In a Groundbreaking Exhibit at Mount Vernon, Slaves Speak and History Listens

Life at the home of George Washington is told anew

:focal(1050x750:1051x751)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6c/f2/6cf20d1e-93bd-4a62-be2f-67aab3277996/ct-5831_h-2445b.jpg)

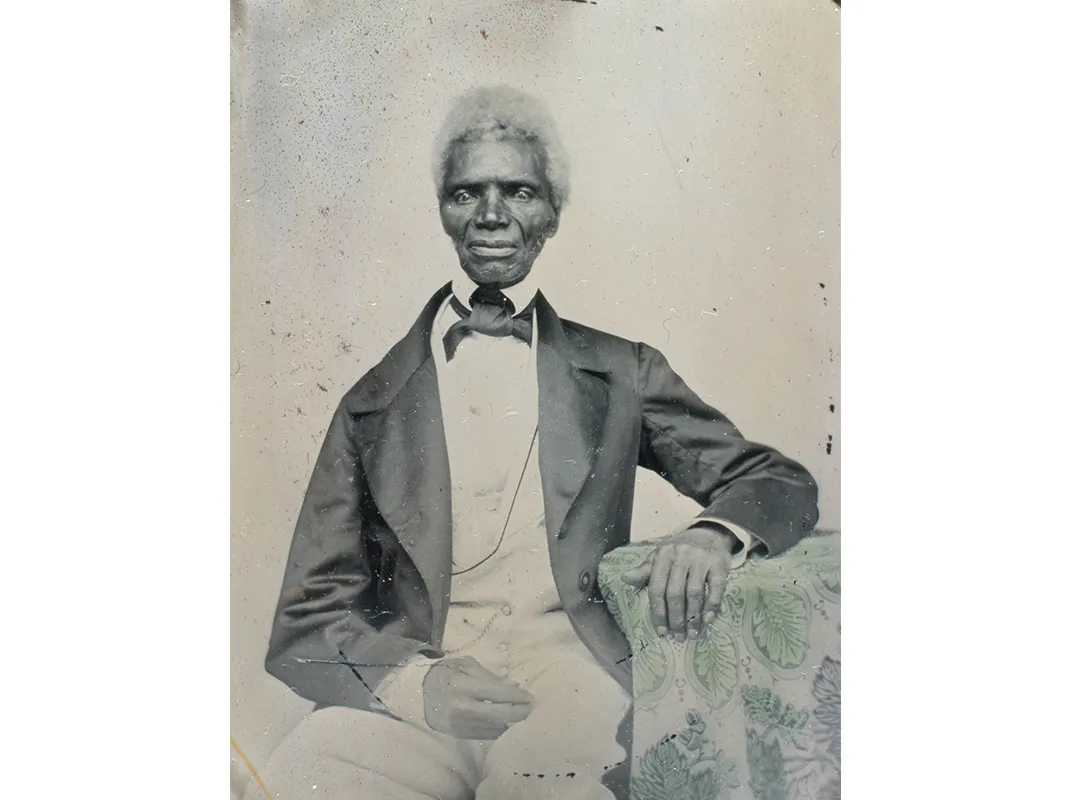

You are dining with the President. Frank Lee, standing tall in his red-and-white livery, takes your note of introduction in Mount Vernon’s entry hall. The enslaved butler chooses a spot for you to wait–either in the elegant, robin’s egg blue front parlor, or in the cozier “little parlor”–while he alerts George Washington and wife Martha to your arrival.

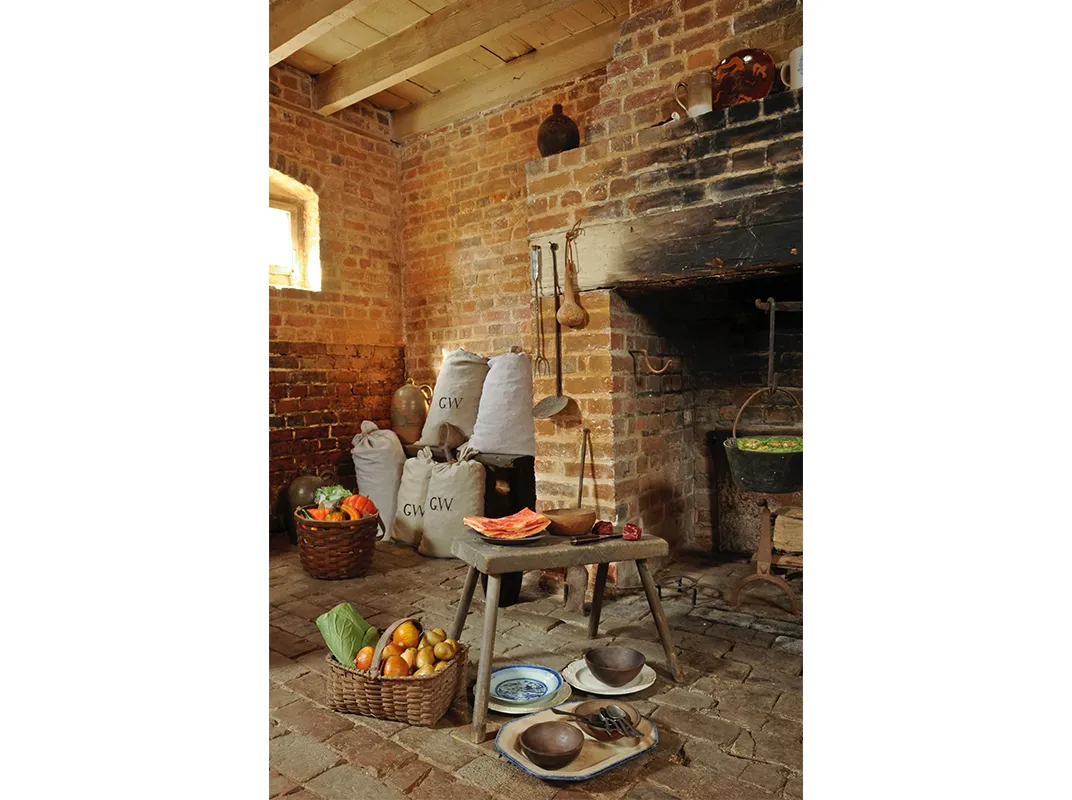

As the opal haze of a July afternoon rolls off the nearby Potomac River, Lee’s wife, Lucy, labors alongside another enslaved cook, Hercules, to ready dishes for the 3:30 p.m. dinner. Frank, with the aid of waiters Marcus and Christopher Sheels, serves your meal. Around 6 o’clock, they wheel out a silver hot-water urn, and you adjourn to the portico for coffee, tea and conversation with the first family.

Above, in a guestroom, enslaved housemaids, like seamstresses Caroline Branham and Charlotte, go about the last tasks of a day begun at dawn. They carry up fresh linens and refill water jugs. Mount Vernon’s enslaved grooms make a last check on the horses.

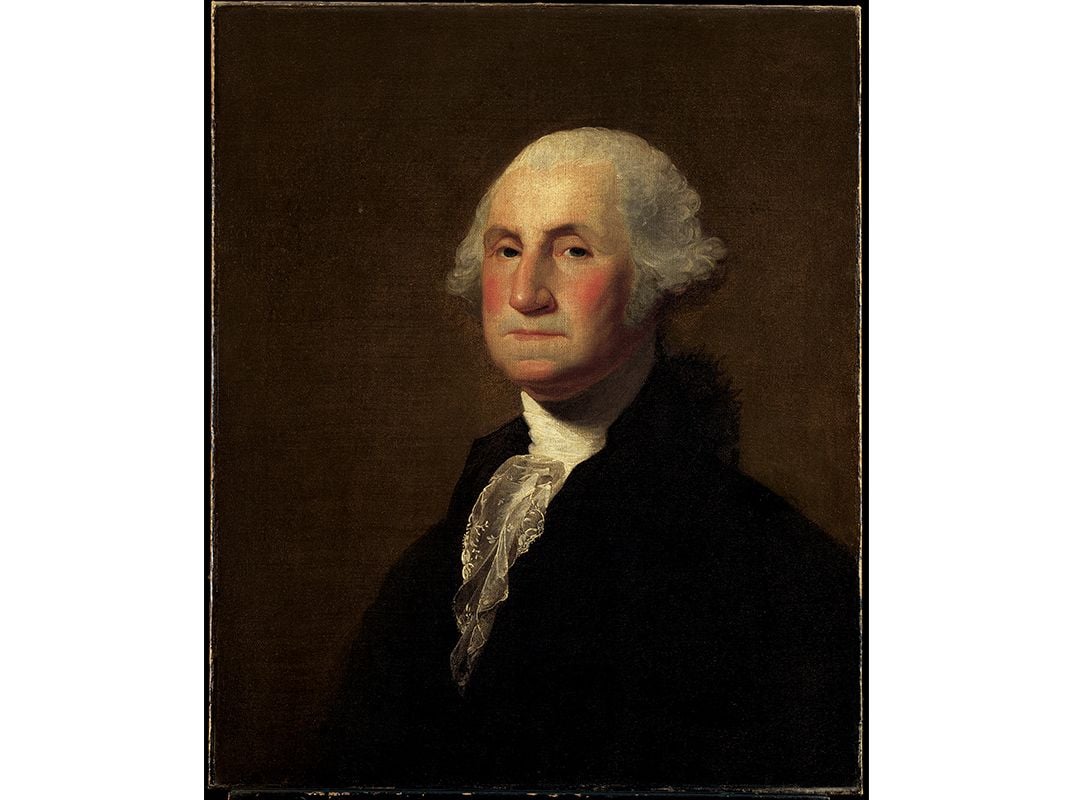

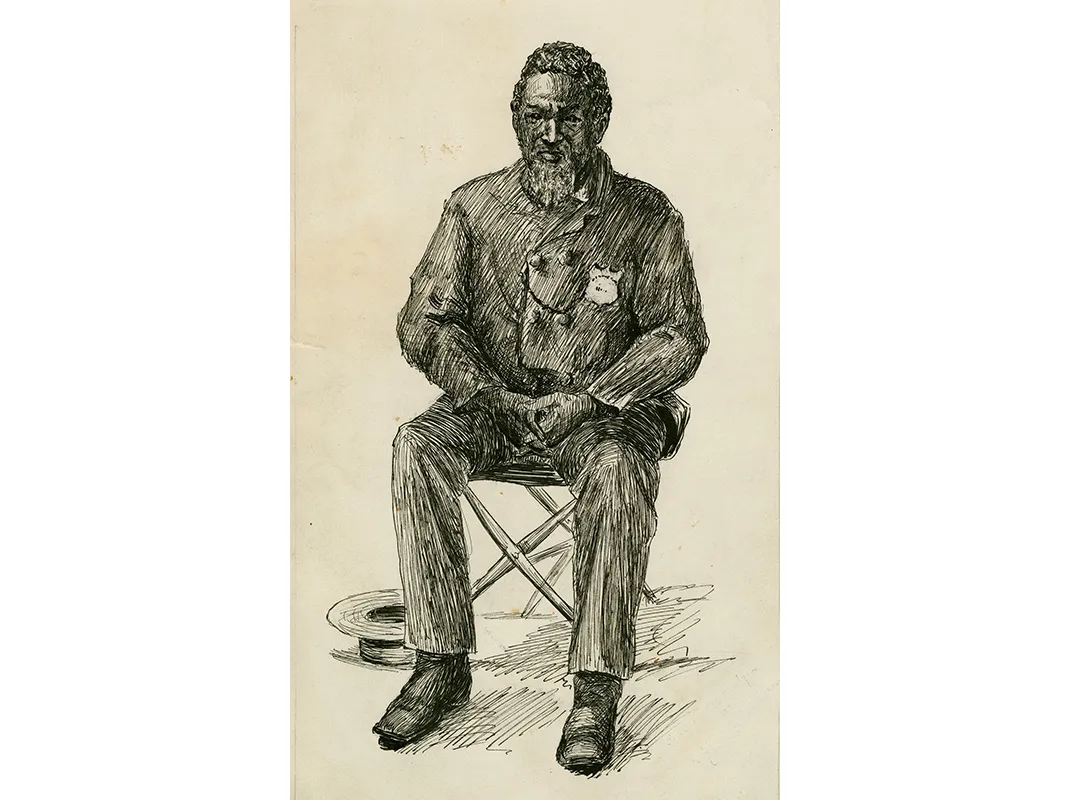

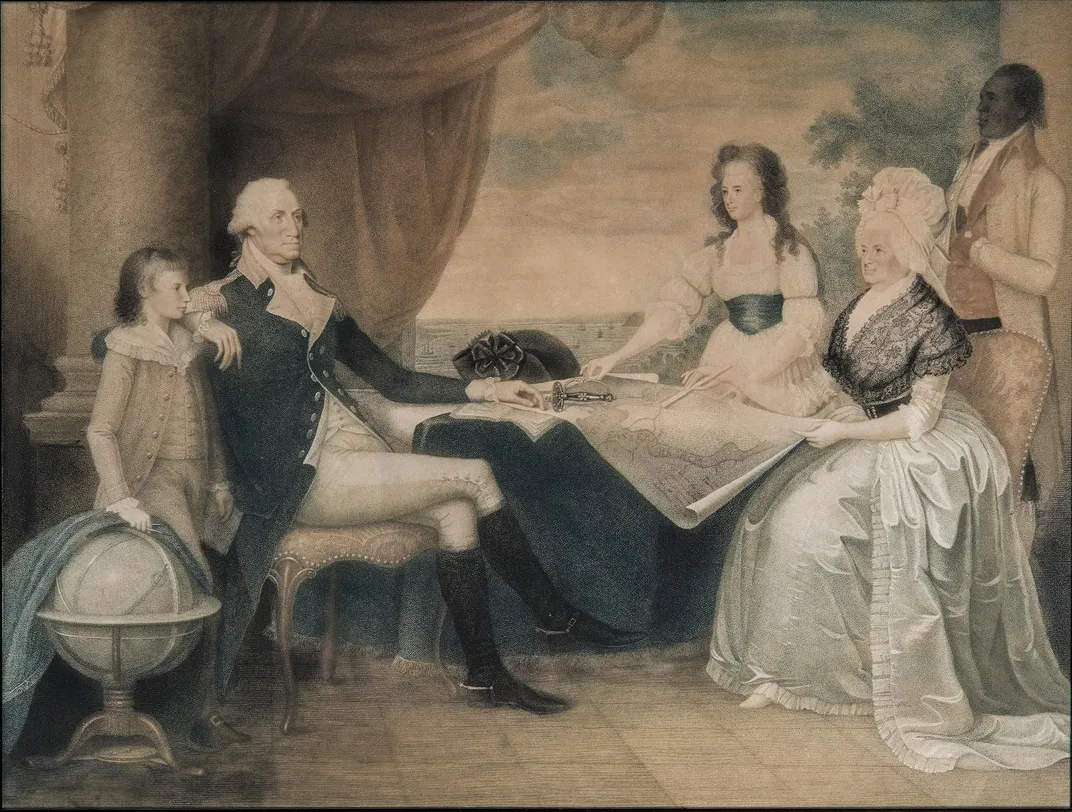

This was how English architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe likely experienced his July 16, 1796 visit to Washington’s estate. During his stay, he sketched the grounds and the people with customary fervor. In Latrobe’s first draft of a painting of his day with President Washington, the silhouette of an enslaved man (possibly Frank Lee) was part of the picture. But in the finished watercolor, he is gone.

Lives Bound Together: Slavery at George Washington’s Mount Vernon, a new exhibit at the Virginia estate, on view through 2018, brings Frank, Hercules, Lucy, and other slaves at Mount Vernon to the fore. It’s a project that has been many years in the making. “Our goal was to humanize people,” says Susan P. Schoelwer, Mount Vernon’s Robert H. Smith Senior Curator. “We think of them as individual lives with human dignity.”

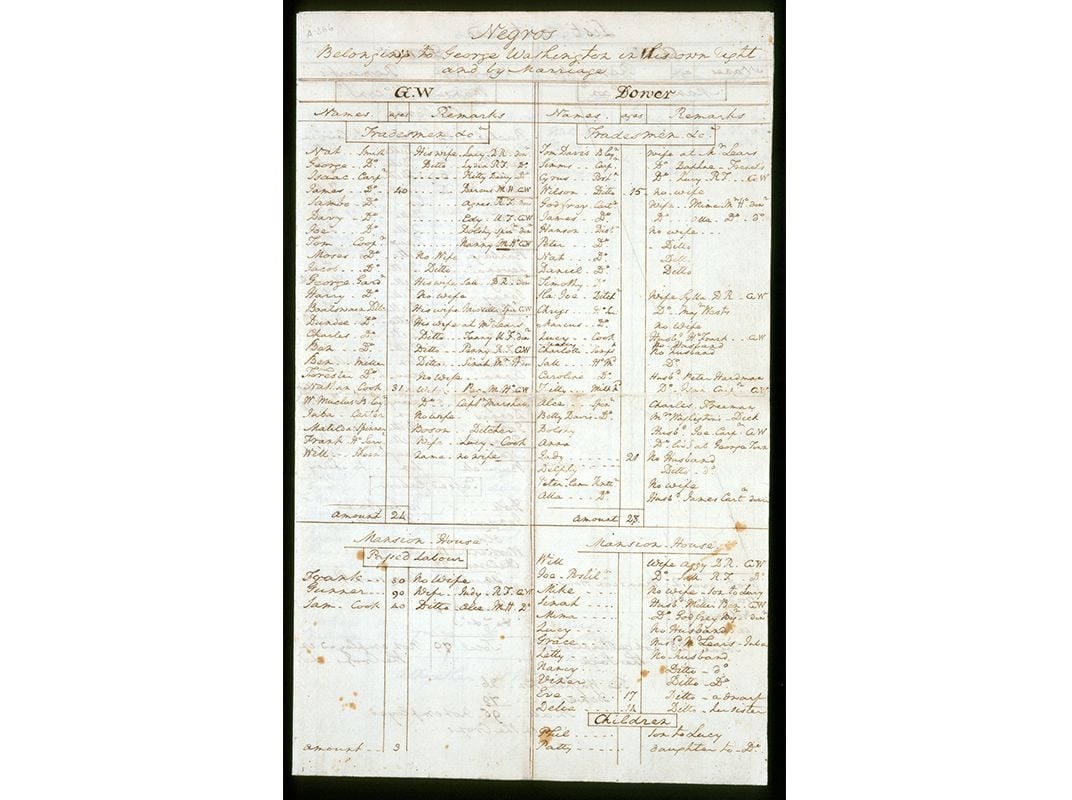

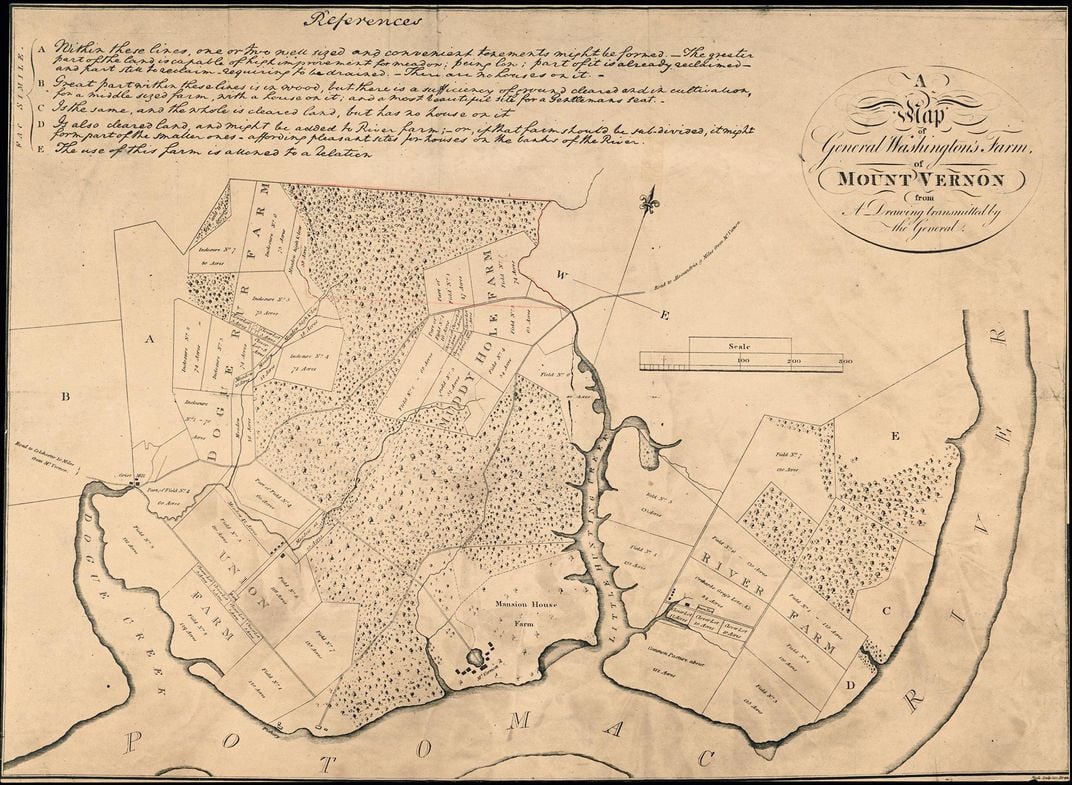

The exhibition centers on 19 of the 317 enslaved individuals who worked and lived at Mount Vernon during the Washingtons’ lifetime. Mining a rare cache of material culture, artwork, farm tools and plantation records, curators partnered with scholars and descendants of the enslaved to retell their shared past through the stuff of everyday life.

“I know that they are speaking again,” says descendant Judge Rohulamin Quander, a member of one of the oldest traceable African-American families in the United States. “Those voices were unsung up until 1799, and we don’t have any pictures or voice recordings of what they had to say. But they have reached out beyond the grave and said to each of us, we’re depending upon you. You have to do this for us.”

In his 1799 will, Washington included a slave census and a directive to emancipate his slaves. His decision to do so–which Martha promptly carried out–reflects the nearly seven decades the President spent thinking about slavery’s effects on farming and families. Boldly, Lives Bound Together raises a thorny set of questions: What sort of slave owner was Washington? How and why did his thoughts on slavery change?

Records show that George, a slave owner since age 11, brought fewer slaves to his 1759 marriage than Martha. Visitors to Mount Vernon left behind conflicting accounts of Washington’s treatment of his slaves. Whippings and hard labor were frequent forms of reprimand. Yet Washington depended on the enslaved population to take care of his family and secure plantation profits as he took on military and political duties. Often written far from home, some of Washington’s most fascinating correspondence was not with other “founders” but with his farm managers. On New Years’ Day 1789, for example, as the new federal government began to take real shape, Washington turned his attention to Mount Vernon’s needs. He wrote one overseer with clear instructions:

“To request that my people may be at their work as soon as it is light—work ’till it is dark—and be diligent while they are at it can hardly be necessary, because the propriety of it must strike every manager who attends to my interest, or regards his own Character—and who on reflection, must be convinced that lost labour can never be regained—the presumption being, that, every labourer (male or female) does as much in the 24 hours as their strength, without endangering their health, or constitution, will allow of.”

Despite his mounting responsibilities on the national stage, Washington remained a shrewd businessman. He relied on slaves to keep his Virginia plantation running at a profit, says David Hoth, senior editor at The Papers of George Washington editorial project. “He was inclined to suspect his workers of malingering and petty theft, perhaps because he recognized that they probably saw slavery as an unnatural and unpleasant condition,” says Hoth. “He sold at least one runaway to the West Indies and threatened others.”

In private, the president came to support gradual abolition by legislative act and favored measures, like non-importation, that might hasten the change. He pursued Mount Vernon’s runaway slaves, albeit quietly, without using newspaper advertisements. By 1792-93, according to Hoth, George Washington began to mull the idea of emancipation.

“It’s important to tell the story of his views on slavery and how they evolved,” says Schoelwer. “He was in the position of trying to balance private concerns with his public commitment to the survival of the nation.” At the same time, he used legal loopholes to make sure his slaves were kept enslaved.

The Mount Vernon exhibit collects a diverse medley of African-American sagas that reconsider the 18th-century world’s understanding of slavery and freedom. Via short biographies, reinterpreted artifacts, and new archeological evidence from Mount Vernon’s slave cemetery, 19 lives emerge for new study. A new digital resource, an ever-evolving slavery database, allows visitors to search Mount Vernon’s enslaved community by name, skill or date range.

So far, the database has gathered information on 577 unique individuals who lived or worked at Mount Vernon up to 1799, and compiled details on the more than 900 enslaved individuals with whom George Washington interacted during his travels, according to Jessie MacLeod, associate curator at Mount Vernon. But though it shows a thriving plantation, the database also tells a different story. “You really get a sense for how often people are running away,” says MacLeod . “There are casual mentions in the weekly reports, of people being absent sometimes for 3 or 4 days. It’s not always clear whether they came back voluntarily or were captured. There’s no newspaper ad, but we do see an ongoing resistance in terms of absenteeism, and when they’re visiting family or friends in neighboring plantations.”

In the museum world, reinterpretation of slavery and freedom has gained new momentum. Mount Vernon’s “Lives Bound Together” exhibit reflects historic sites’ turn to focus on the experience of the enslaved, while exploring the paradox of liberty and slavery in daily life. In recent years, historians at Mount Vernon, along with those at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and James Madison’s Montpelier, have rethought how to present those stories to the public through new signage, “slave life” walking tours, and open archeological digs. A series of scholarly conferences--sponsored by institutions like the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the University of Virginia, and many more--have been hosted at the former presidential homes.

Latrobe’s portrait of life at Mount Vernon may have initially included the slaves who made Washington’s estate hum, but the finished painting only tells part of that story, Lives Bound Together completes the picture by depicting the shared journey of the Washingtons and the enslaved. “We helped build this place and make it what it is. We helped make the president who he was,” says Shawn Costley, a descendant of Davy and Edy Jones, in the exhibit’s film. “We might not have had voting power and all that back then, but we made that man, we made George Washington, or added to or contributed to him being the prominent person that he is today.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/georgini.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/georgini.png)