One Hundred Years Ago, Northern Ireland’s ‘Unholy War’ Resulted in a Deadly Summer

In July 1921, an outburst of sectarian violence in Belfast claimed 16 lives on the eve of a truce between Great Britain and Ireland

:focal(791x532:792x533)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/34/78/347888c5-3133-4816-be31-a34be80e95ed/screen_shot_2021-07-15_at_23138_pm.png)

By the summer of 1921, Ireland’s bid for independence from Great Britain had all but reached an impasse. After nearly two-and-a-half years of fighting, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) had exhausted its supplies of weaponry and ammunition; the British Empire, meanwhile, was ready to end the protracted and increasingly unpopular guerrilla war against its neighbor.

The beleaguered combatants agreed to a ceasefire slated to take effect on July 11. Hostilities paused across the country, but as the Associated Press (AP) reported on the eve of the agreement, “the spirit of truce was the last thing to be observed in Belfast,” a Northern Irish city marked by sectarian divisions between the Protestant majority and the Catholic minority. On July 10 alone—a day now known as Belfast’s “Bloody Sunday”—an outburst of street violence claimed the lives of 16 people and destroyed more than 160 homes.

As a general rule, Irish Protestants at the time tended to be unionists loyal to the British crown. Catholics typically supported the nationalist, or republican, push for an independent Irish state. Though Northern and Southern Ireland (separate political entities created by the partition of Ireland in May of that year) were home to followers of both religious denominations, Protestant unionists tended to outnumber Catholic republicans in the north and vice versa in the south and west.

Heather Jones, a historian at University College London, explains that the “division between unionist and nationalist mapped onto existing historic religious differences in Ireland that dated back to the religious wars” of the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. Alan F. Parkinson, author of Belfast’s Unholy War: The Troubles of the 1920s, adds that Northern Ireland had a “radically different demographic composition” than the south, with close to 70 percent of residents identifying as Protestants “of British stock.”

Ironically, says Jones, “the different views on self-governance between unionists and nationalists in Northern and Southern Ireland in this period stemmed from the same roots—the rise of nationalism across Europe in the late-19th century and the spread of populist beliefs in nationalist ideals and demands for nation-states.”

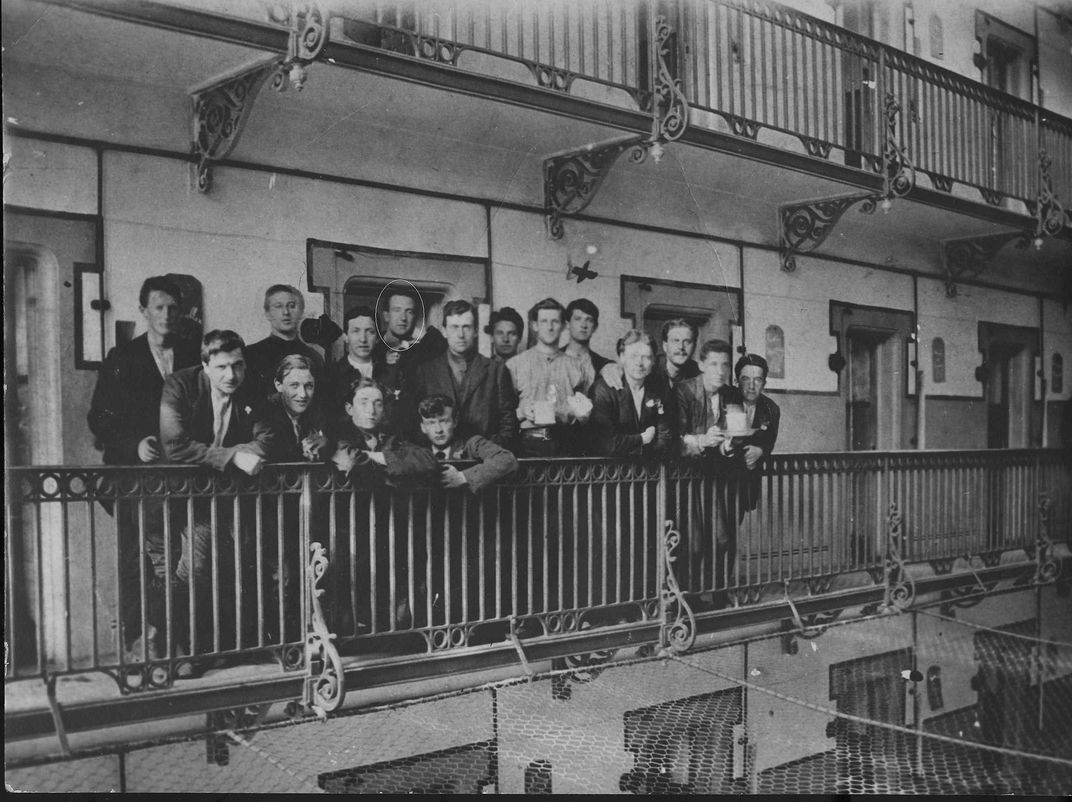

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d7/71/d771352c-8050-4b05-a480-e2a4b36ebde8/outside_the_london_and_north_western_hotel_in_dublin_april_21_1921.jpeg)

In Belfast, IRA attacks on police often sparked harsh reprisals against Catholics who found themselves unprotected by the British government. There, the truce’s promise of peace attracted suspicion. As Parkinson writes in Belfast’s Unholy War, unionists feared that republicans “were merely using the [ceasefire] as a breathing-space and an opportunity to redeploy [IRA] forces from the south and west in the north.” Unionists also expressed concern that the truce would negate the results of partition, forcing Ireland’s reunification and “undermin[ing] their security and identity” as loyal British citizens, says Jones.

According to Parkinson, “The cruel irony of the July Truce and the de-escalation of violence elsewhere in Ireland was that it heralded a particularly vicious summer orgy of violence in Belfast.”

Of these attacks, none was more deadly than Bloody Sunday—the day with the highest death toll of the entire Irish War of Independence.

The tragedy, Jones adds, “made clear the deep sectarian tensions that ran as fault lines through the new Northern Ireland and the failure of the new Northern Irish government to protect its Catholic minority—issues that would recur for the rest of the 20th century.”

**********

First claimed by England in 1171, when Henry II declared himself “Lord of Ireland,” the island nation merged with Great Britain to form the United Kingdom in 1801. Relations between these ostensibly united dominions were often uneasy, and the British government’s response to the mid-19th century Irish potato famine—ineffective at best and malevolent at worst—only exacerbated the tension.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the “home rule” movement—which advocated for the creation of a devolved Irish parliament within the U.K.—gained traction, particularly among nationalists. (Protestant loyalists, fearful that home rule would translate to “Rome rule,” with a Dublin-based parliament dominated by Catholics, advocated to maintain the status quo.) The outbreak of World War I in 1914 suspended home rule’s implementation, but as the conflict dragged on, some nationalists became increasingly radicalized.

On April 24, 1916, around 1,500 armed nationalists seized control of Dublin, occupying the city center for six days with the goal of establishing an independent Irish Republic. The British quickly—and brutally—put down the so-called Easter Rising, executing its leaders in a show of force that galvanized support for the republican cause among the horrified Irish public. As John Dillon, a moderate Irish nationalist who’d previously promoted devolution (the transfer of power from a central to local government) over independence, told his fellow British and Irish members of Parliament in May of that year, “You are washing out our whole life-work in a sea of blood.”

Divisions between nationalists and unionists, and by extension Ireland and Great Britain, came to a head in January 1919, when radical nationalists associated with the Sinn Féin political party convened a clandestine, separatist Irish parliament called Dáil Éireann. The IRA first mobilized that same month, officially marking the beginning of the Irish War of Independence.

Crucially, the conflict played out differently in the 6 counties that today constitute Northern Ireland and the 26 that make up the Republic of Ireland. In the early months of the war, says Jones, the north was “relatively quiet compared to the rest of the island,” where violence between IRA forces and British police—including paramilitary units that carried out reprisals against Irish civilians—escalated as nationalist politicians made significant electoral gains across the south. Between 1917 and 1921, the guerilla war claimed more than 1,000 lives in the southern province of Munster; another 300 or so were killed in Dublin.

Brewing discontent in the north heightened over the course of 1920. That summer, unionist mobs in Belfast drove thousands of Catholic shipyard laborers, as well as Protestants who tried to support them, out of their workplaces. According to the Irish Times, these unionists feared “that IRA violence was creeping northward” and took umbrage at the “increasing economic prosperity of the Catholic middle-class,” as well as Sinn Féin’s recent election success. Faced with rising sectarian disagreements in the north, also known as Ulster, and continued violence in the south, the British government suggested a compromise that it hoped would end the war: namely, partitioning Ireland into two territories, each with their own devolved parliament. Both newly created entities would remain in the U.K.

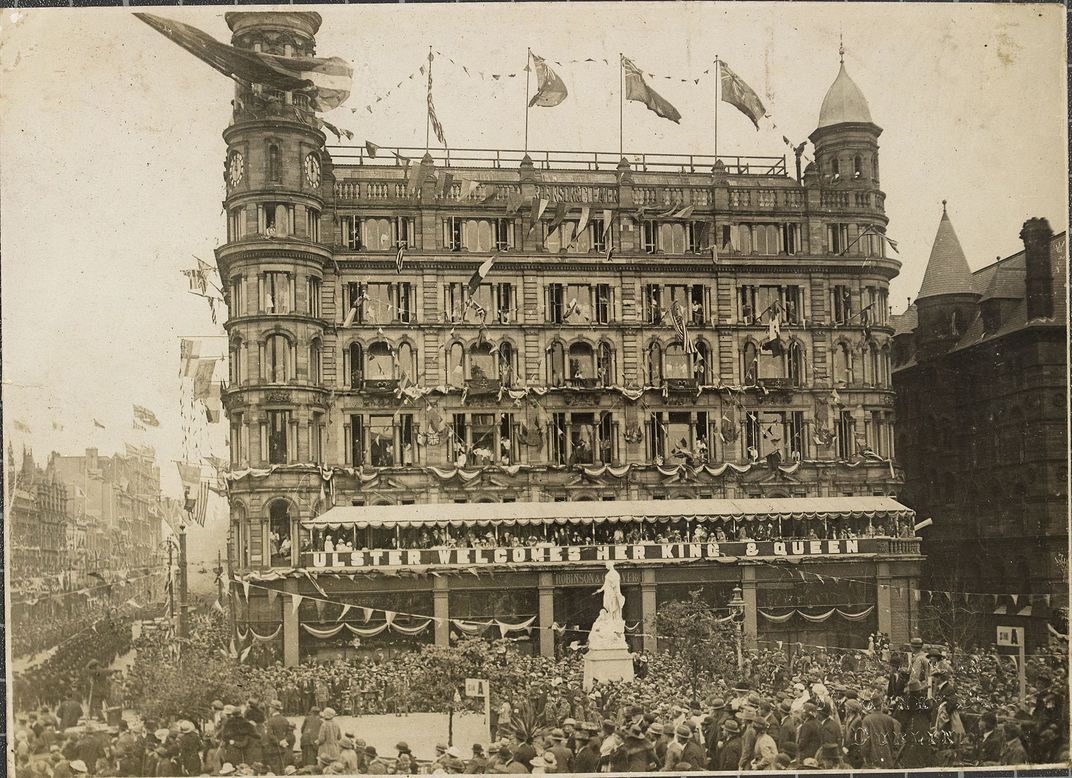

Though Ulster unionists had previously rejected calls for home rule, they now became its most ardent supporters. Northern Ireland’s predominantly Protestant residents elected a unionist government, and on June 22, 1921, George V formally opened the Belfast-based parliament. Nationalists in the south, on the other hand, effectively boycotted the Dublin-based parliament, quashing any hopes that partition would bring the guerilla war to a close.

As former British prime minister Herbert Asquith observed, the Government of Ireland Act gave “to Ulster a Parliament which it did not want, and to the remaining three-quarters of Ireland a Parliament which it would not have.”

**********

According to Parkinson, the events of Bloody Sunday were “precipitated indirectly” by the opening of Northern Ireland’s first parliament and more directly by a July 9 IRA ambush that left one police officer dead and at least two others seriously wounded. Though the July 11 truce was set to bring peace to the war-weary island in just a few days, Belfast-based nationalists and unionists alike were skeptical of the agreement.

“With Ireland already partitioned, there were unionist fears that the peace talks scheduled between the British and Irish Republican leaders to follow the ... truce might row back on the partition decision,” Jones explains. To unionists, partition represented the “safeguarding [of] their British identity into the future.” Nationalists, meanwhile, engaged in heightened violence in the days leading up to the truce, “probably wanting to make a show of local strength before” the ceasefire took effect.

Other factors contributing to the outbreak of violence on July 10 were a relaxed curfew associated with the truce and an upcoming annual celebration held by members of the Orange Order, a Protestant—and deeply loyalist—fraternal organization. Thanks to the so-called Orangemen, “Belfast had always been volatile in July,” wrote Kieran Glennon, author of From Pogrom to Civil War: Tom Glennon and the Belfast IRA, for the Irish Story in 2015, “... but [Bloody Sunday] was violence intensified and militarized on a scale not seen before.”

One local IRA fighter, Sean Montgomery, later claimed that he and his comrades received warning of an impending police raid late on July 9—the day the truce was announced. The IRA sent 14 men, including Montgomery, to respond to the threat; in the ensuing gunfight on Raglan Street, a single IRA shooter killed one policeman and seriously wondered two others.

For Belfast’s unionist community, the timing of the ambush served as “evidence that the IRA’s offer of a ‘truce’ was meaningless,” says Parkinson. Unionist retribution for the attack quickly followed. The next day, reported the AP, “a three-fold fight between [nationalist] Sinn Fein and Unionist snipers and Crown forces” broke out, with a “fierce and savage spirit animat[ing] the factions throughout the whole day and evening.” By the morning of the day of the truce, 16 people were dead, including 11 Catholics and 5 Protestants.

Combatants wielding machine-guns, rifles, pistols and hand grenades clashed on Belfast’s streets, in many cases indiscriminately injuring or killing passersby. According to the nationalist Irish News, one of the day’s first victims was 21-year-old Alexander Hamilton, a Catholic World War I veteran who “merely glanced round the corner of Conway Street when a unionist sniper at the … end of that thoroughfare sent a bullet through his head.” Snipers similarly targeted 70-year-old Bernard Monaghan and 56-year-old William Tierney, both Catholics reportedly shot in or near their homes. (Shooters often chose their targets randomly, assuming victims’ religious and political affiliation based on whether they lived in predominantly Catholic or Protestant neighborhoods.)

Two other Catholics—35-year-old James McGuinness and 28-year-old Daniel Hughes—lost their lives while attempting to bring their children home to safety. Hughes’ wife later told the Irish News that she saw “members of the Crown forces fire point blank at him and almost blow his head off.” The nationalist newspaper added, “She said to the man who fired the fatal shot ‘You have killed my husband!’ but he would not look her in the eye.”

Among the day’s Protestant victims were two young boys: 12-year-old William Baxter, who was shot while walking to Sunday school, and Ernest Park, who was around the same age and killed as he was carrying a kitten back to his neighbor’s house. Both were probably targeted by the same nationalist sniper.

In the Catholic-dominated neighborhood of Falls Road, a crowd of a few thousand unionists armed with “petrol, paraffin, rags and even small bundles of wood” made a “sudden and terrifying rush” for Catholic-owned homes and businesses, according to RTÉ. Authorities needed at least 14 fire engines to extinguish the blazes, which destroyed more than 160 buildings in Catholic districts. Elsewhere in the city, passengers traveling via tram were forced to take cover from passing bullets by huddling on the cars’ straw-covered floors.

On the night of July 10, scores of wounded crowded Belfast’s hospitals. One victim who survived the initial attack lingered for months, only succumbing to his injuries the following April.

“Belfast's Bloody Sunday,” says Parkinson, “proved to be the bloodiest 24-hour spell of violence during this two-year period of Northern disturbances.” But the carnage was far from over: On July 11, in the hours before the truce took effect at midday, three more were killed, among them a 13-year-old Catholic girl named Mary McGowan.

The events of Bloody Sunday underscored authorities’ inability—or, in many cases, unwillingness—to protect Belfast’s minority Catholic population. As Jones points out, “The police and the special security forces set up to support the new northern regime were overwhelmingly unionist and favored partition. … [I]ndeed, there was serious collusion in some incidents between police force members and attackers.”

Despite making up just a quarter of Belfast’s population, Catholics constituted over two-thirds of the roughly 500 people killed in the city between July 1920 and July 1922. They were “very vulnerable to retaliatory violence for IRA attacks on Protestants living in rural areas along the new border and upon the police, as well as to sectarian attacks,” says Jones, and bore a disproportionate brunt of the bloodshed.

Disturbances continued sporadically in the months following Bloody Sunday, with the “most sustained and heavy violence” occurring between November 1921 and July 1922, when the IRA was actively working to undermine partition and the northern regime, according to Parkinson. The region only experienced relative peace following the enactment of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, which designated the Irish Free State as a self-governing dominion within the British Commonwealth and upheld the border between it and Northern Ireland.

Internal disagreements over the treaty’s terms soon prompted the outbreak of the Irish Civil War, dividing the nationalist movement into pro- and anti-treaty factions. As infighting overtook the south, says Jones, “Northern Ireland stabilized and sectarian violence dramatically reduced.” (The Irish Free State adopted the new name of Éire, or Ireland, in 1937 and officially left the British Commonwealth in 1949.)

“Ultimately, the outcome of 1921 was two Irelands: a Northern Ireland remaining within the U.K. with a Catholic minority and an independent 26-county Ireland with a Protestant minority,” adds Jones. “Of Ireland’s two new minorities, the northern Catholic one ultimately fared worse,” with members eventually finding themselves at the center of a roughly 30-year conflict known as the Troubles.

**********

Belfast’s Bloody Sunday never achieved the infamy of Ireland’s other “Bloody Sundays”: British forces’ massacre of 14 civilians attending a Gaelic football match in Dublin on November 21, 1920, and British paratroopers’ killing of 13 Catholic civil rights demonstrators in Londonderry on January 30, 1972. Even in the immediate aftermath of the violence, the day’s events were overshadowed by the July 11 truce.

“The truce was a moment of celebration and optimism for much of the island’s nationalist population and saw an end to the War of Independence fighting between the IRA and British forces,” says Jones. “... The ongoing violence in Northern Ireland differed from the fragile peace that emerged on the rest of the island for the remainder of 1921. In Britain, too, the focus of public opinion was on the truce, not Belfast.”

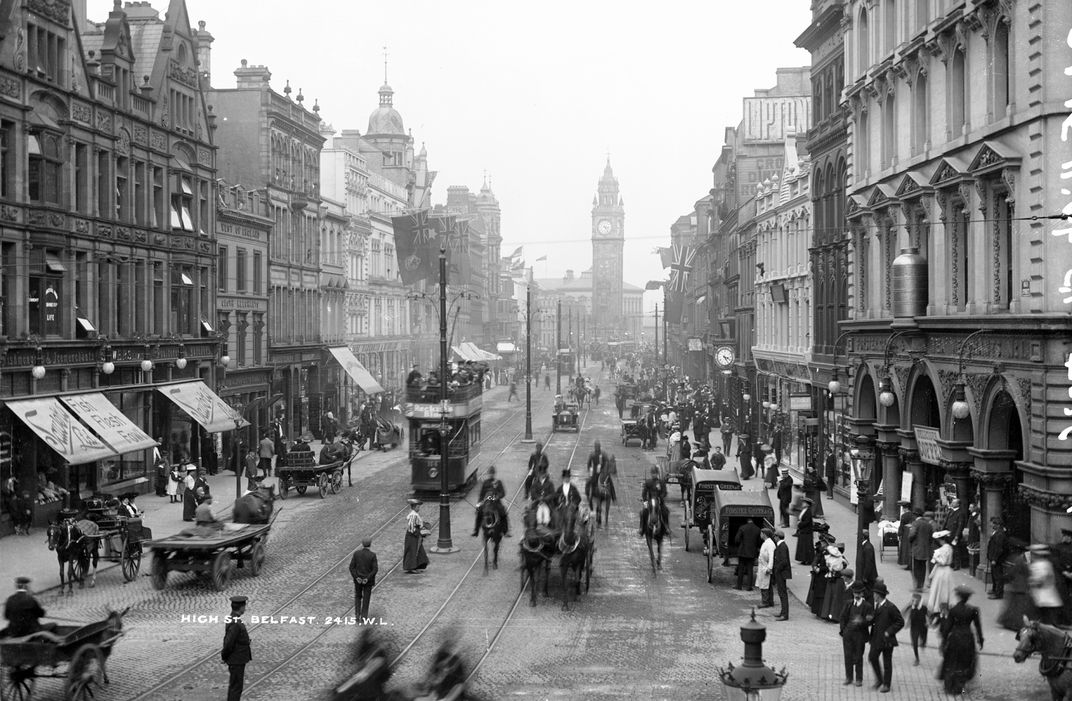

Far from acting as a microcosm of the broader Irish War of Independence, Belfast’s Bloody Sunday instead offers an example of how differently the conflict unfolded in Ireland’s north and south. Belfast was, in many ways, unlike the rest of the Ireland: “industrialized, prosperous, a city with a Protestant and unionist majority population and very close geographical connections with Britain,” per Jones. Though unionists lived across the island, they were a “largely dispersed population, … too weak to fight [Irish independence] politically or militarily” outside of the six northern counties.

In the south, most of the deceased were IRA or British forces. In the north, the majority of victims were civilians, including women and children caught in the crosshairs of random gunfire. As violence faltered in the south in the summer of 1921, unrest skyrocketed in the north; a year later, this trend reversed once again as civil war engulfed the southern-centric nationalist faction.

Today, says Jones, Ireland is a far more secular place than it was 100 years ago. “[T]here is a greater awareness of everything the different peoples of the island have in common than in the past and greater respect for difference,” she says. Still, with the specter of Brexit threatening to spark violence in Northern Ireland once again, echoes of the region’s not-so-distant bloody past continue to resonate.

“There are certain lessons to be learned [from] what happened 100 years ago, not only on Bloody Sunday but in other cases of senseless, tit-for-tat, sectarian killings in what I have called an ‘unholy’ war,” Parkinson concludes. “Uncertainty over the region's political future—as illustrated by the recent furor over Brexit and criticism of a ‘border’ in the Irish Sea—have been exploited by the unscrupulous, as they were in the past, and cast shadows over Northern Ireland’s political future.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)