History Forgot This Rogue Aristocrat Who Discovered Dinosaurs and Died Penniless

Now fallen into shadow, the Romania-born Baron Franz Nopcsa was a groundbreaking scientist, adventurer — and would-be king

Sacel Castle, in a part of Transylvania known locally as the Land of Hateg, is not open to the public, but Dacian Muntean, my guide, has arranged for us to get in. I’ve seen the entryway in old photographs—Persian rugs, a piano, a grand staircase lit by a round, cathedral-like window of leaded glass.

That is nothing like what I find before me. If it weren’t for the window, I wouldn’t recognize it at all. Swallows fly through where the panes once were and sunshine pours down on stairs now covered in rubble. Two huge ceiling beams have fallen and are lying askew on the landing. Others are detached on one side and hang down precariously.

“Is it safe to go up?” I ask Dacian. He considers. “Yes,” he says. “I think so.” A dog with matted fur follows us, along with her lame puppy. It’s clear that this crumbling, abandoned castle is their home. They scamper over the rubble; one stops to pee on a pile of debris.

Upstairs, every window is gone. The floorboards are rotten. The walls are pockmarked with holes where treasure seekers, hearing a legend of hidden gold inside, have punched through. We come into what was once a stately library. Dacian points at a bay window. A breeze blows through the sockets. “I like to imagine him here reading,” he says. In the corner, an ornate wrought-iron spiral staircase leads up to nowhere, and I see light coming through a hole in the roof.

The castle was once the family home of Baron Franz Nopcsa von Felso-Szilvas, an Austro-Hungarian aristocrat born in 1877. Baron Nopcsa was a notorious figure in his day. A wild genius with a flair for the dandyish and the dramatic, he was an explorer, spy, polyglot and master of disguise. He crossed the Albanian Alps on foot and befriended local mountain men, sometimes involving himself in their tribal feuds. Once, he was nearly crowned King of Albania. It was said that he would disappear for months at a time only to arrive for polite tea at posh European hotels dressed as a peasant. Along with a younger man whom he called his secretary, he traversed swaths of the Balkans on motorcycle. He kept up years-long correspondences with famous and learned men all across Europe. Later in his life, he was known for chasing villagers from his estate with a pistol.

It is easy for the intrigue and romance of Nopcsa’s exploits, and the manner of his tragic death, to obscure the quieter fact that the baron was one of the great scholars and scientific minds of his time—and was largely self-taught. He was one of the first scientists to look at fossilized dinosaur bones and see a living, social creature. In fact, he was a staunch believer in the evolutionary relationship between birds and dinosaurs, decades before the idea became widely accepted among paleontologists. His overall contributions to the field have led some to call him the forgotten father of dinosaur paleobiology. “Nopcsa was asking questions nobody else was asking,” says David Weishampel, a paleontologist at the Center for Functional Anatomy and Evolution at John Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Nopcsa was equally brilliant as a structural geologist. While most of the scientific community still scoffed at the theory of continental drift, he provided some of the strongest evidence for such movement. He mapped the geology of Albania and became one of the country’s foremost ethnographers and historians. “It would be no exaggeration to say that he knew the country and its people better than any foreigner of his day,” says Robert Elsie, a scholar of Albania and the translator and editor of Nopcsa’s memoirs, published in English in 2014.

Over his career, Nopcsa published several tomes and more than 150 scientific papers. Yet his name barely appears in textbooks. No historical plaque adorns any of the places he lived or taught. Even his grave is unmarked.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bd/e7/bde727a2-89d4-48f1-a75f-7161c286639e/julaug2016_b04_dinobarontransylvania-wr-v1.jpg)

**********

Nopcsa was born to a wealthy noble family, the eldest of three children raised at Sacel. He had a typical upbringing for an aristocrat in a provincial backwater of an aging empire. At home he spoke Hungarian and learned Romanian, English, German and French. His father, Alexius, had fought in Mexico against Benito Juárez, in 1867, as a hussar in the army of Maximilian, Archduke of Austria and Emperor of Mexico. Later Alexius became a vice-director at the Hungarian Royal Opera, in Budapest. Nopcsa’s mother, Matilde, came from an aristocratic family from the nearby city of Arad.

In 1895, Nopcsa’s sister Ilona was walking along a riverbank near the family home when she found an unusual-looking skull, and she brought it to her teenaged brother. It soon became his obsession.

The skull belonged to a previously undiscovered duck-billed herbivore from the dusk of the Mesozoic, around 70 million years ago, and was buried in sediment before a mass extinction that would wipe out three-quarters of all plant and animal species on earth. Crushed by geological forces, the skull was in terrible shape.

In the fall, Nopcsa entered the University of Vienna and took the skull with him. Like a cat with a gift rat, he presented it to his professor, a famous geologist, expecting him to take it from there. But the professor sent Nopcsa back to Transylvania and told him to figure it out for himself. Whether it was lack of interest or funding or the cunning strategy of a master teacher, it was the making of a great scientist.

In the library of Sacel Castle, Nopcsa taught himself geology, physiology, anatomy and neurology. He wrote to scientists all over Europe asking for more books. At the time, very few European dinosaurs had been found. Unable to compare his fossils with others, he relied on his imagination. Working along the river strata, he began to excavate, preparing the fossils he found with homemade glue. From the tiniest scratch on the fossilized braincase, he speculated about the relationship between the pituitary gland, which regulates growth, and an organism’s size, applying what he’d learned of soft tissue and blood circulation. Drawing on the jaw mechanics of lizards and alligators, he rearticulated his dinosaur’s jaw and envisioned its musculature. In this, he was breaking new ground—comparing his dinosaur to living things.

Later, he would look at the pelvis and hind limbs of crocodiles to understand the mechanics of how running flight may have evolved in early birds. From watching birds themselves, he recognized brooding patterns in dinosaur nests, reasoning that since the hatchlings were too undeveloped at birth to defend themselves from predators, some dinosaurs must have parented their young. These ideas, too, were utterly new.

Nopcsa returned to Vienna and, at the age of 22, presented his work to the Austrian Academy of Sciences, one of the foremost scientific bodies in the world. His entry onto the international stage was anything but discreet. During his lecture, Nopcsa skewered the dinosaur classification system of a prominent scientist named Georg Baur with little concern for etiquette or empathy. His genius was clear, but so was his colossal talent for rudeness, which would shape his academic relationships throughout his life.

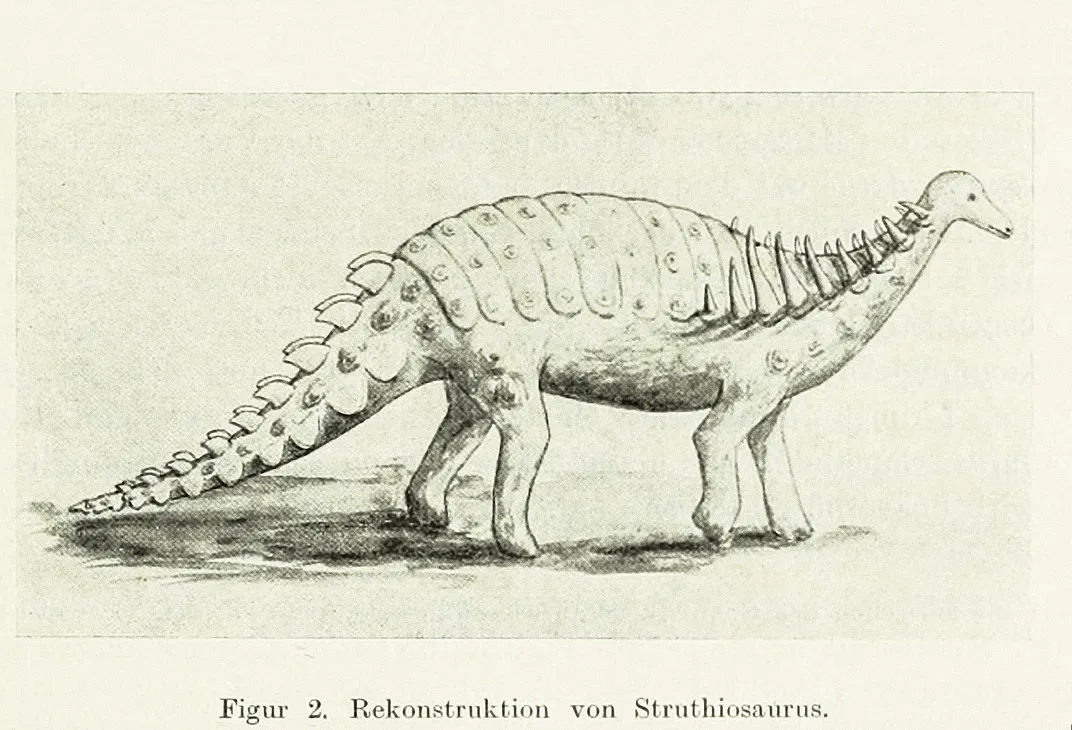

In time, Nopcsa would identify 25 genera of reptiles and five dinosaurs—the duck-billed Telmatosaurus transylvanicus, the beaked and bipedal Zalmoxes robustus, the armored Struthiosaurus transylvanicus and Magyarosaurus dacus and the meat-eating Megalosaurus. Four of these would become the “type specimens” of their species, the fossil blueprints against which all examples would be judged.

The Hateg dinosaurs turned out to be unique. They were unusually small—in some cases nearly miniatures. Nopcsa’s titanosaur belonged to a family of massive sauropods reaching lengths of 100 feet and weights of 80 tons, yet M. dacus was the size of a horse. His Telmatosaurus was smaller than a crocodile. Others were roughly an eighth the size of their non-Romanian cousins. The question was, why?

The most obvious possibility was that Nopcsa had found juveniles. Yet he didn’t believe this to be the case, and he was determined to prove otherwise. Certain bones grow together with age, and a good comparative anatomist, which Nopcsa was, can tell the developmental age of an organism by examining these sutures—so long as he has the right bones. But paleontologists don’t get to choose their bones, and Nopcsa’s Transylvanian miniatures presented either the wrong ones or were crushed beyond analysis. Looking for other ways to discern age, Nopcsa began to examine slices of bone under a microscope to study cell structure.

“Bones grow from the inside out, like trees,” explains Weishampel. “It’s possible to guess an age by counting the rings.” Today this method is known as paleohistology, and Nopcsa’s significant early contributions, particularly in determining which bones are most useful for analysis, remain largely uncredited, according to Weishampel.

Certain that his dinosaurs weren’t juveniles, Nopcsa looked to explain why they seemed unable to grow beyond a certain size. And he began to formulate the argument that Hateg was once an island—another claim supported by research after his death. Hateg Island’s environmental pressures, he concluded, limited the dinosaurs’ development.

“Islands are unique places, where biology gets a free hand,” says Weishampel. “Large animals tend to get smaller—for example, the dwarf elephants of Malta, hippos in the Mediterranean.” And, as it happens, the dwarf dinosaurs of Transylvania. The theory is that fewer food options lead to the success of animals with smaller anatomies. “And small animals,” Weishampel continues, “tend to get larger, like Komodo dragons, boas and tortoises in the Galápagos.” Nopcsa correctly identified the first set of conditions, and the second, scientists now speculate, can be explained by the idea that animals whose body sizes are held in check by predators on large landmasses tend to expand on an island with fewer of them. Nopcsa’s theory of what he called “island insularity” developed into what scientists now know as the “island rule.”

But though Nopcsa possessed many talents, he also possessed a private affliction, the symptoms of which can be discerned in letters he sent to Arthur Smith Woodward, the famous geological curator of the British Museum. The two men corresponded more or less monthly from 1901 until Nopcsa’s death in 1933. Nopcsa’s tone is touchingly deferential no matter how close the men became: The baron never failed to address his elder as “sir.”

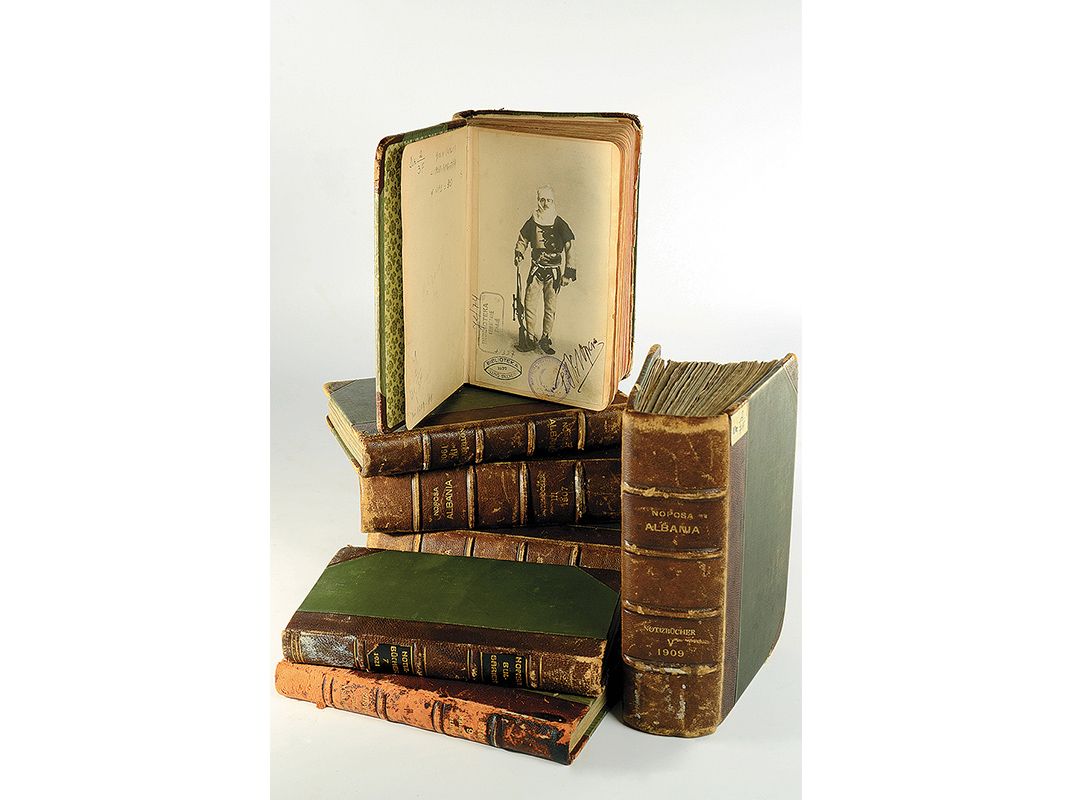

Leafing through the great cache of letters, each page preserved between sheets of plastic and bound in a dozen volumes now held in an archive at the Natural History Museum in London, you can see the places where Nopcsa’s customary scrawl becomes spidery, as though his thoughts were turning in on themselves. Once, in 1910, after Nopcsa failed to arrive in London for a meeting, Smith Woodward received a note instead from Nopcsa’s mother, the baroness. As if excusing a child from school, she explained that her son was unable to visit due to a recurring illness.

Nopcsa’s life continued to be punctuated by periods of extreme productivity, extensive fieldwork and prolific writing, but over time his illness worsened. He later referred to what devastated him as “shattered nerves.” Today we would likely call it manic depression.

**********

Even as Nopcsa was establishing himself as a scientist, he became enthralled by tales of Albania’s mountain tribesmen, whom he first heard about from a man thought to be his first lover, Louis Draskovic, a Transylvanian count two years his senior. Nopcsa soon determined to visit the mountains and study the land and the people there.

At the turn of the 20th century, fieldwork wasn’t funded as it might be today, with university grants or stipends. And in this fundamental way Nopcsa’s aristocratic status cannot be separated from his life as a scientist. He had social access and money for schooling. He met Smith Woodward through his parents, and his first geological foray into Albania, in 1903, was paid for by his uncle, a favorite courtier of Empress Elisabeth of Austria. In the years to come many of Nopcsa’s Albanian adventures were paid for by the Austro-Hungarian Empire itself, the fruit of a different kind of relationship: At some point Nopcsa began to work for the vast and crumbling empire as a spy.

Albania was then the buffer zone between Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire. As tensions rose in the run-up to World War I, the Austrian Imperial Council felt that it would be useful to have an accurate geographical and cultural map of the country. Nopcsa’s resulting studies and photographs documenting the country’s highland culture would become canonical for future ethnographers.

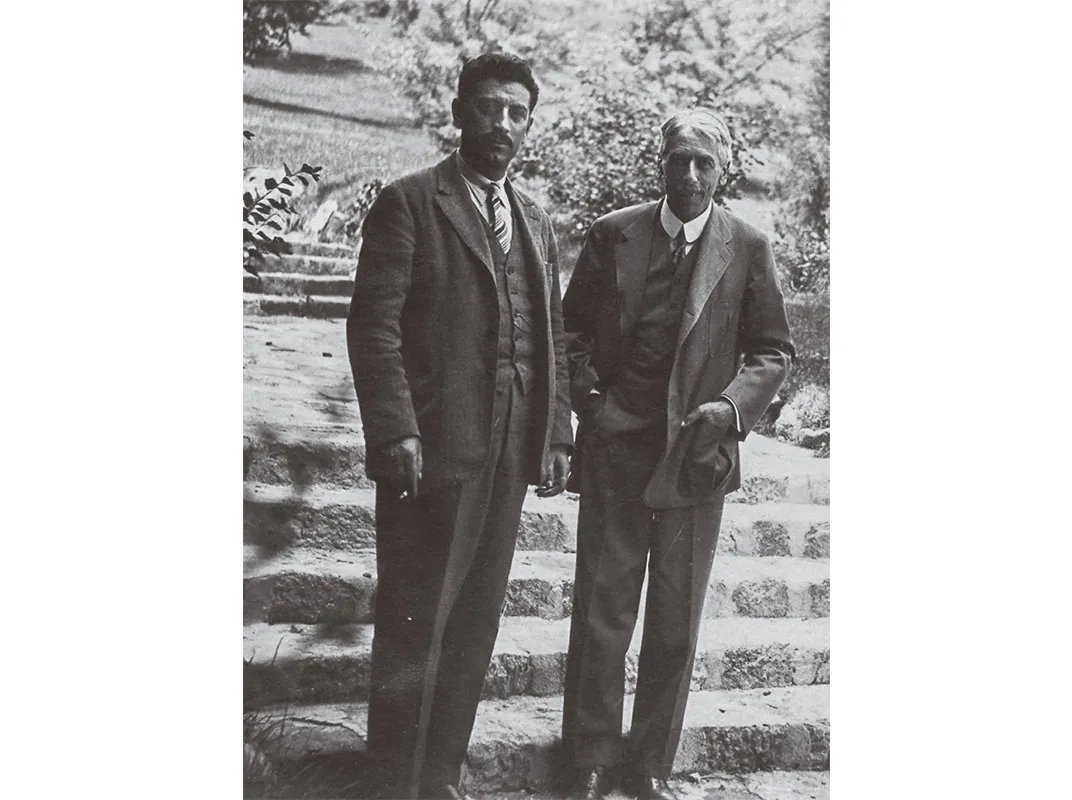

In 1906, while planning a trip, Nopcsa hired a young Albanian man to be his secretary. Bajazid Elmaz Doda was from a shepherd’s village high in the mountains. Nopcsa wrote in his journal that Doda was “the only person who has truly loved me” since Louis Draskovic. The feeling was apparently mutual. Nopcsa would later name a species of ancient turtle after Doda—Kallakobotion bajazidi, or “beautiful and round Bajazid.”

From the time they met until the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Doda and Nopcsa were often on the road. Nopcsa became fluent in local Albanian dialects and built friendships with the tribesmen. He was fascinated by their sense of honor. In a letter to Smith Woodward, he describes with great admiration witnessing a man take tea with the murderer of his son and saying nothing, because both were guests in another’s house—a feat of self-restraint, Nopcsa wrote, that no European gentlemen could have matched.

Meanwhile, Albania, held by the Ottomans for centuries, was becoming unstable. As the First World War approached, Nopcsa hoped to lead an insurgency of mountain tribesmen against the Turks. Europe’s “great powers” wanted to claim the country, and in 1913 they held a congress in Trieste where delegates from the Albanian tribes were assembled to discuss who should be made king of a newly independent Albania. Nopcsa, displaying a bit of colonial dash, put forth his own name. It was not an outlandish suggestion. The great powers were determined to install a European aristocrat, and by this time Nopcsa had spent years in Albania and had built deep ties. But the foreign office ultimately did not support him, choosing instead a German, Prince William of Wied. It marked the end of Nopcsa’s interest in politics.

“My Albania,” Nopcsa declared with great paternalism in a letter to Smith Woodward, “is dead.”

**********

Arriving in Deva, the city in present-day Romania where Nopcsa was born, you first notice the medieval citadel, which looms over the city from atop the gargantuan cinder cone of an ancient basaltic volcano. According to local lore, a woman was walled alive into the citadel’s foundation when it was built in the 13th century, to make it “stronger.” “People are superstitious here,” says Dacian, who is a great collector of legends. “The last time someone was ‘staked’ here was 2004.”

Dacian is in his late 30s, with long brown hair that makes him look more like a heavy-metal drummer than the head of a cultural restoration project. But his passion for Nopcsa is evident. Dacian is from Deva, too, and for him, the baron isn’t just a great and underappreciated scientist—he’s a hometown boy.

As a child growing up under the country’s autocratic Communist leader Nicolae Ceausescu, Dacian tells me, he visited Sacel Castle, then an orphanage. “Who owns this?” he would ask. “The people,” they said. “Yes, but who owned it before?” He got no more answer. As an adult, he began to do his own research, and for the past five years he and his partner, Laura Vesa, have worked ceaselessly to restore Nopcsa’s name in the place of his birth.

“Before we started working, no one in Deva knew who he was,” Dacian says. “Now, if you stopped someone on the street, they might say, ‘Oh, that’s the dinosaur man. He was a baron from here.’”

In the foothills beneath the citadel, houses with terracotta roofs line roads that meander like waterways. Goats and chickens wander around backyards, and shrines to Catholic saints decorate the street corners. As we thread through villages, Dacian tells whomever we meet—store owners, waitresses—about Nopcsa. It’s his vision that Nopcsa’s castle be restored and become a center for scientific research.

But Romania, though rich in natural resources, is poor in cash. Under communism the books in Nopcsa’s library were burned for political reasons, but now they’re burned for heat. So making the case for saving the castle is difficult.

In Hateg, we pull over at a roadside museum dedicated to the region’s fauna. The door is locked, but the village bartender has the keys. The place is about the size of a one-bedroom apartment. The bartender valiantly recites what he knows about the dinosaurs that once roamed here. There are casts of fossilized eggs and a couple of displays showing Balaur bondoc, a small, feathered theropod recently discovered in the area. On a shelf near the entrance sits a small collection of colorful clay dinosaurs made by village kids.

Later, we visit a building that locals hope will someday become a museum devoted to Transylvanian dinosaurs but is now filled, like the roadside attraction, with little more than some fist-sized rocks, a few casts of dinosaur eggs and posterboard displays. The mayor of the village arrives with a geologist from the University of Bucharest to give me a tour. The town has already installed, outside, a replica of M. dacus, Nopcsa’s dwarf sauropod. The museum-quality replica, the mayor explains, is anatomically correct to the last detail—and made by a Canadian artist at great expense. But a Kickstarter campaign was needed just to cover the dwarf sauropod’s shipping costs.

Dacian dreams that these small museums and posterboard exhibits will raise interest in the Land of Hateg, drawing visitors from other parts of Romania. He has put on exhibits about Nopcsa with borrowed photographs, made short documentaries for Romanian TV and translated hundreds of pages of the baron’s memoirs from German into Romanian. Last year, he and Laura wrote a major proposal that won Sacel Castle a place on a list of cultural sites to be funded by the government. So far no money has come, and the castle is disintegrating. But Dacian has no doubts he will succeed; he speaks of the restoration as a fait accompli. He is irrepressibly optimistic, signing all his emails “Sunny Days!” He imagines a Transylvania where village women can sell their embroidery at a fair price to tourists, where kids know their history and where Nopcsa is not forgotten.

There is no easy explanation for why Nopcsa has been overlooked for so long. In recent years, a loose international brotherhood of paleobiologists, Albanologists and LGBT activists has emerged hoping to earn him a more prominent place in history. Some point to Nopcsa’s sexuality as the reason for his persistent obscurity, and Dacian acknowledges that in a country as religious as Romania, the generally held belief that Nopcsa was gay (which the available evidence seems to corroborate) has been a hurdle in his campaign to restore the baron’s legacy. But Dacian is circumspect, maintaining that Nopcsa’s relationship with Doda could have been an intimate male friendship in keeping with the adventure books of the time, like those of Karl May, which Nopcsa loved. Dacian proposes something on the spectrum of Sherlock and Watson, Kipling and Gunga Din, a faithful manservant kind of thing. I introduce him to the term “bromance,” which he loves. “Yes,” he says. “A bromance.”

Weishampel, at Johns Hopkins, offers a broader perspective, remarking that Nopcsa was known by many of his colleagues to be gay, and that it seemed to cause little stir. For his part, it’s possible that the baron viewed himself less as a man on the margins of society than as a man above it. Paired with his eccentricities, however—like trying to be King of Albania, dressing like a shepherd, taking blood oaths to become brothers with Albanian tribesmen—he was, in a sense, fated to be an outsider scientist.

In the 1920s, the frontier of paleontology shifted to North America, as pristine fossil beds opened up to extensive research. “The great dinosaur rush out of Alberta changed everything,” says Weishampel. “And Nopcsa never visited the U.S. or Canada. While respected in Europe, his work never reached a critical mass.”

By then, Nopcsa’s revenues from his family estates had been lost in the aftermath of World War I, and with little money for research and his remaining family dispersed across Europe, Nopcsa began to sell his fossils. Meanwhile, scientific institutions, rather than gentlemen’s societies, began to take up the responsibility of preserving professional legacies, and Nopcsa, who rarely darkened the door of a classroom, had few academic advocates. His work began to fall into shadow.

On my last night in Deva, I watch a DVD of Lawrence of Arabia in Romanian that I found for $.75 in a grocery store. I’m suddenly struck by the similarities between Lawrence and Nopcsa. Lawrence, an archaeologist, was also in love with the past. Both men had been spies during World War I, conducting espionage under the auspices of scientific research—although, in the case of Nopcsa, you might say he was conducting scientific research under the auspices of espionage. Both mastered multiple languages and were able to infiltrate fiercely independent cultures: Lawrence, the Bedouin, and Nopcsa, the Albanian mountain men. Both took on tribal customs and dress and sought to lead insurgent forces against the Turks. Both were men of empire, and both were presumed homosexual during their lifetimes. Even littler things were similar. They were each obsessive motorcyclists. Lawrence died in a motorcycle crash, and Nopcsa demanded to be cremated in his motorcycle gear. But T.E. Lawrence became “Lawrence of Arabia”—and Nopcsa died in penury.

In my hotel room, I wonder if the comparison had ever occurred to Nopcsa—and if it had, what might it have felt like for him to fall short?

One spring morning in 1933, at age 55, Nopcsa wrote a final letter to Smith Woodward, apologizing for failing yet again to show up in London. The letter is written with his usual formality, but near the end he included a bizarre, gleeful, completely uncharacteristic and nearly nonsensical rhyming poem. Two weeks later, on the morning of April 26, having sold all of his fossils and his remarkable library for a pittance, Nopcsa woke up, sent the housekeeper out on an errand and then shot a sleeping Doda before turning the gun on himself. In a suicide note, he gave the reason for his actions as nervous collapse.

**********

Nopcsa and Doda were laid to rest in Vienna at exactly the same moment of the same hour, Nopcsa interred at the crematorium and Doda across the road in the cemetery’s Muslim section. Nothing marks Nopcsa’s grave. An ash tree has grown over Doda’s.

I had heard that the apartment they spent years in, at Singerstrasse 12, had been converted into a bank. None of the tellers have ever heard of Nopcsa, but stepping outside, I spot an old number plate behind scaffolding on the building next door. The bank, it turns out, is number 10.

A man wearing a fine suit is buzzed in next door at Singerstrasse 12, and I sneak in behind him. Everything on the ground floor is original, including the old iron and glass elevator. From Nopcsa’s obituary I know which floor the two men had lived on, and I go up.

The room where Nopcsa shot himself is today a real estate office. Through a row of large windows in what was once his Viennese library, morning light falls on the floor as it would have more than 80 years earlier. I wonder if I am the first person since before World War II to stand in that room knowing of Nopcsa’s final act.

It was said that Nopcsa conducted intellectual debates like Albanian tribal feuds. Even in his suicide note, he reserved a special place for Hungarian academics, whom he’d worked with unhappily years earlier during his only academic appointment, and demanded that the police prevent them from mourning him.

Regarding the disposal of his body, Nopcsa was emphatic. “I wish to be burned!” he wrote, using the harsher verb, verbrannt, rather than the softer language of being turned to ashes. The man who spent his life with bones from the past made sure to leave none of his own behind.