How White House Chiefs of Staff Help Govern

According to Chris Whipple’s new book, an empowered chief of staff can make a successful presidency

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/34/6534f8fc-0ee6-4544-87ba-bcde74b4e62e/ap_17028617162427.jpg)

When H.R. Haldeman agreed to be what incoming president Richard Nixon called his head “son of a bitch,” he knew what he was getting into. The job would require absolute authority over the rest of the White House staff. He would need an organized structure for transferring information. And above all else, Haldeman wanted to avoid end-running: private meetings between an agenda-driven individual and the president.

“That is the principal occupation of 98 percent of the people in the bureaucracy,” he ordered. “Do not permit anyone to end-run you or any of the rest of us. Don't become a source of end-running yourself, or we'll miss you at the White House.”

Those orders were more than an annoyed attempt to keep the president’s schedule clear. Haldeman may not have known it, but as head S.O.B. he would make history, essentially creating the modern chief of staff. Part gatekeeper, part taskmaster, a chief of staff is the White House’s most put-upon power broker—an employer who must juggle the demands of all branches of government and report to the chief executive.

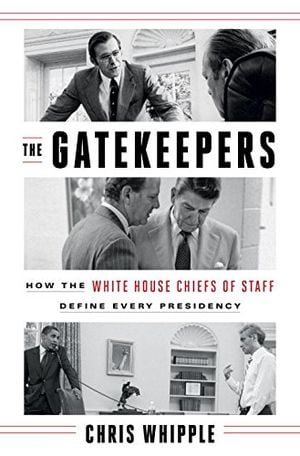

“When government works, it is usually because the chief [of staff] understands the fabric of power, threading the needle where policy and politics converge,” writes Chris Whipple in the opening pages of his new book, The Gatekeepers: How the White House Chiefs of Staff Define Every Presidency. From Richard Nixon to Barack Obama, Whipple explores the relationship between president and chief of staff and how those relationships have shaped the country over the past 50 years.

The role is an enormously taxing one, with an average tenure of just over 18 months. But when filled by competent people, it can make all the difference.

“Looking at the presidency through the prism of these 17 living White House chiefs who make the difference between success and disaster changed my understanding of the presidency,” Whipple says. “It was eye opening.”

To learn more about how the position came into existence, how it has changed over time, and what it means for the country today, Smithsonian.com spoke with Whipple about his research.

Why did you decide to cover this topic?

This whole journey began with a phone call out of the blue with a filmmaker named Jules Naudet. [He and his brother] wanted to know if I would partner with them on a White House chiefs documentary for Discovery. Even though it was four hours, I thought it barely scratched the surface of this incredible untold story about the men who really made the difference between success and disaster. After the documentary aired, I started to dig much deeper, went back for follow up interviews, talked to the chiefs’ colleagues, their staffers, two presidents and CIA directors, national security advisors. The result was the book.

When did this model of empowered chiefs of staff begin?

Presidents going all the way back to Washington had confidants. But the modern White House chief of staff began with Eisenhower and Sherman Adams, who was so famously gruff and tough they called him the Abominable No-man.

Haldeman created the template for the modern empowered White House chief of staff. Nixon and Haldeman were obsessed with this. Nixon wanted a powerful chief of staff who would create time and space for him to think. It’s a model that presidents have strayed from at their peril ever since.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of the position. He’s not only the president’s closest confidant, but the president’s gatekeeper. He’s the honest broker who makes sure every decision is teed up with information and only the tough decisions get into the oval office. He’s what Donald Rumsfeld called “the heat shield,” the person who takes fire so the president doesn’t have to. He is who tells the president what people can’t afford to tell the president themselves. And at the end of the day, he’s the person who executes the president’s policies.

What has happened when presidents have abandoned that model?

Every president who tried a different model has paid the price. Jimmy Carter really tried to run the White House by himself and he found himself overwhelmed. Two-and-a-half years into his presidency, he realized he had to appoint a chief of staff. Bill Clinton tried to run the White House much as he ran his campaign, without empowering the chief of staff to take charge. Mack McLarty was his friend, but he wasn’t given enough authority. Leon Panetta replaced McLarty and turned it around. Every president learns, often the hard way, that you cannot govern effectively unless the White House chief of staff is first among equals. That’s a lesson our current president has yet to learn.

Why did we need a new model for the modern political system?

When it comes to the White House, the team of rivals [model] is so 19th-century; it doesn’t work in the modern era. Gerald Ford tried to govern according to a model called “spokes of the wheel,” with five or six advisors of equal authority coming to him. It was a disaster. As someone put it, he was learning by fire hose.

You can’t imagine the demands of the office and how impossible it is to try and govern without an effective gatekeeper, who makes sure you get only the toughest decisions and are not drowning in minutiae. That’s the difference between governing in the modern era and governing in the 19th century.

How important is the decision about who to appoint as chief of staff?

That choice of chief makes all the difference. Reagan was famously called an amiable dunce, and that was unfair, but Reagan understood something [his predecessor] Carter did not. An outsider president needs a consummate insider to get things done. Reagan intuited this with help from Nancy Reagan and other advisers. He knew he needed somebody who could really get his agenda done, who knew Capitol Hill and how the White House worked. And James Baker was a 50-year-old smooth-as-silk Texas lawyer who wasn’t afraid to walk into the Oval Office and tell Reagan what he didn’t want to hear.

What role does personality play in the success of the chief of staff?

I think [a steady] temperament is an underrated attribute that means a lot. James Baker had it. Leon Panetta had it. He was Clinton’s second chief of staff and really turned the White House around. He was a guy who’d been around the block. He was comfortable in his own skin, could walk into the Oval Office and tell Bill Clinton hard truths. It takes somebody who is grounded and comfortable in their skin.

No president can govern by himself. It’s important to have a chief of staff who compliments his weaknesses, who is strong where the president may be weak. I think having a friend in that job is risky because friends have a hard time telling the president what they don’t want to hear. As Nancy Reagan famously said, the most important word in the title is 'staff' not 'chief.'

How has technology changed the role of the chief of staff?

Technology has obviously exploded, and there’s no such thing as a news cycle anymore. The news cycle is 24/7, and there are more platforms than ever. I do think it makes it more challenging for the president to govern and the chief of staff to execute policy, but it makes it all the more important that you have a chief of staff who understands the nexus between policy and communications. You have to be able to manage the administration’s message and make sure everyone is on the same page.

At the beginning of the book you recount the time when numerous chiefs of staff gathered together to help President Obama's first chief, Rahm Emanuel, get started. How do chiefs of staff build on each other’s legacies?

One of the extraordinary things I discovered is that no matter how fiercely partisan they may be, at the end of the day they care about the country, how the White House functions, and about the position of chief of staff, which is so little understood. I think that’s why they came together that day, December 5, 2008, that really bleak morning when it looked as though the country was on the verge of a great depression, the auto industry was about to go belly-up, and there were two wars in a stalemate. As Vice PresCheney put it, they were there to show Rahm the keys to the men’s room.

As the quote from Cheney suggests, there have been no women chiefs of staff. Can you talk about that?

I think there will be, there definitely will be. Maybe not under this administration, but there almost was under Obama. There was one woman in contention. How many female presidents have we had? How many female campaign managers have we had? Up to this point it’s been a boys’ club. I think that’s going to change.

Does Reince Priebus face any unique challenges as the current chief of staff?

Absolutely. At the end of the day, the problem, the challenge is fundamentally Donald Trump’s. If he heeds the obvious lessons of recent presidential history he will realize that he has to empower a White House chief of staff as first among equals if he wants to be able to govern.

Back in December, ten [former chiefs of staff] went to see Reince Priebus at the invitation of Denis McDonough [Obama’s last chief of staff] to give him advice, much the way they did for Rahm back in 2008. They all had the same message. This is not going to work unless you are first among equals. But [the success of the chief of staff] really all depends on the president at the end of the day. There’s almost nothing a chief of staff can do unless he’s empowered to do it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)