The Grand Coulee Powers On, 75 Years After Its First Surge of Electricity

A look back at how the powerful dam came to be

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b1/d7/b1d77e74-9eb2-43e4-b4cc-3f1d11ec7804/8e01538v-resize.jpg)

The Columbia River roared, the generators in the Grand Coulee Dam began to whir, and the mile-long dam put the nation’s fourth-largest river to work. It was March 22, 1941, and 8,000 people were gathered at the great canyon 100 miles northwest of Spokane, Washington, to see the federal government put its most audacious public-works project into action.

Chief Jim James of the San Poil tribe, the dam’s reluctant neighbors, pressed the button that sent its first jolt of electricity to the outside world. A high school band played “America, the Beautiful” above the sounds of nature and machine.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s dedication message, sent from Washington, D.C., spoke of the Grand Coulee’s power. “A tremendous stream of energy,” FDR wrote, “[will] turn factory wheels to make the lives of men more fruitful. It will light homes and stores in towns and cities.” Interior secretary Harold Ickes’ statement spoke directly to the Grand Coulee’s size: “The dam alone comprises the greatest single structure man has built.”

Grand Coulee’s sheer size makes it a monument and a metaphor. It’s one of the largest concrete structures in the world, with 12 million cubic yards of concrete, enough to pave a transcontinental highway. It’s 550 feet tall from top to foundation, just five feet shy of the height of the Washington Monument. Though not quite as tall as America’s other famed public-works colossus, the 726-foot-tall Hoover Dam, it’s several times more massive, a mile long to Hoover Dam’s quarter-mile.

Even its canyon namesake was enormous. Coulee, with Canadian-French etymology, usually means a small ravine, a gully. But Washington’s Grand Coulee was a 50-mile-long, dry valley with steep, 600-foot-high walls, carved through volcanic rock by a flood as the last ice age ended and ice choked off the Columbia River. The dam was built nearby, where two cliffs stand astride a river bend.

A small-town newspaper editor with massive ambitions championed the dam. Rufus Woods, editor of north-central Washington’s Wenatchee Daily World, believed damming the Columbia would transform the arid land around his apple-picking town into a verdant, populous paradise. “Wearing a bowler tipped low over his forehead, indoors and out, he exuded self-confidence, even cockiness,” wrote Woods’ biographer, Robert E. Ficken. From 1918, when Woods first heard the idea from local attorney William Clapp, Woods crusaded for the dam with grand pronouncements in capital letters. The heat and light from the dam, he wrote, “WOULD BE THE MOST UNIQUE, THE MOST INTERESTING, AND THE MOST REMARKABLE DEVELOPMENT… IN THE AGE OF INDUSTRIAL AND SCIENTIFIC MIRACLES.”

In October 1932, Woods, a lifelong Republican, pitched the dam proposal to President Herbert Hoover at the White House, arguing it would provide jobs for thousands at the depth of the Great Depression. Hoover turned him down, saying there was no market in remote central Washington for more electric power. But before Roosevelt even ran against Hoover, he promised Senator Clarence Dill of Washington that he’d build the dam were he elected. Dill, sensing an opportunity, talked FDR up as a potential president to his Senate colleagues and the press, then campaigned for him in fall 1932 across the Pacific Northwest and the Midwest. Once FDR beat Hoover and authorized preliminary funding for the dam under the authority of the National Industrial Recovery Act, Woods was happy to forge an alliance with FDR and Dill, Democrats he once disparaged.

Like other big dams on western rivers, Grand Coulee fit Roosevelt’s sweeping ambitions for the New Deal: jobs for men on relief, planned prosperity for vast rural regions, new opportunity for the destitute migrant. During a 1934 visit to the Grand Coulee’s remote construction site, FDR declared, “This country, which is pretty bare today, is going to be filled with the homes… of a great many families from other states of the union,” His wife, who came along, was unimpressed. “It was a good salesman who sold this to Franklin,” Eleanor Roosevelt said.

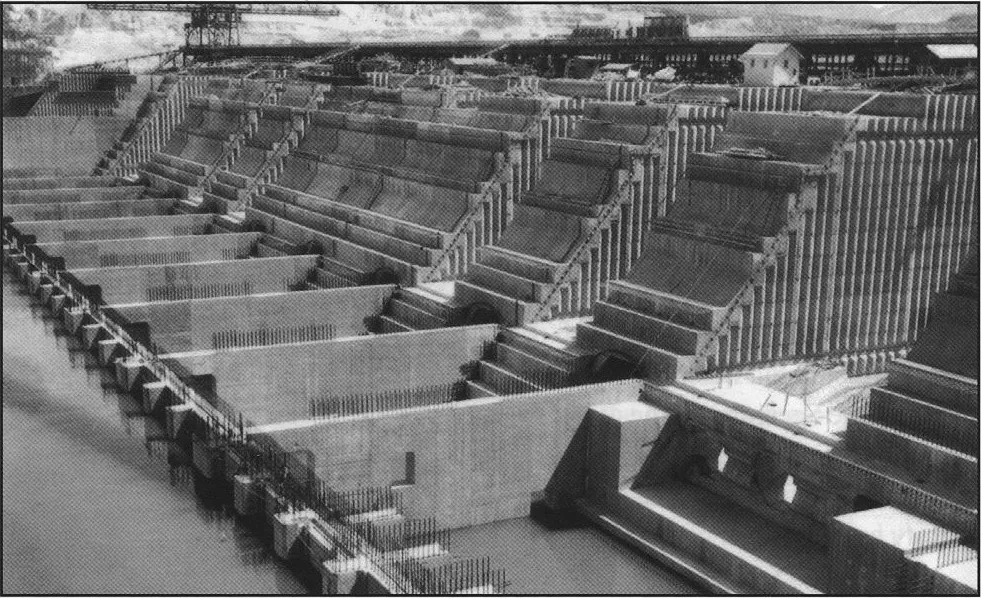

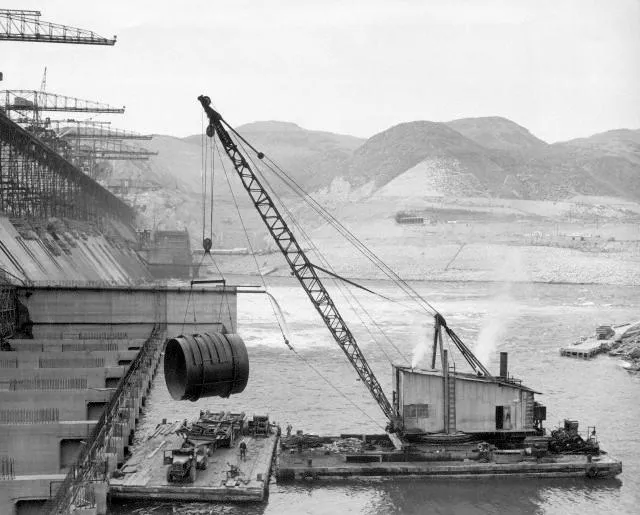

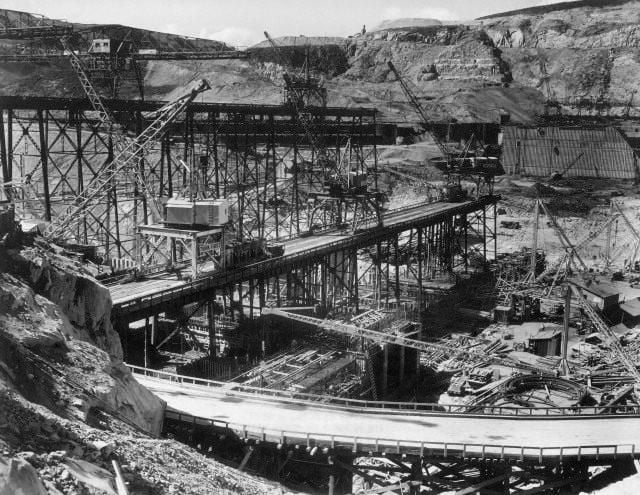

The dam took eight years and more than 100 million man-hours to build. Massive temporary cofferdams diverted half the river to allow work on the foundation, then the other half. Seventy-seven workers were killed -- some drowned, some fallen, some crushed. (Industrial fatalities were more common then: 96 workers died building the Hoover Dam, and 60 died in the construction of the Fort Peck Dam in Montana, including six workers buried in the concrete after a 1938 landslide.) The Grand Coulee Dam emptied the upper Columbia River of the salmon that would swim hundreds of miles upstream to spawn. For a few years afterward, they swam up as far as the dam; after that, they stopped coming. (The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the agency that oversees the West’s dams, power plants and canals, offers various reasons why the Grand Coulee has no fish ladders even today.)

Behind the dam, the Columbia swelled into a 150-mile-long lake. In 1940, the Native Americans of the Colville Indian Reservation watched their ancestors’ burial grounds and their salmon-fishing spot at the Columbia’s Kettle Falls forever submerged under its rising waters. Though Chief James of the San Poil helped drive the dam’s first stake in 1933 and flipped the ceremonial first switch in 1941, the area’s native people still mourn the damage done. Today, a bill to compensate the Spokane tribe is pending before Congress.

The Grand Coulee’s critics called it a white elephant in the desert, skeptical of the need for it in the dry, empty stretch of eastern Washington nicknamed the Channeled Scabland. “Up in the Grand Coulee area there is no one to sell the power to except the jack rabbits and the rattlesnakes,” complained Rep. Francis Culkin of New York, “and they are not amenable, as you know, to the ordinary processes of an electric meter.” World War II proved the critics wrong. Its electricity powered the aluminum plants of the Pacific Northwest and the Manhattan Project’s Hanford Site along the Columbia River, which generated the plutonium for the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki. Official hype declared that the dam won the war for the Allies. Without Grand Coulee, President Harry Truman claimed in 1948, “it would have been almost impossible to win this war.” Historian Paul Pitzer argues in his book Grand Coulee: Harnessing a Dream, however, that the government could have diverted power from civilian uses to the war effort had the dam not been built.

The most eloquent celebration of Grand Coulee Dam came not from Truman or FDR, but Woody Guthrie. In May 1941, two months after the dam was dedicated, the legendary folk singer drove north from California in a banged-up Pontiac to write about the monumental dam, which he would soon compare to the seven wonders of the world. The federal Bonneville Power Administration hired Guthrie for 30 days at $266 to write songs for a documentary about the dam. Chauffeured in a black 1940 Hudson, Guthrie traveled hundreds of miles along the cascading Columbia River, from Portland to the Grand Coulee Dam, where he got a tour from the head contractor. In one month, Guthrie wrote 26 songs inspired by the Columbia River and the Grand Coulee Dam. The best were Whitman-esque, lyrical and rambling, overflowing with details invoking American possibility: “She winds down the granite canyon and bends across the lea,/Like a prancin’, dancin’ stallion down her sea-way to the sea./Cast your eyes upon the biggest thing that’s built by human hands,/On the king Columbia River, it’s the big Grand Coulee Dam.”

Grand Coulee Dam’s real place in American history needs no embellishment. Though its irrigation projects didn’t remake the land as Roosevelt imagined (and Woods’ Wenatchee is still mostly known for its apples), the dam’s electricity powered the growth of the Pacific Northwest. Today, Grand Coulee is still the United States’ largest hydrogenerator of electric power, supplying electricity to the entire western United States, from Washington state to New Mexico, as well as parts of Canada. It generates 21 billion kilowatt-hours, enough to power 2 million homes for a year. A million visitors a year travel to rural Washington State to visit the Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area, and the dam remains the greatest monument to the New Deal’s epic remaking of the American landscape.