This London Building Tells the Story of a Century’s Worth of Disease and Epidemics

In the borough of Hackney, a ‘disinfecting station’ ostensibly kept the public safe from the spread of infectious illness

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/21/22/2122c946-450e-4e81-bf2b-808af1baf854/h-pd-5-1-2_b.jpg)

Coming down with an infectious disease in early 1900s London would have been a pretty unsettling experience. Not only were effective treatments hard to come by, but the municipality had the legal right to enter your home and disinfect it. City workers could seize your belongings and take them away for steam cleaning, all in the name of public health. Yet these precautions were not draconian or even heartless: If this process rendered you homeless, you would be offered overnight accommodation in a comfortable, modern one-bedroom apartment alongside the building where your possessions were being sanitized.

Measures to contain today’s pandemic, such as stay-at-home orders and compulsory mask wearing, may feel to some like an unwelcome intrusion by the state into their daily lives. At the Hackney Borough Council Disinfecting Station, however, anti-disease actions were more of a public amenity, a way to keep the public healthy and a cohesive unit

The local government that oversaw the disinfecting station, the Metropolitan Borough of Hackney (MBH) in northeast London, came into being in 1899 as part of the London Government Act. The culmination of a series of legislative changes that began in 1855, the law brought a major reorganization and standardization to local government in the British capital. Formerly a civic parish in Middlesex, a county bordering the City of London (an area with its own jurisdiction), Hackney’s ancient boundaries did not change much when it became a metropolitan borough of the new ‘County of London’. But the way the area was governed did, reflecting the expansion of the capital into what were once its leafy suburbs.

Home to a largely working-class population living in often terribly overcrowded dwellings, Hackney was subject during this period to frequent outbreaks of infectious diseases such as smallpox, diphtheria, scarlet fever, measles and whooping cough. Though public health outcomes were much improved by 19th-century investment in sanitation infrastructure and hygiene procedures, Britons were still dying from infectious diseases in high numbers, with children at particular risk. In 1899, the year the MBH was created, 116 Hackney residents died of the measles, 115 of them children under the age of 15. All 47 of the borough’s whooping cough deaths were in children, and a further 252 died from diphtheria. Infant mortality (deaths of children under the age of 1) was 165 per 1,000 live births. To put this context, in 2018, the figure was 4 per 1,000.

“If you survived, it was very common for you to have had at least one of those diseases in your childhood. And as much as the mortality that's important, it's also the morbidity. There was a lot of sickness around,” says Graham Mooney, a historian of medicine at Johns Hopkins University. “They were fairly common diseases but it doesn't mean to say they weren't devastating, or they didn't actually have a big emotional and practical toll on people's lives, because they did.”

Local authorities had been disinfecting domestic premises and articles of clothing and bedding in England since at least 1866, when the government introduced a law that required them to administer disinfection equipment. The practice was widespread across the country but provisions varied widely and Hackney’s operation was a modest one. By 1892, a municipal sanitary committee denounced it as “thoroughly and dangerously inefficient for the requirements of the District.”

A dedicated facility opened in 1893, complete with modern steam disinfecting equipment, but Hackney’s medical officer for health, John King Warry, didn’t stop there. Backed up by new national legislation that permitted his team to spend what it liked to cleanse people and premises “infested with vermin”, he campaigned for the creation of a state-of-the-art disinfecting and disinfesting station that included accommodation for whoever required it.

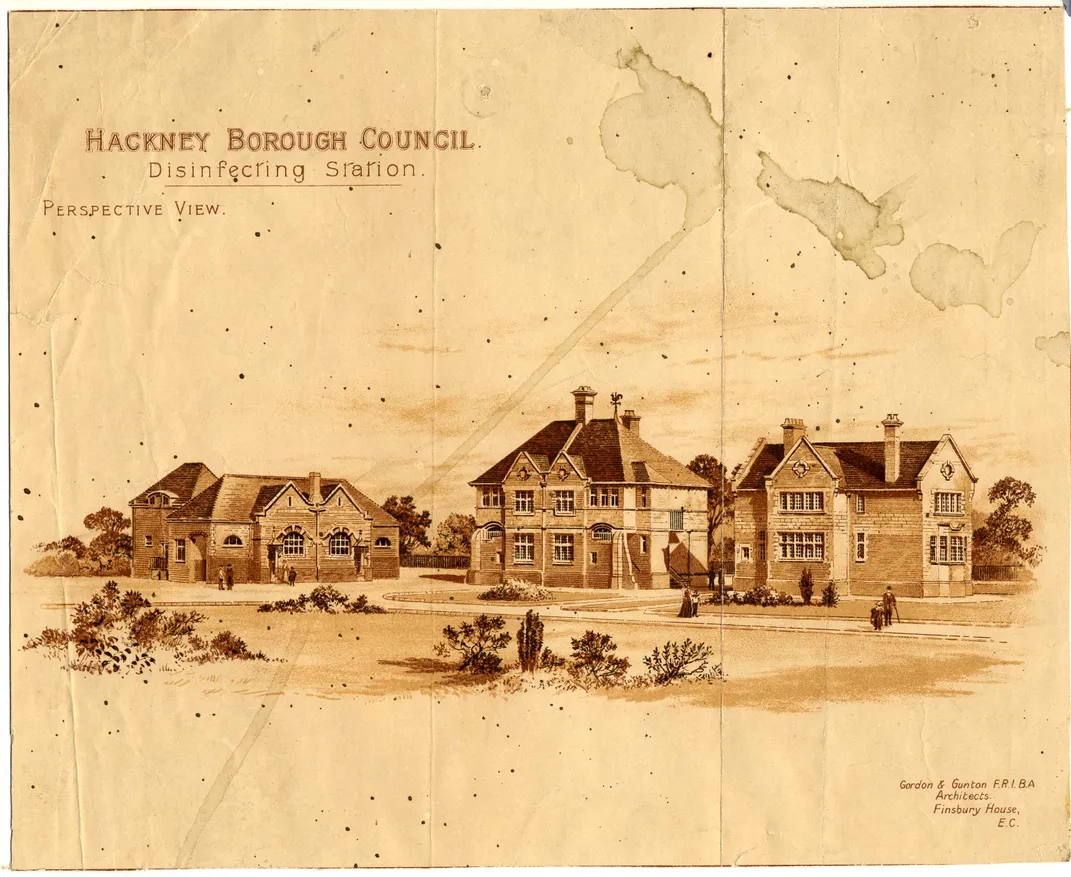

The result of King Warry’s efforts, a three-building complex completed in 1901 at a cost of just under £10,000 (around £1.25 million today), was used for decades. A groundplan of the building held by Hackney Archives, the official repository for the historic records of the MBH and its successor, Hackney London Borough Council, shows ‘Infected’ and ‘Disinfected’ rooms connected by a large boiler, a workshop, bathrooms for men and women, a laundry, ironing room and drying room, as well as stables and cart sheds. Infected people and their possessions would enter the station from one side, move through the process of steam disinfection and exit out the other side. Metal hoppers in which people would have placed their infested clothes before taking a sulphur bath to treat their scabies could be found in the men’s and women’s bathrooms.

“One of the concerns was that if people were ill with infection, in order to make sure that they didn't pass on the infection, cleaning and disinfecting and cleansing, both where they lived, and the things that they owned and had contact with, was a way of eradicating germs,” says Mooney.

“So a lot of health authorities, as well as having isolation hospitals, they would build these disinfection stations that perform that disinfecting ritual. These sorts of places were really common and they were a very important part of how Victorian and Edwardian local authorities responded to outbreaks,” he adds.

Changes to the station over the years track advances in public health strategy.

Sending teams of government employees out to disinfect and disinfest homes across the borough was always a significant part of local medical officers’ work. In 1902, the station’s first full year of its operation, 2,838 rooms were fumigated, with 1,009 of these having their walls stripped of paper and washed with carbolic solution. That same year, 24,226 articles of furniture, bedding and clothing were disinfected at the station, all according to the annual report of Hackney’s health department, available online as part of the digital archives of the Wellcome Collection.

The shelter house itself was little used, despite the busyness of the rest of the complex. In 1902, only 97 people stayed overnight, and by 1905 the borough was having to advertise the existence of the apartments. From the 1930s onward, demand was so low that the shelter house was turned into staff accommodation for people working in the department of the medical officer of health. In all likelihood, says Tim Walder, a conservation and design officer at Hackney Council, who studied the station in 2015, its schedule of disinfection and disinfestation rendered overnight stays mostly unnecessary. After all, even the most comprehensive fumigation process only takes a couple of hours.

One might expect the station to have been in greater demand than usual during the 1918 flu pandemic, but this was not the case. Though 698 people died of flu in Hackney that year, up from just 28 in 1917, the number of rooms fumigated and items disinfected actually fell, from 1,988 and 12,626 respectively in 1917 to 1,347 and 11,491 the following year. The reason interventions by the station fell rather than rose, suggests Andrea Tanner in her article “The Spanish Lady Comes to London: the Influenza Pandemic 1918–1919,” is that the government of the day encouraged local authorities to “concentrate their activities on providing nursing services and home helps” rather than disinfection measures. It did so, Tanner suggests, because experience from the prior flu pandemic of 1889-92 showed that sanitary measures were largely ineffective. In addition to that, the war effort meant that many of the staff that would have been required for disinfection had been called up for military or civilian service.

In the 1930s, as infectious diseases became less virulent and more treatable thanks to a combination of vaccines and antibiotics, the complex shifted to house citizens displaced by clearing out slums. A film produced by the borough’s public health department in 1935 on its slum clearance and re-housing program shows tightly packed terraces of run-down homes with rickety rear additions and broken windows and fences. Inside, rooms are narrow and low ceilinged, and mold proliferates. Later in the film, footage reveals the new apartment blocks that the local authority built to replace the slums: Towering above the older housing stock around them, they are tidy, with large windows and balconies.

“You were removed from your slum, which the council was demolishing to build lovely new [government] housing, and they wanted to make sure that you didn't take your vermin with you,” says Walder. In 1934, the local authority built a drive-in fumigation and airing shed at the Hackney station with a capacity of 3,400 cubic feet, large enough to fit an entire removal truck containing the “holding the effects of one to three families”, according to the 1936 report. Fitted with an enormous sliding door lined with zinc, the chamber had a roof of reinforced concrete covered with asphalt.

The shed still survives today, its utilitarian design at odds with the pleasing aesthetics of the earlier architecture. It’s here where the story takes on a disquieting tone. Large enough to disinfest entire trucks loaded up with furniture, the sheds used Zyklon B to produce hydrogen cyanide gas, the same chemical used by the Nazis in their death camps. As Walder wrote in his report on the building, “the use of Zyklon B in 1930s Hackney was for genuine, if paternalistic, public health reasons (to destroy vermin).

“This innocent use of the chemical was widespread on contemporary continental Europe. The evil came when this innocent use was perverted for sinister purposes through a political process which equated certain groups of people with vermin.”

The disinfecting station’s other roles over the years included disinfecting library books (as many as 4,348 a year in the 1960s) to help prevent outbreaks of disease between households and, during World War II, treating civil defense personnel suffering with scabies.

The station continued operations until 1984, disinfecting second-hand clothing prior to export sales abroad on the one hand, and treating headlice on the other. Its decline was inevitable, says Martin Gorsky, a professor in the history of public health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, a consequence of vastly improved health outcomes—“vaccines were in, infant mortality was solved”—and the founding of the National Health Service in 1948, which took power away from local authorities. “The modern safe public health hygienic environment was in place,” he says.

Today, it can be found tucked between a waste depot and an electricity substation close to Hackney’s eastern boundary. Out of use since the mid-1980s, the “rare and complete survival of a purpose-built disinfecting station” has long been deemed at-risk by Historic England, the public body charged with protecting the country’s historic buildings.

Walder was asked to report on the state of the disinfecting station soon after taking on the role of principal conservation and design officer for Hackney Council. “Some of the doors hadn't been opened for a very long time. I had to get a man with a crowbar to open some of them,” says Walder.

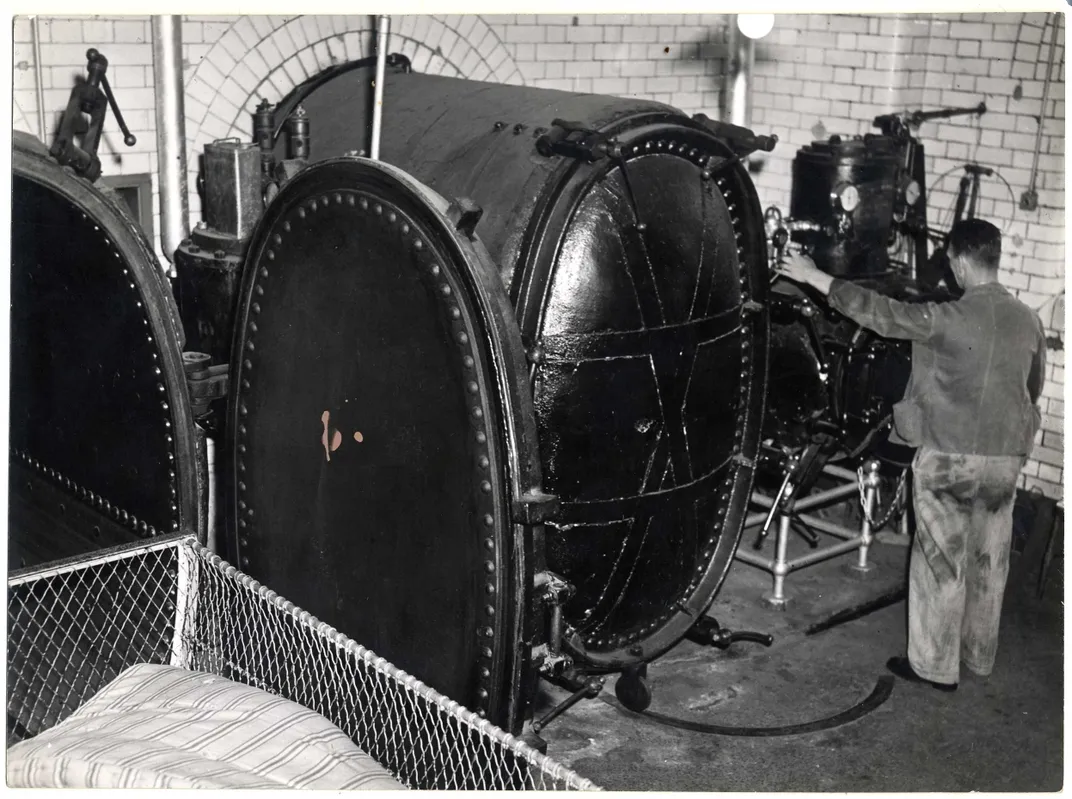

As Walder wandered through the loosely Arts and Crafts-style building, he came upon disinfection and fumigation machinery dating from throughout the life of the station. A control panel located between two disinfectors bears a plaque from an engineering company more than 120 miles away in Nottingham.

It took quite some time to get to the bottom of it all, he says. “Some of it was old and we didn't really know what we were looking at. Also the building's been altered - it wasn't always clear what was original or later, what was interesting and what was less interesting.”

Walder pieced it together after poring over documents held by Hackney Archives, Wellcome Collection, London Metropolitan Archives and the library of the Royal Institute of British Architects, as well as consulting with experts at groups including Historic England, the Victorian Society and the Greater London Industrial Archaeology Society.

Across the yard from the station sit a three-bedroom Caretaker’s Lodge and a Shelter House, which comprises four almost identical one-bedroom apartments. Now the headquarters of a literacy charity and home to live-in guardians, respectively, these buildings remained in fairly good condition.

The same can’t be said of the disinfectant station itself, unfortunately, unsurprising given that it had been out of use for nearly 40 years. That said, the scale and ambition of the place are still clear to see. Compared to other disinfecting stations built during this period, mostly alongside hospitals, orphanages and the like (none of which survive today, as far as Walder can gather), the Hackney site was “particularly big and elaborate and expensive”, says the officer.

“You might expect something industrial and plain but it's not: it's got ornamental leadwork and rather fancy Portland stone,” says Walder.

In the fall of 2020, Hackney Council announced, based on Walder’s report, that it would be mothballing the station in the hope of safeguarding it for the future. The roof and guttering will be repaired to stop any more water getting in, the windows and doors will be boarded up and any internal pipes that once held noxious chemicals will be drained.

Walder’s hunch is that the site was a “prestige project” for the borough, “a kind of municipal showing off” in the form of what looks to be the first public building built since creation of the MBH in 1899. King Warry’s annual report for 1900, in which he states that, “Hackney will be the most completely equipped district in London for dealing with infectious and contagious disease,” certainly supports Walder’s theory.

“Public health, because it was part of local governments, became part of local government politics as well,” says Gorsky. “It was an area of tax and spend. There were things that were put on the agenda because electorates might like them.”

Grand public baths, for people who didn’t have bathing facilities at home, were another example of this type of spending by municipalities serving economically disadvantaged communities, adds Gorsky. The Hackney Disinfecting Station would have served a similar purpose.

Walder would one day like to see the Disinfecting Station turned into workshops or offices, along with a foyer display to illustrate the history of the site. “I can't see a situation where it became the National Museum of Disinfecting Stations because there's only one and it's in such an out of the way place,” he adds with a smile.

When Walder was writing his report on the building for the council, he recalls that “it felt terribly abstract, like something from another age.” The events of the last year have changed all that: “Now it really feels close to home.”