The Heiress Who Stole a Vermeer, Witchcraft in Post-WWII Germany and Other New Books to Read

These five November releases may have been lost in the news cycle

:focal(807x563:808x564)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0d/78/0d789ff4-d5f1-4723-91e2-f93b6ad7793e/booksweek13.png)

When a woman complaining of car trouble knocked on the door of a famed Irish manor, the country estate’s staff had little reason to be suspicious. But as soon as someone opened the door of Russborough House on that night in 1974, three armed men muscled their way in, seized a servant’s son and forced him to lead them and their female conspirator through the private manor’s art-adorned rooms.

Later identified by Russborough’s owner as “the leader of this whole operation,” the woman directed her associates to remove the most valuable artworks on view—including Johannes Vermeer’s The Lady Writing a Letter With Her Maid—from their frames. The group departed, 19 priceless paintings in tow, not even ten minutes later.

Initial theories suggested that the theft wasn’t politically motivated (instead, the manor’s owner told RTÉ News that the robbers’ ringleader was likely a member of an “international art gang”), but speculation turned out to be wrong on both counts. Eleven days after the heist, authorities found all of the stolen works in the trunk of a car parked at a rental cottage halfway across the island. The home’s occupant was a familiar figure in elite British society: heiress-turned-activist Rose Dugdale, who had recently made headlines for stealing paintings and silverware worth an estimated £82,000 (around £870,000, or $1.1 million, today) from her family home.

The latest installment in our series highlighting new book releases, which launched in late March to support authors whose works have been overshadowed amid the Covid-19 pandemic, explores Dugdale’s transition from Oxford student to radical militant, the little-known story of enslaved individuals escaping to Mexico prior to the Civil War, witch doctors in post-World War II Germany, environmental justice in rural America, and the surprisingly progressive nature of medieval science.

Representing the fields of history, science, arts and culture, innovation, and travel, selections represent texts that piqued our curiosity with their new approaches to oft-discussed topics, elevation of overlooked stories and artful prose. (The first volume of Barack Obama’s presidential memoir, A Promised Land, also drops this month.) We’ve linked to Amazon for your convenience, but be sure to check with your local bookstore to see if it supports social distancing–appropriate delivery or pickup measures, too.

The Woman Who Stole Vermeer: The True Story of Rose Dugdale and the Russborough House Art Heist by Anthony M. Amore

In March 1958, Elizabeth II marked the start of the social season by welcoming 1,400 debutantes to Buckingham Palace. Over the course of three days, each of these young women stood in front of the queen and curtsied before rising as newly minted members of England’s elite, ready for courtship and marriage to the country’s most eligible bachelors. But at least one participant had other plans.

As Anthony M. Amore, an author and expert in art security, recounts in The Woman Who Stole Vermeer, Rose Dugdale, daughter of a wealthy insurance scion and a recent graduate of the exclusive Miss Ironside’s School for Girls, viewed the debutante tradition as “pornographic—something which cost about what 60 old-age pensioners receive in six months.” She agreed to participate on one condition: That fall, her parents would allow her to enroll at Oxford.

Over the next ten years, Dugdale earned degrees in philosophy, politics and economics; witnessed Cuba’s revolution firsthand; documented British rule in Northern Ireland; and attended an array of student protests. By the late 1960s, this former debutante had become an outspoken activist dedicated to the twin causes of “a free Ireland and the end of capitalism,” according to Amore.

Though the IRA never officially recognized her as a member, Dugdale soon embarked on a number of missions for the paramilitary organization. Her first brush with the law took place in 1973, when she received a suspended sentence for robbing her own family home. The following year, Dugdale and several compatriots attempted to bomb a British police station in Northern Ireland, but the explosives failed to detonate.

Observers have long thought that Dugdale’s next militant undertaking was the April 1974 Russborough House heist. But Amore speculates that the burgeoning art burglar honed her skills with a February break-in at Kenwood House in north London. Authorities recovered the stolen work, Vermeer’s The Guitar Player, three months after the theft but never formally charged anyone with stealing the painting.

Unlike the still-mysterious Kenwood House heist, the Russborough House operation is incredibly well documented. Dugdale, who declared herself “proudly and incorruptibly guilty” of masterminding the theft, spent six years in prison for her part in the crime.

South to Freedom: Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to the Civil War by Alice L. Baumgartner

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, between 3,000 and 5,000 people escaped enslavement in the United States by fleeing south to Mexico, which had abolished slavery in 1837. Here, writes University of Southern California historian Alice M. Baumgartner, African American individuals earned their freedom but found their options limited to either enlisting in the Mexican military or securing employment as day laborers and indentured servants—occupations that “sometimes amounted to slavery in all but name.”

Despite the relatively grim prospects awaiting escapees, thousands of enslaved people deemed the journey worth the risk. Unlike runaways who traveled north via the Underground Railroad, the majority of those who traveled south had “only the occasional ally; no network, only a set of discrete, unconnected nodes,” according to Baumgartner. To successfully make it to Mexico, she adds, these men and women had to rely on “their own ingenuity,” often by forging documents, disguising themselves and stealing valuables needed to secure safe passage.

Mexico’s abolition of slavery played a key, albeit oft-overlooked, role in pushing the U.S. toward civil war. Most of the runaways who fled to Mexico came from Louisiana and Texas. Hoping to discourage escapes, slaveholding Southerners pushed the government to annex Texas, which had previously existed as an independent entity, in 1845; the annexation, in turn, “gave rise to the free-soil movement and led to the founding of the Republican Party and its antislavery agenda,” notes Publishers Weekly in its review.

Baumgartner’s debut book deftly traces parallels between Mexico and the U.S., examining why both permitted and later abolished slavery while offering insights on how the past continues to shape the two countries’ relationship. As the author writes in South to Freedom’s introduction, “By showing that we cannot understand the coming of the Civil War without taking into account Mexico and the slaves who reached its soil, this book ultimately contends that ‘American’ histories of slavery and sectional controversy are, in fact, Mexican histories, too.”

A Demon-Haunted Land: Witches, Wonder Doctors, and the Ghosts of the Past in Post-WWII Germany by Monica Black

Europe’s last execution on charges of witchcraft took place in 1782, when 48-year-old Anna Göldi was beheaded with a sword in Garus, Switzerland. But superstition and accusations of sorcery persisted long beyond Göldi’s death: As University of Tennessee historian Monica Black writes in an unsettling exploration of post-World War II Germany, approximately 77 witchcraft trials took place in West Germany between 1947 and 1956. And though this number is surprisingly high, it “does not [even] account for the scores more accusations of witchcraft that never ended up in court,” notes Samuel Clowes Huneke for the Boston Review.

According to the book’s description, A Demon-Haunted Land draws on previously unpublished archival materials to reveal the “toxic mistrust, profound bitterness, and spiritual malaise” that underscored West Germany’s transformation into an economic powerhouse. Following the war’s end, Black argues, a nation struggling to come to terms with the nature of evil and its complicity in the Holocaust turned to superstition and conspiracy theories as a way of coping with feelings of guilt, shame and trauma.

In this troubled atmosphere, neighborhood rivalries resurfaced as accusations of witchcraft; newspaper headlines blared out warnings of the portending end of the world; and thousands fell under the spell of faith healer Bruno Gröning, who claimed that “evil people … stopped good people from being well.” (Gröning was later found guilty of negligent homicide after one of his patients stopped her tuberculosis treatments on his advice, per Publishers Weekly.)

At the root of this unrest was a desire for absolution, a promise of redemption for wrongdoing wrought on millions of innocent people.

As the Boston Review observes, “Magical thinking offers a way of refracting responsibility for such evils—either by seeking spiritual salvation or by sublimating guilt into a mysterious and demonic other.”

Waste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret by Catherine Coleman Flowers

In Waste, environmental justice activist and Center for Rural Enterprises and Environmental Justice (CREEJ) founder Catherine Coleman Flowers reveals the U.S.’ “dirty secret”: From Alabama to Appalachia, Alaska and the Midwest, a significant number of Americans lack basic sanitation—and, in some cases, even find themselves subjected to criminal charges for failing to maintain septic tanks.

Few communities exemplify this disparity as well as Flowers’ childhood home of Lowndes County, Alabama. Here, writes the author, “an estimated 90 percent of households have failing or inadequate wastewater systems.”

The majority of those affected are low-income African American residents; as the newly minted MacArthur fellow notes on CREEJ’s website, the Alabama Public Health Department’s threats of incarceration for failing septic tanks gave rise to a culture of silence, forcing locals to cope with inadequate sanitation and any resulting health issues—a 2017 study of the county found that more than 30 percent of residents suffered from hookworm, a parasitic disease eradicated in most parts of the country but spread by sewage—on their own.

Waste blends memoir and reporting, weaving stories of Flowers’ life’s work with a broader examination of the plight of the more than one million Americans who lack access to a toilet, bathtub, shower or running water. Per Earth Justice’s Alison Cagle, most of these individuals live in rural, predominantly African American, Indigenous or Latino communities that “have insufficient infrastructure and limited access to jobs”—a trend reflective of the U.S.’ long history of systemic inequality.

Environmental justice is inseparable from human rights and climate justice, Flowers tells Emily Stewart of the Duke Human Rights Center. “When we have people in government that only value money instead of clean air and clean water, the next impacted community could be the community that didn’t expect to become a victim,” she explains. “[T]hey sat there thinking it would happen somewhere else and not in their backyard. And that’s why we should all be concerned.”

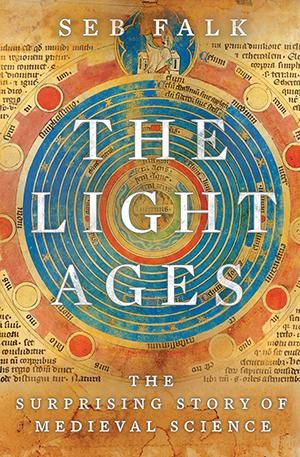

The Light Ages: The Surprising Story of Medieval Science by Seb Falk

Popular lore tends to paint the Middle Ages as “a time of superstition, brutality, short lives, non-stop dysentery and a retreat from rationality,” writes Tom Hodgkinson in the Spectator’s review of Cambridge historian Seb Falk’s debut book. But as Falk argues in The Light Ages, the so-called Dark Ages were actually relatively progressive, sparking stirring intellectual debate among monastic scholars and yielding inventions ranging from the compass to Arabic numerals, eyeglasses and mechanical clocks.

Though medieval thinkers often missed the mark—one monk mentioned by Falk donned a pair of mechanical wings inspired by the mythological Daedalus and jumped off of Malmesbury Abbey’s tallest tower, only to break both legs and find himself permanently disabled—Kirkus notes that they still managed to make “major advances in technology, mathematics, and education as well as some correct but many more fanciful explanations of natural phenomenon.”

At the center of Falk’s narrative is John Westwyk, a 14th-century English monk who devised a tool that could calculate the planets’ positions and produced a number of astronomy manuscripts. As readers follow Westwyk’s travels across Europe, they encounter a fascinating cast of characters, including a “clock-building English abbot with leprosy, [a] French craftsman-turned-spy, and [a] Persian polymath who founded the world’s most advanced observatory,” per the book’s description. Through these figures, Falk offers a sense of the international nature of medieval scholarship, debunking the image of isolated, repressive monastic communities and highlighting the influence of both Muslim and Jewish innovators.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)