Goodbye, Columbus

A new survey upends the conventional wisdom about who counts in American history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/presence_may08_631.jpg)

Let's begin with a brief exercise. Who are the most famous Americans in history, excluding presidents and first ladies? Go ahead—list your top ten. I can wait. (Go ahead, use the comments section below.)

A colleague and I recently put this question to 2,000 11th and 12th graders from all 50 states, curious to see whether they would name (as a great many educators had predicted) the likes of Paris Hilton, Britney Spears, Tupac Shakur, 50 Cent, Barry Bonds, Kanye West or any number of other hip-hop artists, celebrities or sports idols. To our surprise, the young people's answers showed that whatever they were reading in their history classrooms, it wasn't People magazine. Their top ten names were all bona fide historical figures.

To our even greater surprise, their answers pretty much matched those we gathered from 2,000 adults age 45 and over. From this modest exercise, we deduced that much of what we take for conventional wisdom about today's youth might be conventional, but it is not wisdom. Maybe we've spent so much time ferreting out what kids don't know that we've forgotten to ask what they do know.

Chauncey Monte-Sano of the University of Maryland and I designed our survey as an open-ended exercise. Rather than giving the students a list of names, we gave them a form with ten blank lines separated by a line in the middle. Part A came with these instructions: "Starting from Columbus to the present day, jot down the names of the most famous Americans in history." There was only one ground rule—no presidents or first ladies. Part B prompted for "famous women in American history" (again, no first ladies). Thus the questionnaire was weighted toward women, though many kids erased women's names from the first section before adding them to the second. But when we tallied our historical top ten, we counted the total number of times a name appeared, regardless of which section.

Of course a few kids clowned around, but most took the survey seriously. About an equal number of kids and adults listed Mom; from adolescent boys we learned that Jenna Jameson is the biggest star of the X-rated movie industry. But neither Mom nor Jenna was anywhere near the top. Only three people appeared on 40 percent of all questionnaires. All three were African-American.

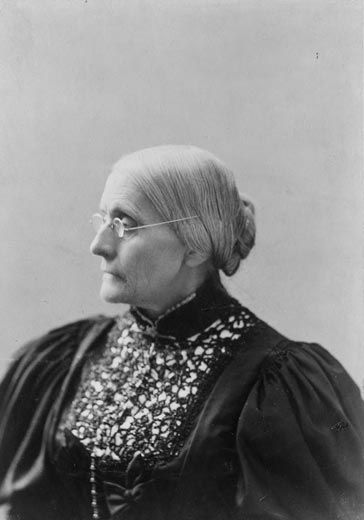

For today's teens, the most famous American in history is...the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., appearing on 67 percent of all lists. Rosa Parks was close behind, at 60 percent, and third was Harriet Tubman, at 44 percent. Rounding out the top ten were Susan B. Anthony (34 percent), Benjamin Franklin (29 percent), Amelia Earhart (23 percent), Oprah Winfrey (22 percent), Marilyn Monroe (19 percent), Thomas Edison (18 percent) and Albert Einstein (16 percent). For the record, our sample matched within a few percentage points the demographics of the 2000 U.S. Census: about 70 percent of our respondents were white, 13 percent African-American, 9 percent Hispanic, 7 percent Asian-American, 1 percent Native American.

What about the gap between our supposedly unmoored youth and their historically rooted elders? There was not much of one. Eight of the top ten names were identical. (Instead of Monroe and Einstein, adults listed Betsy Ross and Henry Ford.) Among both kids and adults, neither region nor gender made much difference. Indeed, the only consistent difference was between races, and even there it was only between African-Americans and whites. Whites' lists comprised four African-Americans and six whites; African-Americans listed nine African-American figures and one white. (The African-American students put down Susan B. Anthony, the adults Benjamin Franklin.)

Trying to take the national pulse by counting names is fraught with problems. To start, we know little about our respondents beyond a few characteristics (gender, race/ethnicity and region, plus year and place of birth for adults). When we tested our questionnaire on kids, we found that replacing "important" with "famous" made little difference, but we used "famous" with adults for the sake of consistency. Prompting for women's names obviously inflated their total, though we are at a loss to say by how many.

But still: such qualifications cannot mist the clarity of consensus we found among Americans of different ages, regions and races. Eighty-two years after Carter G. Woodson founded Negro History Week, Martin Luther King Jr. has emerged as the most famous American in history. This may come as no surprise—after all, King is the only American whose birthday is celebrated by name as a national holiday. But who would have predicted that Rosa Parks would be the second most named figure? Or that Harriet Tubman would be third for students and ninth for adults? Or that 45 years after the Civil Rights Act was passed, the three most common names appearing on surveys in an all-white classroom in, say, Columbia Falls, Montana, would belong to African-Americans? For many of those students' grandparents, this moment would have been unimaginable.

In the space of a few decades, African-Americans have moved from blurry figures on the margins of the national narrative to actors on its center stage. Surely multicultural education has played a role. When textbooks of the 1940s and '50s employed the disingenuous clause "leaving aside the Negro and Indian population" to sketch the national portrait, few cried foul. Not today. Textbooks went from "scarcely mentioning" minorities and women, as a 1995 Smith College study concluded, to "containing a substantial multicultural (and feminist) component" by the mid-1980s. Scanning the shelves of a school library—or even the youth biography section at your local mega-chain bookstore—it's hard to miss this change. Schools, of course, influence others besides students. Adults learn new history from their children's homework.

Yet, to claim that the curriculum alone has caused these shifts would be simplistic. It wasn't librarians, but members of Congress who voted for Rosa Parks' body to lie in honor in the Capitol Rotunda after she died in 2005, the first woman in American history to be so honored. And it wasn't teachers, but officials at the United States Postal Service who in 1978 made Harriet Tubman the first African-American woman to be featured on a U.S. postage stamp (and who honored her with a second stamp in 1995). Kids learn about Martin Luther King not only in school assemblies, but also when they buy a Slurpee at 7-Eleven and find free copies of the "I Have a Dream" speech by the cash register.

Harriet Tubman's prominence on the list was something we wouldn't have predicted, particularly among adults. By any measure, Tubman was an extraordinary person, ferrying at least 70 slaves out of Maryland and indirectly helping up to 50 more. Still, the Underground Railroad moved 70,000 to 100,000 people out of slavery, and in terms of sheer impact, lesser-known individuals played larger roles—the freeman David Ruggles and his Vigilance Committee of New York, for example, aided a thousand fugitives during the 1830s. The alleged fact that a $40,000 bounty (the equivalent of $2 million today) was offered for her capture is sheer myth, but it has been printed over and over again in state-approved books and school biographies.

In other words, Tubman may be our new Betsy Ross—someone whose place in our national memory is assured by her symbolic star power. Ross' storied needlework, as Harvard University's Laurel Thatcher Ulrich has shown, has as much credibility as Parson Weems' tall tale of little George Washington's cherry tree. Still, a quarter-million visitors flock annually to the Betsy Ross House in Philadelphia.

It's much easier to document the accomplishments of the only living person to appear in the top ten list. Oprah Winfrey is not just one of the richest self-made women in America. She is also a magazine publisher, life coach, philanthropist, kingmaker (think Dr. Phil), advocate for survivors of sexual abuse, school benefactor, even spiritual counselor. In a 2005 Beliefnet poll, more than a third of the respondents said she had "a more profound impact" on their spirituality than their pastor.

Some people might point to the inclusion of a TV talk-show host on our list as an indication of decline and imminent fall. I'd say that gauging Winfrey's influence by calling her a TV host makes as much sense as sizing up Ben Franklin's by calling him a printer. Consider the parallels: both rose from modest means to become the most identifiable Americans of their time; both became famous for serving up hearty doses of folk wisdom and common sense; both were avid readers and powerful proponents of literacy and both earned countless friends and admirers with their personal charisma.

Recently, the chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, Bruce Cole, worried that today's students don't learn the kind of history that will give them a common bond. To remedy this, he commissioned laminated posters of 40 famous works of art to hang in every American classroom, including Grant Wood's 1931 painting "The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere." "Call them myths if you want," Cole said, "but unless we have them, we don't have anything."

He can relax. Our kids seem to be doing just fine without an emergency transfusion of laminated artwork. Myths inhabit the national consciousness the way gas molecules fill a vacuum. In a country as diverse as ours, we instinctively search for symbols—in children's biographies, coloring contests, Disney movies—that allow us to rally around common themes and common stories, whether true, embellished or made out of whole cloth.

Perhaps our most famous national hand-wringer was Arthur Schlesinger Jr., whose 1988 Disuniting of America: Reflections on a Multicultural Society predicted our national downfall. "Left unchecked," he wrote, the "new ethnic gospel" is a recipe for "fragmentation, resegregation and tribalization of American life."

If, like Schlesinger (who died last year), Monte-Sano and I had focused on statements by the most extreme multiculturalists, we may have come to a similar conclusion. But that's not what we did. Instead, we gave ordinary kids in ordinary classrooms a simple survey and compared their responses with those from the ordinary adults we found eating lunch in a Seattle pedestrian mall, shopping for crafts at a street fair in Philadelphia or waiting for a bus in Oklahoma City. What we discovered was that Americans of different ages, regions, genders and races congregated with remarkable consistency around the same small set of names. To us, this sounds more like unity than fragmentation.

The common figures who draw together Americans today look somewhat different from those of former eras. While there are still a few inventors, entrepreneurs and entertainers, the others who capture our imagination are those who acted to expand rights, alleviate misery, rectify injustice and promote freedom. That Americans young and old, in locations as distant as Columbia Falls, Montana, and Tallahassee, Florida, listed the same figures seems deeply symbolic of the story we tell ourselves about who we think we are—and perhaps who we, as Americans, aspire to become.

Sam Wineburg is a professor of education and history at Stanford University.