The New Archaeology of Iraq and Afghanistan

The once-fortified outposts that protected U.S. troops are relics of our ambitions abroad

:focal(1571x2563:1572x2564)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/56/5d/565d1c4c-f348-4280-82d0-fda6843a0296/cropped_opening_image.jpg)

Late in 2001, as Osama bin Laden and his harried entourage slipped into Pakistan over a mountain pass near Tora Bora, Afghanistan, a contingent of U.S. Marines seized the long-abandoned American embassy in Kabul, restoring the compound to American control. The Taliban, it seemed, had been routed. Al Qaeda was on the run. A new era was unfolding in real time, organized by an American military that cast itself as remade after the sorrows of Vietnam.

The reclaimed embassy, small and quaint, was an accidental time capsule. Like an unexpected archaeological find, it remained stocked with artifacts from a previous time—aged booze and magazines and paper calendars from 1989, the year its diplomatic staff had abruptly withdrawn from Afghanistan as the country sank into civil war.

With the return of the Americans, the place was being reordered by the hour. A guard post appeared at the front gate. Here Marines stood beside a curiously modern and geometrically simple bunker, a defensive position made of prefabricated boxes of heavy wire with synthetic mesh liners, each filled with gravel, sand or dirt. The boxes, arranged as a fighting position and blast wall, were neat and stackable, a labor-saving update on the sandbag.

People asked: What are these? Hesco, the Marines answered. The name is shorthand for HESCO Bastion, the company that manufactured them.

Roll the clock forward 17 years, and those drab little crates are the signature marker of a generation’s worth of American war. The United States has now been fighting—in Afghanistan, Iraq or elsewhere—more than 1,500 days longer than its Kabul embassy was closed, long enough to scratch signs of nearly forgotten campaigns into the earth. During all these years of war, the troops spread out over the map, creating outposts across occupied lands. Almost everywhere they went they brought Hesco barriers. The wars gave license to unsettling new norms—the prominence of the improvised explosive device, the routine circulation of battlefield snuff films, the adoption of killing by remotely piloted aircraft, to name but a few. Prefab Hesco frames for expeditionary earthworks became this violent universe’s prevailing physical feature. And then, in the time it took for the Pentagon’s campaigns to crest, stall and contract, the same frames, abandoned across arid landscapes, became the wars’ characteristic ruin.

I worked from many now-disowned bases while reporting for the New York Times and researching my recent book The Fighters: Americans in Combat in Afghanistan and Iraq, a chronicle of the American combatants’ experience of both wars. These outposts were the interconnected dots on the Pentagon’s short-lived maps, the centers from which senior officers hoped their forces might create security and then stability in areas where criminals and militants thrived. The wars did not go as planned, and today, in the age of the internet and open-source satellite imagery, the old positions are dots of a different type—on the computer screens of veterans, for whom Hesco ruins are portals to memory and reflection.

How did Hesco assume such an outsized role? Troops used the crates, available in multiple sizes, for much more than easily hardened perimeters. They were so universally useful, for force protection and engineer-free construction alike, that they became ubiquitous. Hesco formed blast walls around command posts and the small wooden B-huts that served as housing at mid-size and larger bases. They ringed fuel depots and ammunition bunkers. They were erected to save lives during long-range fights, defending mortar pits and artillery batteries and the blast shelters that troops dashed into during incoming rocket or mortar fire.

With time Hesco came to signify neighborhood, and compounds made of the barriers developed standard sights—guard towers, rows of portable toilets and crude latrines, acres of gravel and crushed stone that served as helicopter landing zones. Lengths of PVC pipe that angled through Hesco walls or down into the ground functioned as open-air urinals—“piss tubes,” troops called them. Small gyms, sometimes replete with shipped-in dumbbells and Olympic weights, were also organic to it all, as were idiosyncratic odors—cigarette smoke, diesel fumes, the drifting stink of human waste. An acrid odor of melted plastic and God knew what else that rose from ever-smoldering trash—“burn pits”—became the basis for medical claims for inhalation-related injuries that many veterans consider their generation’s Agent Orange.

With Hesco villages came common hassles. During dry seasons, a fine sand—“moon dust”—settled over or penetrated everything: laptops, cameras, socks, the spaces between teeth. In wet weather, the dust formed a gummy mud. Sometimes it was like cake batter; other times, like brown grease. And Hesco did not guarantee safety. Some troops and officers, while recognizing the value of easy-to-erect barricades, also saw them as symbols of American fear and an overwrought inclination toward force protection. Tall walls created practical dangers. Hesco perimeters, when stacked high, restricted vision, allowing militants to lob grenades into outposts or to hide bombs near gates.

If all of this sounds dreary, it was. But in other ways Hesco compounds were not dreary at all. Troops lived rich patches of their lives in these small spaces. To the extent that sanctuaries for foreigners on occupation duties existed, Hesco islands were them, places of relative safety in seas of confusion and violence. Inhabitants made the most of them. Military routines consumed much of the time—cycles of maintenance, cleaning, guard shifts, mission planning and precious rest. But troops also cooked, organized pranks, worked out, watched porn and communed with their Iraqi and Afghan military and police counterparts to drink tea and smoke cigarettes. (At some outposts, especially in Afghanistan, a few of them smoked local marijuana and hashish.)

Dogs infiltrated the barriers seeking companionship and discarded food. Troops adopted these visitors even when their presence was officially banned, owing to risks of parasites and rabies. (Orders to shoot dogs were repeatedly ignored.) In the eastern Afghan mountains a few outposts were watched over by monkeys. One remote position was regularly visited by a cow. One day I watched her walk onto the grounds to feast on soggy muffins in the burn pit.

Most of these outposts exist today only as memories and discarded Hesco, the lingering traces of a brief occupation. Outpost Omar, north of the center of Karma, Iraq, sat beside a two-lane asphalt road and surrounded by a maze of canals and farm fields. It looked over an area where an offshoot of Al Qaeda morphed into the Islamic State, a treacherous spot plagued by snipers and roadside bombs. After several years within its walls, enduring gunfire and a truck-bomb attack, the Marines departed and Karma became the scene of fresh fighting. Omar, once deemed essential, was an afterthought.

Combat Outpost Lowell, near Kamu, Afghanistan, was named for Army Specialist Jacob M. Lowell, who was fatally shot while on patrol in 2007. Soldiers erected Lowell on the grounds of a small castle in a canyon beside the Landai River, swift and green. It had been an Afghan king’s hunting lodge. Americans surrounded the mini-fort with Hesco and reinforced some of the stone walls. The position, home to fewer than 100 soldiers, was ringed by mountains and about as defensible as the bottom of an elevator shaft. After the Taliban destroyed a bridge on the valley’s sole road, Lowell was unreachable by land. Kept alive by airstrikes, distant artillery fire and helicopter resupply, it became untenable—a sign not of American power, but of Pentagon overreach. The last few dozen soldiers left in 2009, evacuating by night. The Hesco remained behind, the footprint of a stymied empire reconsidering where it tread.

Like an archaeological site, the remnants of Camp Hanson carry the same jarring message, but at a far more costly scale. The camp was named for Lance Cpl. Matthias N. Hanson, a Marine who died in a gunfight in February 2010, during the opening days of the most ambitious Marine Corps operation of the war. Almost a decade after the Marines had reclaimed the embassy in Kabul, Lance Cpl. Hanson was part of the sweep of Marjah, a Taliban and drug-baron stronghold atop an irrigation canal system the United States had sponsored during the Cold War. More than two battalions descended on the place. Marines who had been in elementary school in 2001 fought their way across hamlets and opium poppy fields to set up a network of outposts, from which they and their armed Afghan counterparts were to usher in government services and wean the farmers from their poppy-growing habits. Camp Hanson, built within days of Lance Cpl. Hanson’s death,was one of the largest of many American positions. It became a battalion command post.

For a short while, Camp Hanson was a hub. Dated imagery of it online shows a hive of military activity—tents and huts and shipping containers near rows of armored trucks, along with a small blimp to hold its security cameras aloft. In more recent pictures, Hanson is empty. The faint outlines of Hesco barriers tell of a grand campaign lost to the unsparing realities of war on the Afghan steppe, where the Taliban outlasted the Pentagon’s plans. What remains are the ruins of a headstrong military’s self-assured try, doomed to failure—the refuse of a superpower that misjudged its foes and sent a generation of youth out into badlands, only to decide, all those caskets and lost limbs later, that it had changed its mind.

It’s a story with outlines an archaeologist would recognize.

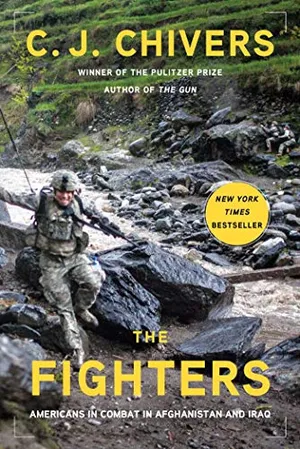

The Fighters

Pulitzer Prize winner C.J. Chivers’s unvarnished account of modern combat, told through the eyes of the fighters who have waged America’s longest wars.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.