The Hammond Train Wreck of 1918 Killed Scores of Circus Performers

One hundred years ago, a horrific railway disaster decimated the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus—but the show still went on

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/29/ef/29ef1c75-a0e1-4f0f-865a-c9037a00e764/hammond_circus_train_wreck_1918.jpg)

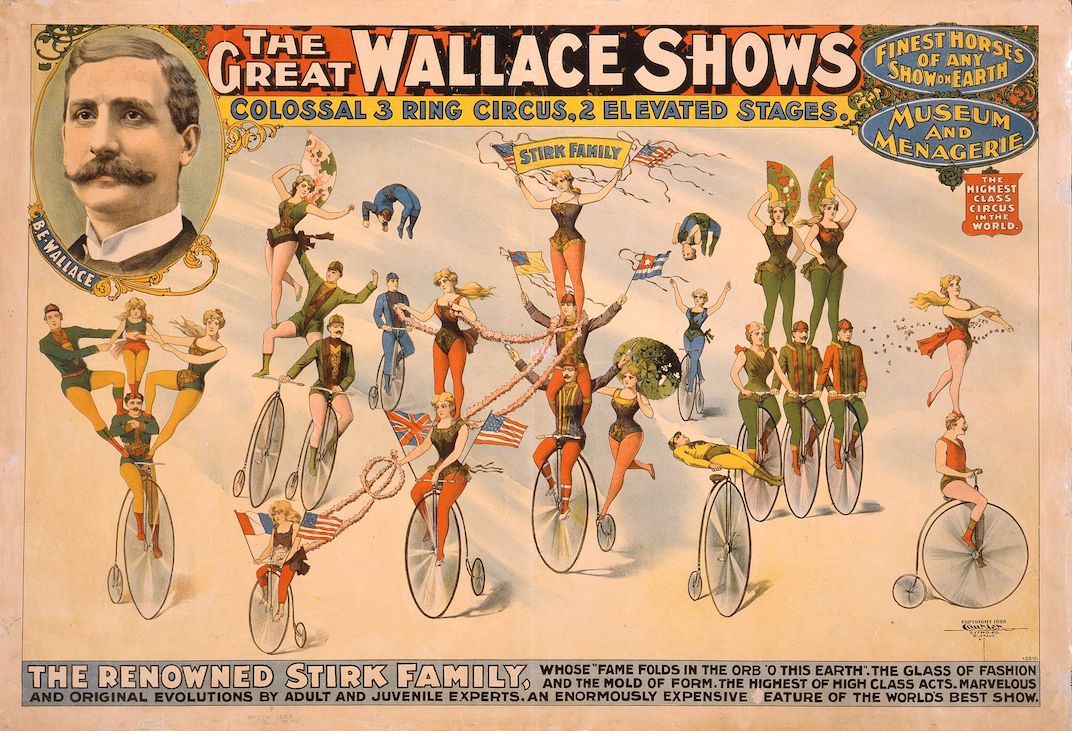

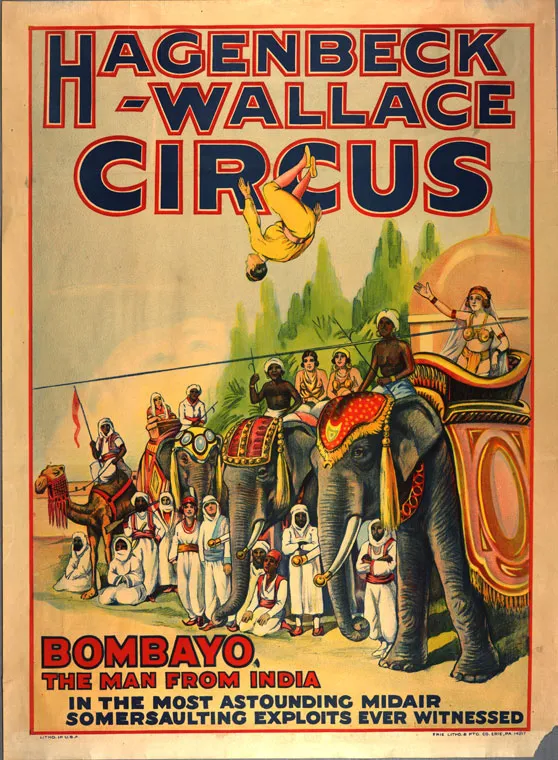

The Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus wasn’t the largest show in the country—but it came close. By 1918, the company employed around 250 performers, from acrobats to equestriennes, clowns to lion tamers. Formed in 1907 when circus owner Benjamin Wallace purchased the Carl Hagenbeck Circus, the outfit had since grown to be a $1 million extravaganza that required two separate trains of 28 cars each to transport all the performers, animals, costumes and gear across the country.

In fact, it was trains that made such an enterprise possible. “The enormous growth of railroads in the post-Civil War ear fueled the golden age of circuses,” writes historian Douglas Wissing. “Instead of plodding through the mud at ten miles a day from small town to small town, circuses hitched their railcars to trains and clattered to cities hundreds of miles apart overnight.” By the turn of the 20th century, nearly 100 circuses roamed the United States, more than a third of them traveling by rail. Circuses were an unmatched spectacle, bringing together a nation rapidly filling with new immigrants from different cultures and backgrounds. As cultural historian Rodney Huey writes, “The day the circus came to town was a holiday, disrupting the daily lives of its citizens, often to the point that stores closed, factories shut down and school classes were dismissed.”

As for the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus, it was the nation’s third-largest circus, and considered the Midwestern version of the East Coast P.T. Barnum show. When the Hagenbeck-Wallace show came to town, visitors could expect some of the most superbly trained animals, renowned trapeze artists, and breathtaking equestrian routines.

Of course, traveling by train came with its own risks. Railroad accidents of the era were common, and deadly. In 1892, when the circus was simply the Great Wallace Show, a railroad wreck resulted in 26 trained horses being killed. A second in 1903 occurred with the second train didn’t slow down on its approach into the yard, and slammed into the train ahead of it, killing 26 men and several animals, writes Richard Lytle in The Great Circus Train Wreck of 1918.

But neither of those earlier accidents compared to the scale of the disaster the Hagenbeck-Wallace team on June 22, 1918.

The circus had just completed two performances in Michigan City, Indiana, and was traveling overnight the 45 miles to nearby Hammond. The first train, carrying workers and many of the circus animals, cruised on to its destination with no problems. But engineers on the second train halted their progress to fix a hotbox. The overheated axle bearing could cause a fire on the train if not deal with immediately.

It was around 4 a.m. when the second train pulled off onto a side track, but the last five cars— including four wooden sleeper cars—remained on the main track. As the engineers worked, and the performers slept, an empty train used to transport soldiers to the East Coast for subsequent deployment to the warfront in Europe came barreling down the main track. The driver blew past several stop signals, and then the lamps of several of the circus engineers trying desperately to stop the oncoming train.

But the train’s steel-frame Pullman cars smashed into the wooden circus coaches, at speeds between 25 and 60 miles per hour, according to contemporaneous newspaper reports. The sound of the collision was so loud that nearby farmers awoke and hurried to see what had happened.

Henry Miller, the assistant light manager, was among the survivors thrown from the wreckage with minor injuries. “I was in the last coach, next to the caboose, and was asleep when we were hit,” he told the Chicago Daily Tribune a day after the accident. “I woke to the sound of splintering wood…Then there was another crash, and another, and another… The train buckled on itself. It parted in the center as clean as thought it had been sliced with a giant knife.”

How many people were killed or injured from the collision is impossible to say; in the moments after impact, the kerosene lamps that hung in the hallways of the wooden cars quickly set everything aflame. Survivors clawed their way out of the debris or called for help before the fire engulfed them. Acrobat Eugene Enos, trapped beneath some wooden beams, received aid from his wife, Mary, and Lon Moore, a clown. “We pulled him clear just as the flames licked at him,” Mary later told the Chicago Daily Tribune.

But most weren’t so lucky. The fire spread so quickly that crash survivors risked their own lives to pull friends and family out of the wreckage. Although the Gary and Hammond fire departments arrived as quickly as possible, the only source of water were nearby shallow marshes. A wrecking crane was also brought to the accident site to dig people out, but couldn’t initially be used because the heat from the fire was too intense. The Daily Gate City and Constitution-Democrat, an Iowa newspaper, wrote later that day, “The task of identifying the dead and seriously injured was almost hopeless. Not only were many of the bodies burned so badly that recognition was impossible, but practically everyone on the train was killed or hurt.”

More than 100 people were injured in the accident, and 86 were killed, including some of the circus’s famed performers: animal trainer Millie Jewel, dubbed “The Girl Without Fear”; Jennie Ward Todd, an aerialist and member of the Flying Wards; bareback rider Louise Cottrell and Wild West rider Verna Connor; strongmen brothers Arthur and Joseph Dericks; and the wife and two young sons of chief clown Joseph Coyle.

In the aftermath of the accident, the families of the deceased performers struggled with who to blame. The railway company? The engineer driving the empty train, a man named Alonzo Sargent, who was arrested and charged with manslaughter? The circus company itself? All of them seemed to shirk any blame. One spokesperson for the Interstate Commerce Commission even released a statement to the Chicago Daily Tribune, saying, “We do everything we can to discourage the use of wooden cars on passenger trains and urge the substitution of steel ones. That is all we can do.”

As for the survivors, they decided the show must go on. Despite the tremendous physical and psychological toll of the accident, the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus only missed two performances, thanks to other circuses providing equipment and crew.

In the following weeks, 53 of the deceased performers were offered a burial in a large plot at Woodlawn Cemetery in Chicago, which had just been purchased by the Showmen’s League, a fraternal order created in 1913 to support men and women in show business. Only five victims had marked graves; the rest were burned too badly to be identified. When the coffins arrived, more than 1,500 mourners gathered to pay their respects. The graves were memorialized with a stone elephant, its trunk drooping in sadness.

“In a way, [tragedies like this] could be said to fit with the popular view of the circus as a dangerous and slapdash workplace, populated by shady transients and naturally prone to disaster,” writes Stewart O’Nan in The Circus Fire: A True Story of an American Tragedy. “But [most] risks are painstakingly calculated by expert professionals, as are the rigid logistics behind the daily world of the circus.”

The problem was when the risk couldn’t be calculated, when it arrived unanticipated in the dead of the night.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)