Through the window of a small plane, I look out over the vastness of the Yukon Territory—an area bigger than California with only 33,000 residents. It’s an austere landscape of glaciated mountain ranges, frozen lakes, ice fields and spruce forests. Then the mountains are behind us, and there are low hills and tundra to the horizons, and a big frozen river starting to melt.

It was this stark wilderness that 100,000 prospectors tried to cross on foot, and in homemade boats, during the Klondike gold rush of the 1890s. The “stampeders,” as they were known, were desperate to reach the gold fields around Dawson City, but the journey took more than two months, and was so punishing and dangerous that only 30,000 made it through. In the first wave was a tough, stocky 21-year-old from San Francisco named Jack London.

Questing for gold, what he found instead was inspiration and material for one of the most successful literary careers of all time. His best-known Yukon book, The Call of the Wild, has been translated into nearly 100 languages, and will be released in February as a movie starring Harrison Ford as a Klondike gold prospector. Such is the enduring power of the story—a dog named Buck is kidnapped from California and thrust into the frozen wilds of the Far North—that this is the ninth time that the 1903 novel has been adapted for film or television.

Techniques including computer-generated imagery enabled the latest filmmakers to shoot the entire production without leaving California, and it’s hard to criticize them for not using authentic Yukon locations. In summertime, the advantages of 20-hour daylight are offset by horrendous swarms of mosquitoes, among other challenges. In mid-winter, when much of the story takes place, the sun doesn’t reach the horizon and temperatures plunge to 50, 60, or even 70 degrees below zero Fahrenheit. In that kind of weather, as Jack London discovered, even the strongest whiskey freezes solid, and a man’s spit turns to ice before it hits the snow.

The best story that Jack London never wrote, at least not in full, was a factual account of his time in the Far North. But it can be pieced together from letters and diary entries, a handful of nonfiction articles that he sold to magazines, the remembrances of other people, and guesswork from his fiction. And you can still see his cabin and his old stomping grounds in Dawson City, the former capital of the Klondike gold rush, where my plane lands with a crunch on an unpaved runway.

* * *

Because he was only 21, it’s easy to assume that Jack London was innocent and naive when he set out for the Far North. But that wasn’t the case. He grew up poor in a broken home, and at age 15, he joined a gang of prison-hardened oyster pirates who risked their lives in small boats at night, trying to outwit the armed guards who watched over the oyster beds in San Francisco Bay. Jack soon became an expert sailor, and an accomplished drinker and brawler in the waterfront saloons. At 17, he sailed across the Pacific and up to the Bering Sea on a seal-hunting ship. He also worked 16-hour days in a Dickensian canning factory in Oakland, hoboed from coast to coast on freight trains, learned to beg and steal, spent 30 days for vagrancy in a vicious New York jail, and became a confirmed socialist—all by the age of 19.

In July 1897, he had just quit a job in a laundry when the steamship Portland docked in Seattle and the Excelsior in San Francisco. Miners came down the gangplanks hefting three tons of gold from far northwest Canada. Newspapers and telephones spread the word almost instantly, and sparked one of the biggest, wildest, most delusional gold rushes in history. Experienced miners and prospectors were joined by great hordes of factory workers, store clerks, salesmen, bureaucrats, police officers and other city dwellers, most of them completely inexperienced in the wilderness and clueless about the Far North.

Jack was desperate to join them, but he couldn’t raise the money for passage or supplies. Fortunately, his 60-year-old brother-in-law James “Cap” Shepard also became infected with the “Klondicitis,” as the gold fever was known. Shepard mortgaged his wife’s home to finance the trip, and invited Jack along because of the young man’s muscle and skill at roughing it. They bought fur-lined coats and caps, high heavy boots, thick mittens, tents, blankets, axes, mining gear, a metal cookstove, tools to build boats and cabins, and a year’s supply of food. Jack, a voracious reader with little schooling and vague ambitions to become a writer, threw in volumes of Milton and Darwin and a few other books.

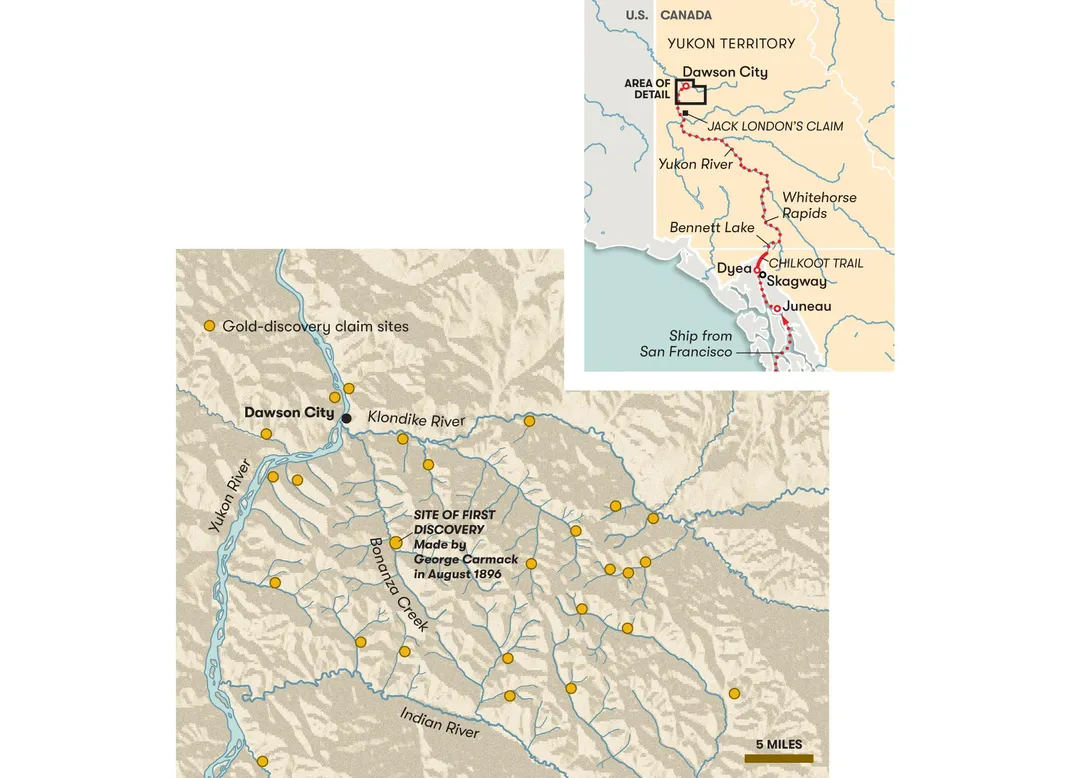

They sailed away to Alaska on a ship packed with gold-seekers and partnered with three of them: “Big Jim” Goodman, an experienced miner and hunter; Ira Sloper, a gritty carpenter and adventurer who weighed barely 100 pounds; and a red-whiskered court reporter, Fred C. Thompson, who kept a terse, deadpan diary of the trip. Disembarking at Juneau, they hired Tlingit canoes and paddled up a 100-mile fjord to Dyea, where the infamous Chilkoot Trail began.

To reach the Klondike, they first needed to get themselves and all their supplies over the Alaskan coastal range, on a trail too steep for horses or pack mules. They sent 3,000 pounds of supplies to the summit with Tlingit packers, at 22 cents per pound, and carried the rest on their backs. Several sources state that Jack hauled about a ton, which was average. A strong man who could backpack 100 pounds had to make 20 round trips, walking a total of 40 miles, in order to move that burden one mile.

The going was rough and muddy, with patches of quagmire. They had to cross and recross a raging river on felled trees. “They are very hard to walk on, with water rushing underneath and one hundred pounds on your back,” Thompson noted in his diary. Men who fell were usually drowned by the weight of their packs; they were buried in shallow graves beside the trail. Nine miles out from Dyea, Cap Shepard was in so much pain from his rheumatism that he said goodbye to the other men and turned back down the trail.

The others pressed on through heavy rain and deepening mud. They picked up an elderly gold-seeker named Martin Tarwater, who offered to cook for them. Jack later fictionalized him, keeping the name Tarwater, in a short story, “Like Argus of the Ancient Times.” On August 21, with blistered feet and raw shoulders, they reached Sheep Camp, which Thompson described as “a very tough hole.” More than 1,000 stampeders crowded together in a muddy tent city. It was the last piece of level ground before the dreaded ascent to Chilkoot Pass.

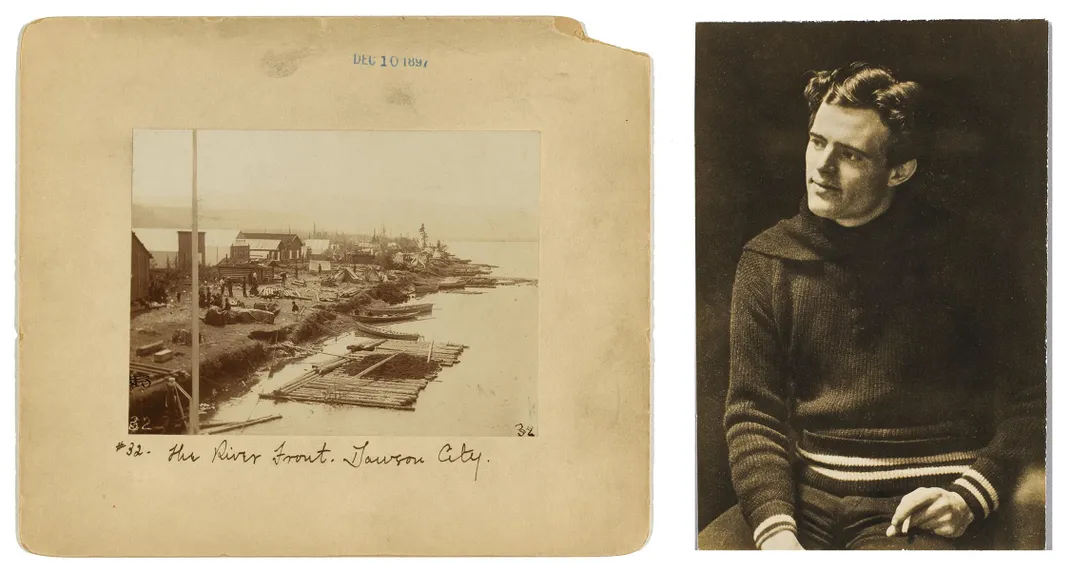

A photographer, Frank LaRoche, was there documenting the gold rush for the U.S. Geological Survey. He gathered up 24 men and photographed them standing in the mud with a glacier in the background. They all look stern and solemn, including young Jack London with a tousled forelock protruding from his cap and a hand shoved into his pocket. It’s the only known photograph of him in the Far North.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5a/c9/5ac96271-0357-4c65-9276-880f13873650/1nov2019_a17_jacklondon.jpg)

A better known photograph shows a long line of heavily laden men climbing up a brutally steep slope to Chilkoot Pass—“like a column of ants,” Jack later described them. It’s an astonishing image of men pushed to extremes. Yet it fails to convey a key fact: Most of the men had to climb that terrible slope 20 or 30 times. The pass marked the boundary between Alaska, an American possession, and the Yukon Territory. Canadian authorities required each individual to bring enough food to last a year, or about 1,000 pounds. And that load doubled with mining and camping gear.

Many men looked up at the steepness of the trail, calculated how many trips it would take and turned back toward Dyea, dumping the detestable burden of their supplies. Many tried to make the climb, but lacked the strength and stamina. They collapsed in despair or grimacing in pain from back injuries. At least 70 were killed by landslides and avalanches. No one who lived through the Chilkoot ever forgot it, least of all Jack London, who wrote about it with great vividness in several fictional accounts.

The elation of reaching the top of the pass for the last time did not last long; now the men had to backpack all their supplies another 16 miles, then cut down trees and build a boat, cross a series of lakes, portage the boat and supplies between the lakes, then travel 500 miles north on the Yukon River—and do it all before the river froze. It was already snowing in mid-September. Ice was forming on the lakeshores. Racing winter, they rationed themselves to five hours of sleep a night.

In a boat built from spruce by Sloper the carpenter, with a mast and sail rigged by Jack London the sailor, they made it over the lakes in gales and blizzards, and saw two other boats capsize and drown everyone aboard.

On September 24, they entered a tributary of the Yukon River called Sixtymile. The following day at Box Canyon, the river narrowed into a roaring, foaming chute and they faced a tough decision. So many boats had wrecked in the rapids that most stampeders were now portaging their boats and supplies around them, but that took four days. Jack’s group voted to run the rapids.

The 27-foot boat was heavily laden with supplies. There were hundreds of spectators on the canyon walls, predicting disaster. Jack steered with a sweep-oar as they careened through the white water, and the others paddled frantically to avoid getting dashed against the rocks. The current was so swift that they ran the mile-long canyon in two minutes, with no damage done except one snapped paddle.

An even bigger challenge came at White Horse Rapids, which featured big standing waves, jagged rocks and whirlpools. Again, Jack’s boatmanship got them through. Then, with admirable generosity, he went back and helped a young couple run their skiff through the same rapids. Thompson wrote in his diary that they rested easy that night.

Sixtymile River flowed into 30-mile Lake Laberge. It took a week to battle across it in howling north winds and snowstorms. The going was easier below Laberge, although the weather was bitterly cold with dense fogs. The big worry was the ice accumulating in the river.

The Yukon—the third-biggest river in North America, after the Mississippi and the Mackenzie—usually froze solid by mid-October. On October 9, about 80 miles from Dawson City, they decided to stop and winter at the mouth of the Stewart River, where they found some old serviceable cabins and Big Jim saw promising color in his gold pan. Jack staked out 500 feet on the left fork of Henderson Creek and boated downriver to file his mining claim in Dawson City.

Founded the previous year, Dawson now had more than a dozen saloons with dance halls and gambling, a street of prostitutes called Paradise Alley and some 5,000 inhabitants living in cabins, tents and shanties. There was a food shortage, no sanitation, and the filthy streets were full of unemployed men and sled dogs.

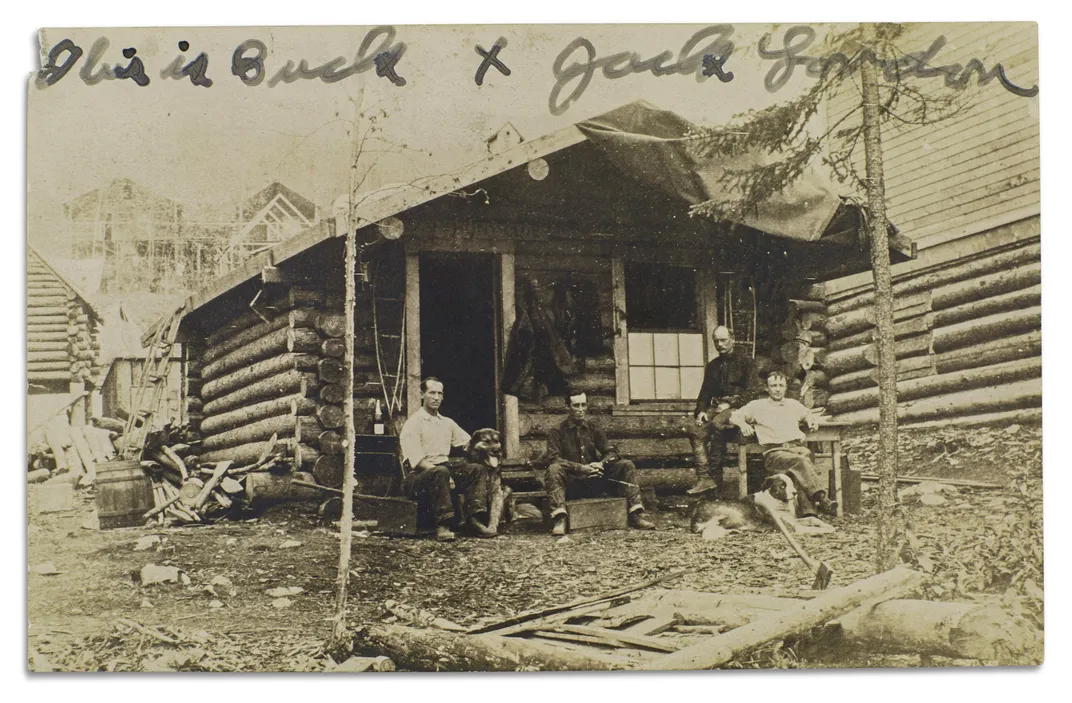

Jack befriended two brothers, Louis and Marshall Bond, who let him camp next to their cabin in Dawson. Their father was a wealthy judge with a ranch in Santa Clara, California; he would later appear, lightly fictionalized, as Judge Miller in The Call of the Wild. Jack also befriended the Bond brothers’ dog, a magnificent, 140-pound Saint Bernard-Scotch collie mix. The dog’s name was Jack, and he was the model for Buck, the canine hero of The Call of the Wild.

Marshall Bond was struck by Jack London’s unusual rapport with dogs. Rather than talk affectionately to them, and pet them, “He always spoke and acted toward the dog as if he recognized his noble qualities, but took them as a matter of course,” Bond wrote in his memoir. “He had an appreciative and instant eye for fine traits and honored them in a dog as he would in a man.” That is a statement of the obvious to anyone who has read The Call of the Wild and London’s other great dog book, White Fang.

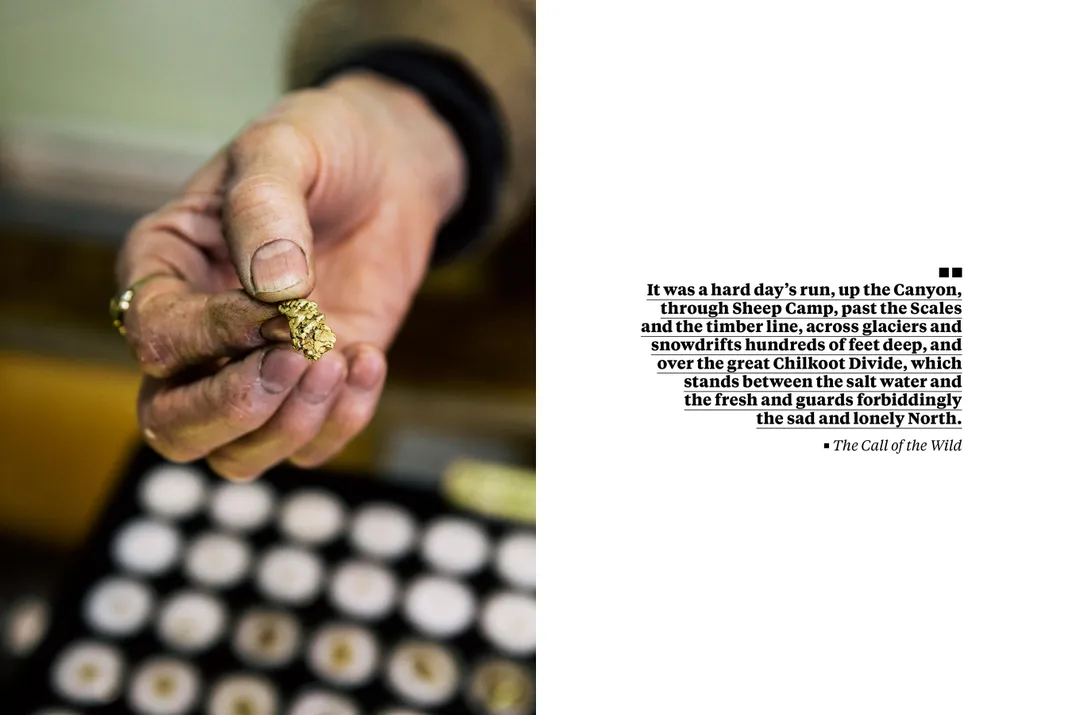

Jack stayed in Dawson for more than six weeks. Partly to keep warm, he spent a lot of time in bars, and was often seen in conversation with the “sourdoughs,” or seasoned miners. These characters thought 40 below zero was good weather for hunting and dog-sledding, and they scorned the newcomers as cheechakos, or “tenderfeet,” who were liable to start whining after three days with no food. There was so much material for a budding novelist in those gaudy saloons, where men told tales of death outwitted and bonanza gold strikes, silk-clad women charged a dollar for a dance, $25,000 was sometimes wagered on a hand of poker, and everyone paid with gold dust or nuggets.

* * *

Dawson City today is a hardy, free-spirited, extremely remote community of 1,400 people, still trading on its history as the capital of the Klondike gold rush. It’s a place where oddballs, artists, the First Nation Trondek Hwechin and others can live at their own pace and with a minimum of judgment. Even in an era when industrial-scale mining has been introduced in the region, independent gold miners are still digging and sluicing in the nearby Klondike Valley, using excavators and diesel pumps, as well as shovels and gold pans. Some of them are finding significant amounts of gold, and spending their money on whiskey, poker, blackjack and can-can shows at Diamond Tooth Gerties gambling hall.

The downtown streets are unpaved. You walk on raised wooden sidewalks past frontier-style buildings, some dating back to the gold rush era. At the Downtown Hotel is the Jack London Grill and a saloon that serves a highly unusual cocktail, the Sourtoe—a severed, mummified human toe dropped into the liquor of your choice. The legend is that the drink dates back to the 1920s, and originally involved an amputated frostbitten toe. These days, according to the bartender, the saloon accepts toes lost to other misfortunes, including lawnmower accidents.

I ordered mine with Wild Turkey, and it was served by the Sourtoe Captain, a young man with a patch of green hair wearing a captain’s hat. Opening a wooden chest, he retrieved a long brown shriveled toe from a jar of salt, dropped it into the shot glass, warned of a $2,500 fine for chewing or swallowing, and then said, “You can drink it fast or drink it slow, but your lips must touch the gnarly toe.” When the deed was done, he presented me with a certificate suitable for framing.

By providential coincidence, the Sourtoe Captain’s mother, a filmmaker named Lulu Keating, was working on a documentary about Jack London’s time in the Yukon. She took me to an ancient dive bar called the Pit with dramatically sloping floors and a raunchy oil painting on the wall. The customers included gold miners, a professor, a dancer and a musician.

“This is a land of characters, then and now, and Jack mined them,” said Keating. “He was fiercely intelligent, and had a lot of confidence, but instead of trying to impress people, he looked and listened and felt. That’s what made him a good writer.”

On her iPad, she showed me copies of letters that Jack wrote to people in Dawson after he left, requesting stories, details, flavor and gossip. She also had a letter written by Father Judge, a Catholic priest, in which he describes falling through river ice and just managing to build a fire to save his life. Jack knew Father Judge, and almost certainly borrowed the incident for his famous short story “To Build a Fire.” After generously sharing her research, she sent me up the hill to see Jack’s cabin, moved to Dawson City from its original location, and the small Jack London Museum.

In December 1897, at the coldest, darkest time of year, Jack left Dawson and snowshoed 80 miles up the frozen Yukon River, sleeping under blankets next to a fire. Weather records, and Jack’s recollections, indicate temperatures close to 70 below zero. Reaching the Stewart River, he joined his three partners in one of the log cabins they had found. It was 10 by 12, and even when the metal stove was red hot, meat would stay frozen on a shelf eight feet away.

They lived on sourdough bread, beans and bacon, supplemented by game meat, and they chopped water out of the river with an ax. Thawing the ground with fires, they dug for gold but found very little. They played a lot of cards, and visited back and forth with men in other cabins. Jack’s company was valued because he was an excellent conversationalist and storyteller, with a cheerful, generous personality. Nearly all the men on the Stewart River that winter ended up in his fiction, and one of them, a broad-shouldered, big-hearted prospector named John Thorson, became John Thornton, Harrison Ford’s character in The Call of the Wild.

In 1965, literary sleuth Dick North, traveling by dog sled through the snow, found the derelict cabin where London spent his first and only winter in the area. He was able to identify it because Jack had signed and dated his name on the wall. Handwriting experts confirmed the signature as genuine. The cabin was then dismantled, and its logs included in two replicas—one in Jack London Square in Oakland, California, the other in Dawson City at Eighth Avenue where the poet Robert Service used to live.

There’s no exaggerating how primitive the cabin is, or how cramped and smelly it must have been with four men living in it. They slept on spruce boughs and animal hides. The floor was ice and snow. When they ran out of candles, they burned bacon grease in a homemade lamp, and Jack smoked incessantly. They all got scurvy, or “Arctic leprosy,” from the lack of fresh vegetables and exercise. The disease killed many prospectors in the Klondike, and put an end to Jack’s brief career as a miner.

When the river unfroze in May 1898, he and another man dismantled a cabin, turned it into a raft, floated down to Dawson City, and sold the logs for $600. Jack managed to find some potatoes and a lemon, which relieved his symptoms, and at Father Judge’s hospital he was told to get to fresh food as soon as possible.

With John Thorson and another man, London set off down the Yukon River in a small rowboat. Weakened by scurvy, they had to row 1,500 river miles to the Bering Sea, where they hoped to catch a ship to Seattle or San Francisco.

On the day they left Dawson, Tuesday June 8, Jack started keeping a journal in gray and then purple pencil on loose lined notepapers. It was a thrill to see the original in his collected papers at the Huntington Library in California, but it proved a fairly dull read—brief notes about places reached and small incidents of travel, a few descriptive passages, very little about himself. Only once does he mention his scurvy, “which has now almost entirely crippled me from the waist down.” He is more concerned with the torments inflicted by “thousands of millions” of mosquitoes biting “through overalls and heavy underwear.”

At the end of June, after a tough but fairly uneventful journey, they reached St. Michaels on the Alaskan coast, and Jack landed a job as a coal-shoveler on a steamship heading to San Francisco. The final entry in the journal is: “Leave St. Michaels—unregrettable moment.”

* * *

That summer the Klondike gold rush reached its full frenzy. The population of the Klondike region exploded to more than 30,000, with about half in Dawson City. A lucky few did become fantastically rich. Swede Anderson dug out a million dollars in gold from a claim that everyone said was worthless. But the great majority of rushers found no gold, and many didn’t even try, because almost every gold-bearing creek within 50 miles of Dawson had already been claimed. By the end of summer in 1899, the rush was over, and Dawson City’s population had shrunk.

When Jack London reached San Francisco, he made a slow recovery from scurvy, and then started writing articles, essays, poems and short stories. He threw himself into it with characteristic energy, often working 18 hours a day, and he read as much as possible, studying the formulas for commercial success. But everything he submitted for publication was rejected, and he grew depressed and disheartened. Finally, Overland Monthly magazine offered to publish a Klondike short story, “To the Man on the Trail,” if he could content himself with the meager payment of $5. Flat broke, Jack accepted, and had to borrow a dime to buy the issue when it came out in January 1899.

Later that year, he hit literary paydirt. He sold “An Odyssey of the North” to the Atlantic for $120, and after that, he never looked back. It was the golden age of American magazines, editors were looking for vivid action-packed short fiction, and Jack London, through hard work, perseverance, and trial and error mastered the form. Within two years of leaving the Klondike, he was the best-paid short story writer in America. By the age of 24, London was famed as the “American Kipling.”

The idea for The Call of the Wild, London’s seventh book and arguably his best, came to him in 1903 after a depressing stint as an undercover journalist in the slums of London’s East End. He started thinking back to the pristine Yukon wilderness and that 140-pound Saint Bernard mix in Dawson, the northern lights and the sled-dog teams racing through the snow in 50 below zero temperatures. He intended to write a 4,000-word short story honoring a dog, but it “got away from me,” as he later said, and reached more than 30,000 words before he could call a halt.

He wrote it in a month in a creative fever dream. He sent the manuscript to the head of Macmillan Publishing, George Platt Brett, who recognized it as a masterpiece and made one of the most profitable deals in the company’s history. He offered $2,000 for the full rights. Jack needed the money, so he accepted. The book, an immediate best seller, has remained in print all over the world.

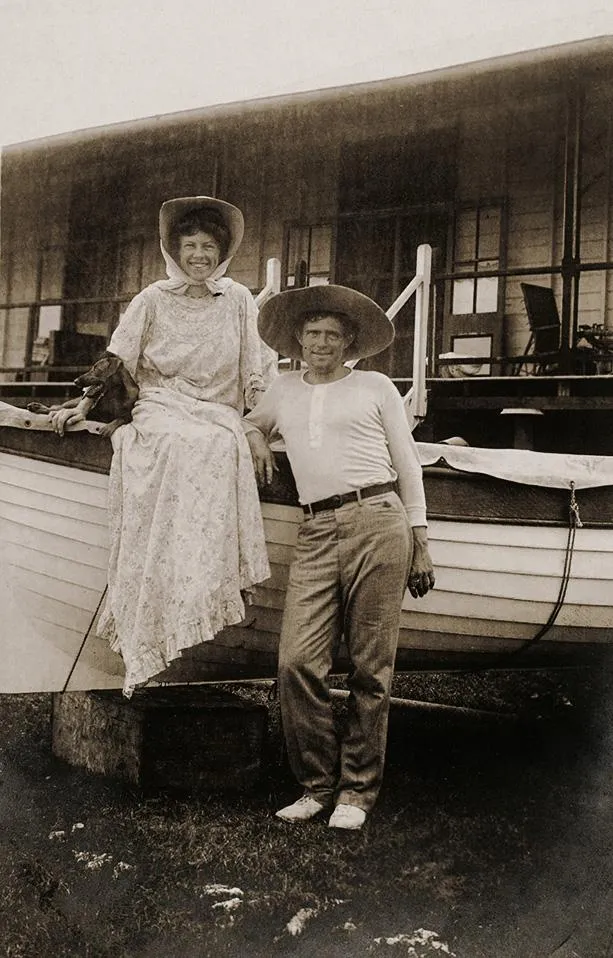

Jack London, who unabashedly wrote for money, never received a penny in royalties for The Call of the Wild. Nor did he ever complain about it. As he told his wife. Charmian, “Mr. Brett took a gamble, and a big chance to lose. It was the game, and I have no kick.”

He was already well-known when the book was published, and its success turned him into a full-blown international celebrity. He was earning $10,000 a month from books, articles, journalistic assignments and speaking engagements, and barely keeping up with his expenses. He was one of the first writers to live in the headlines, and he spent money like a movie star. He sailed across the South Pacific in a ruinously expensive custom-built boat. He bought a 1,000-acre estate in Sonoma County and built a 15,000-square-foot mansion there, Wolf House, which burned down just before he moved in.

He never lost his taste for adventure. He worked as a war correspondent in Korea and Japan, and later covered the Mexican Revolution. He lived in Hawaii and Australia. From his prolific pen flowed 23 novels, several books of nonfiction, seven plays, and hundreds of poems and short stories. Of his fictional works—novels and short stories—more than 80 were set in the Far North and drawn from the nine months that he spent there. It continued to sustain him, much as Joseph Conrad drew lifelong inspiration from his youthful adventures at sea.

At the time of his death in 1916—he was 40 and died of kidney disease exacerbated by alcoholism—Jack London was one of the most widely read authors in the world. Although the writer later was praised by such luminaries as George Orwell and Jorge Luis Borges, his reputation went into decline after his death. The American literary elite dismissed him as a hack who produced popular novels about dogs and wolves. According to London’s biographer, Earle Labor, these critics were both unfamiliar with the range of London’s work—he also wrote about philosophy, war, astral projection, politics and many other subjects—and also misled by the tough “plain style” that London pioneered. “Even his popular classics are enriched with multilevel meanings beneath the action-packed surface,” Labor says. “Jack was gifted with what Jung called ‘primordial vision,’ which unconsciously connects the author to universal myths and archetypes. He has influenced countless other writers, including Ernest Hemingway, James Jones and Susan Sontag.”

In recent decades, according to Labor, there has been an “exponential outpouring” of Jack London scholarship, geared toward reclaiming his reputation. “His international status—both as an outstanding writer and as a major public figure—has always been exceptionally high,” Labor adds. “Now he’s finally achieving recognition in his own country as a major author for all literary seasons.”

*Editor’s Note, 12/10/2021: An earlier version of this story stated incorrect figures for the population of Dawson City during the Gold Rush.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f5/19/f519bd94-5bb8-4d51-9cfe-777562f3a4ff/5nov2019_a04_jacklondon.jpg)