When Tuberculosis Struck the World, Schools Went Outside

A century ago, a deadly disease sparked a novel concept: teaching in the great outdoors to keep kids safe

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b2/93/b293391c-b7a2-4352-bc6e-a0f3d75a4e09/openluchtschool_in_de_vrieskou_open-air_school_in_the_freezing_cold_3915530627_1.jpg)

In 1905, when tuberculosis plagued the United States, and Americans lived in deadly fear of the disease, a New York City health official addressed the American Academy of Medicine, pleading for changes at the nation’s schools. “To remove all possible causes which might render a child susceptible to the invasion of tuberculosis during school life, we must appeal to school boards, superintendents teachers, and school physicians to do all in their power.” Alarmed, the speaker noted that windows in American classrooms only opened halfway, and should be immediately replaced with French-style windows to “permit twice the amount of foul air to go out, and of good air to come in.” Every school must have a large playground, he continued, and classroom ventilation “of the most improved kind.” Schoolrooms were to be washed daily, and a “judicious curriculum” was to include “as much outdoor instruction as possible.”

The speaker was S. Adolphus Knopf, a German-born expert on tuberculosis and the founder of the National Tuberculosis Association, which became the American Lung Association. Like many leading minds of his generation, Knopf took an approach to science that was informed by the racist tenets of eugenics. For Knopf, slowing the spread of tuberculosis—an infectious disease second only to influenza in its deadliness—required investing in healthy, young bodies to prevent racial, national and even military decline. By 1915, Knopf argued that “open-air schools and as much open-air instruction as possible in kindergarten, school and college should be the rule.”

Today, as parents struggle with school closures and the prospect of many months of distance learning, some are asking why school can't be held outside, where transmission risk of Covid-19 is lower. There are currently no large-scale plans in the U.S. to move classrooms into the open, but it’s not for lack of precedent. In the early 20th century, when tuberculosis killed one in seven people in Europe and in the United States, outdoor schools proliferated, first in Germany and then around the world. Physicians and public health officials worried that overcrowded cities and cramped apartments were unnatural and unhealthy, given the lack of fresh air and sunlight, and that children—cooped up indoors for much of the day—were especially vulnerable to the ravages of tuberculosis. The solution was to move school outdoors, where children would “learn to love fresh air,” according to Knopf. There, “the tuberculous child” would not “be a danger to his comrades.”

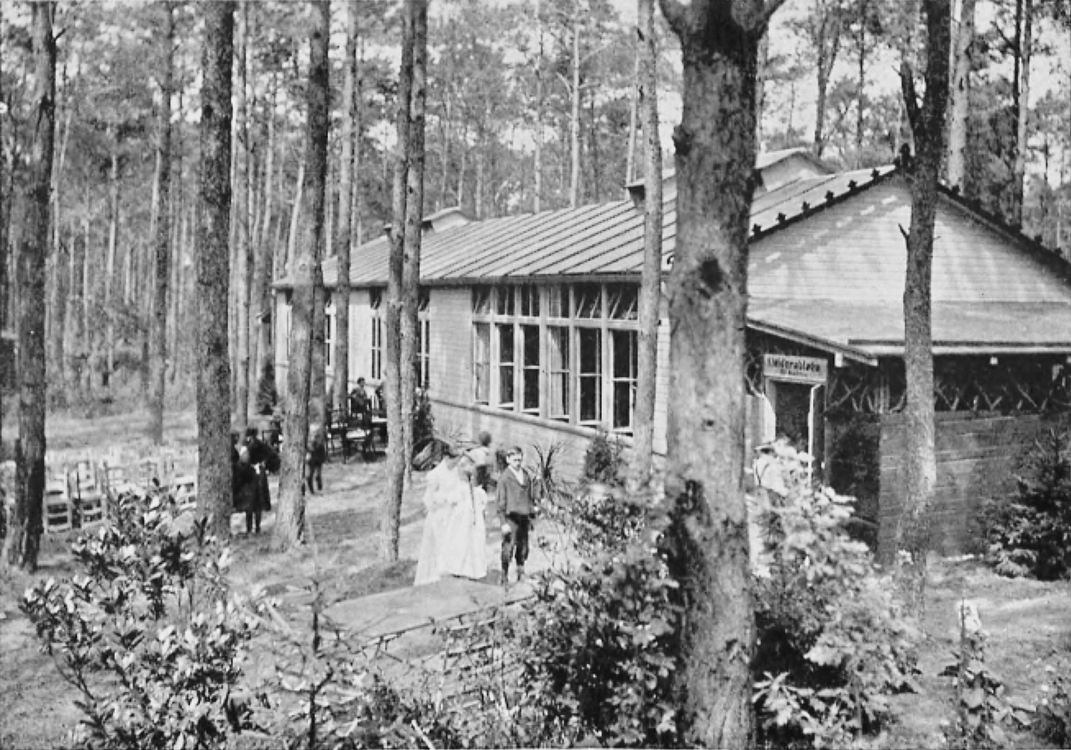

On August 1, 1904, the world’s first open-air school held lessons for the “delicate children of needy families” in a pine forest in Charlottenburg, a prosperous town near Berlin. The idea for a Waldschule, or forest school, came from Bernhard Bendix, a pediatrician at Berlin’s Charité Hospital, and Hermann Neufert, a local school inspector. The men worked with Adolf Gottstein, an epidemiologist and Charlottenburg’s chief medical officer, to plan the school and secure municipal funding. The state welcomed the idea. Tuberculosis threatened German society and its devastating effects turned child health into a national priority.

In 1904, Germany recorded a staggering 193.8 tuberculosis deaths for every 100,000 people. (For comparison’s sake, the United States is currently recording about 52 deaths for every 100,000 people during the Covid-19 pandemic.) According to public health experts, inadequate ventilation and poor hygiene were to blame: crowded tenements, stuffy rooms, dirty linens, bed-sharing in working-class families and too many sedentary hours spent indoors. “Both physicians and the public were very concerned about tuberculosis,” says Paul Weindling, the Wellcome Trust research professor in the history of medicine at England’s Oxford Brookes University. “There were many social distancing guidelines in diverse social contexts, as well as efforts to regulate personal behavior.”

Lacking medicines to treat the disease, let alone a vaccine, health professionals focused their energies on reforming personal behavior and the environment. Public placards and posters warned against spitting on the ground, a common practice. Health officials crusaded for fresh air and exercise, demanded reductions in housing density, and called for the construction of playgrounds and parks to serve as the “lungs” of the city. “Air, light, and space became the priorities of architects, municipal officials, and public health experts,” writes Weindling in his book Health, Race and Politics between German Unification and Nazism.

Child deaths from tuberculosis remained relatively rare, but German physician Robert Koch’s discovery of the tubercle bacillus in 1882 led to a “tuberculin test” that uncovered large numbers of infected children, even if they didn’t show symptoms. This finding was made even more troubling by another in 1903: Childhood tuberculosis infection could become latent or dormant, only to reactivate in adulthood, causing illness and death. In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech in 1905, Koch confirmed that tuberculosis was an airborne disease: “Even the smallest drops of mucus expelled into the air by the patient when he coughs, clears his throat, and even speaks, contain bacilli and can cause infection.” Koch’s words served as a call to action. Tuberculosis couldn’t be vanquished, but its spread could be contained in the streets, public places and schools.

On a plot designated by officials for the open-air school, builders installed a pavilion, gardens, activity areas and open sheds, some fitted with tables and benches for lessons. The school grounds also included a larger shed for meals, an enclosed shelter for rainy days and rest periods, a teacher’s room, a kitchen, toilets and a “cure gallery,” a special structure designed to maximize sun exposure. In a departure from prevailing norms and in keeping with the goals of progressive educators, boys and girls were never separated. Whereas the average school in Prussia—Germany’s largest and most populous state—counted two square meters per pupil, students at Charlottenburg’s forest school enjoyed 40.

The forest school in Charlottenburg isolated children who were “tuberculosis contacts,” at risk of catching the disease at home, or “anemic and undernourished,” a preexisting condition that was believed to raise the risk of infection. Bendix and Neufert targeted working-class city children who were shown in studies to be “tuberculized” at higher rates. Since 1899, when the International Congress on Tuberculosis met in Berlin and discussed, among other things, the plight of workers, public health experts worried that the chain of contagion would never be broken without access to “open air” at home or at a sanatorium, the spa-like retreat for those who could afford it. The forest school ensured a steady supply of fresh air to the children of workers. Half the school’s teachers were former patients at sanatoria, where they had already recovered from tuberculosis.

The small school was soon swamped with so many applicants that it expanded to accommodate 250 students. What began as a local experiment attracted dozens of foreign visitors in just a few months and became an international sensation. By 1908, open-air schools were up and running in Britain, France, Belgium, Switzerland, Spain and Italy. That same year, the first outdoor school opened in the United States, in Providence, Rhode Island, in the dead of winter no less. The work of two women doctors—Mary Packard, the first woman graduate of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, and Ellen Stone, the founder of Providence’s League for the Suppression of Tuberculosis—the Providence Open-Air School was housed in an old school building, where a brick wall had been removed and replaced with large windows that always remained open. To protect the school’s 25 “delicate children” from the cold, wool mittens, hats, overshoes and “sitting-out bags,” the equivalent of today’s sleeping bags, were provided. Between 1910 and 1925, hundreds of outdoor schools “rooted in different cultural contexts,” while hewing to the German model, opened around the world, according to Anne-Marie Châtelet, a historian of architecture at the University of Strasbourg.

On the eve of World War I, the U.S. counted some 150 open-air institutions in 86 cities. Behind every outdoor school was an anti-tuberculosis association that included physicians and laypeople. These voluntary groups were a diffuse but growing presence in American life—there were 20 anti-tuberculosis associations in 1905 and 1,500 in 1920. Scholars have attributed a number of the strategies deployed in modern public health campaigns to their efforts.

As with many things education-related, the founders of the Providence school looked to Germany. Since the 1840s, when Horace Mann, then secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Education, traveled to Prussia to report on the world’s first free and compulsory schools, generations of American educators flocked to the German lands to study everything from curriculum and instruction to school architecture and classroom ventilation. The open-air school was no exception.

Open-air schools in Boston, New York, Chicago, Hartford, Rochester and Pittsburgh followed, each shepherded into existence by a local anti-tuberculosis group. Unlike the Waldschule and its counterparts found in parks on the outskirts of European cities, these schools were located in dense urban areas. For American educators scrambling to meet the challenges of skyrocketing enrollments—the result of rapid urbanization, immigration and the enforcement of compulsory schooling laws—the outdoor schools promised some relief. At least it would remove at-risk children “from what many health experts considered the overheated and noxious atmosphere of the typical school room,” writes Richard Meckel, a professor of American Studies at Brown University, in an article on the early history of the schools, “and provide them with sustained exposure to cold air, which was widely believed to promote strength and vigor by stimulating the appetite and increasing respiratory and vascular activity.” It was this line of thinking that drew support from the eugenics movement. “Eugenicists prioritized the wider society and future generations,” says Weindling, “and many thought that promoting fitness could prevent infections, which justified open-air schools.”

On both sides of the Atlantic, health experts viewed the city as a breeding ground for disease, where tuberculosis would continue its deadly rampage if conditions for workers and their families weren’t ameliorated. Open-air prophylaxis was available to paying clients at a sanatorium, but not the families of workers or the poor. Today, as public health experts emphasize the importance of ventilation and outside air, concerns over essential workers who face the highest risk of exposure to Covid-19, are back.

So, too, is interest in outdoor schools. According to recent reporting, more than 250 “nature-based preschools and kindergartens” are operating in the U.S., most of them barely a decade old. The Natural Start Alliance was created in 2013 to address “dramatic growth in nature-based early childhood education,” and a national survey conducted in 2017 found that eight out of 10 programs had started a waitlist in the previous 12 months. Like early 20th-century fears that city children were dangerously disconnected from nature, today’s worry is that screen time has eclipsed outdoor play.

And while the open-air schools of a century ago were conceived for the families of workers—for the purposes of public health and nationalist ideals—outdoor schools and outdoor learning pods, now cropping up across the country, cater to a different demographic. “Nature schools in the United States tend to be filled with white, upper class kids,” the Oregon Association for the Education of Young Children observed in 2018. Change is unlikely, since the shuttering of schools has only accelerated gaps in educational opportunity.

As more white Americans reckon with a long history of racial injustice, it’s worth acknowledging that these open-air schools were a product of their time, with its hierarchies of race and class permeating ideas about public health and the nation. Just as the modern pandemic has laid bare the inequities of the health care system, so too could a return to mass outdoor schooling, where proper supplies must be secured, warm clothing worn and wide open spaces made available.

After World War II, new antibiotics dispelled the deadliness of tuberculosis, and open-air schools faded into irrelevance. Today their history is a reminder of what was once possible, as others have noted. But that only came to fruition when Americans were willing to look abroad for new ideas and when the nation viewed its own health and vitality as inextricably bound up with its schools.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Daniela_Blei_portrait.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Daniela_Blei_portrait.jpg)