t shoot a mine. It doesn’t really care.”

“All your friends are getting killed and there is nobody to fight,” echoed John Smail, Third Platoon squad leader, now living in Washington State. “So when we thought we had a chance to meet them head-on, we were pumped.”

Kenneth Hodges, a former sergeant, who is now living in rural Georgia, told me he was devastated when he heard of Calley’s partial apology at the Columbus Kiwanis Club. “I felt like crying, really, because he had nothing to apologize for,” said Hodges. “I know today I don’t have anything to apologize for. I went to Vietnam and I served two tours and I served honorably. On that particular operation, I carried out the order as it was issued. A good soldier receives, obeys and carries out the orders that he is issued, and he reports back. That’s the way it was in ’68. That’s the way I was trained.”

In contrast, Meadlo expressed intense remorse. He is living in Indiana, and he says that as he gets older the memories of My Lai come back more frequently, not less. “When I’m sleeping, I can actually see the faces, and that’s the honest-to-God truth,” he told me. “I can actually see the faces and the terror and all those people’s eyes. And I wake up and I’m just shaking and I just can’t hardly cope with it. The nightmares and everything will never go away. I’m sure of that. But I have to live with it.”

Meadlo stood 10 to 15 feet away from a group of villagers and went through at least four clips of 17 bullets each. He almost certainly killed relatives of the people I spoke with in Vietnam. It might have been Meadlo’s bullets that struck Truong Thi Le’s daughter or his Zippo that burned Tran Nam’s home.

The day after the massacre, Meadlo stepped on a land mine and his right foot was blown off. As he was whisked away on a helicopter, Meadlo reportedly shouted, “Why did you do it? This is God’s punishment to me, Calley, but you’ll get yours! God will punish you, Calley!”

Meadlo is still angry at the U.S. government for sending him to Vietnam in the first place, but he says he no longer holds a grudge against Calley. “I think he believed that he was doing his duty and doing his job when he was over there,” he told me. “He might have got sidetracked.”

**********

Tran Nam, the Son My villager who hid under a bed as a 6-year-old while his family fell around him, is now 56 years old. He works as a gardener at the Son My Vestige Site, a small museum dedicated to the memory of all those killed in 1968. The garden contains the brick bases of 18 out of the 247 homes that were otherwise destroyed that day. In front of each is a plaque with the name of the family that lived there and a list of the members of that family who were killed.

Inside the museum, items that once belonged to the people of Son My sit in glass cases: the rosary beads and Buddhist prayer book of the 65-year-old monk Do Ngo, the round-bellied fish sauce pot of 40-year-old Nguyen Thi Chac, the iron sickle of 29-year-old Phung Thi Muong, a single slipper of 6-year-old Truong Thi Khai and the stone marbles of two young brothers. One case displays a hairpin that belonged to 15-year-old Nguyen Thi Huynh; her boyfriend held onto it for eight years after the massacre before donating it to the museum.

At the museum’s entrance is a large black marble plaque that bears the names and ages of every person killed in Son My on March 16, 1968. The list includes 17 pregnant women and 210 children under the age of 13. Turn left and there is a diorama of how the village looked before every dwelling was burned down. The walls are lined with Ronald Haeberle’s graphic photos, as well as pictures of Calley and other soldiers known to have committed atrocities, including Meadlo and Hodges. American heroes are celebrated, like Ronald Ridenhour, the ex-G.I. who first exposed the killings (he died in 1998), and Hugh Thompson, a pilot, and Lawrence Colburn, a gunner, who saved nine or ten civilians the day of the massacre by airlifting them on their helicopter (both Thompson and Colburn later died of cancer). There are also photos of former U.S. soldiers who have visited the museum, including a Vietnam veteran named Billy Kelly who has 504 roses delivered to the museum on the anniversary of the massacre every year. Sometimes he brings them personally.

The director of the museum, Pham Thanh Cong, is a survivor himself. He was 11 years old when he and his family heard the Americans shooting and hid in a tunnel underneath their home. As the soldiers approached, Cong’s mother told him and his four siblings to move deeper inside. A member of the U.S. Army then threw a grenade into the tunnel, killing everyone except Cong, who was injured by the shrapnel and still bears a scar next to his left eye.

When we sat down, Cong thanked me for coming to the museum, for “sharing the pain of our people.” He told me it had been a complete surprise when the troops entered the village. “No one fought back,” he said. “After four hours, they killed the entire village and withdrew, leaving our village full of blood and fire.” Cong’s full-time job is to make sure the massacre is not forgotten.

For Americans, My Lai was supposed to be a never-again moment. In 1969, the antiwar movement turned one of Haeberle’s photographs of dead women and children into a poster, overlaid with a short, chilling quote from Meadlo: “And babies.” It was largely because of My Lai that returning Vietnam veterans were widely derided as “baby killers.”

Even decades later, military personnel used the massacre as a cautionary tale, a reminder of what can happen when young soldiers unleash their rage on civilians. “No My Lais in this division—do you hear me?” Maj. Gen. Ronald Griffith told his brigade commanders before entering battle in the Persian Gulf War.

Yet Cong and the other survivors are painfully aware that all the soldiers involved in the massacre went free. The only one to be convicted was released after a brief and comfortable captivity. I asked Cong whether he would welcome a visit from Calley. “For Vietnamese people, when a person knows his sin, he or she must repent, pray and acknowledge it in front of the spirits,” Cong told me. “Then he will be forgiven and his mind will be relaxed.” Indeed, the home of every survivor I interviewed had an altar in the living room, where incense was burned and offerings were made to help the living venerate dead family members.

It seems unlikely that Calley will make that trip. (Smithsonian offered him the opportunity to accompany me to Vietnam and he declined.) “If Mr. Calley does not return to Vietnam to repent and apologize to the 504 spirits who were killed,” Cong told me, “he will always be haunted, constantly obsessed until he dies, and even when he dies, he won’t be at peace. So I hope he will come to Vietnam. These 504 spirits will forgive his sins, his ignorant mind that caused their death.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(1515x2109:1516x2110)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/38/b4/38b40886-d252-4d10-9a1b-bb566b73a195/1_1017_ajs_my_lai_vietnam-1320_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/38/b4/38b40886-d252-4d10-9a1b-bb566b73a195/1_1017_ajs_my_lai_vietnam-1320_copy.jpg)