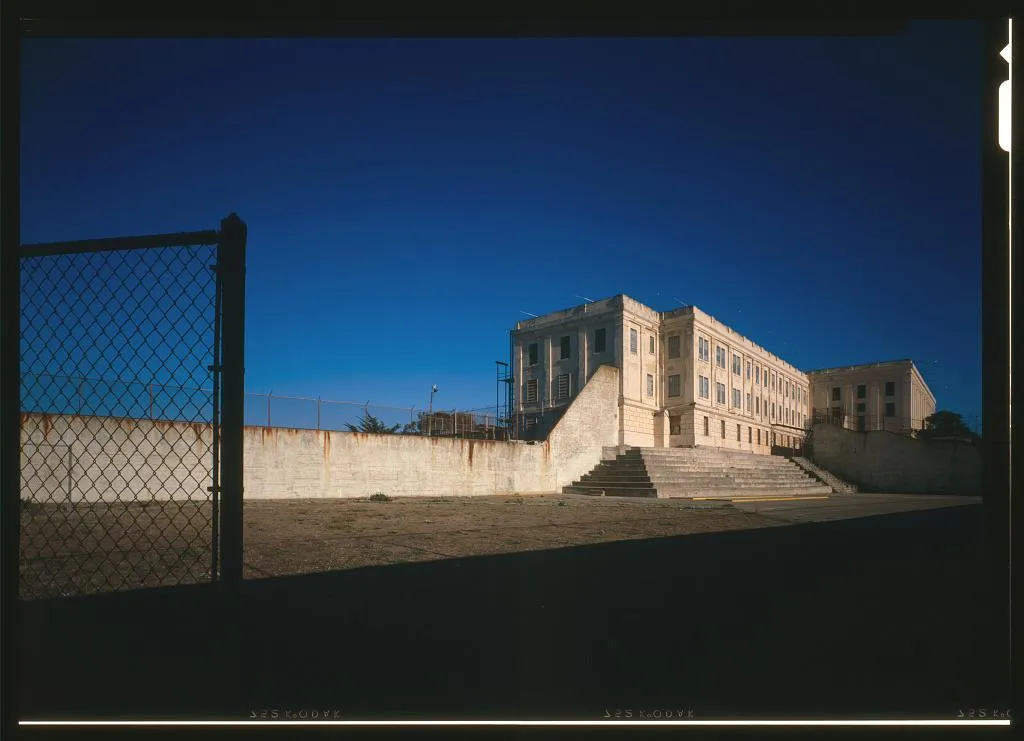

Alcatraz’s Captivating Hold on History

Fifty years after Native American activists occupied the island, take a look back at the old prison in San Francisco Bay

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0e/11/0e119c53-b9fa-498f-91b9-1d77090cc2da/nov2019_e23_prologue_copy.jpg)

Fifty years ago this November, a group of Native American students arrived by boat on Alcatraz Island because, they said, it reminded them of home. Like many Indian reservations, Alcatraz had no modern facilities or fertile soil. The federal prison had closed six years earlier, and the island had been designated “surplus government property.” The students, who called themselves the Indians of All Tribes, offered $24 in glass beads and red cloth for Alcatraz. They noted that this was more than Europeans had paid Indians for Manhattan Island 300 years earlier, but that “land values have risen over the years.”

Though the occupation seemed at first like a publicity stunt, the Indians had a vision for the island, including a Native American cultural center. But the protest collapsed after 19 months because of a series of tragedies and declining public support. Instead, the abandoned prison grew into one of the nation’s premier tourist attractions, with more than 1.4 million visitors every year.

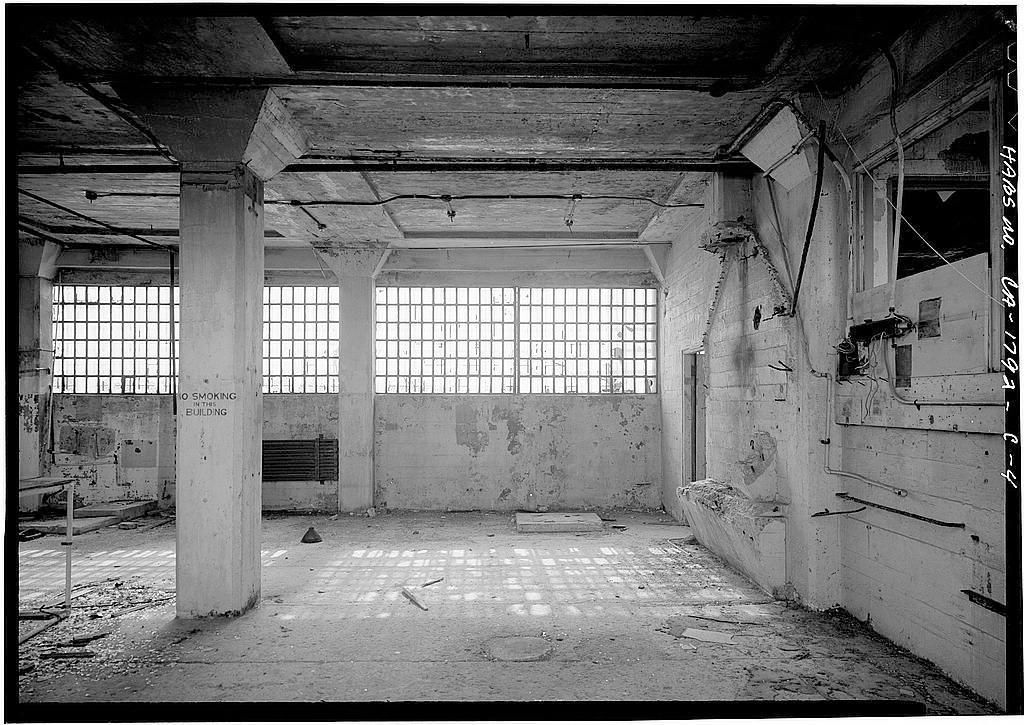

On the one hand, the popularity of Alcatraz reflects our fascination with freedom. The mundane liberties of daily life look more valuable than ever when considered while standing amid the forbidding cells, now with peeling paint and cracked concrete. On the other hand, the island’s starkly beautiful setting, within sight of San Francisco’s skyline, is itself compelling. Even inmates couldn’t help admiring it. “I will never have such a magnificent view in any other prison,” wrote Morton Sobell, a co-conspirator of the Cold War spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

Such prime real estate would seem to have had better uses, but Alcatraz is barren, windswept and without a natural source of fresh water. The Spanish explorer who named the island in 1775, Juan Manuel de Ayala, passed it by in search of a friendlier harbor. The federal government built the Pacific Coast’s first lighthouse on Alcatraz in 1854, and the Army constructed a fort there, where it imprisoned Confederate soldiers during the Civil War. It continued to serve as a military prison until 1933, when the Justice Department took control and formed the Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary the following year.

By concentrating so many criminals in plain view, the government drew attention to the men it was hoping to make disappear. Newspapers scrapped for every juicy detail. When Al Capone headed there in 1934, the San Francisco Chronicle reported, “Capone sagged at his first glimpse of the prison.” In September of that year, the paper revealed that George “Machine Gun” Kelly had begun serving time there. Former inmates grumbled about harsh treatments—like the “no talk” rule lifted only in the recreation yard on Saturday afternoons—enhancing the prison’s fearsome reputation.

By the end of the 1930s, when the Alcatraz prison population reached its peak with 302 inmates, the federal government ran 14 prisons, and all of them were hard to escape from. But the idea of escaping from the Rock was especially romanticized. The waters of the San Francisco Bay were cold, with strong currents and sharp rocks. The journey was not exactly impossible: In 1934, just before the prison opened, a 17-year-old girl swam from Alcatraz to the mainland in 47 minutes. But the stories of several inmates who tried to make the break were turned into (usually whitewashed) movies: Henri Young in Murder in the First, Robert Stroud in The Birdman of Alcatraz and Frank Morris in Escape from Alcatraz.

The Native American students who occupied the island beginning in 1969 made savvy use of the place’s notoriety. “Here, in this white man’s prison, we have found freedom for the first time,” LaNada Means, a student organizer, told the influential San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen.

The activists, who had brought sleeping bags and moved into the old cells, cooked on open fires, held nightly dances and celebrated “Un-Thanksgiving Day.” News coverage attracted supporters, including celebrities such as Marlon Brando, who in turn attracted coverage. But the Alcatraz demonstrators, who had to contend with no electricity after authorities shut it off, among other hardships, grew discouraged. The 12-year-old stepdaughter of the protest’s organizer, Richard Oakes, fell to her death from the third floor of a former guard residence. A fire burned down the historic lighthouse. Federal officials evicted the protesters on June 11, 1971.

The Indian rights leader Russell Means, who briefly participated in the Alcatraz occupation, credited the action with launching a new era of protests and legislation. “There was that spark at Alcatraz and we took off,” he recalled in 2002.

Today, even at the old prison itself, which is run by the National Park Service, fleece- and sneaker-clad tourists who venture out to see where Al Capone holed up can also see that the protesters left their mark. Rangers have preserved their graffiti. “Peace and Freedom. Welcome,” the water tower reads. “Home of the Free Indian Land."

How to Escape Alcatraz

In the century that a prison operated on Alcatraz, at least 71 inmates got off the "breakproof" island. As many as 28 may have made it to freedom

Research by Matthew Browne