The Great Fire of London Was Blamed on Religious Terrorism

Why scores of Londoners thought the fire of 1666 was all part of a nefarious Catholic conspiracy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/87/38/87384ed1-094b-4f3b-909d-ceb66620d741/oil_painting_of_the_great_fire_of_london_seen_from_newgate_c_museum_of_london.jpg)

The rumors spread faster than the blaze that engulfed London over five days in September 1666: that the fire raging through the city’s dense heart was no accident – it was deliberate arson, an act of terror, the start of a battle. England was at war with both the Dutch and the French, after all. The fire was a “softening” of the city ahead of an invasion, or they were already here, whoever “they” were. Or maybe it was the Catholics, who’d long plotted the downfall of the Protestant nation.

Londoners responded in kind.

Before the flames were out, a Dutch baker was dragged from his bakery while an angry mob tore it apart. A Swedish diplomat was nearly hung, saved only by the Duke of York who happened to see him and demand he be let down. A blacksmith “felled” a Frenchman in the street with a vicious blow with an iron bar; a witness recalled seeing his “innocent blood flowing in a plentiful stream down his ankles”. A French woman’s breasts were cut off by Londoners who thought the chicks she carried in her apron were incendiaries. Another Frenchman was nearly dismembered by a mob that thought that he was carrying a chest of bombs; the bombs were tennis balls.

“The need to blame somebody was very, very strong,” attests Adrian Tinniswood, author of By Permission of Heaven: The Story of the Great Fire. The Londoners felt that “It can’t have been an accident, it can’t be God visiting this upon us, especially after the plague, this has to be an act of war.”

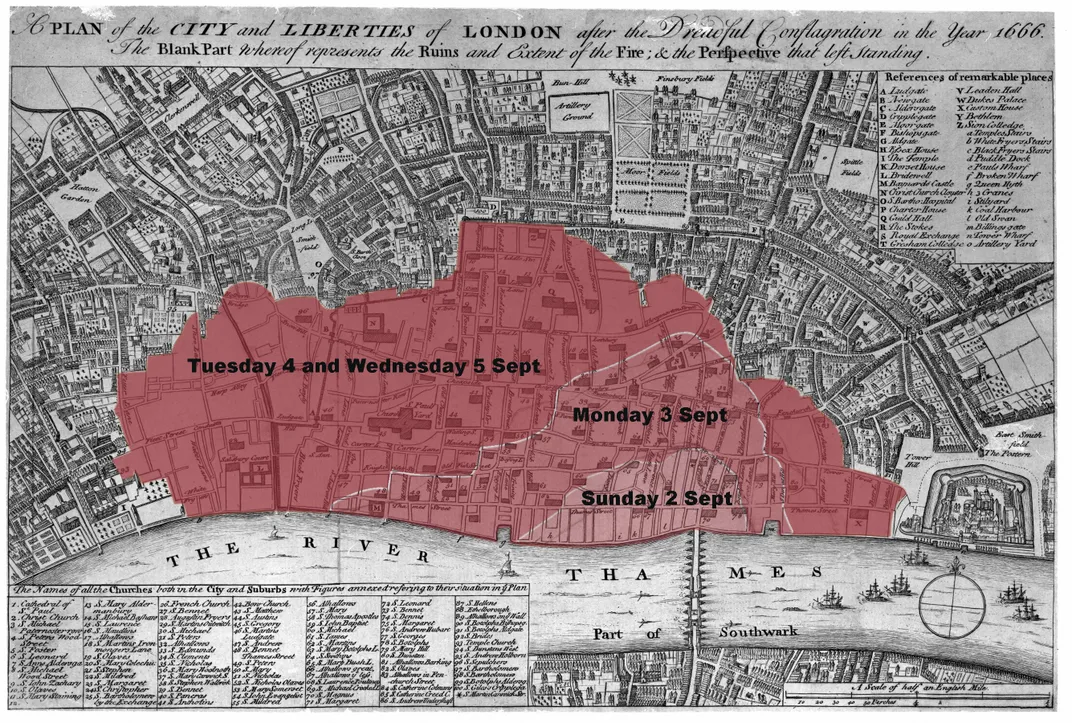

As far as we know, it wasn’t. The fire started in the early hours of the morning of September 2 on Pudding Lane in the bakery of Thomas Farriner. Pudding Lane was (and still is) located in the centre of the City of London, the medieval city of around one square mile ringed by ancient Roman walls and gates and rivers now covered and forgotten. Greater London built up around these walls in the years after the Romans left in the 4th century, sprawling out in all directions, but the City of London remained (and still remains) its own entity, with its own elected Mayor and home to around 80,000 people in 1666. That number would have been higher, but the Black Plague had killed roughly 15 percent of the entire city’s population the previous year.

Farriner was a maker of hard tack, the dry but durable biscuits that fed the King’s Navy; he’d closed for business on Saturday, September 1, at around 8 or 9 that night, extinguishing the fire in his oven. His daughter, Hanna, then 23, checked the kitchen at around midnight, making sure the oven was cold, then headed to bed. An hour later, the ground floor of the building was filled with smoke. The Farriners’ manservant, Teagh, raised the alarm, climbing to the upper floors where Thomas, Hanna, and their maid slept. Thomas, Hanna, and Teagh squeezed out of a window and scrambled along the gutter to a neighbor’s window. The maid, whose name remains unknown, did not and was the first to die in the fire.

At first, few were overly concerned about the fire. London was a cramped, overcrowded city lighted by candles and fireplaces. Buildings were largely made of wood; fires were common. The last major fire was in 1633, destroying 42 buildings at the northern end of London Bridge and 80 on Thames Street, but there were smaller fires all the time. The City of London’s Lord Mayor at the time, Sir Thomas Bloodworth, will ever be remembered as the man who declared that the 1666 fire was so small, “a woman might piss it out”. But Bloodworth, described by diarist Samuel Pepys as a “silly man”, wasn’t the only one to underestimate the fire: Pepys himself was woken at 3 that morning by his maid, but when he saw that the fire still seemed to be on the next street over, went back to sleep until 7. The London Gazette, the city’s twice-weekly newspaper, ran a small item about the fire in its Monday edition, among gossip about the Prince of Saxe’s unconsummated marriage to the Princess of Denmark and news of a storm in the English Channel.

A second report on the fire that week, however, was not forthcoming. Within hours of printing Monday’s paper, the Gazette’s press burned to the ground. By the time the newspaper had hit the streets, Londoners were very much aware that the fire that the Gazette reported “continues still with great violence” had yet to abate.

Several factors contributed to the fire’s slow but unstoppable spread: Many of the residents of Pudding Lane were asleep when the fire began and slow to react, not that they could have done much beyond throw buckets of whatever liquid – beer, milk, urine, water – was on hand. A hot summer had left London parched, its timber and plaster buildings like well-dried kindling. These buildings were so close together that people on opposite sides of the narrow, filthy streets could reach out their windows and shake hands. And because London was the manufacturing and trade engine of England, these buildings were also packed with flammable goods – rope, pitch, flour, brandy and wool.

But by Monday evening, Londoners began to suspect that this fire was no accident. The fire itself was behaving suspiciously; it would be subdued, only to break out somewhere else, as far as 200 yards away. This led people to believe that the fire was being intentionally set, although the real cause was an unusually strong wind that was picking up embers and depositing them all over the city.

“This wind blowing from the east was forcing the fire across the city much quicker than people were expecting,” explains Meriel Jeater, curator of the Museum of London’s “Fire! Fire! Exhibition,” commemorating the 350th anniversary of the fire. Sparks would fly up and set fire to whatever they landed on. “It seemed that suddenly, another building was on fire and it was, ‘Why did that happen?’ They didn’t necessarily think there was spark involved, or another natural cause… England was at war, so it was perhaps natural to assume that there might have been some element of foreign attack to it.”

Embers and wind didn’t feel like a satisfying or likely answer, so Londoners started to feel around for someone to blame. And they found them.

At the time, London was the third largest city in the Western world, behind Constantinople and Paris, and roughly 30 times larger than any other English town. And it was international, with trade links all over the world, including countries that it was at war with, Holland and France, and those it wasn’t entirely comfortable with, including Spain. London was also a refuge for foreign Protestants fleeing persecution in their majority Catholic homelands, including the Flemish and French Huguenots.

That people believed that the city was under attack, that the fire was the plot of either the Dutch or the French, was logical, not paranoia. The English had just burnt the Dutch port city of West-Terschelling to the ground just two weeks earlier. As soon as the fire broke out, Dutch and French immigrants were immediately under suspicion; as the fire burned, the English authorities stopped and interrogated foreigners at ports. More troubling, however, was that Londoners began to take vengeance into their own hands, says Tinniswood. “You’re not looking at a population that can distinguish between a Dutchman, a Frenchman, a Spaniard, a Swede. If you’re not English, good enough.”

“The rumors reach a kind of crescendo on the Wednesday night when the fire is subsiding and then breaks out just around Fleet Street,” says Tinniswood. Homeless Londoners fleeing the fire were camped in the fields around the City. A rumor went up that the French were invading the city, then the cry: “Arms, arms, arms!”

“They’re traumatized, they’re bruised, and they all, hundreds and thousands of them, they take up sticks and come pouring into the city,” says Tinniswood. “It’s very real… A lot of what the authorities are doing is trying to damp down that sort of panic.”

But extinguishing the rumors proved almost as difficult as putting out the fire itself. Rumors traveled fast, for one thing: “The streets are full of people, moving their goods... They’re having to evacuate two, three, four times,” Tinniswood explains, and with each move, they’re out in the street, passing information. Compounding the problem was that there were few official ways able to contradict the rumors – not only had the newspaper’s printing press burned down, but so too did the post office. Charles II and his courtiers maintained that the fire was an accident, and though they were themselves involved in fighting the fire on the streets, there was only so much they could do to also stop the misinformation spreading. Says Tinniswood, “There’s no TV, no radio, no press, things are spread by word of mouth, and that means there must have been a thousand different rumors. But that’s the point of it: nobody knew.”

Several people judged to be foreigners were hurt during Wednesday’s riot; contemporaries were surprised that no one had been killed. The next day, Charles II issued an order, posted in places around the city not on fire, that people should “attend the business of quenching the fire” and nothing else, noting that there were enough soldiers to protect the city should the French actually attack, and explicitly stating that the fire was an act of God, not a “Papist plot”. Whether or not anyone believed him was another issue: Charles II had only been restored to his throne in 1660, 11 years after his father, Charles I, was beheaded by Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentarian forces. The City of London had sided with the Parliamentarians; six years later, Londoners still didn’t entirely trust their monarch.

The fire finally stopped on the morning of September 6. Official records put the number of deaths as fewer than 10, although Tinniswood and Jeater both believe that number was higher, probably more like 50. It’s still a surprisingly small number, given the huge amount of property damage: 80 percent of the city within the walls had burned, some 87 churches and 13,200 homes were destroyed, leaving 70,000 to 80,000 people homeless. The total financial loss was in the region of £9.9 million, at a time when the annual income of the city was put at only £12,000.

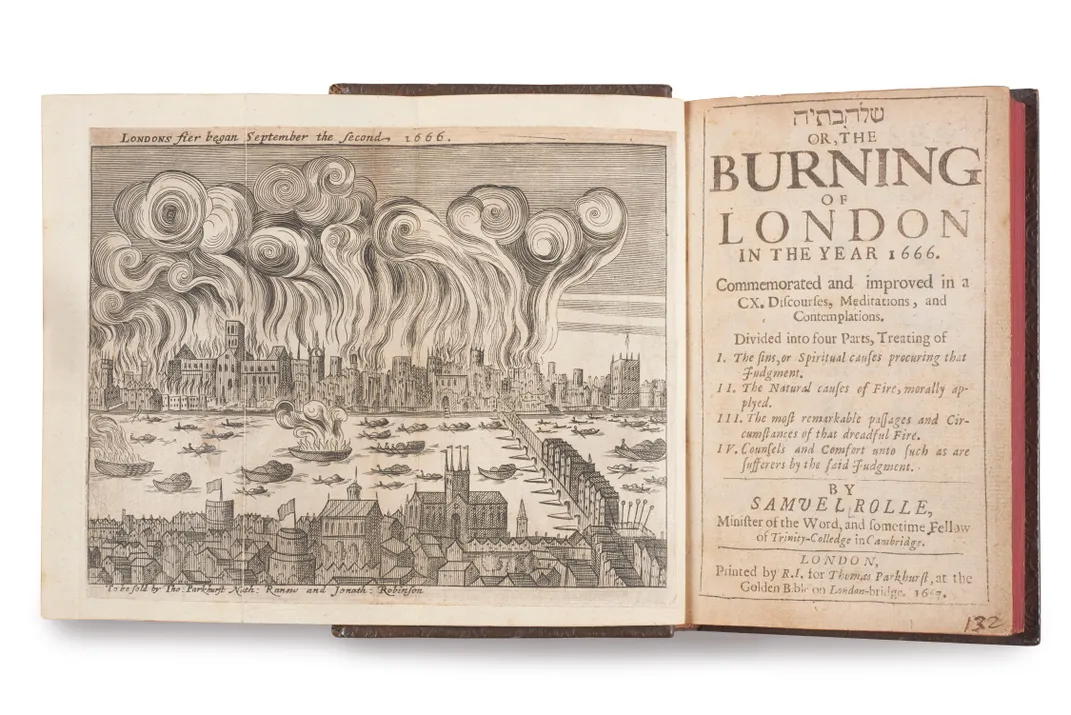

On September 25, 1666, the government set up a committee to investigate the fire, hearing testimony from dozens of people about what they saw and heard. Many were compelled to come forward with “suspicious” stories. The report was given to Parliament on January 22, 1667, but excerpts from the proceedings transcripts were leaked to the public, published in a pamphlet. By this time, just a few months after the fire, the narrative had changed. Demonstrably, the Dutch and the French hadn’t invaded, so blaming a foreign power was no longer plausible. But the people still wanted someone to blame, so they settled on the Catholics.

“After the fire, there seems be a lot of paranoia that is was a Catholic plot, that Catholics in London would conspire with Catholics abroad and force the Protestant population to convert to Catholicism,” Jeater explains. The struggle between Catholicism and Protestantism in England had been long and bloody, and neither side was above what amounted to terrorism: The Gunpowder Plot of 1605 was, after all, an English Catholic plot to assassinate James I.

The official report issued to Parliament rejected much of the testimony as unbelievable – one committee member called the allegations “very frivolous”, and the conclusion declared there was no evidence “to prove it to be a general design of wicked agents, Papists or Frenchmen, to burn the city”. It didn’t matter: The leaked excerpts did much to solidify the story that the fire was the work of shadowy Catholic agents. For example:

William Tisdale informs, That he being about the beginning of July at the Greyhound in St. Martins, with one Fitz Harris an Irish Papist, heard him say, ‘There would be a sad Desolation in September, in November a worse, in December all would be united into one.’ Whereupon he asked him, ‘where this Desolation would be?’ He answered, ‘In London.’

Or:

Mr. Light of Ratcliff, having some discourse with Mr. Longhorn of the Middle-Temple, Barrister, [reputed a zealous Papist] about February 15 last, after some discourse in disputation about Religion, he took him by the hand, and said to him, ‘You expect great things in Sixty Six, and think that Rome will be destroyed, but what if it be London?’

“You’ve got hundreds of tales like that: With hindsight, people are saying that guy said something like, ‘London better look out’,” said Tinniswood. “It’s that kind of level, it’s that vague.”

What’s even more confusing is that by the time the testimonies were leaked, someone had already confessed to and been hung for the crime of starting the fire. Robert Hubert. a 26-year-old watchmaker’s son from Rouen, France, had been stopped at Romford, in Essex, trying to make it to the east coast ports. He was brought in for questioning and bizarrely, told authorities that he’d set the fire, that he was part of a gang, that it was all a French plot. He was indicted on felony charges, transported back to London under heavy guard and installed at the White Lion Gaol in Southwark, the City’s gaols having burned down.

In October 1666, he was brought to trial at the Old Bailey. There, Hubert’s story twisted and turned – the number of people in his gang went from 24 to just four; he’d said he’d started it in Westminster, then later, after spending some time in jail, said the bakery at Pudding Lane; other evidence suggested that he hadn’t even been in London when the fire started; Hubert claimed to be a Catholic, but everyone who knew him said he was a Protestant and a Hugeunot. The presiding Lord Chief Justice declared Hubert’s confession so “disjointed” he couldn’t possibly believe him guilty. And yet, Hubert insisted that he’d set the fire. On that evidence, the strength of his own conviction that he had done it, Hubert was found guilty and sentenced to death. He was hung at Tyburn on October 29, 1666.

Why Hubert said he did it remains unclear, although there is a significant body of literature on why people confess to things they couldn’t possibly have done. Officials were in the strange position of trying to prove he hadn’t done what he said he did, but Hubert was adamant – and everyone else simply thought he was, to put it in contemporary terms, mad. The Earl of Clarendon, in his memoirs, described Hubert as a “poor distracted wretch, weary of his life, and chose to part with it this way” – in other words, suicide by confession.

Having someone to blame was certainly better than the alternative being preached from the city’s remaining pulpits: That the fire was God’s vengeance on a sinful city. They’d even named a particular sin – because the fire started at a bakery on Pudding Lane and ended at Pie Corner, opportunistic preachers took the line that Londoners were gluttonous reprobates who needed to repent now. Pie Corner is still marked with a statue of a plump golden boy, formerly known as the Fat Boy, which was intended as a reminder of London’s sinning ways.

The Catholic conspiracy story persisted for years: In 1681, the local ward erected a plaque on the site of the Pudding Lane bakery reading, “Here by the permission of Heaven, Hell broke loose upon this Protestant city from the malicious hearts of barbarous Papists, by the hand of their agent Hubert, who confessed…”. The plaque remained in place until the middle of the 18th century, when it was removed not because people had had a change of heart, but because visitors stopping to read the plaque were causing a traffic hazard. The plaque, which appears to have cracked in half, is on display at the Fire! Fire! exhibition. Also in 1681, a final line was added to the north-face inscription on the public monument to the fire: “But Popish frenzy, which wrought such horrors, is not yet quenched.” The words weren’t removed until 1830, with the Catholic Emancipation Act that lifted restrictions on practicing Catholics.

“Whenever there is a new bout of anti-Catholic sentiment, everybody harks back to the fire,” says Tinniswood. And 1681 was a big year for anti-Catholic rhetoric, prompted in part by the dragonnades in France that forced French Protestants to convert to Catholicism and, closer to home, by the so-called “Popish Plot,” a fictitious Catholic conspiracy to assassinate Charles II entirely invented by a former Church of England curate whose false claims resulted in the executions of as many as 35 innocent people.

In the immediate aftermath of the fire of 1666, London was a smoking ruin, smoldering with suspicion and religious hatred and xenophobia. And yet within three years, the city had rebuilt. Bigotry and xenophobia subsided – immigrants remained and rebuilt, more immigrants joined them later.

But that need to blame, often the person last through the door or the person whose faith is different, never really goes away. “The outsider is to blame, they are to blame, they are attacking us, we’ve got to stop them – that kind of rhetoric is sadly is very obvious… and everywhere at the moment, and it’s the same thing, just as ill-founded,” Tinniswood said, continuing, “There is still a sense that we need to blame. We need to blame them, whoever they are.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/LindaRodriguezMcRobbieLandscape.jpg.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/LindaRodriguezMcRobbieLandscape.jpg.jpeg)