When Paul Koudounaris visited Los Angeles’ North Central Animal Shelter one sunny afternoon in 2011, he didn’t intend to adopt the feline who would go on to become the inspiration for what is almost certainly the most unique cat history book ever published. Instead, the writer and photographer had come to pick up another cat, only to dejectedly discover that his would-be pet had just been adopted by someone else. But as he headed for the door, a striped paw reached out from a wall of cages and caught his shirt. It belonged to a six-month-old brown tabby whose intent green eyes immediately communicated to Koudounaris that she was always meant to go home with him.

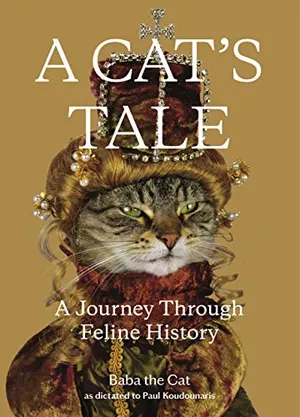

Baba, as Koudounaris called his new friend, became not only a beloved companion, but the narrator and model for his new book, A Cat’s Tale: A Journey Through Feline History. Spanning thousands of years, from prehistory and ancient Egypt to the Enlightenment and the New World, the tome features the heroic, tragic, heartwarming and incredible stories of dozens of cats. Many of these characters, including Muezza (“Cherished”), the prophet Muhammed’s companion, and Félicette, a Parisian alley cat sent into space in 1963, are among the most famous felines to ever exist. Others led notable lives but had been all but forgotten until Koudounaris rediscovered them. In addition to depicting specific cats in history, the book also tells the sweeping story of Felis catus’ overall journey throughout various historical eras.

A Cat's Tale: A Journey Through Feline History

The true history of felines is one of heroism, love, tragedy, sacrifice, and gravitas. Not entirely convinced? Well, get ready, because Baba the Cat is here to set the record straight.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/76/2f/762f428e-d0f8-46a6-bdd0-e88536ba6f3c/roman_ch_3.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/77/0d/770d6ddf-1498-478c-99d7-cf5677a40562/cowboy2_billy_the_kitten_ch_6.jpg)

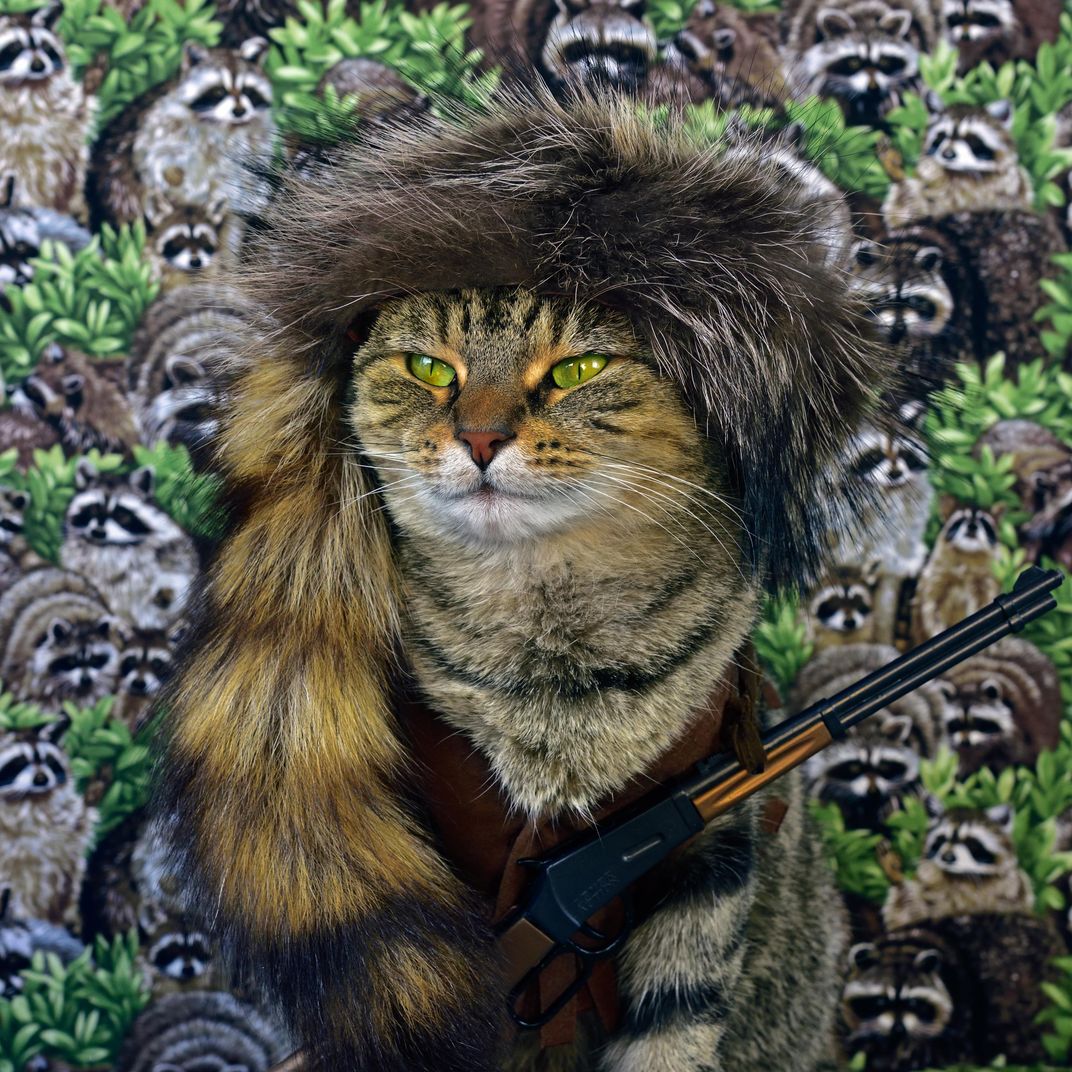

A Cat’s Tale is one of dozens of books about the history of cats. But the richly illustrated volume stands out because it’s actually told through the voice of a cat. Baba acts not only as narrator but also Cindy Sherman-like impersonator, appearing throughout the book dressed as historic individuals and caricatures. Her voice and visage make Koudounaris’ take on the subject truly singular, mimicking oral storytelling more than an academic treatise. As Baba declares in the first chapter, “We cats have been allies to humankind for a very long time, and while you have reserved the sobriquet ‘man’s best friend’ for the dog, I may now provide you reasons to judge differently.” Letting Baba carry the book also allows Koudounaris to make a larger point about the subjectivity of history, including which stories get told and whose point of view and agenda they convey.

“Ostensibly, it’s a feline history book, but it’s also at its heart something more: a challenge to history as being a homo-centric monologue,” Koudounaris says. Underneath Baba’s narratorial sass and charm is “a plea to include other species that have been left out of history,” he adds. “We’re all in this together, and we’re all connected.”

The idea for the book, like the adoption of Baba herself, came about through a series of auspicious coincidences. Like any doting cat owner, Koudounaris enjoys taking pictures of Baba. Over time, his photos became more elaborate, incorporating background drops, lights, and teddy bear and doll clothes.

As Koudounaris, an art historian and author who specializes in the visual culture of death, coordinated increasingly complex photoshoots, he began work on what he thought would be his next book: an exploration of pet cemeteries around the world. While researching the new project, however, he started accruing an unwieldy number of stories about amazing yet all-but-forgotten historic cats. Koudounaris learned of an army tomcat named the Colonel, for example, who was stationed at San Francisco’s Presidio in the 1890s and was said to be the best mouser the army ever had. He knew he’d never be able to fit all these gems into a book about pet cemeteries, and in pondering a solution, he came up with the idea for A Cat’s Tale—a book that would highlight the fascinating history of cats in general by putting Baba front and center.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/97/6597f09c-16da-411a-82c8-4cb4ffa7145c/cardinal_richelieu_ch_5.jpg)

“It was more than just a book, it was a part of the continued process of bonding with my cat,” Koudounaris says. “It’s feline history, it’s cosplay, and underneath it, it’s a love letter to all the cats in all our lives.”

Work on the book entailed two distinct approaches: finding and making appropriate costumes for Baba and combing through archives, libraries and other sources to piece together an exhaustive history of cats and our place in their lives. Creating the right costume proved to be the most challenging aspect of the photography part of A Cat’s Tale. At first, Koudounaris relied on eBay, flea markets and specialist vintage doll meetups. These hunts turned up everything from mini-17th century Puritan garb to a cat-sized Uncle Sam outfit, all of which Koudounaris tailored to fit Baba’s cat anatomy.

When some of the photographer’s visions proved too particular or complex to execute, he hired a friend, Desirae Hepp, who works on costumes for films. To craft samurai armor to illustrate a Japanese folktale about a military noble who called upon a famous cat to help dispose of a monstrous rat, Hepp repurposed an old wicker placemat; to fashion cat-sized Viking armor, she used a deconstructed human-sized helmet. “She’s a creative genius who likes weird projects,” Koudounaris says.

Dressing Baba and getting her to pose and assume the perfect facial expression was surprisingly easy. “Amazingly, like 99 percent of the time, she’d get exactly what I want,” Koudounaris says. Sometimes, she’d even nail it on the first shot. “With the Andy Warhol one, I did a test photo and was like, ‘Oh, that’s good—got it,’” he recalls.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/11/2c/112cfb7f-d73f-40d6-afab-7e05be7c7b73/andy_warhol_ch_6.jpg)

Research took Koudounaris across the country and world, from Wisconsin to Massachusetts and France to New Zealand. Once he began to look, stories popped up everywhere. In Tokyo, for instance, he researched the history of Maneki-Neko, the 17th-century Japanese cat who inspired the now ubiquitous raised-paw good luck cat. Back in California, he delved into the story of Room 8, a grey tabby who appeared at a Los Angeles elementary school in 1952 and stayed for 16 years, becoming the school’s mascot as well as the subject of a biography, TV specials and hundreds of fan letters.

One of Koudounaris’ favorite discoveries, though, was the Puss’n Boots Award, a long-lost prize given out by a California cat food company between 1950 and 1960. The first recipient was a black cat named Clementine Jones who made national headlines after she walked from Dunkirk, New York, to Aurora, Colorado, in search of her human family, which had moved and left her behind with relatives. Her family knew it was Clementine because, among other distinguishing traits, she possessed a single paw with seven toes—an extreme rarity. “Over a decade, [the company] gave out hundreds of these medals, and all these wonderful stories would be written up in all the local newspapers,” Koudounaris says. “Up until the 1950s, cats were really second-grade animals to dogs, but that medal alone really changed American perception of cats.”

Cats have now firmly established themselves as pop culture icons and favorite pets. But in Koudounaris’ view, they still have much to say, if only we would give them the chance. Both Baba and Koudounaris end the book with an appeal to readers: to live history through the making with the special cat that shares their lives.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9d/e2/9de20442-cd60-48c0-8f8f-5e816b374c04/parisian_lady_ch_5.jpg)

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(305x148:306x149)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a0/15/a015251a-6a1d-449c-bf13-8c1c129c4cc5/egypt_kitty_mobile.jpg)

:focal(594x274:595x275)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/95/db/95db799b-fddf-4fde-91f3-77024442b92d/egypt_kitty_social.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)