From Helping Shut-Ins to Sisterly Advice, Mail-Order Magazines Did More Than Just Sell Things

The cheap monthly publications that flooded rural homes offered more than just advertising—they also provided companionship

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3d/ee/3dee29d0-c643-4fa5-9725-b680447f9f95/comfort-feb-1904-wr.jpg)

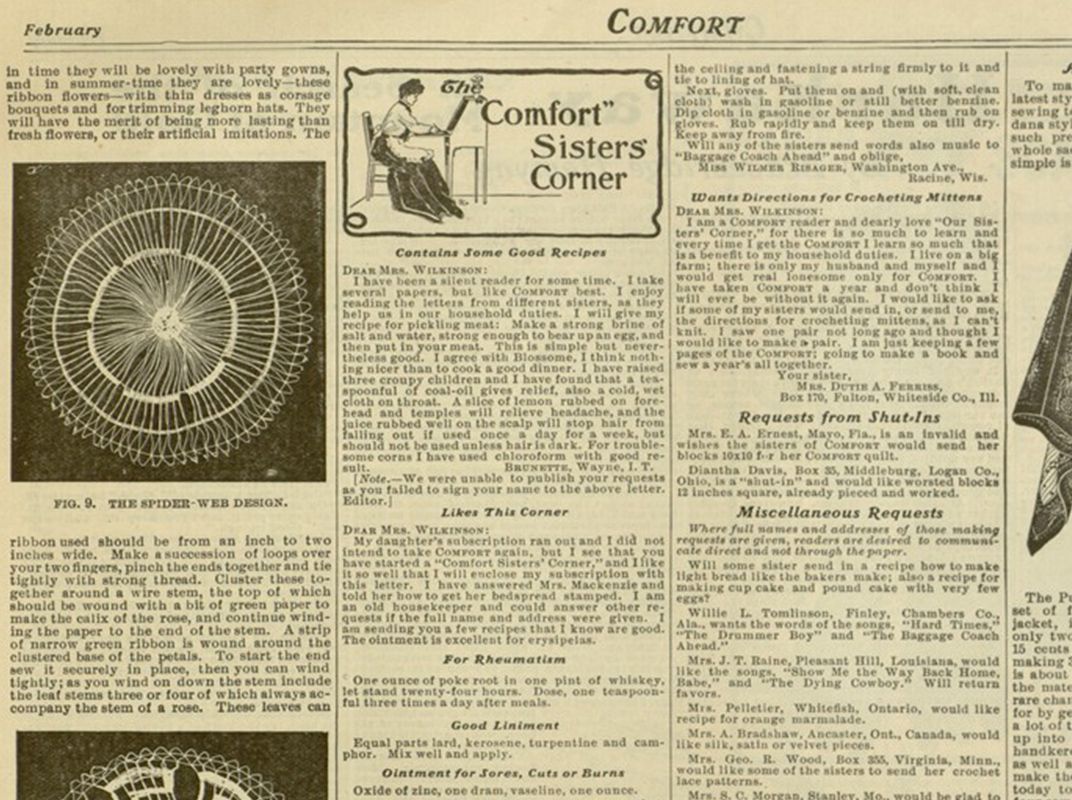

“Little Miss Fannie Allison Troutsmans writes that she is lonesome and would like to hear from Comfort readers,” the column begins. “She says she is the youngest of ten children of whom four only are living, and adds that her oldest brother, a conductor on the Southern Railroad, was killed by a train at Spartanburg, S.C.”

The appeal to fellow readers appeared at the opening of the July 1907 “Comfort Sisters’ Corner,” a staple of Comfort Magazine. The columnist includes Miss Fannie’s own words, and an address in North Carolina where “sisters” could address letters. In the same pages, one woman asked for souvenir post cards and letters, while another requested “seeds of the most popular variety… or any old-fashioned flowers, such as our grandmothers loved.”

The column ran for multiple pages, short paragraphs in tiny font sandwiched among the numerous advertisements. Comfort, after all, wasn’t just a woman’s journal; it was a mail-order magazine whose main purpose was to bring consumer culture to rural America by advertising home appliances, clothing, medicines and other goods. The original publisher, William Gannett, actually created Comfort as a way to market his nerve tonic to women. Yet as is apparent in columns like “Comfort Sisters’ Corner,” those quasi-catalogues came with a surprising side effect: communication between women that otherwise would have been impossible.

In the decades following the Civil War, rapidly advancing printing press technology and an expanding postal delivery network allowed the number of publications in the U.S. to explode. Whereas only 700 publications existed in 1865 (including Harper’s Weekly, Confederate Veteran and Southern Historical Society Papers), they numbered more than 3,000 by 1885, and more than 4,400 by 1890. Those numbers, and the circulation of publications, continued to increase as the United States Postal Service began experimenting with Rural Free Delivery in the 1890s, bringing mail directly to the 65 percent of the population who lived in rural areas rather than leaving the mail at drop-off points. (It wasn’t until 1920 that the census found more people living in urban areas—towns with more than 2,500 inhabitants—than in rural areas.)

Among the first mail-order magazines to appear in the post-Civil War years was E.C. Allen’s People’s Literary Companion, printed in Augusta, Maine and distributed around the country starting in 1869. Thanks to Allen’s pioneering work in Maine, Augusta became a hub for publishing, with 17 titles printed in the town, reaching a maximum circulation of over 3 million. Not only were the magazines written mainly for women, they were often made by women as well: of the 1,309 people working in the publishing industry statewide in 1900, women accounted for 615, just under 50 percent. It was even reported that Allen himself, the “Mail Order King,” required the opinion of female clerks whenever he chose a picture for distribution in his magazines, writes Robert Lovett in the Bulletin of the Business Historical Society.

But the magazines flowing out of Augusta, with names like Thrifty Farmer, American Woman, Golden Moments and Comfort, were often cheap, shoddily printed rags meant to turn rural women and families into consumers. Publishers would send them for free to one-time subscribers, print ads for their publications in other magazines, and offer incentives for signing up new subscribers, which allowed the number of readers to grow rapidly—whether or not the magazines were actually being read. Compared to mass circulation women’s journals like Ladies’ Home Journal and Delineator, publishers of these mail-order magazines cared less about readers renewing their subscriptions than about having huge circulation lists with which to entice advertisers. Even though Good Housekeeping and journals like it undoubtedly crammed advertisements on as many pages as possible, those publications also hewed more closely to an editorial mission of providing readers with housekeeping advice, substantive fiction and poetry, and columns on fashion.

As advertising analysts Ernest Elmo Calkins and Ralph Holden wrote of Ladies’ Home Journal and Comfort, the two different magazines represented “extreme types [of publications] and their respective constituencies; the one, the highest type of an advertising medium… reaching well-educated, well-to-do, intelligent American women; the other, poorly printed… and reaching an uneducated and credulous class [whose] readers buy only the most inexpensive things, but large numbers of them do buy, so that the space is worth what it costs the advertisers.”

Mary Ellen Zuckerman, a professor of marketing at the State University of New York, Geneseo and author of A History of Popular Women’s Magazines in the United States, 1792-1995, acknowledges that both types of magazines contributed to the flood of consumer goods reaching rural markets. But, she says, “In a funny way, the mail-order magazines were almost more honest about their purpose. You knew when you got it that it was going to be filled with a lot of advertising.”

Take a publication like Comfort. It was one of the first magazines to reach a circulation of over one million, charging only 15 cents for a yearlong subscription for monthly editions of the magazine. As librarian Clara Carter Weber writes, “Comfort was in business to sell everything you could think of, from sheet music, parlor organs, and peanuts, to an ‘oil portraiture’ of Admiral Dewey and a ‘Magical Sponge,’ the ‘wonder of the 20th century.’” Peruse the pages of old editions of Comfort and you’ll find advertisements offering a free pocket watch for those willing to sell bluing dye for laundry, and “Duby’s Ozark Herbs” to dye gray hairs without coloring the scalp, and cheap fur scarves and muffs, and medical cures like Dr. Coffee’s 80-page eye book to cure all eye diseases.

But surrounding those advertisements were short stories and recurring columns, like “Talks with Girls” and “Poultry Farming for Women.” Really, Zuckerman says, the mail-order magazines were also forms of communication.

“If you think about the lives of the women on these farms, a lot of the day in and day out they were isolated. Reading these publications was a communication lifeline in a way,” Zuckerman says. “If you could write in and see something you wrote in print, and see other women writing about things of interest or concern to you, it provided a very strong connection that’s hard for us today to understand, because we’re so inundated with ways of communicating.”

Just consider the telephone, invented by Alexander Graham Bell in 1876. At the turn of the century, only 10 percent of all households even had telephone services. For women living on farms far from anyone but their family members, mail-order magazines offered an escape from daily life, and also a way to make a tangible connection to other lonely women. In addition to “Comfort Sisters’ Corner,” another regular feature of the magazine was requests from “Shut-Ins”—women too sick or old to leave their houses, who depended on the charity of neighbors and other readers for survival. “I intend to remember the shut-in whenever I can,” writes Edna Peterson of Biggsville, Illinois in the July 1907 edition.

But even with the communication they offered rural women, mail-order magazines weren’t destined for longevity. Many ceased publication after 1907, when the Post Office required lists of paid subscribers for magazines asking for a lower mailing rate. Among the mail-order magazines that survived the culling were Woman’s World and Comfort, both of which lasted until 1940.

“I think they outlived their purpose,” Zuckerman suggests. “As roads improved and people had better transportation, they were able to access larger towns and cities to do their shopping, so they didn’t have to rely on mail order. It’s ironic because now we’ve circled back with Amazon. Everybody wants to do shopping from home and not go out.”

As transportation technology changed, so too did communications. By 1948, the United States had 30 million connected telephones, and reaching out to friends from afar was growing easier, even in rural areas. Catalogs like Sears and Montgomery Ward became the new way to make domestic purchases. But for a brief period, mail-order magazines had played a vital role for rural women: making them feel less alone on their farms and homesteads, and empowering them to share their experiences with others.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)