Hiroshima, U.S.A.

In 1950, a popular magazine depicted what an atomic bomb would do to New York City—in gruesome detail

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1950-aug-6-colliers-p12.jpg)

There’s no city that Americans fictionally destroy more often than New York.

New York has been blown up, beaten down and attacked in every medium imaginable throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. From movies to novels to newspapers, there’s just something so terribly apocalyptic in the American psyche that we must see our most populous city’s demise over and over again.

Before WWII, these visions of New York’s destruction took the form of tidal waves, fires or giant ape attacks — but after the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan in Hiroshima and Nagaski, the atom was suddenly the new leveler of cities.

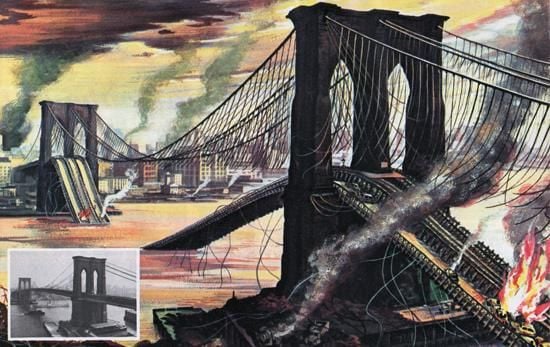

The August 5, 1950 cover of Collier’s magazine ran an illustration of a mushroom cloud over Manhattan, with the headline reading: “Hiroshima, U.S.A.: Can Anything be Done About It?” Written by John Lear, with paintings by Chesley Bonestell and Birney Lettick, Collier’s obliterates New York through horrifying words and pictures. The first page of the article explains “the story of this story”:

For five years now the world has lived with the dreadful knowledge that atomic warfare is possible. Since last September, when the President announced publicly that the Russians too had produced an atomic explosion, this nation has lived face to face with the terrifying realization that an attack with atomic weapons could be made against us.

But, until now, no responsible voice has evaluated the problem constructively, in words everybody can understand. This article performs that service. Collier’s gives it more than customary space in the conviction that, when the danger is delineated and the means to combat it effectively is made clear, democracy will have an infinitely stronger chance to survive.

The illustrator who painted the cover was Chesley Bonestell and it is no doubt one of the most frightening images to ever grace the cover of a major American magazine. Opening up to the story inside, we see a city aflame.

A kind of wire service ticker tape runs across the top of the images inside the magazine:

BULLETIN NOTE TO EDITORS — ADVISORY ONLY — NEWARK NJ — HUGE EXPLOSION REPORTED IN LOWER NEW YORK CITY. IMMEDIATE CONFIRMATION UNAVAILABLE. WIRE CONNECTIONS WITH MANHATTAN ARE DOWN. NEW YORK HAS ADVISED IT WILL FILE FROM HERE SHORTLY . . . BULLETIN — HOBOKEN NJ — DOCK WORKERS ON THE NEW JERSEY SIDE OF THE HUDSON RIVER THIS AFTERNOON REPORTED A THUNDEROUS EXPLOSION IN THE DIRECTION OF NEW YORK CITY. THEY SAID THEY SAW A TREMENDOUS BALL OF FIRE RISING INTO THE SKY

The first few pages of the article tell the story of a typical Tuesday in New York City, with people going about their business. Suddenly a radiant heat is felt and a great flash engulfs the city. People in Coney Island mistake it for a lightning bolt. A housewife in the Bronx goes to the kitchen window to investigate where the light came from, only to have the window smash in front of her, sending thousands of “slashing bits” toward her body. As Lear describes it, it doesn’t take long for “millions of people, scattered over thousands of miles” to discover what has taken place.

The aftermath is one of great panic with emergency vehicles unable to move and people rushing to find transportation. Collier’s would touch on this theme of urban panic a few years later in their August 21, 1953 issue. One of the many fictional characters we follow in this story (an Associated Press reporter named John McKee) somehow manages to hail a cab in all this madness. McKee eventually gets to his office and begins reading the bulletins:

(NR) New York — (AP) — An A-bomb fell on the lower East Side of Manhattan Island at 5:13 P.M. (edt) today — across the East River from the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

The story goes on to describe how news coverage is largely crippled by the fact that 16 telephone exchanges were out, leaving 200,000 telephones useless. Ham radios, naturally, come to the rescue in their ability to spread emergency messages.

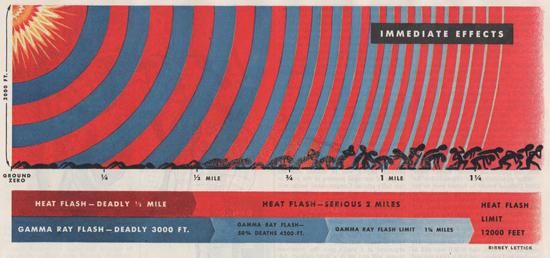

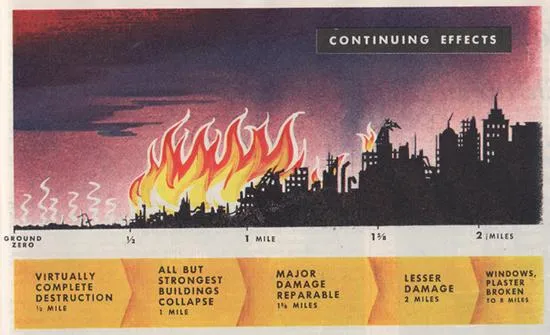

The cover ran almost 5 years to the day of the U.S. bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. The military was able to go in after the attack and measure the extent of the devastation. The graphs below, which ran with the Collier’s article, explain what kind of impact would be felt at various distances from ground zero.

The article explained that our understanding of what a nuclear attack on New York would look like came straight from U.S. measurements in Japan:

The opening account of an A-bombing of Manhattan Island may seem highly imaginative. Actually, little of it is invention. Incidents are related in circumstances identical with or extremely close to those which really happened elsewhere in World War II. Property damage is described as it occurred in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, with allowance for differences between Oriental and Occidental standards of building. Death and injury were computed by correlating Census Bureau figures on population or particular sections of New York with Atomic Energy Commission and U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey data on the two A-bombs that fell on Japan. Every place and name used is real.

This Collier’s article wasn’t the first to warn of the devastating effect an atomic bomb could have on New York. A four-part series ran in newspapers across the country in April of 1948 which also described how awful a nuclear attack on New York could be. Written by S. Burton Heath, the first article in the series ran with the headline, “One A-Bomb Dropped In New York Would Take 800,000 Lives.”

One atomic bomb, exploded over New York’s Times Square on a working day, could be expected to kill several hundred thousand men, women and children.

No reputable atomic expert, in Washington or elsewhere, will estimate the exact number. The New York fire department says 100,000. On the basis of Hiroshima and Nagasaki it would be more than 800,000. The most reliable experts say the fire department’s guess is absurdly low. They think the bigger figure is too high.

After the surreal devastation that we witnessed during the terrorist attacks upon New York on September 11, 2001 ,we have some idea of what true horror looks like when inflicted upon a major American city. But a nuclear bomb is still something altogether different. The level of destruction that would result from nuclear warfare remains an abstraction for many — until you flip through old magazines of the Cold War.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)