The Hidden Power Behind D-Day

As a key advisor to F.D.R., Adm. William D. Leahy was instrumental in bringing the Allies together to agree upon the invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe

:focal(1011x242:1012x243)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bb/f5/bbf5f773-b1ee-4eeb-820d-4f2b6184b45b/yalta.jpg)

In early June 1944, as Allied troops in England made their final preparations before embarking on the greatest invasion of all time, the eyes of the American media turned not to the beaches of Normandy, but to Mt. Vernon, Iowa, a speck of a town more than 4,000 miles from Hitler’s Fortress Europe. There, at a small liberal arts college, Admiral William D. Leahy, the highest-ranking member of the American military, was set to give a commencement speech before an assemblage of reporters.

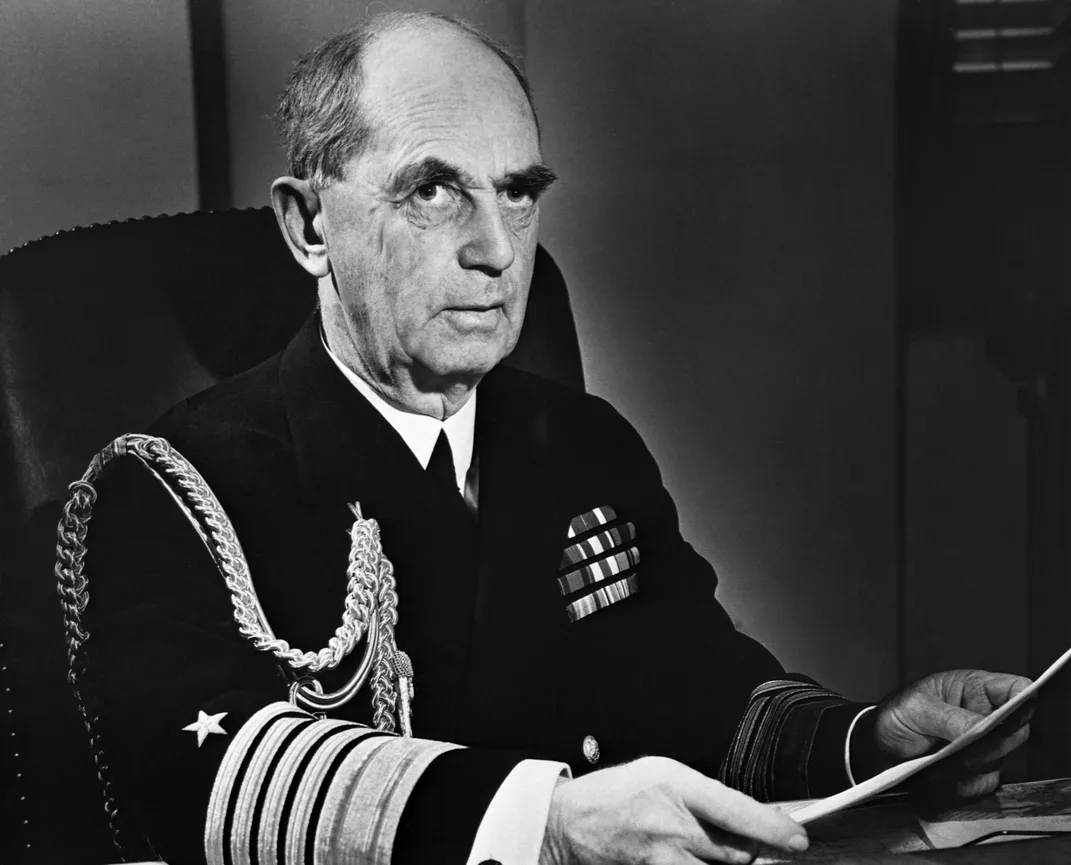

Leahy is little remembered. He can be seen in countless wartime photographs hovering a few feet from President Franklin Roosevelt with a sour grimace on his face, though today one could be forgiven for assuming that the man in the white peaked cap and the gold braids was some anonymous aide, rather than one of the most powerful men in the world.

Admiral Leahy had been Franklin Roosevelt’s friend for years, going back to Roosevelt’s early job as the assistant secretary of the Navy. Two decades later, Roosevelt was in the White House, and Leahy had risen to the top position in the Navy. Upon the admiral’s retirement in 1939, the president confided to him that if war came, Leahy would be recalled to help run it. And call him Roosevelt did, making the admiral after Pearl Harbor the first and only individual in American history to bear the title “Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief.” Thanks to the trust that had built over their long friendship, Leahy was tasked with helping FDR grapple with the enormous strategic decisions of World War II.

Standing before an audience of eager graduates and their families at Cornell College, as well as newspaper photographers, the four-star admiral—by the end of the year he would become the first officer of the war to receive his fifth star, making him forever outrank his more-famous counterparts such as Dwight Eisenhower, Douglas MacArthur and George Marshall—spoke of the heavy price of freedom.

“Everybody may have peace if they are willing to pay any price for it,” he said. “Part of this any price is slavery, dishonor of your women, destruction of your homes, denial of your God. I have seen all of these abominations in other parts of the world paid as the price of not resisting invasion, and I have no thought that the inhabitants of this state of my birth have any desire for peace at that price…”

Within 24 hours, some 2,500 Americans would be killed in France. Leahy was the only man in the auditorium who knew this cataclysm was coming. Indeed, it was the very reason he was in Iowa in the first place.

Seventy-five years later, Operation Overlord, better known as D-Day, is part of the American story, but at the time, the when and the where were hardly inevitable. In fact, the Allied high command had bickered over it for more than two years. Even within the American ranks, the premise of an invasion was hotly debated. From the onset of the wars with Japan and Germany, General George Marshall, the chief of staff of the U.S. Army, believed that Hitler, rather than Japanese Emperor Hirohito, was America’s great enemy, and that the war in Europe should receive the overwhelming weight of American attack. The best way to defeat the Germans, Marshall insisted, was to invade France as soon as possible. In late 1942, Marshall believed that an invasion should occur in 1943—he was partial towards a landing in Brittany—and that the United States should send almost all its available men and equipment to Great Britain to prepare for such an attack.

As a Navy man—and more importantly, as the first chairman of the newly-formed Joint Chiefs of Staff—Leahy had a different opinion. Leahy cared about the control of communications, dominating the seas, and wearing down the enemy with sea and air power. He wanted the United States to fight a balanced war between Europe and Asia, believing that the fate of China, also at war with Japan, was at least as important for the future of the world as anything happening in Europe. Leahy was thus strongly opposed to committing the vast majority of American forces on a very risky 1943 invasion of France. He wanted to wait until 1944, when he believed that the U.S. would have such an overwhelming advantage on the sea and in the air that any invasion could get ashore and stay ashore without too many casualties.

It was during this debate that the importance of Leahy’s relationship with Roosevelt was fully felt. Every morning in the White House, the admiral met privately with the president for a full briefing of the state of the war. Leahy was Roosevelt’s confidant and sounding board for decisions great and small, from the allocation of forces to the prioritizing of military production. Furthermore, the two men could relax together over a meal, a cocktail or a cigarette, a bond that FDR, under enormous stress and facing failing health, particularly valued. Marshall, on the other hand, was stiff and unfriendly with the president—he famously glared at Roosevelt when the president casually called him “George.” As a result, the two hardly ever met alone.

Leahy’s closeness with Roosevelt spiked any possibility of invading France before American troops were ready. Whenever Marshall pressed the idea of a 1943 invasion, Roosevelt and Leahy pushed for delays. They did not order Marshall to abandon the plan, they simply refused to authorize it. In January 1943, Marshall ran into further opposition from the British delegation led by Prime Minister Winston Churchill at the Casablanca Conference. Having failed to convince the president and his closest advisor to support his plan, Marshall was forced to accept that the attack would not occur until later.

Yet even a 1944 invasion was not a fait accompli. Churchill, haunted by memories of the horrific trench warfare of the First World War, did not want to risk large British casualties by invading France—maybe ever. Churchill preferred fighting the Germans up through Italy or in the Balkans, as he put it, in the “soft-underbelly” of Europe. Not only would this preserve British troop reserves, in his view, it would also open up the Mediterranean, restoring the quickest lifeline to India, the jewel of the crown in the British Empire and a colony that Churchill, for one, was desperate to hold onto.

With a 1943 invasion now out of the question, Leahy and Roosevelt strongly supported launching D-Day in 1944, when they believed America and Britain would be ready. A sideshow in southern Europe held no interest for them. Marshall aligned with their vision, and the American army joined with the Navy and the White House to develop one plan that had overall support. For the next four conferences—Trident, Quadrant, and Sextant/Eureka, ranging from May to December 1943—the Americans squared off against the British at the negotiating tables, backed by the raw force provided by the size of the American war economy.

At both Trident and Quadrant, Leahy and Roosevelt, working with Marshall, applied such brutal pressure that the British would reluctantly succumb to American demands, and Churchill was forced to sign up for a strategic plan based around the invasion of France in 1944. And yet almost immediately after each conference ended, Churchill would attempt to wriggle out of the commitment.

In late November 1943, the “Big Three” finally met together for the first time. Leahy accompanied Roosevelt to Tehran for a talk with Churchill and the Soviet Union’s leader, Joseph Stalin. The Soviet dictator had no time for indirect approaches through the Mediterranean. He wanted an invasion of France as soon as possible so as to engage as many units of the German Army as possible, thereby taking the pressure off his own beleaguered troops fighting at the edges of Eastern Europe. Speaking with a bluntness that impressed Leahy, Stalin disparaged any plan of Churchill’s that did not make D-Day the focus of Anglo-American operations in 1944. His directness was a God-send to Leahy and Roosevelt, who took advantage of it throughout the talks. Whenever the British acted like they might once again oppose the invasion, either the president or the admiral would say that they needed to launch D-Day because they had promised the Russians. At one point, after the British had objected once again to D-Day, arguing that any invasion needed to wait until the Germans were so weak that Allied casualties would be low, Leahy attacked, asking whether the British believed “that the conditions laid down for Overlord would ever arise unless the Germans had collapsed beforehand.”

Faced with such obstinacy, Churchill had to give in. At the end of the conferences there was no way out—it was a crushing defeat for Churchill, one that hit him so hard that he suffered a nervous breakdown shortly thereafter and went incommunicado from the British government for a few weeks in an attempt to recover.

When news of the landing broke the next morning, June 6, 1944, Leahy’s mission at hand was complete—America’s top military man was seen out on a photo op in an Iowa corn field, distracting attention away from the invasion. That evening, Leahy quietly slipped back to Washington to be reunited with his old friend and strategic confidante, President Roosevelt. Together in the White House, they could do little but watch and wait, hoping that Operation Overlord came to a successful conclusion.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.