The History of Our Love-Hate Relationship With the Christmas Letter

How the “Dear Friends” missive started and how it has survived the Facebook age

:focal(2130x4385:2131x4386)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ae/78/ae782144-5dc0-499c-a27c-069c41893f6f/dec018_b07_prologue-web.jpg)

Shedd, Oregon. December 25, 1948. “Dear Friends,” wrote Marie Bussard, a homesick mother of three. “Now that Christmas is here again... we find that there is too much news to fit into a note on each card. We have borrowed this idea of a Christmas News Letter from our friends the Chambers and the Danns.”

So they’re the ones to blame.

Without realizing it, Bussard was among the pioneers of a new practice that spread across the postwar landscape in the 1950s and ’60s, as more people moved away from their hometowns. A year-end ritual we have learned to love and hate simultaneously, the holiday newsletter has always been Americanish—efficient, egalitarian and increasingly secular. It got a big boost in the 1960s when photocopiers made rapid reproduction widely available (as long as there was a solicitous secretary in the office to do the copying) and the U.S. Postal Service brought out the first-class Christmas stamp, encouraging more people to send holiday greetings. In the stamp’s debut year, 1962, post offices sold 1 billion, at 4 cents each.

To most of us, “Dear Friends” letters are highly disposable, but to a retired archivist named Susan B. Strange they’re keepers—a unique record of daily life. “These letters are about family,” she says. “So often, at least until recently, that has not been captured by historians.” Strange began collecting holiday letters in the late 1990s, and her personal trove of about 1,500 from 100 families—including more than six decades of news from the Bussard family—is now preserved at Harvard’s Schlesinger Library, a resource devoted to the history of American women, where you will also find the National Organization for Women’s statement of purpose, Ms. Marvel comics and a birth-control brochure titled “A Word to the Wives.”

It was women, after all, who wrote most of the family holiday circulars in the Schlesinger archive. Some were curiously specific: “Has anyone noticed that the recipe for cookies on the Quaker box has changed?” Some bragged about children. Others threw them to the wolves: “Philippe (13) is undeniably a teenager...he knows everything, his room is a mess, the most important thing in his life is his social life.” Some rhymed: “The snow has been flyin’. / St. Nick’s on his way. / It’s time for a Barbara / Communiqué.” And a few veered into the dangerous territory of politics. One included a 1940s verse imagining Franklin D. Roosevelt telling the Devil why he should be allowed into hell. “I ruined their country, their lives, & then / I placed the blame on my ‘9 Old Men.’”

Taken together, the emphasis, of course, is on the positive, and the great American talent for self-promotion is much in evidence. One study of holiday newsletters found that the leading topic was travel experiences. Weather was big. Also near the top: Mom and Dad’s professional accomplishments, the kids’ scholastic achievements and the family’s material possessions. At the bottom of the list were personal and work problems. Another published in 2007 documented a new fin de siècle syndrome: “busyness.” Analyzing about a half-century of newsletters, Ann Burnett of North Dakota State University saw an increase in the use of words such as “hectic,” “whirlwind” and “crazy.” Through their annual holiday letters, she says, people were “competing about being busy.”

The traditional Christmas card was considered a vulgar time-saver when it was first introduced in the 1840s, so perhaps it’s no wonder that almost as soon as newsletters appeared, they too became a punchline. In 1954 the Atlantic Monthly sneered that “no Christmas letter averages fewer than eighteen ‘!’s,’ ‘!!’s’ or ‘(!)’s’ per page.” Ann Landers, in her syndicated advice column, published complaints about the so-called “brag rags,” such as one first printed in 1968 asking why “normally intelligent people seem to take leave of their senses at Christmas.” Umbrage, of course, was taken. “How can you, in good conscience, encourage people to not share their happy news in holiday letters?” chided Pam Johnson, the founder of the Secret Society of Happy People. “We live in a popular culture that all too often makes people feel rotten for being happy and even worse for sharing it....Happy moments are good things that need to be shared more—not less.” As culture wars go, this was pretty tame, but an Emily Post Institute survey showed that Americans were sharply divided, with 53 percent approving of the holiday letter and 47 percent hating it.

The internet should have put an end to this oddly fascinating custom. Who needs a once-a-year family-fun marketing report when Facebook and Instagram can update friends and strangers every minute? But compared with social media’s beeping, hectoring fragments, a printed letter arriving in the mail—the stamp cost half a dollar!! sent from an actual place!! complete sentences!! touched by an actual person!! a real signature!!!—now seems like a precious human document, as valuable as an ancient papyrus. If only people weren’t too busy to read them.

* * *

Frosty's Family Tree

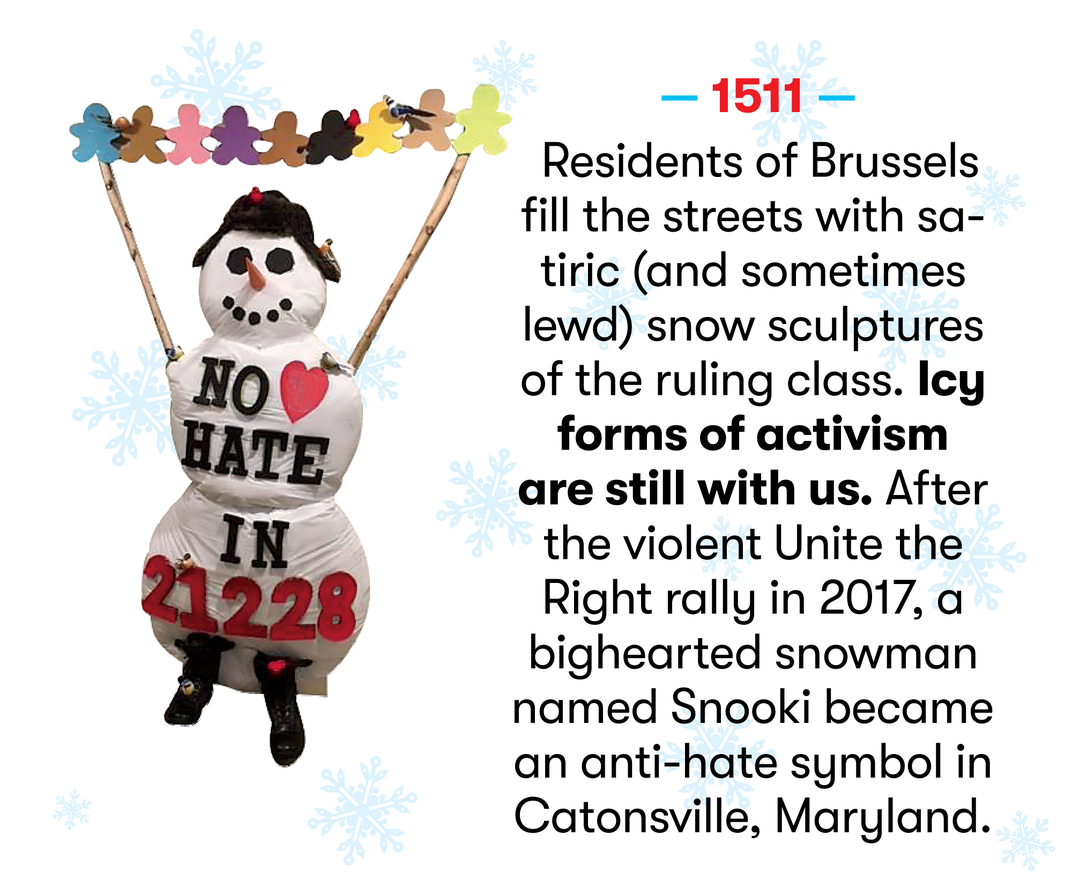

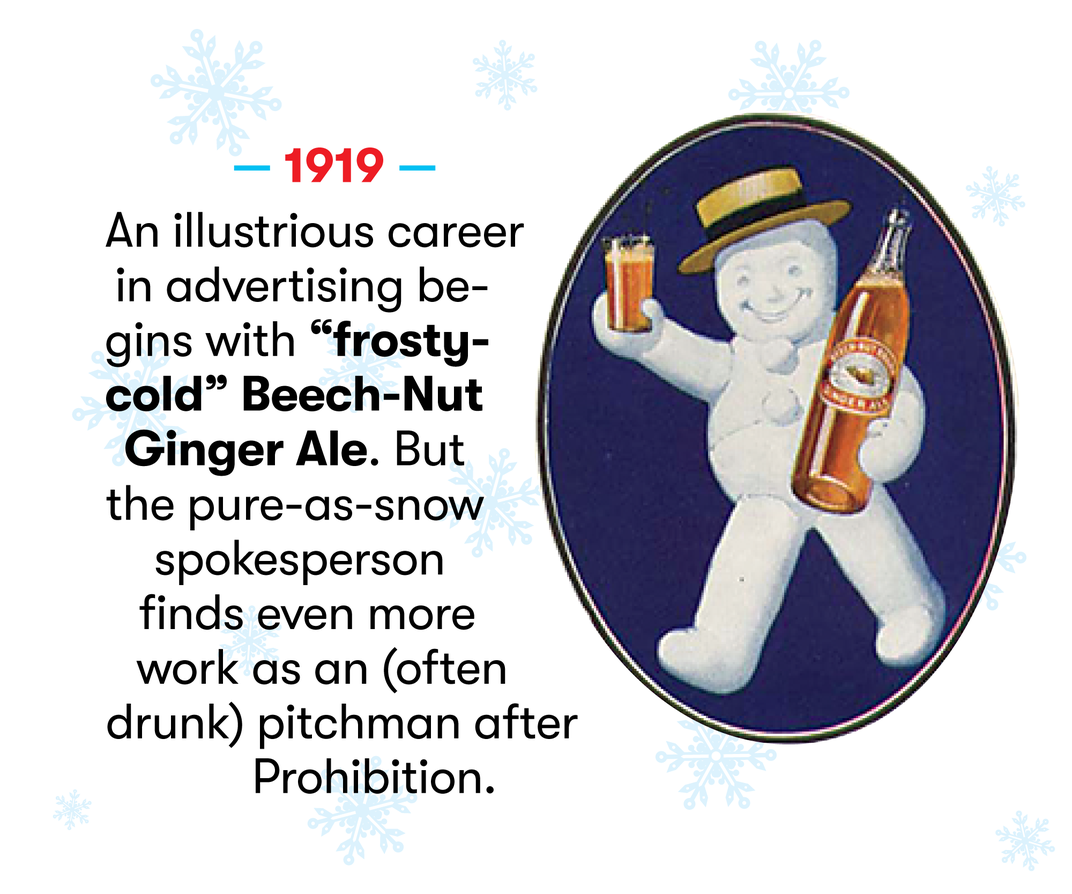

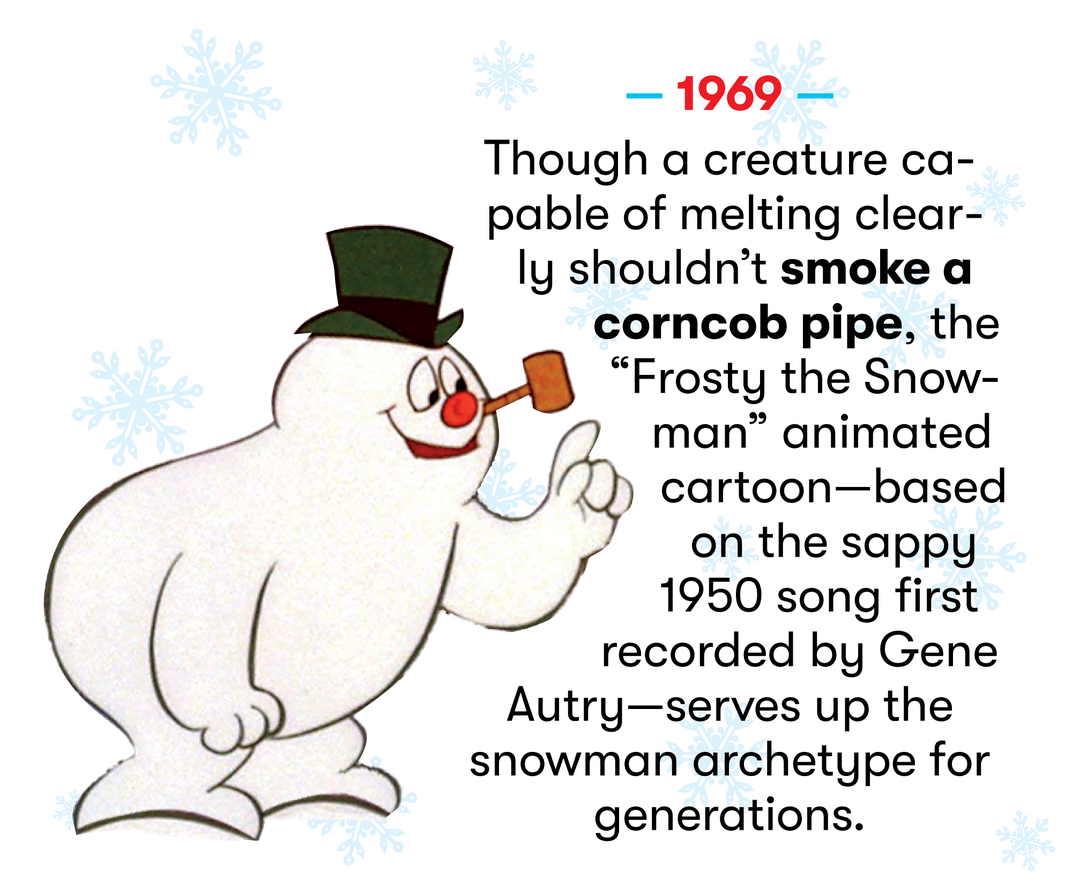

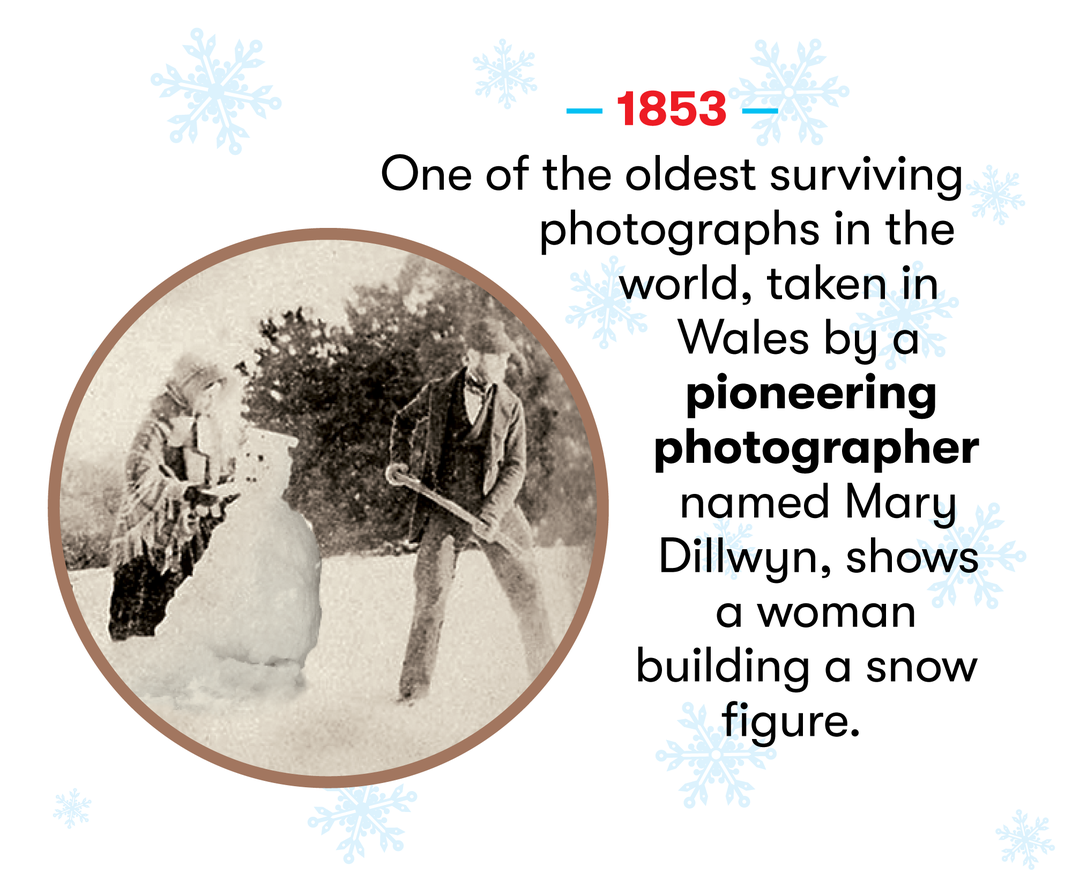

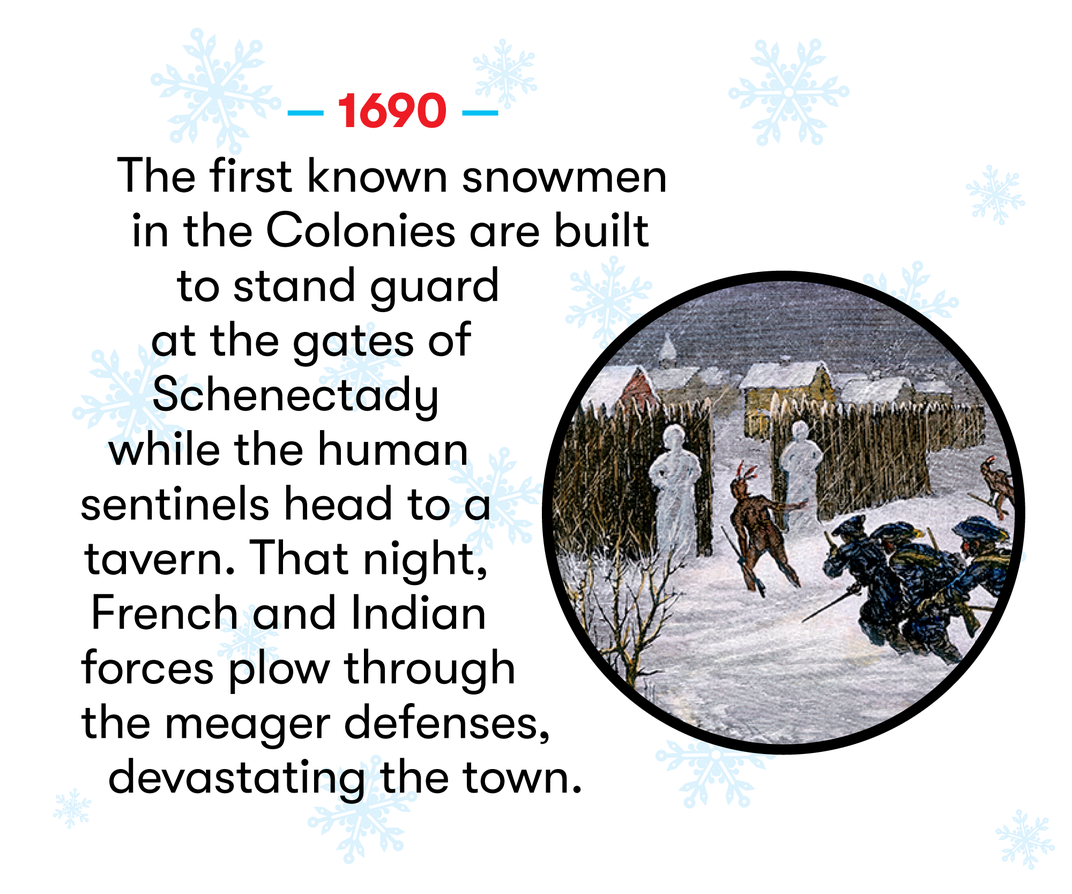

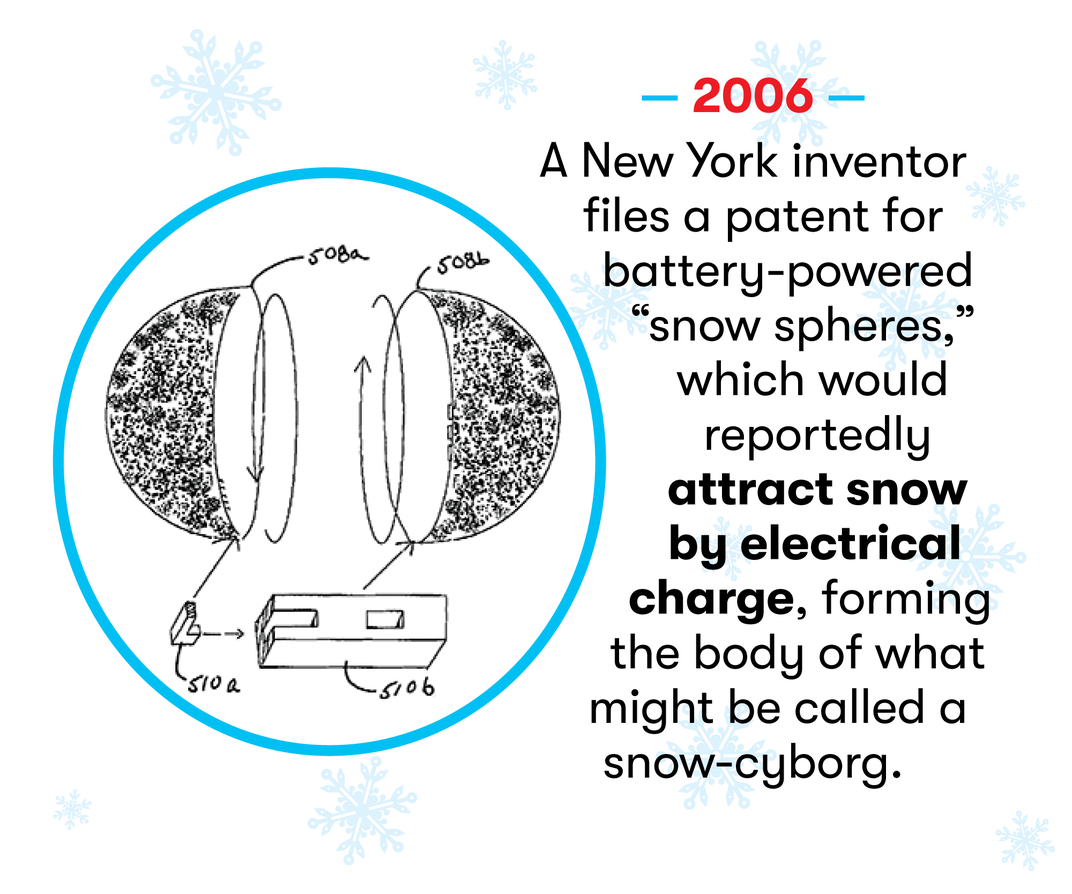

Bob Eckstein’s New Illustrated History of The Snowman digs out the surprisingly long tale of our frozen friend, from the Tao to Disney

The Illustrated History of the Snowman

A thoroughly entertaining exploration, this book travels back in time to shed light on the snowman's enigmatic past, from the present day to the Dark Ages.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/83/52/835249cc-b715-42bf-81ea-ef6dcba66ab7/2013.png)