The Great Los Angeles Air Raid Terrified Citizens—Even Though No Bombs Were Dropped

The WWII “battle” was an example of what happens when the threat of attack feels all too real

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/52/a9/52a937c9-4e51-4abe-98dd-f08c83a4bae4/battle_of_los_angeles_latimes-wr.jpg)

This past Saturday, residents of Hawaii were alarmed as cell phones across the island state chimed with an early morning emergency alert. “Ballistic missile threat inbound to Hawaii. Seek immediate shelter. This is not a drill,” the message read. With North Korea launching numerous missiles throughout 2017, and previously threatening to attack the U.S. territory of Guam, Hawaiian citizens—and countless tourists—were quick to assume the worst. For 38 minutes, chaos and panic reigned as people abandoned their cars on the highway to seek shelter before finally receiving word that the alert had been sent on accident.

As terrifying as the experience was for those on the archipelago, it’s not the first time an impending attack has turned out to be a false alarm. Take the Battle of Los Angeles, for instance. Never heard of it? That’s because nothing actually happened. Often relegated to a footnote in the history of World War II, the “battle” is a prime example of what can happen when the military and civilians expect an invasion at any moment.

The first months of 1942 were strained ones for the West Coast. After the unanticipated attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 resulted in the deaths of 2,403 Americans, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt asked Congress to declare war and join the Allied Powers. At that point, Los Angeles already ranked first of all cities in America in production of aircraft, and the city’s San Pedro Bay housed an enormous naval armada. By October 1941, the shipbuilding industry in the city had jumped to 22,000 employees, up from 1,000 only two years earlier. With its vulnerable location on the Pacific Ocean, and noticeably growing manufacturing centers, Angelenos feared their city might be the next target for Japanese fleets.

“We imagined parachutes dropping. We imagined the hills of Hollywood on fire. We imagined hand-to-hand combat on Rodeo Drive,” actor and writer Buck Henry said of the tense atmosphere.

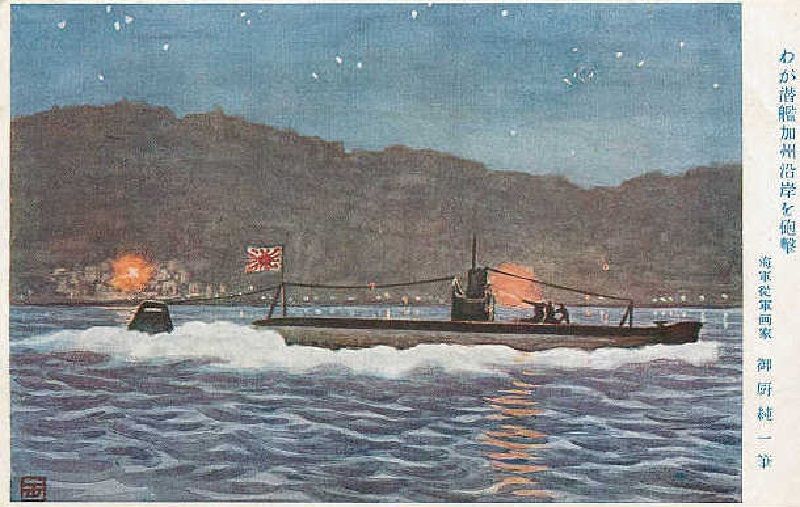

Those fears weren’t entirely unfounded. While the Japanese weren’t planning on launching an attack by air—doing so would require bringing their aircraft carriers within range of the U.S. military, risking their loss—they did send submarines. On December 23, 1941, those submarines sank the oil tanker Montebello off California’s coast, and then attacked the lumber ship SS Absaroka the very next day, causing minor damage and killing one crew member.

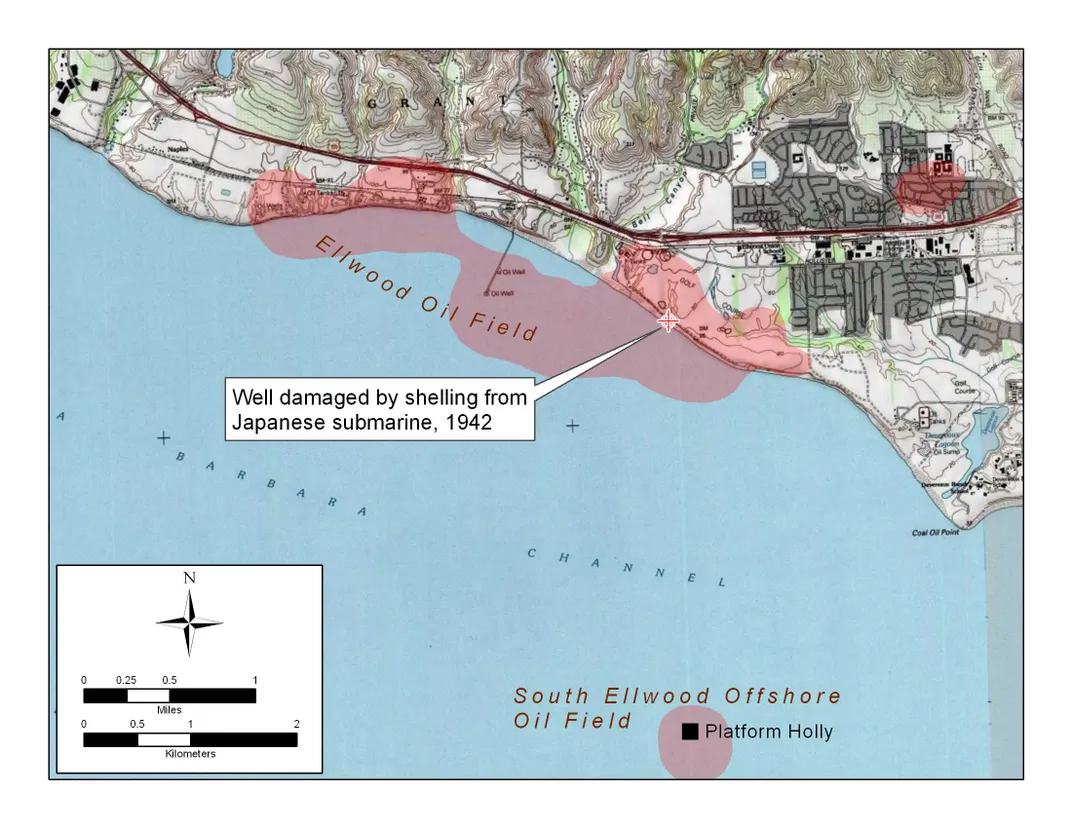

But their real coup came on February 23, when the cruiser submarine I-17, captained by Kozo Nishini, entered the Santa Barbara Channel and began firing on the Ellwood Oil Field, just 10 miles north of Santa Barbara.

“It was a real pinprick attack with highly inaccurate gunfire. They only fired between 16 and 24 shells and actually missed a very huge petrol container that would’ve caused major damage,” says historian Mark Felton, author of The Fujita Plan: Japanese Attacks on the United States & Australia During the Second World War, slated to be re-released by Thistle Publishing.

Even though the Ellwood attack caused little damage and no loss of life, it succeeded in taking a psychological toll—exactly what the Japanese intended, Felton says. “[The attack] created mass panic along the coast because for the first time the Japanese had actually physically hit the continental U.S., and that happened in the middle of the night. At this point the U.S. has no ability to send aircraft up to deal with that, because they had no radar. It gave the feeling to the American West Coast that they were highly vulnerable.”

Those jitters carried into the following days, and around 1:45 a.m. on February 25, the newly developed coastal radar picked up a blip: an unidentified aerial target 120 miles west of Los Angeles and heading straight for the city. By 2:15 two more radar sites confirmed the object, and at 2:25 the city’s air raid warning system went off. Then the shooting began.

“Residents from Santa Monica southward to Long Beach, covering a thirty-nine mile arc, watched from rooftops, hills and beaches as tracer bullets, with golden-yellowish tints, and shells like skyrockets offered the first real show of the Second World War on the United States mainland,” the New York Times reported the next day.

“I remember my mom being so nervous her teeth were chattering. It was really scary,” said Anne Ruhge to Liesl Bradner of Military History. “We thought it was another invasion.”

By 7:21 a.m. the regional warning center finally issued an all clear, and the cleanup began. The incident had indirectly resulted in five casualties, due to car accidents that happened during the blackout and heart attacks caused by shock. Anti-aircraft batteries had fired off more than 1,400 rounds, none of which hit any enemy aircraft: because there hadn’t been any enemy aircraft to begin with. The likeliest explanation for what had appeared on the radar was a stray weather balloon drifting toward land.

But in the immediate aftermath, the U.S. Navy and U.S. Army disagreed about what had actually happened, writes John Geoghegan in Operation Storm: Japan’s Top Secret Submarines and Their Plan to Change the Course of World War II. While Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson claimed as many as 15 aircraft had flown over Los Angeles, Navy Secretary Frank Knox said, “As far as I know the whole raid was a false alarm… attributed to jittery nerves.”

In the end, no trace of enemy aircraft or soldiers were ever discovered, and the military was forced to admit the “Battle” of Los Angeles was a false alarm. But it did galvanize the city and the military, says Arthur C. Verge, professor of history at El Camino College. “As bad as the Battle of Los Angeles was, I think it was a wake up call. Some people saw [the war] as far way, in the Hawaiian Islands, but now it was real, right next door.” That meant people were more willing to support the military with small actions, like rationing food or selling war bonds.

In fact, the false alarm air raid has continued to play a role in the city’s history, says Stephen Nelson, director and curator of the Fort MacArthur Museum in San Pedro. For the past 15 years, the museum has held an annual reenactment event to commemorate the Great Los Angeles Air Raid, resulting in Nelson spending years doing research for a book on the raid, which he hopes will be published sometime next year.

“We started the event because it was something unique we could do to make money. Part of the battle actually occurred on the hillside [where the museum is located] so that’s an original part of our history,” Nelson says.

In his research, Nelson spoke with 10 veterans of the war who participated in the air raid, and learned how important the incident was to them. “Almost every one of them said that’s where they got their first experience with battle conditions,” Nelson says. Even if the attack didn’t include any enemy fighters, it still felt as terrifying and important as if it had been real.

But the repercussions went far beyond the experience of air wardens pulled into action that night. This “attack” came only days after President Roosevelt’s executive order 9066—the one that authorized the internment of Japanese-Americans. Roosevelt signed it in large part due to fears that Japanese-Americans were collaborating with the Japanese military. “Prior to the raid there was a great deal of suspicion,” Felton says. “The LAPD reported that Japanese citizens had been signaling Japanese aircraft, although there’s no evidence for that.”

Lack of evidence, however, made no difference to military generals. By March 2 they had issued a public proclamation dividing California, Washington, Oregon and Arizona into two military zones, with one as a restricted zone from which all people of Japanese ancestry would soon be banned. By the end of the war, nearly 120,000 people—most of them American citizens—had been forcibly removed to internment camps across the country. The last of those camps wasn’t closed until March 1946.

“The battle has pretty much been a footnote in history, for at least my lifetime,” Nelson says. “I think it deserves more than that.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)