The Grisly History of Brooklyn’s Revolutionary War Martyrs

The Prison Ship Martyrs Monument, a crypt in Fort Greene Park, may become part of the national park system

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/b0/07b07b34-8ccf-4dd0-a028-61117b045131/8886791611_f9bfc09d0b_k.jpg)

When most Americans think of the Revolutionary War, names like Bunker Hill, Camden, Valley Forge and Brandywine come readily to mind. New York City is an afterthought—if it's part of the conversation at all. The vast arc running from Boston to Lexington, Saratoga, Philadelphia, Yorktown and south to Savannah was defined by heroics and drawn with blood. Loyalist New York caved early, and sacrificed nothing.

Or so the story goes. In reality, New York played a pivotal role in the Revolution. The war’s biggest battle—with more than 30,000 combatants, at a time when New York 's population was just 25,000—was fought not in New England or the Chesapeake but in Brooklyn. The Battle of Brooklyn was a crushing loss for the Americans, with more than 1,500 killed, wounded or captured.

George Washington's chancy nighttime retreat from Brooklyn to Manhattan was a kind of Colonial-era Dunkirk. Like the epic 1940 evacuation of German-encircled British troops from Dunkirk and other beaches in western France, Americans fled an early rout and, battle-hardened, fought on.

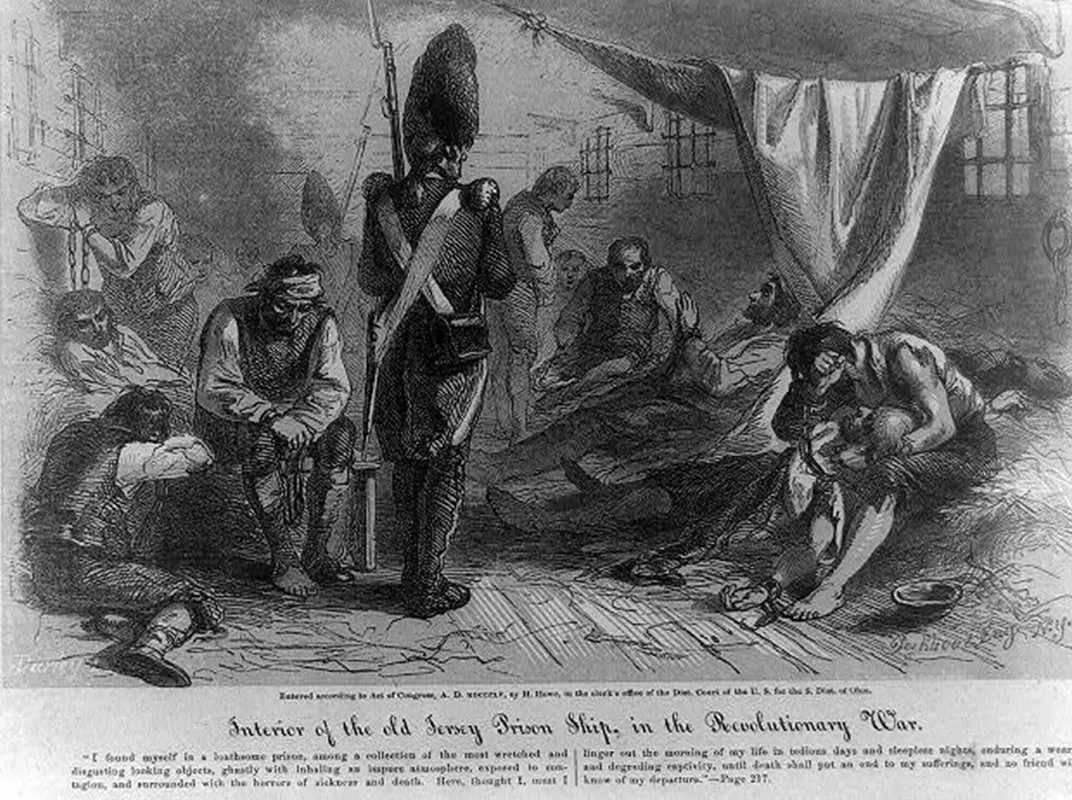

But for sheer, grinding horror, nothing approaches the suffering and sacrifice witnessed during the war aboard British prison ships. In these wet, wooden bastilles in New York waters, more Americans died than in all the battles of the Revolutionary War combined. More than 8,000 Americans died in combat between 1776 and 1783. Meanwhile, more than 11,000 prisoners died on ships anchored or, more often, aground in the East River. In those stripped-down "hulks," captured soldiers and sailors were crammed below decks in conditions that could be called bestial if the characterization wasn't an insult to wild animals.

Most of the sailors who ended up in the hulks were from privateers rather than naval vessels. America didn’t have a navy until October 1775. During the war, most of America's fighting at sea was done by private ships granted a Letter of Marque—a license, in effect, from the government authorizing American ships to attack British vessels. The private ships' owners, captains and crews stood to profit when captured enemy ships were condemned by American authorities and re-sold.

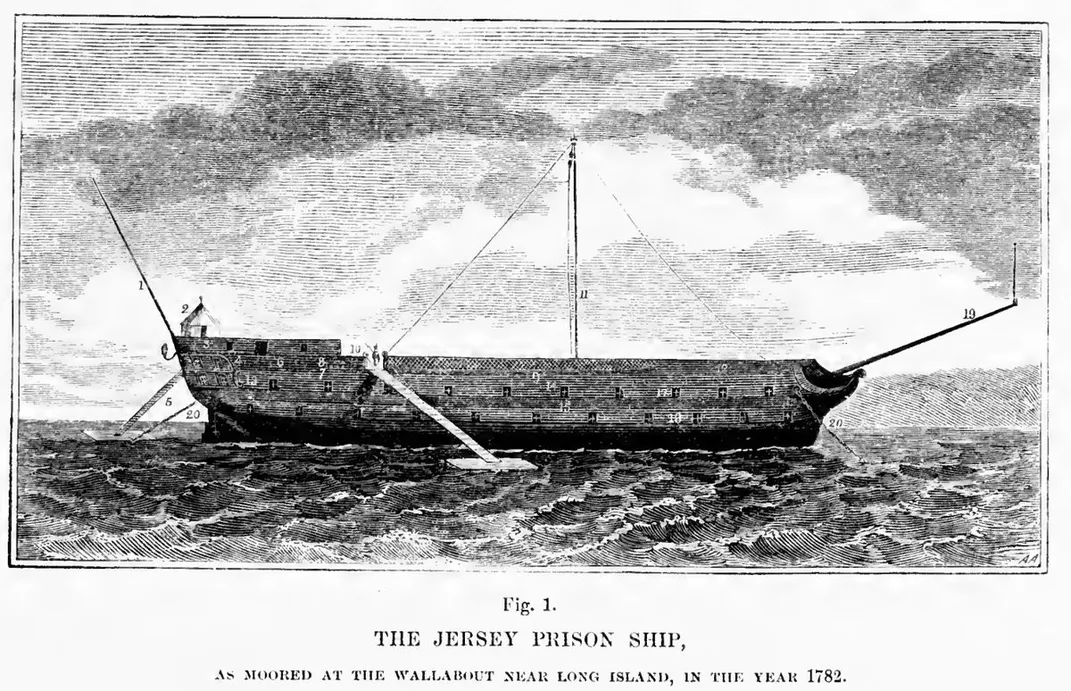

The hulks were not the only infamous prisons in use during the war: abandoned churches, "sugar houses" (or refineries) and other buildings scattered around the colonies housed prisoners in squalid conditions, while a good number of captured Americans and allied fighters were sent to England to serve time. But the tales of active brutality and lethal neglect aboard the prison ships—the notorious HMS Jersey, for example, a former 60-gun ship of the line nicknamed "Hell" by its prisoners—suggest that in those water-logged coffins, the worst nightmares of American prisoners of war came to life.

A July 1778 edition of the Connecticut Gazette, for example, recounts the experience of a Robert Sheffield, one of the few men to escape the hulks in Wallabout Bay (today the site of the Brooklyn Navy Yard).

The heat was so intense that [the 300-plus prisoners] were all naked, which also served the well to get rid of vermin, but the sick were eaten up alive. Their sickly countenances, and ghastly looks were truly horrible; some swearing and blaspheming; others crying, praying, and wringing their hands; and stalking about like ghosts; others delirious, raving and storming, all panting for breath; some dead, and corrupting. The air was so foul that at times a lamp could not be kept burning, by reason of which the bodies were not missed until they had been dead ten days. One person alone was admitted on deck at a time, after sunset, which occasioned much filth to run into the hold, and mingle with the bilge water …

Even the victuals were deadly. Prisoners were forced to subsist on moldy bread, rancid meat of suspect provenance and "soup" cooked in huge copper cauldrons with water from the East River. The East River is not a proper river at all—it’s a tidal strait. Boiled in copper, its brackish water produces something closer to a toxic sludge than food.

Every day, corpses were tossed overboard from the hulks—five to ten bodies a day from the Jersey alone. Thousands of full and partial remains eventually washed up along the Brooklyn shore. Brooklynites collected as many as they could for burial in a local tomb; eventually the remains were moved to a crypt in Fort Greene Park, about a half-mile south of Wallabout Bay.

In the early years of the 20th century, the celebrated architecture firm of McKim, Mead and White added a soaring, 149-foot Doric column, topped by an eight-ton bronze brazier, and a 100-foot wide staircase leading to the plaza above the Fort Greene crypt. In November 1908, President William Howard Taft officially dedicated the monument that exists today.

Many of the names of the thousands who died on the prison ships are known. But no one can be certain of the names associated with the crypt remains—or even how many there are. They are mingled together, bones and dust, in bluestone caskets beneath a terraced Brooklyn hill.

"These were ordinary citizens," says Brooklyn Parks Commissioner Martin "Marty" Maher, "fighting for a country that had barely been born. Every man was offered freedom if he would swear to stop fighting. But there's no record that anyone took up the offer. No prisoner renounced the revolution to gain his freedom. Not one.”

Every day, countless people fill Fort Greene Park, heading to work, walking kids to school, playing tennis, chatting on benches. It's a vibrant place that, within living memory, was largely avoided by law-abiding locals.

Like other Brooklyn neighborhoods, Fort Greene has been transformed by gentrification and other economic and cultural dynamics. The neighborhood has repeatedly reinvented itself through the years, but the 110-year-old Martyrs Monument is a reminder of a time when it was unclear if the United States would survive at all.

Now, the National Parks Service is studying this largely forgotten, grisly chapter in American history — and it could shape how future generations understand the people who are buried there. The NPS is considering the feasibility of designating the Prison Ship Martyrs Monument a unit of the national park system. The designation would be a first for Brooklyn.

"Any potential new park or monument has to meet a number of long-established criteria before the Park Service recommends that it be added to the system," says NPS community planner Amanda Jones. "If a site fails to meet just one of the criteria, we discontinue the study right there. The bar is set very high."

As it should be. And if the Park Service does decide to move forward, the Secretary of the Interior, Congress and the President all play a part in the long process, with no guarantee at the end that a park will be established at all.

For Commissioner Maher, any attention paid to the Martyrs Monument—regardless of the outcome of the NPS studies—is not only welcome, but an issue of both personal and national import. Maher oversees hundreds of parks, monuments and playgrounds from the Brooklyn Bridge to Coney Island. He can't play favorites. But when he speaks of the Martyrs Monument, his passion and his pride are palpable.

"This place is special," he says, standing just a few hundred feet from the crypt. It's a warm, late-winter morning. The monument's signature column—at one time the tallest of its kind—rises into a silvery, overcast sky. The park is alive with commuters, joggers and dogs chasing tennis balls thrown by well-caffeinated owners.

"There's a reason David McCullough said that every American should visit here," Maher says, "the same way every American should visit Arlington National Cemetery. It's sacred ground.”

For Maher, the monument commemorates a tale of bravery and resilience that few Americans learn, and that every American should know. “How can we forget what they sacrificed so that we could stand here today, as Americans?” he asks. “This is part of our legacy. In a way, it's where America began.”