Head Case

Two fossils found in Kenya raise evolutionary questions

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fossil_dig.jpg)

For anthropologist Fredrick Manthi, there could be no better birthday present than finding a piece of a Homo erectus skull.

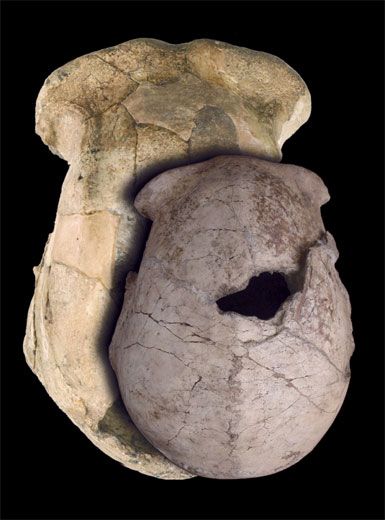

That is precisely what he got on August 5, 2000, while searching for fossils near Lake Turkana in northern Kenya. A bit of bone poking through dirt at his feet turned out to be a 1.55 million-year-old calveria, or brain case. This fossil and another unearthed during the same dig are raising new questions about human evolution.

The calveria's comparatively diminutive size suggests that H. erectus wasn't as similar to Homo sapiens as has been believed, Manthi and several colleagues contend in the Aug. 9 issue of Nature. The second fossil, a 1.44 million-year-old jawbone from an early hominin called Homo habilis, indicates that H. erectus coexisted with H. habilis, rather than being its descendant. Habilis fossils found in the past were much older than the new one.

"This opens up more questions than it answers," says anthropologist Susan Antón of New York University, one of the study's coauthors. "It raises the value of the contextual framework: where they [H. erectus and H. habilis] were living, the climate, temperature, water sources, how they kept themselves differentiated."

Antón has worked with both fossils; the jawbone is about the size of a human hand, she says, while the brain case—now the color of the sandstone that encased it for millennia—is roughly similar to that of a modern human's.

Telling H. erectus and H. habilis apart starts with the teeth. H. habilis had larger molars, an indication that the species ate more vegetation. Antón speculates that the two species divided up their habitat based on food preferences, much as gorillas and chimpanzees do today.

The small size of the H. erectus brain case could also indicate greater sexual dimorphism—a condition, found more often in primitive species, in which male and female body sizes differ dramatically.

Antón attributes this size-gap to reproductive reasons: females seek bigger, healthier mates, and bigger males have a competitive edge over smaller rivals. Since the difference in size fades as a species evolves, the calveria found in Kenya could put a lot more evolutionary distance between us similarly sized H. sapiens and our H. erectus ancestors.

That argument assumes the new fossil is indeed an H. erectus—something anthropologist Eric Delton, chairman of City University of New York's anthropology department and research associate for the Museum of Natural History, is not willing to do. Previous research suggests that the brain case's shape isn't like others found in China, Indonesia and the Republic of Georgia, says Delton, who is not affiliated with the new study.

What's more, Delton says, the brain case and jawbone could be from an entirely new species.

"Sexual dimorphism has been talked about for years," he says. "I fear that what they're basing this on is not an erectus, and the base of the house of cards will collapse. Let's go slowly and not assume erectus or habilis and think about what else it might be."

Whatever the results may be, Manthi, from the National Museums of Kenya, still rates his 33rd birthday as one of the best he's had.

"I've worked in the lake basin for 20 years," the Kenyan native, now 40, says. "This was my first human fossil."

Robin T. Reid is a freelance writer and editor in Baltimore, Maryland.